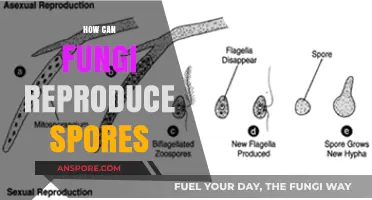

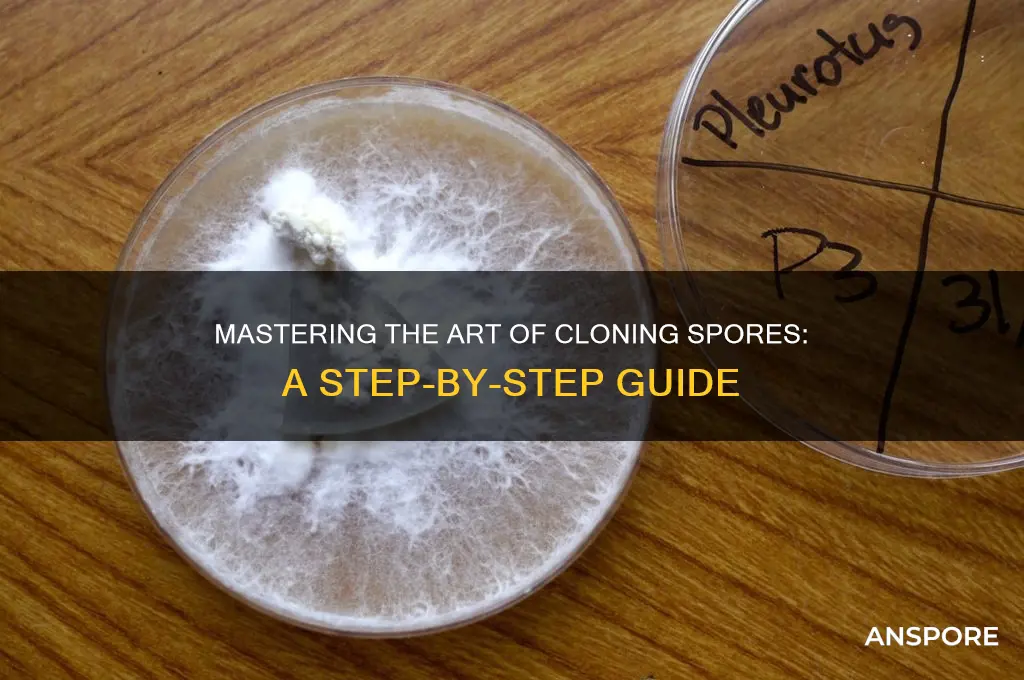

Cloning spores is a fascinating process that involves isolating and replicating individual fungal or bacterial spores to create genetically identical copies. This technique is widely used in microbiology, agriculture, and biotechnology for purposes such as preserving beneficial strains, studying genetic traits, or producing consistent cultures for research and industrial applications. The process typically begins with sterilizing the spore source to prevent contamination, followed by carefully transferring a single spore to a nutrient-rich medium under controlled conditions. As the spore germinates and grows, it can be subcultured or propagated to generate multiple clones, ensuring uniformity and purity in the resulting population. Understanding the methods and best practices for cloning spores is essential for anyone working with microorganisms, as it allows for precise control over genetic material and experimental outcomes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Method | Spores can be cloned through asexual reproduction methods such as spore isolation, sterilization, and cultivation on nutrient-rich media. |

| Spores Types | Fungal spores (e.g., mushrooms), bacterial spores (e.g., Bacillus), and plant spores (e.g., ferns) can be cloned. |

| Isolation | Spores are collected from mature fruiting bodies or spore-bearing structures, then suspended in sterile water or buffer. |

| Sterilization | Surface sterilization using dilute bleach or ethanol to remove contaminants without harming spores. |

| Cultivation | Spores are plated on agar media (e.g., PDA for fungi) and incubated under optimal conditions (temperature, humidity, light). |

| Germination | Spores germinate into mycelium (fungi) or colonies (bacteria) after 3–14 days, depending on the species. |

| Cloning | Individual colonies or mycelium are subcultured to ensure genetic uniformity, creating clones of the original spore. |

| Storage | Cloned spores can be stored long-term in glycerol stocks (bacteria) or as dried spore prints (fungi). |

| Applications | Used in mushroom cultivation, biotechnology, research, and preservation of endangered species. |

| Challenges | Contamination risk, species-specific requirements, and maintaining genetic stability during cloning. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Conditions: Optimal temperature, humidity, and light for spore production

