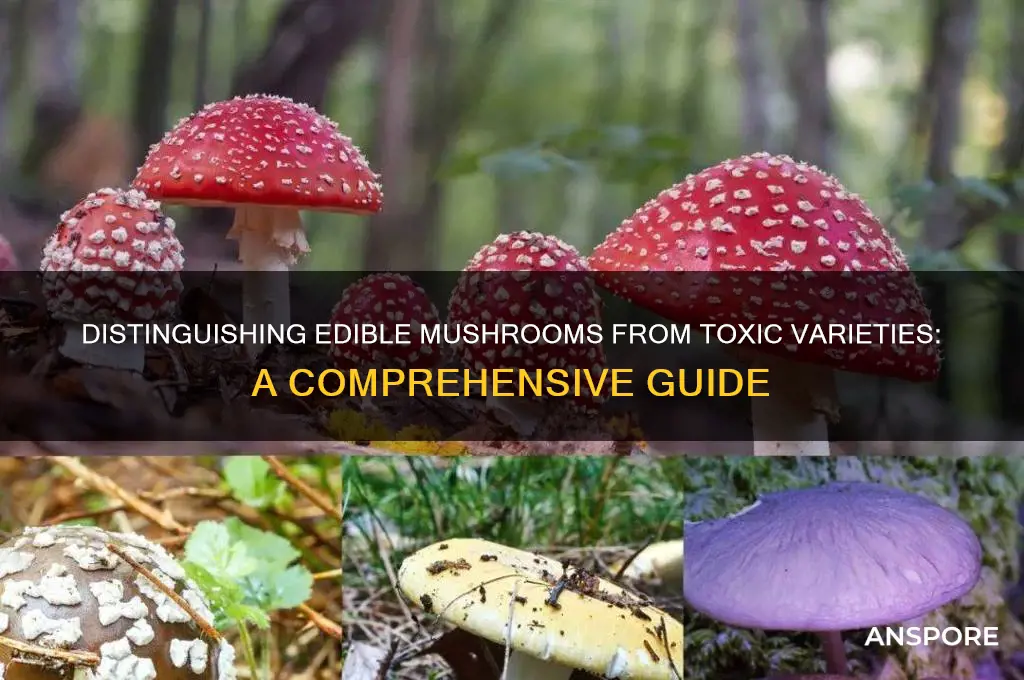

When distinguishing between dealt (poisonous) mushrooms and edible ones, it is crucial to rely on accurate identification methods rather than myths or guesswork. Edible mushrooms, such as button, shiitake, and chanterelles, are cultivated or foraged with care, ensuring they meet safety standards for consumption. In contrast, poisonous mushrooms, like the deadly Amanita species, often resemble edible varieties but contain toxins that can cause severe illness or even death. Key differences include physical characteristics such as cap shape, gill color, spore print, and the presence of a ring or volva at the base. Additionally, edible mushrooms typically grow in specific environments, while poisonous ones may appear in similar habitats, making expert knowledge or field guides essential for safe foraging. Misidentification can be life-threatening, so it is always advisable to consult a mycologist or avoid wild mushrooms unless absolutely certain of their edibility.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Identification Tips: Learn key features to distinguish toxic mushrooms from safe, edible varieties

- Common Look-Alikes: Beware of poisonous species that closely resemble popular edible mushrooms

- Habitat Clues: Understand where edible mushrooms grow vs. toxic environments

- Taste & Smell Myths: Relying on taste or smell can be dangerous for identification

- Preparation Safety: Proper cleaning and cooking methods for edible mushrooms to avoid risks

Identification Tips: Learn key features to distinguish toxic mushrooms from safe, edible varieties

Mushroom identification is a skill that can mean the difference between a delightful meal and a dangerous mistake. While some toxic mushrooms resemble their edible counterparts, key features can help you distinguish between the two. For instance, the Death Cap (Amanita phalloides) often mimics the edible Paddy Straw mushroom (Volvariella volvacea) but has a distinctive cup-like volva at the base and a ring on the stem—features absent in its safe lookalike. Learning such specific traits is crucial for safe foraging.

