Fungi are remarkable organisms with diverse reproductive strategies, and one of their most fascinating methods involves the production and dispersal of spores. These microscopic structures serve as the primary means of reproduction for many fungal species, allowing them to propagate and colonize new environments. Fungi can reproduce spores through both sexual and asexual processes, depending on the species and environmental conditions. Asexual reproduction often involves the formation of structures like conidia or sporangiospores, which are released into the air or water, enabling rapid colonization. Sexual reproduction, on the other hand, typically requires the fusion of compatible hyphae, leading to the development of specialized structures such as asci or basidia, which produce and release spores. Understanding how fungi reproduce spores is crucial for fields like ecology, agriculture, and medicine, as it sheds light on their role in ecosystems, their impact on plant and human health, and their potential applications in biotechnology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Methods | Sexual and Asexual |

| Sexual Reproduction | Involves the fusion of haploid cells (gametes) from two compatible individuals, resulting in the formation of a diploid zygote. The zygote then undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores (e.g., asci spores in Ascomycetes, basidiospores in Basidiomycetes). |

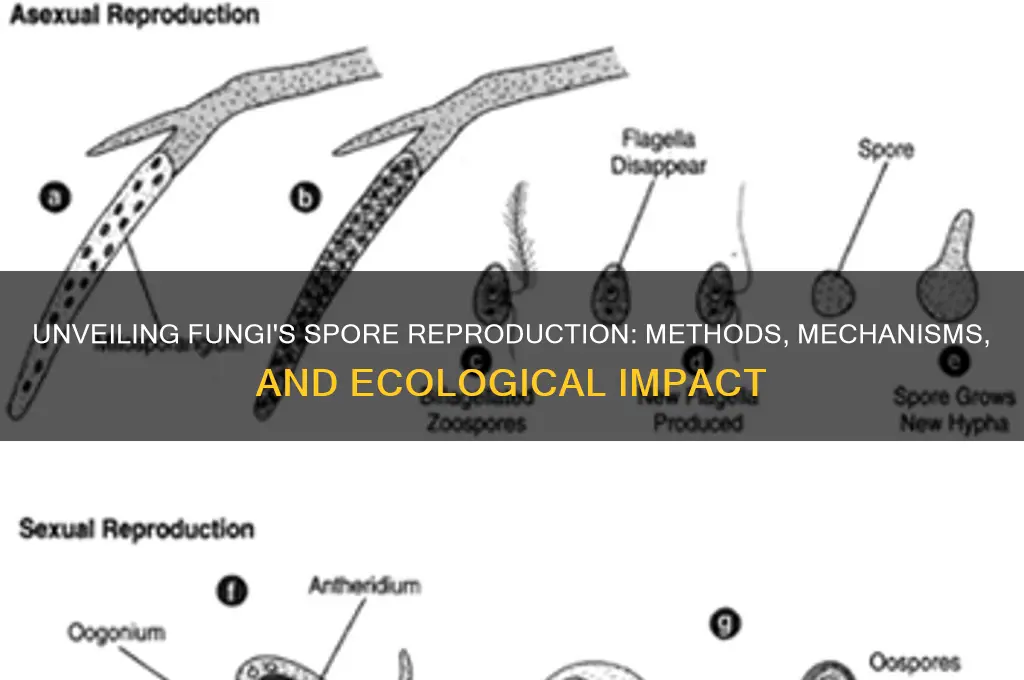

| Asexual Reproduction | Occurs via vegetative spores (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores, zoospores) produced by mitosis, without the need for gamete fusion. |

| Spore Types | Conidia, Sporangiospores, Zoospores, Ascospores, Basidiospores, Oospores |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Wind, Water, Animals, Insects, Human Activities |

| Spore Production Structures | Conidiophores, Sporangia, Ascocarps, Basidiocarps, Oogonia |

| Environmental Triggers | Nutrient Availability, Light, Temperature, Humidity, pH |

| Spore Dormancy | Many spores can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh conditions until favorable environments trigger germination. |

| Germination Requirements | Water, Suitable Temperature, Nutrients, Oxygen |

| Ecological Role | Spores aid in survival, dispersal, and colonization of new habitats, contributing to fungi's role in ecosystems as decomposers, symbionts, and pathogens. |

| Human Impact | Fungal spores can cause allergies, diseases, and food spoilage but are also used in biotechnology, agriculture, and medicine (e.g., antibiotics, enzymes). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Asexual Sporulation: Fungi produce spores like conidia via mitosis, allowing rapid reproduction without mating

- Sexual Sporulation: Fungi form spores (e.g., asci, basidia) through meiosis after mating