- Isolation Techniques: Methods to separate spores from parent organisms

- Sterilization Methods: Preventing contamination during spore cloning

- Germination Process: Activating spores for successful cloning

- Storage Solutions: Preserving spores for long-term cloning viability

Sporulation Conditions: Optimal temperature, humidity, and light for spore production

Spores, the resilient reproductive units of fungi, require precise environmental conditions to initiate sporulation. Temperature plays a pivotal role, with most species favoring a range between 20°C and 28°C (68°F to 82°F). For example, *Aspergillus niger*, a common mold, achieves peak spore production at 25°C (77°F). Deviations from this range can either delay sporulation or halt it entirely. Cold temperatures below 15°C (59°F) often inhibit spore formation, while heat above 35°C (95°F) can denature essential enzymes, rendering the process inefficient.

Humidity is equally critical, as spores require moisture to develop and mature. Relative humidity levels between 70% and 90% are ideal for most fungi. *Penicillium* species, for instance, thrive at 85% humidity, where water vapor in the air facilitates the growth of hyphae and subsequent spore release. However, excessive humidity (above 95%) can lead to waterlogging, promoting bacterial contamination or fungal rot. Conversely, humidity below 60% desiccates the substrate, stalling sporulation. Maintaining consistent moisture through misting or humidifiers is essential for optimal results.

Light exposure, often overlooked, significantly influences sporulation in certain fungi. While many species are indifferent to light, others, like *Neurospora crassa*, require specific light wavelengths to trigger spore production. Blue light (450–495 nm) has been shown to stimulate sporulation in this fungus, with exposure durations of 12–16 hours daily yielding the best results. In contrast, constant darkness may inhibit sporulation in light-sensitive species. For home cultivators, LED grow lights with adjustable spectra can mimic natural conditions, ensuring precise control over this variable.

Practical implementation of these conditions requires careful monitoring and adjustment. Use thermometers and hygrometers to track temperature and humidity, and invest in a programmable timer for light control. For small-scale projects, a humidity-controlled chamber lined with damp paper towels can suffice, while larger operations may require environmental chambers with integrated sensors. Regularly inspect the substrate for signs of contamination, as even minor deviations from optimal conditions can compromise spore viability. By mastering these variables, cultivators can maximize spore yield and ensure consistent results across batches.

Buying Psychedelic Spores in Ireland: Legalities and Availability Explained

You may want to see also

Isolation Techniques: Methods to separate spores from parent organisms

Spores, by design, are resilient and often tightly integrated with their parent organisms, making isolation a delicate yet crucial step in cloning. Effective separation ensures purity and viability, laying the groundwork for successful replication. Here’s how to approach this critical phase with precision.

Mechanical Disruption: Breaking the Bond

One of the most direct methods involves physically separating spores from their parent structure. For fungi like *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, gently grinding sporulating cultures in a sterile mortar and pestle with a small volume of sterile water or buffer can release spores. Filamentous molds often require agitation in a sterile saline-Tween solution (0.05% Tween 80) to reduce surface tension and dislodge spores without damaging them. For plant spores, such as ferns or mosses, a soft brush or air puff over the sporangia can effectively collect spores without contaminating them with vegetative tissue. Always filter the suspension through a fine mesh (e.g., 40–60 μm) to remove larger debris before proceeding.

Chemical Treatment: Targeted Release

Chemical agents can facilitate spore isolation by weakening the attachment to the parent organism. For bacterial endospores, such as *Bacillus* spp., heating a culture suspension to 80°C for 10–15 minutes kills vegetative cells while leaving spores intact. In plants, enzymes like pectinase or cellulase can be applied to degrade cell walls surrounding spore-bearing structures, freeing spores for collection. For example, treating *Marchantia* (liverwort) thalli with 2% cellulase in a phosphate buffer (pH 5.5) at 37°C for 2 hours effectively releases gemmae (asexual spores) without compromising viability. Always neutralize or wash away chemicals post-treatment to avoid inhibiting spore germination.

Density-Based Separation: Leveraging Buoyancy

Spores often differ in density from parent tissues, allowing for separation via centrifugation or flotation. A common technique involves layering a spore suspension onto a density gradient medium, such as sucrose or Percoll. For instance, fungal spores typically have a density of 1.1–1.3 g/cm³, while mycelial fragments are denser. Centrifuging at 500–1000g for 10 minutes causes spores to band at the interface, where they can be carefully aspirated. Alternatively, a simple water flotation method works for plant spores, as they are often lighter than degraded tissue remnants. This approach is particularly useful for isolating spores from contaminated samples, ensuring a cleaner starting material for cloning.