One analytical approach to identification involves examining the mushroom’s anatomy. Edible varieties like the Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius) have forked, wrinkled gills and a fruity aroma, while toxic species like the Jack-O-Lantern (Omphalotus olearius) have true gills and a sharp, unpleasant smell. Additionally, spore color can be a telltale sign: white or cream spores are common in edible mushrooms, whereas green or black spores often indicate toxicity. Always carry a spore print kit to verify this feature in the field.

Persuasive arguments for caution center on the dangers of relying solely on color or shape. For example, the edible Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus) and the toxic False Morel (Gyromitra spp.) both have unique, sponge-like appearances but differ in texture and habitat. False Morels grow in decaying wood, while Lion’s Mane prefers living trees. This highlights the importance of considering multiple factors, such as habitat, season, and associated flora, when identifying mushrooms.

A comparative analysis of stem features can also be enlightening. Edible mushrooms like the Shiitake (Lentinula edodes) typically have smooth, sturdy stems, whereas toxic species like the Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera) often have bulbous bases and fragile stems. Furthermore, edible varieties rarely have scales or patches on their stems, unlike their toxic counterparts. Always inspect the stem closely, as it can provide critical clues.

Finally, a descriptive guide to cap characteristics is essential. Edible mushrooms such as the Button Mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) have even, unbruised caps, while toxic species like the Conocybe filaris often have irregular shapes or discoloration. Some toxic mushrooms also change color when bruised or cut, a feature absent in most edible varieties. Always carry a knife to test this reaction, but never taste or consume a mushroom based on a single test—multiple identifiers are necessary for safety.

By mastering these identification tips—anatomical analysis, spore color, habitat considerations, stem features, and cap characteristics—you can confidently distinguish toxic mushrooms from safe, edible varieties. Remember, foraging should always be done with caution and, when in doubt, consult an expert or field guide.

Are Bark Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging Practices

You may want to see also

Common Look-Alikes: Beware of poisonous species that closely resemble popular edible mushrooms

The forest floor is a minefield for foragers, where a single misstep can turn a culinary adventure into a toxic ordeal. Among the most treacherous imposters are the Amanita species, often mistaken for the prized Amanita muscaria or the edible Agaricus bisporus. The former, with its vibrant red cap and white flecks, mimics the appearance of certain edible varieties, but contains toxins that can cause severe gastrointestinal distress and, in extreme cases, liver failure. A single cap of the deadly Amanita phalloides, for instance, contains enough amatoxins to kill an adult within 24 to 48 hours if left untreated.

To avoid such dangers, foragers must rely on meticulous observation rather than superficial similarities. For example, the edible puffball (Calvatia gigantea) can be confused with the poisonous Amanita ocreata in its early stages, when both appear as small, white, egg-like structures. However, slicing the specimen in half reveals the truth: a puffball will show a solid, uniform interior, while an Amanita will display the beginnings of a gill structure. This simple test can mean the difference between a delicious meal and a trip to the emergency room.

Another deceptive duo is the chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius) and the jack-o’-lantern (Omphalotus olearius). Both glow in shades of yellow to orange and have a similar wavy-capped appearance. However, the jack-o’-lantern grows in dense clusters on wood, often illuminating decaying trees at night with its bioluminescence. Ingesting this look-alike can lead to severe cramps, vomiting, and dehydration, though its toxins are not typically life-threatening. Chanterelles, on the other hand, grow singly or in small groups on the forest floor and have a distinct fruity aroma.

For novice foragers, the safest approach is to adhere to the "rule of three" identification method: verify the mushroom’s identity using three distinct characteristics, such as spore color, gill attachment, and habitat. Additionally, always carry a field guide or consult an expert before consuming any wild fungi. Even experienced foragers should avoid collecting mushrooms in areas contaminated by pollutants, as toxins like heavy metals can accumulate in fungal tissues, rendering even edible species unsafe.

In the end, the allure of wild mushrooms lies in their diversity and mystery, but this very complexity demands respect and caution. By understanding the subtle differences between edible treasures and their poisonous doppelgängers, foragers can safely enjoy the bounty of the forest without risking their health. Remember: when in doubt, throw it out. No meal is worth the gamble.