- Sporangiospores: Spores develop inside sporangia and are released through rupture or active discharge

- Budding Yeasts: Yeasts reproduce asexually by budding, forming new cells from parent cells

- Environmental Triggers: Sporulation is influenced by factors like nutrient scarcity, light, and humidity

Asexual Sporulation: Fungi produce spores like conidia via mitosis, allowing rapid reproduction without mating

Fungi have mastered the art of survival through diverse reproductive strategies, and asexual sporulation stands out as a remarkably efficient method. Unlike sexual reproduction, which requires mating and genetic recombination, asexual sporulation involves the production of spores like conidia through mitosis—a process that duplicates the parent cell's genetic material without variation. This mechanism allows fungi to reproduce rapidly, colonize new environments, and respond swiftly to favorable conditions. For instance, *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* species are well-known for their ability to produce conidia in vast quantities, enabling them to thrive in diverse habitats, from soil to decaying matter.

To understand the practical implications, consider the steps involved in asexual sporulation. First, the fungus develops specialized structures called conidiophores, which serve as the foundation for spore production. Next, conidia form at the tips or sides of these structures through mitotic divisions. These spores are then released into the environment, often aided by wind, water, or physical disturbances. The simplicity of this process—requiring only a single parent and minimal energy—makes it an ideal strategy for fungi to expand their populations quickly. For example, a single *Fusarium* species can produce millions of conidia within days under optimal conditions, ensuring its survival even in competitive ecosystems.

While asexual sporulation offers speed and efficiency, it comes with limitations. The lack of genetic diversity in offspring can make fungal populations vulnerable to environmental changes or diseases. However, this trade-off is often justified in stable environments where rapid colonization is key. Gardeners and farmers, for instance, can observe this phenomenon when mold spreads quickly on damp surfaces or when powdery mildew infects crops. Understanding this process allows for targeted interventions, such as improving air circulation or using fungicides to disrupt spore dispersal.

From a comparative perspective, asexual sporulation contrasts sharply with sexual reproduction in fungi. While sexual spores (like asci or basidiospores) are genetically diverse and better equipped for long-term survival, conidia are the workhorses of rapid proliferation. This distinction highlights the adaptability of fungi, which can switch between strategies based on environmental cues. For researchers and enthusiasts, studying these differences provides insights into fungal ecology and potential applications in biotechnology, such as using conidia for biological pest control or enzyme production.

In practical terms, managing asexual sporulation in fungi requires a proactive approach. For indoor environments, maintaining low humidity levels (below 60%) and proper ventilation can inhibit spore production. In agriculture, crop rotation and resistant plant varieties reduce the risk of fungal infections. Interestingly, some fungi, like *Trichoderma*, are harnessed as biocontrol agents because their rapid asexual reproduction helps them outcompete pathogenic fungi. By leveraging this knowledge, individuals can mitigate the negative impacts of fungal spores while appreciating their ecological significance.

Holmes Tower Air Purifier: Does VisiPure Kill Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Sexual Sporulation: Fungi form spores (e.g., asci, basidia) through meiosis after mating

Fungi, unlike plants and animals, have evolved unique reproductive strategies centered around spore formation. One of the most intricate methods is sexual sporulation, where fungi produce specialized spores like asci and basidia through the process of meiosis following mating. This mechanism ensures genetic diversity, a critical factor for fungal survival and adaptation in diverse environments.

Consider the life cycle of ascomycetes, fungi that produce spores within sac-like structures called asci. After compatible hyphae (filaments) from two individuals fuse, a dikaryotic phase begins, where two haploid nuclei coexist in a single cell. Meiosis then occurs within the ascus, resulting in the formation of eight haploid ascospores. These spores are released into the environment, where they can germinate and grow into new individuals. For example, the yeast *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast) undergoes a similar process, though its asci are often contained within a fruiting body called an ascocarp.

In contrast, basidiomycetes produce spores on club-shaped structures called basidia. After mating, a dikaryotic mycelium develops, and basidia form at the tips of specialized hyphae. Meiosis within the basidium yields four haploid basidiospores, which are often ejected forcefully to disperse over distances. The mushroom *Agaricus bisporus* (button mushroom) is a classic example, where basidiospores are produced under the cap and released into the air. This method of spore ejection, known as ballistospore discharge, can propel spores up to 10 millimeters, enhancing their dispersal range.

The key advantage of sexual sporulation lies in its ability to generate genetic variation. By shuffling genetic material through meiosis and fertilization, fungi can adapt to changing conditions, resist pathogens, and exploit new ecological niches. For instance, in agricultural settings, understanding this process is crucial for managing fungal diseases. Fungicides targeting mating or meiosis can disrupt spore formation, reducing the spread of pathogens like *Magnaporthe oryzae*, which causes rice blast.