Selective Filtration: Precision in Purity

Filtration is a cornerstone of spore isolation, especially when dealing with microorganisms. A 5–8 μm pore size filter effectively retains most fungal hyphae and bacterial cells while allowing spores (typically 1–5 μm) to pass through. For larger plant spores, such as those of *Polypodium* ferns (10–20 μm), a 30 μm filter can be used. Pairing filtration with vacuum or positive pressure systems speeds up the process, but caution is needed to avoid damaging spores. Post-filtration, spores can be concentrated by centrifugation at low speeds (e.g., 500g for 5 minutes) and resuspended in a minimal volume of sterile medium for cloning.

Cautions and Considerations: Preserving Viability

While isolating spores, maintaining their viability is paramount. Avoid harsh chemicals or excessive mechanical force that could rupture spore coats. Always work under sterile conditions to prevent contamination, especially when dealing with microorganisms. For long-term storage, spores can be suspended in 15–20% glycerol and frozen at -80°C, though some species may require specific desiccation protocols. Regularly assess spore viability post-isolation using tetrazolium chloride staining or germination assays to ensure cloning efforts are not in vain. With careful technique, isolated spores become a reliable foundation for cloning, unlocking their genetic potential for research, agriculture, or biotechnology.

Where to Buy Truffle Spores for Successful Cultivation at Home

You may want to see also

Sterilization Methods: Preventing contamination during spore cloning

Contamination is the arch-nemesis of successful spore cloning, capable of derailing weeks of effort in a matter of days. Sterilization methods are your first and most critical line of defense. Every surface, tool, and medium must be treated as a potential vector for unwanted microbes. Autoclaving, a process using steam under pressure (121°C for 15-20 minutes), is the gold standard for sterilizing equipment and growth media. For heat-sensitive materials, chemical sterilization with 70% ethanol or 10% bleach solutions can be effective, but these must be followed by thorough rinsing to avoid residue that could harm spores.

Consider the environment itself—your workspace is a silent culprit in contamination. HEPA filters in laminar flow hoods create a sterile air stream, essential for handling spores openly. UV-C light (254 nm wavelength) can sterilize surfaces pre-use, but it’s ineffective in the presence of organic matter, so cleanliness must precede its application. Even personal protective equipment (PPE) like gloves and lab coats requires attention; gloves should be sterilized with ethanol before touching critical areas, and lab coats must be changed frequently to minimize particulate transfer.

A less obvious but equally critical aspect is the sterilization of water used in cloning processes. Distillation or reverse osmosis removes impurities, but subsequent autoclaving is necessary to eliminate any surviving microorganisms. For agar plates, adding antibiotics like streptomycin (50 µg/mL) or ampicillin (100 µg/mL) can provide a secondary safeguard against bacterial contamination, though this must be balanced against potential toxicity to the spores themselves.

Finally, the timing and consistency of sterilization protocols cannot be overstated. Spores are resilient, but the cloning process often requires their activation, making them temporarily vulnerable. A single oversight—a missed corner during surface disinfection, an under-autoclaved tool, or an unfiltered air supply—can introduce contaminants that thrive at the expense of your spores. Rigorous adherence to sterilization methods isn’t just a step; it’s the foundation of reliable spore cloning.

Bacterial Spores: Their Role in Reproduction and Survival Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Germination Process: Activating spores for successful cloning

Spores, with their remarkable resilience, remain dormant until conditions trigger germination—a critical step in cloning. This process involves breaking the spore’s dormancy and initiating growth, a delicate balance of hydration, temperature, and nutrient availability. Without proper activation, spores remain inert, rendering cloning attempts futile. Understanding the germination process is thus foundational for anyone seeking to clone spores successfully.

Analytical Insight:

Spores enter dormancy as a survival mechanism, encased in a protective coat that resists harsh environments. Germination begins when water penetrates this coat, rehydrating the spore and reactivating metabolic processes. This hydration phase is followed by the emergence of a germ tube, the first visible sign of growth. However, not all spores germinate uniformly; factors like species, age, and storage conditions influence success rates. For instance, older spores may require scarification—a process of physically weakening the spore coat—to enhance water uptake. Research shows that spores stored at -20°C retain viability for decades, but improper storage reduces germination efficiency by up to 40%.