Are Rosegill Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging

You may want to see also

Habitat Clues: Understand where edible mushrooms grow vs. toxic environments

Edible mushrooms often thrive in symbiotic relationships with trees, favoring the rich, organic matter found in deciduous and coniferous forests. Look for species like chanterelles and porcini near oak, beech, or pine trees, where their mycorrhizal partnerships flourish. These environments provide the nutrients and shade necessary for their growth, making them prime foraging grounds. In contrast, toxic mushrooms like the deadly Amanita species frequently appear in similar settings, underscoring the need for careful identification. Understanding these ecological ties is the first step in distinguishing safe from dangerous habitats.

Foraging in disturbed or polluted areas significantly increases the risk of encountering toxic mushrooms. Edible varieties are less likely to grow near roadsides, industrial sites, or heavily trafficked trails due to soil contamination and lack of suitable tree partners. Toxic species, however, are more resilient to such conditions, often appearing in these less-than-ideal environments. Always avoid collecting mushrooms from areas where pesticides, herbicides, or heavy metals may be present, as these substances can accumulate in both edible and toxic fungi, rendering even safe species unsafe for consumption.

Moisture and humidity play a critical role in mushroom habitats, but the type of moisture matters. Edible mushrooms like morels prefer well-drained, leafy soil in woodlands, where spring rains create ideal conditions. Toxic species, such as certain Galerina, thrive in damp, decaying wood or waterlogged environments. Pay attention to the substrate—edible mushrooms often grow on living or recently fallen trees, while toxic ones may favor rotting stumps or soggy ground. A hygrometer can help measure humidity levels, but visual cues like moss growth or water pooling are equally telling.

Elevation and climate are additional habitat clues that differentiate edible from toxic mushroom environments. Edible species like matsutake are found in cooler, mountainous regions with specific soil pH levels, often between 5.0 and 6.0. Toxic mushrooms, such as the fly agaric, are more adaptable, appearing across a wider range of altitudes and climates. When foraging at higher elevations, research the local mycoflora to identify species unique to those areas. Similarly, coastal regions may host edible varieties like oyster mushrooms, while inland areas could harbor toxic look-alikes. Always cross-reference habitat data with field guides to ensure accuracy.

Finally, seasonality is a key habitat clue. Edible mushrooms like lion’s mane appear in late summer to fall, coinciding with cooler temperatures and increased tree nutrient exchange. Toxic species, such as the destroying angel, often emerge earlier in the season, taking advantage of spring moisture. Keep a foraging calendar to track when and where specific species appear, noting environmental conditions like temperature, rainfall, and tree phenology. This temporal awareness, combined with spatial knowledge, sharpens your ability to identify safe habitats and avoid toxic ones.

Are Red Ear Mushrooms Edible? A Comprehensive Guide to Safety

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Taste & Smell Myths: Relying on taste or smell can be dangerous for identification

A common misconception among foragers is that toxic mushrooms taste bitter or have a foul odor, while edible ones are pleasant. This myth is dangerous because it oversimplifies a complex issue. Many poisonous mushrooms, such as the deadly Amanita species, can taste mild or even sweet, luring unsuspecting individuals into a false sense of safety. Similarly, some edible mushrooms have an unappealing smell or taste when raw but become delicious when cooked. Relying on taste or smell alone ignores the critical role of chemical compounds that are imperceptible to human senses but can cause severe harm.

Consider the case of the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), one of the most poisonous mushrooms in the world. It has a mild, nutty flavor that has deceived even experienced foragers. Ingesting just 50 grams of this mushroom can be fatal for an adult, causing liver and kidney failure within 24 to 48 hours. Conversely, the edible Paddy Straw mushroom (*Volvariella volvacea*) has a mild taste but can cause allergic reactions in some individuals, demonstrating that taste is not a reliable indicator of safety. These examples highlight the need for a more rigorous identification process than a quick taste test.

Another pitfall is the belief that toxic mushrooms will cause immediate discomfort if tasted. In reality, many poisonous species contain delayed-action toxins that may not produce symptoms for hours or even days. For instance, the toxins in the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) can take 6 to 24 hours to cause symptoms, by which time irreversible organ damage may have occurred. Spitting out a small sample does not guarantee safety, as trace amounts of certain toxins can still be absorbed through the mucous membranes in the mouth. This delay in symptoms further underscores the risk of using taste as a diagnostic tool.