Practical applications of this knowledge extend beyond agriculture. In biotechnology, fungi like *Aspergillus niger* are engineered to produce enzymes and metabolites through controlled sporulation. Researchers manipulate mating-type genes to induce sexual reproduction, optimizing spore yield and genetic diversity. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms, ensuring proper substrate conditions and humidity levels can encourage basidiocarp (mushroom) formation, leading to successful basidiospore production.

In summary, sexual sporulation in fungi is a sophisticated process that combines mating, meiosis, and spore formation to ensure genetic diversity and survival. Whether in the wild, the lab, or the garden, understanding this mechanism provides valuable insights into fungal biology and its practical applications.

Is Spore Still Functional? Troubleshooting Tips for Modern Systems

You may want to see also

Sporangiospores: Spores develop inside sporangia and are released through rupture or active discharge

Fungi employ a diverse array of strategies to reproduce, and one of the most fascinating methods involves sporangiospores. These spores develop within specialized structures called sporangia, which act as protective chambers during their maturation. Once the spores are ready, they are released through either the rupture of the sporangium or an active discharge mechanism. This process ensures efficient dispersal, allowing fungi to colonize new environments and survive adverse conditions. Understanding sporangiospores is crucial for fields like mycology, agriculture, and medicine, as it sheds light on fungal life cycles and their ecological roles.

Consider the zygomycetes, a group of fungi that exemplify sporangiospore production. In species like *Rhizopus stolonifer* (the black bread mold), sporangia form at the tips of erect structures called sporangiophores. Inside these sac-like structures, spores develop in multinucleate cells through mitosis. When mature, the sporangium wall either ruptures passively or actively discharges the spores, often aided by environmental factors like air currents or physical disturbance. This method maximizes dispersal efficiency, ensuring that spores reach new substrates where they can germinate and grow. For instance, a single sporangium of *Rhizopus* can release up to 100,000 spores, highlighting the reproductive potential of this strategy.

From a practical standpoint, understanding sporangiospore release is essential for controlling fungal growth in various settings. In agriculture, for example, knowing that sporangia can rupture upon physical contact (e.g., handling infected plants) helps in implementing preventive measures like wearing gloves or using sterile tools. Similarly, in indoor environments, reducing air movement can minimize spore dispersal from molds like *Mucor*. For researchers, studying the mechanics of active discharge—such as the explosive release seen in some species—offers insights into fungal adaptations and potential biotechnological applications, like developing spore-based delivery systems.

Comparatively, sporangiospores differ from other fungal spore types, such as conidia or ascospores, in their development and release mechanisms. While conidia form externally on specialized hyphae, sporangiospores are enclosed within sporangia, providing added protection during maturation. This distinction influences their resilience and dispersal strategies. For instance, sporangiospores of *Phycomyces* can survive desiccation and extreme temperatures, making them well-suited for harsh environments. In contrast, ascospores, produced within asci, are often released through a more controlled mechanism, reflecting their role in sexual reproduction.

In conclusion, sporangiospores represent a remarkable adaptation in fungal reproduction, combining protection and efficient dispersal. Whether through passive rupture or active discharge, this mechanism ensures that fungi can thrive in diverse ecosystems. By studying sporangiospores, we gain not only a deeper appreciation of fungal biology but also practical tools for managing fungal growth in agriculture, medicine, and beyond. For anyone working with fungi, recognizing the role of sporangia and their spores is a key step toward harnessing or controlling these microscopic powerhouses.

Customizing Spores in Civilization Age: Possibilities and Limitations Explored

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Budding Yeasts: Yeasts reproduce asexually by budding, forming new cells from parent cells

Fungi exhibit a remarkable diversity in reproductive strategies, but one of the most fascinating methods is the asexual reproduction of yeasts through budding. This process, where a new cell emerges as an outgrowth from the parent cell, is both efficient and adaptable, allowing yeasts to thrive in various environments. Unlike spore formation, which is common in many fungi, budding in yeasts is a direct and continuous mechanism that ensures rapid population growth under favorable conditions.

To understand budding, imagine a small, balloon-like protrusion forming on the surface of a yeast cell. This protrusion, called a bud, gradually increases in size as it receives nuclear material and cytoplasm from the parent cell. Over time, the bud matures, developing its own cell wall and organelles, until it eventually separates from the parent cell to become a new, independent organism. This process can repeat multiple times, with some yeast species capable of producing several buds in succession. For instance, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, commonly known as baker’s yeast, can complete budding within 90 to 120 minutes under optimal conditions, such as a nutrient-rich medium at 30°C.