Instructive Steps:

To activate spores for cloning, start by sterilizing your workspace and equipment to prevent contamination. Place spores in a sterile solution of distilled water or nutrient broth, ensuring a concentration of 10^6 spores per mL for optimal results. Incubate at 25–30°C, maintaining humidity levels above 90% to mimic natural conditions. For recalcitrant spores, apply a 10-minute heat shock at 50°C or treat with 1% hydrogen peroxide for 30 minutes to weaken the spore coat. Monitor for germ tube formation within 24–48 hours, indicating successful activation. Once germinated, transfer spores to a growth medium like agar plates supplemented with 2% glucose and 0.5% yeast extract to support further development.

Comparative Perspective:

Unlike seed germination, spore activation relies less on light and more on chemical cues. While seeds often require specific light wavelengths to break dormancy, spores respond primarily to water, nutrients, and temperature. Additionally, spores lack the embryonic structures of seeds, necessitating a different approach to cloning. For example, fungi spores thrive in media with a pH of 5.5–6.0, whereas plant spores may require a slightly alkaline environment. Understanding these differences ensures tailored activation strategies, maximizing cloning success across species.

Practical Tips:

For hobbyists, investing in a humidifier or using sealed containers with damp paper towels can maintain the high humidity needed for germination. Avoid over-crowding spores on growth plates, as competition for resources can hinder development. If using chemical treatments, always test a small sample first to avoid damaging spores. Finally, document each step, including incubation times and environmental conditions, to refine your process over time. With patience and precision, activating spores becomes a repeatable science, paving the way for successful cloning.

Can Fungi Develop Spores on Living Hosts? Exploring Symbiotic Possibilities

You may want to see also

Storage Solutions: Preserving spores for long-term cloning viability

Spores, with their remarkable resilience, can survive harsh conditions, but preserving them for long-term cloning viability requires careful storage solutions. Desiccation, or complete dehydration, is a proven method for extending spore lifespan. Spores stored at room temperature in airtight containers with desiccants like silica gel can remain viable for decades. However, extreme temperatures and humidity fluctuations must be avoided, as they can compromise spore integrity. For optimal results, store desiccated spores in a cool, dark place, maintaining a consistent temperature between 4°C and 25°C.

An alternative storage method involves cryopreservation, which offers even greater longevity. This technique requires suspending spores in a cryoprotectant solution, such as 10% skim milk or glycerol, before freezing them in liquid nitrogen (-196°C). While effective, cryopreservation demands specialized equipment and handling to prevent cellular damage during freezing and thawing. Researchers often use controlled-rate freezers to minimize ice crystal formation, ensuring spore viability upon revival. This method is particularly valuable for preserving rare or endangered fungal species.

For hobbyists and small-scale cultivators, a simpler yet effective approach is vacuum-sealed storage. Spores can be placed on sterile filter paper or in glass vials, then vacuum-sealed to remove oxygen and moisture. This method significantly slows metabolic activity and reduces the risk of contamination. Adding a desiccant packet to the vacuum bag provides an extra layer of protection. Stored in a refrigerator (2°C–8°C), vacuum-sealed spores can retain viability for up to 10 years, making this an accessible and cost-effective solution.

Comparing these methods reveals trade-offs between convenience and longevity. Desiccation is straightforward but requires vigilant environmental control, while cryopreservation offers unparalleled durability at the cost of complexity. Vacuum-sealed storage strikes a balance, providing moderate long-term viability with minimal technical requirements. The choice depends on the scale of operation, available resources, and the intended duration of storage. Regardless of the method, regular viability testing is essential to ensure spores remain clonable over time.

In practice, combining these techniques can maximize preservation success. For instance, desiccated spores can be further protected by storing them in vacuum-sealed containers, especially in humid climates. Labeling storage vessels with collection dates, species information, and storage conditions is critical for tracking and future use. By understanding and implementing these storage solutions, enthusiasts and researchers alike can safeguard spores for long-term cloning, ensuring genetic diversity and experimental reproducibility.

Do Rhizopus Spores Have Flagella? Unraveling the Fungal Mobility Mystery

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Cloning spores allows for the propagation of a specific fungal strain with desirable traits, ensuring genetic consistency and purity for research, agriculture, or industrial applications.

Basic equipment includes a sterile workspace, microscope, scalpel or needle, agar plates with growth medium, and a sterile container for spore collection.

Using a sterile needle or scalpel under a microscope, carefully pick a single spore from the source and transfer it to a sterile agar plate to initiate growth.

A nutrient-rich medium like Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) or Malt Extract Agar (MEA) is commonly used, as it supports spore germination and mycelial growth.

Depending on the fungal species, it typically takes 3–14 days for a single spore to germinate and develop into a visible colony on an agar plate.