To avoid falling victim to these myths, foragers should adopt a multi-step identification process that includes examining physical characteristics such as cap shape, gill structure, spore color, and habitat. Consulting field guides, using mushroom identification apps, and seeking advice from mycological experts are essential practices. For those new to foraging, starting with easily identifiable species like the Lion’s Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*) or Chanterelles (*Cantharellus cibarius*) can build confidence without unnecessary risk. Remember, the goal is not just to find edible mushrooms but to do so safely, leaving no room for guesswork.

In conclusion, the taste and smell myths perpetuate a dangerous oversimplification of mushroom identification. While sensory cues can provide some information, they are far from foolproof and should never be the sole basis for determining edibility. By understanding the limitations of taste and smell and adopting a more comprehensive approach, foragers can enjoy the rewards of mushroom hunting while minimizing the risks associated with toxic species. Always prioritize caution and education over convenience when it comes to wild mushrooms.

Identifying Yard Mushrooms: Are Your White Mushrooms Safe to Eat?

You may want to see also

Preparation Safety: Proper cleaning and cooking methods for edible mushrooms to avoid risks

Edible mushrooms, while nutritious and versatile, can harbor contaminants like dirt, debris, and even harmful bacteria if not handled correctly. Proper cleaning is the first line of defense against these risks. Unlike vegetables, mushrooms are porous and absorb water quickly, so submerging them in water for extended periods can make them soggy and dilute their flavor. Instead, use a damp cloth or a soft brush to gently wipe away surface impurities. For particularly dirty mushrooms, a quick rinse under cold water followed by immediate patting dry with a paper towel is acceptable. This method ensures cleanliness without compromising texture or taste.

Cooking mushrooms thoroughly is equally critical to eliminate potential pathogens and toxins. Raw mushrooms, especially varieties like shiitake or morel, can cause digestive discomfort or allergic reactions in some individuals. Heat breaks down their cell walls, releasing nutrients like vitamin D and beta-glucans while neutralizing harmful compounds. Aim for a minimum internal temperature of 165°F (74°C) to ensure safety. Sautéing, roasting, or grilling are ideal methods, as they enhance flavor through caramelization while achieving the necessary heat levels. Avoid undercooking, as partially cooked mushrooms may retain risks associated with raw consumption.

While cleaning and cooking are essential, storage practices also play a role in preparation safety. Fresh mushrooms should be stored in paper bags or loosely wrapped in paper towels to maintain optimal moisture levels and prevent spoilage. Refrigerate them in the main compartment, not the crisper drawer, where humidity can accelerate decay. Consume fresh mushrooms within 5–7 days of purchase for peak safety and quality. For longer preservation, drying or freezing are effective methods, but note that dried mushrooms must be rehydrated and cooked before consumption, while frozen mushrooms are best used in cooked dishes rather than raw applications.

Lastly, understanding the source of your mushrooms is a critical aspect of preparation safety. Wild-harvested mushrooms, even if identified as edible, may have been exposed to pollutants, pesticides, or heavy metals from their environment. Cultivated mushrooms, on the other hand, are grown in controlled conditions, reducing these risks. Always purchase mushrooms from reputable suppliers or forage with an experienced guide. When in doubt, consult a mycologist or reference a reliable field guide to confirm edibility. Combining proper sourcing with meticulous cleaning and cooking ensures that the mushrooms on your plate are both safe and delicious.

Can You Eat Crimini Mushrooms Raw? A Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Identifying mushrooms requires careful observation of key features such as cap shape, color, gills, stem characteristics, and spore print. Edible mushrooms often have consistent, well-documented features, while poisonous ones may have look-alikes. Always consult a reliable field guide or expert.

No, there are no universal signs. Some edible mushrooms have toxic look-alikes, and some poisonous mushrooms resemble safe ones. Always verify with multiple identification methods and avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless you are absolutely certain.

No, cooking or boiling does not eliminate toxins from poisonous mushrooms. Many toxins are heat-stable and remain harmful even after preparation. Never assume cooking will make a toxic mushroom safe.

Seek immediate medical attention. Bring a sample of the mushroom or a detailed description to help identify the species. Symptoms can vary, so early treatment is crucial for the best outcome.

Yes, commercially grown mushrooms from reputable sources are safe to eat. They are cultivated under controlled conditions to ensure they are edible varieties. However, always inspect for spoilage before consumption.