From a practical standpoint, understanding yeast budding is crucial for industries like baking, brewing, and biotechnology. In baking, the rapid reproduction of yeast through budding is essential for dough fermentation, as it produces carbon dioxide gas that causes the dough to rise. Brewers similarly rely on yeast budding to ferment sugars into alcohol. To optimize budding in these applications, maintaining the right temperature (typically 25°C to 35°C) and nutrient availability (e.g., sugars and nitrogen sources) is key. For home brewers or bakers, monitoring these conditions can significantly improve the efficiency of yeast activity.

Comparatively, budding stands out from other fungal reproductive methods due to its simplicity and speed. While spore formation often requires specific environmental triggers and can be energy-intensive, budding occurs continuously as long as resources are available. This makes yeasts particularly resilient in stable environments, such as laboratory cultures or industrial fermenters. However, budding’s reliance on favorable conditions also means that yeasts are less equipped to survive harsh environments compared to spore-forming fungi, which can remain dormant for extended periods.

In conclusion, budding in yeasts is a testament to the ingenuity of fungal reproduction. Its direct, asexual nature allows for rapid proliferation, making yeasts indispensable in various industries. By mastering the conditions that promote budding, practitioners can harness the full potential of these microorganisms. Whether you’re a scientist, brewer, or baker, understanding this process not only deepens your appreciation for fungi but also enhances your ability to work with them effectively.

Understanding Spores: Mitosis or Meiosis Production Explained

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers: Sporulation is influenced by factors like nutrient scarcity, light, and humidity

Fungi, like all living organisms, have evolved strategies to ensure their survival and propagation, and sporulation is a key reproductive mechanism. However, this process is not spontaneous but rather a response to specific environmental cues. Nutrient scarcity, for instance, acts as a powerful trigger for sporulation in many fungal species. When resources like carbon and nitrogen become limited, fungi such as *Aspergillus* and *Neurospora* initiate sporulation as a means to disperse and seek new habitats. This adaptive response highlights the fungus’s ability to sense and react to its environment, ensuring its genetic continuity even in adverse conditions.

Light, another critical environmental factor, plays a nuanced role in sporulation. For example, in *Neurospora crassa*, exposure to blue light accelerates the development of spores by activating specific photoreceptors. Conversely, some fungi, like certain species of *Trichoderma*, exhibit reduced sporulation under continuous light, preferring dim or dark conditions. These contrasting responses underscore the diversity in how fungi interpret and respond to light cues. Practical applications of this knowledge include optimizing laboratory conditions for fungal cultures, where controlled light exposure can enhance or inhibit sporulation depending on the desired outcome.

Humidity, too, is a pivotal environmental trigger for sporulation. High humidity levels often signal a favorable environment for spore germination, prompting fungi to produce spores in anticipation of successful dispersal. For instance, *Penicillium* species thrive in damp environments, and their sporulation rates increase significantly under humid conditions. However, excessive moisture can also lead to spore degradation, creating a delicate balance that fungi must navigate. Gardeners and farmers can leverage this understanding by managing humidity levels to control fungal growth, either encouraging beneficial fungi or suppressing pathogens.

The interplay of these environmental triggers—nutrient scarcity, light, and humidity—demonstrates the sophistication of fungal reproductive strategies. Each factor acts as a signal, guiding the fungus to allocate resources toward sporulation when conditions are optimal or survival is threatened. For researchers and practitioners, recognizing these triggers opens avenues for manipulating fungal behavior in agriculture, biotechnology, and medicine. By mimicking or altering these environmental cues, it becomes possible to control sporulation, whether to enhance beneficial fungal activity or mitigate harmful outbreaks.

In practical terms, understanding these triggers allows for targeted interventions. For example, in indoor environments, reducing humidity below 60% can inhibit mold sporulation, while in biotechnological settings, controlled nutrient depletion can induce spore production in desired fungal strains. Such precision not only advances scientific knowledge but also translates into tangible benefits, from improving crop health to optimizing industrial fermentation processes. The environmental triggers of sporulation, therefore, are not just biological phenomena but actionable insights with wide-ranging applications.

Buying Magic Mushroom Spores in the UK: Legal or Not?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fungi produce spores through specialized structures like sporangia, basidia, or asci, depending on the fungal group. These structures undergo meiosis or mitosis to generate spores, which are then released into the environment.

Fungi produce various types of spores, including asexual spores (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores) and sexual spores (e.g., basidiospores, asci spores, zygospores). Each type serves specific roles in reproduction and dispersal.

Fungal spores disperse through air, water, animals, or insects. Some spores are lightweight and carried by wind, while others stick to surfaces or are transported by vectors like insects or water currents.