Apogamous plants, which reproduce asexually through a process called apogamy, bypass the typical sexual reproduction cycle and produce spores without fertilization. In these plants, the sporophyte generation dominates, and the gametophyte stage is either reduced or absent. Apogamous spore production occurs when the sporophyte directly forms spores through meiosis, often within specialized structures like sporangia. This method ensures genetic uniformity among offspring since there is no exchange of genetic material. Examples of apogamous plants include certain ferns and some species of liverworts, where this mechanism allows for rapid and efficient reproduction in stable environments, though it limits genetic diversity compared to sexually reproducing counterparts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Mode of Reproduction | Asexual (Apogamy) |

| Sporophyte Formation | Sporophyte develops directly from gametophyte tissue without fertilization |

| Type of Spores Produced | Spores are typically diploid (2n) |

| Structure Involved | Sporangia develop on the gametophyte (often on leaves or stems) |

| Meiosis Involvement | Meiosis is bypassed; spores are produced through mitosis |

| Genetic Variation | Limited genetic diversity due to lack of fertilization and meiosis |

| Examples of Plants | Ferns (e.g., Dryopteris), some mosses, and certain liverworts |

| Environmental Trigger | Often occurs in stable, favorable environments where sexual reproduction is less advantageous |

| Advantages | Rapid reproduction, ability to colonize new habitats quickly |

| Disadvantages | Reduced genetic diversity, vulnerability to environmental changes |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Apogamy definition: Asexual reproduction in plants, bypassing fertilization, producing spores without gamete fusion

- Sporophyte dominance: Sporophyte generation persists, directly forming spores without gametophyte involvement

- Spore formation sites: Sporangia develop on leaves, stems, or other sporophyte tissues

- Mitotic spore production: Spores form via mitosis, not meiosis, maintaining sporophyte chromosome number

- Environmental triggers: Stress factors like drought or nutrient deficiency induce apogamous spore formation

Apogamy definition: Asexual reproduction in plants, bypassing fertilization, producing spores without gamete fusion

Apogamous plants challenge the traditional reproductive norms by producing spores asexually, eliminating the need for fertilization. This process, known as apogamy, occurs when the female gametophyte develops into an embryo without the fusion of gametes. For instance, in certain ferns like the *Dryopteris* species, the egg cell within the archegonium divides mitotically, forming an embryo directly. This bypasses the typical sexual reproduction pathway, offering a rapid and efficient means of propagation. Such mechanisms are particularly advantageous in stable environments where genetic diversity is less critical than quick colonization.

To understand apogamy, consider it as a shortcut in the plant life cycle. Normally, plants alternate between a sporophyte and gametophyte phase, with sexual reproduction occurring in the latter. In apogamous plants, however, the gametophyte stage is either reduced or modified to produce spores directly. For example, in some liverworts, the gametophyte generates sporophytes through asexual budding, ensuring genetic uniformity. This method is not just a survival strategy but a testament to the adaptability of plant reproductive systems. Gardeners and botanists can exploit this trait by propagating apogamous species through spore collection, ensuring consistent traits in cultivated varieties.

From a practical standpoint, apogamy offers unique opportunities for horticulture and agriculture. Species like the *Selaginella* (spikemoss) produce spores through apogamy, allowing for mass propagation without the need for pollination. To harness this, collect spores from mature plants during their reproductive phase, typically in late summer or early autumn. Sow these spores in a sterile, moisture-retained medium, maintaining a temperature of 20–25°C for optimal germination. This method is particularly useful for preserving rare or endangered species, as it ensures genetic fidelity without relying on sexual reproduction.

Comparatively, apogamy contrasts sharply with sexual reproduction, which promotes genetic diversity through recombination. While sexual reproduction is advantageous in changing environments, apogamy thrives in stable conditions where rapid growth and uniformity are prioritized. For instance, in monoculture plantations, apogamous species like certain ferns can dominate due to their ability to reproduce quickly without external pollinators. However, this lack of genetic diversity can make them vulnerable to diseases or environmental shifts, underscoring the trade-offs inherent in asexual reproduction.

In conclusion, apogamy represents a fascinating adaptation in plant reproduction, offering a streamlined approach to spore production. By bypassing fertilization, apogamous plants ensure efficiency and uniformity, traits valuable in both natural ecosystems and cultivated settings. Whether you're a botanist studying plant evolution or a gardener seeking reliable propagation methods, understanding apogamy provides insights into the versatility of plant life cycles. Practical applications, from spore collection to controlled environments, highlight its relevance in both scientific and horticultural contexts.

Hand Sanitizer vs. Fungal Spores: Does It Effectively Kill Them?

You may want to see also

Sporophyte dominance: Sporophyte generation persists, directly forming spores without gametophyte involvement

Apogamous plants bypass the typical alternation of generations, where both sporophyte and gametophyte stages are necessary for reproduction. In sporophyte-dominant apogamy, the sporophyte generation not only persists but also directly produces spores without relying on a gametophyte intermediary. This mechanism is a shortcut in the reproductive cycle, eliminating the need for fertilization and gametophyte development. Examples include certain ferns like *Salvinia* and some bryophytes, where the sporophyte remains the primary phase, producing spores through structures like sporangia without forming a free-living gametophyte.

Analytically, sporophyte dominance in apogamous plants represents an evolutionary adaptation to stable or predictable environments. By skipping the gametophyte stage, these plants conserve energy and resources, ensuring rapid and efficient spore production. This strategy is particularly advantageous in habitats where water availability is consistent, as gametophytes often require moisture for survival. For instance, in *Salvinia*, the sporophyte directly forms spores on specialized structures, streamlining reproduction and reducing vulnerability to environmental fluctuations.

To understand this process, consider the steps involved. First, the sporophyte plant develops sporangia, the organs responsible for spore formation. Within these sporangia, spores are produced via meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number, ensuring genetic diversity. Unlike in typical alternation of generations, these spores are not dispersed to grow into gametophytes. Instead, they either germinate directly into new sporophytes or remain dormant until conditions are favorable. This direct pathway minimizes energy expenditure and increases reproductive efficiency.

A cautionary note: while sporophyte dominance offers advantages, it limits genetic recombination, which can reduce adaptability to changing environments. Without the gametophyte stage, there is no opportunity for outcrossing, potentially leading to reduced genetic diversity. However, in stable ecosystems, this trade-off is often acceptable, as the benefits of rapid reproduction outweigh the risks. For gardeners or researchers cultivating apogamous plants, maintaining consistent environmental conditions—such as stable humidity and temperature—can enhance spore production and plant health.

In conclusion, sporophyte dominance in apogamous plants is a specialized reproductive strategy that prioritizes efficiency over genetic diversity. By directly forming spores without gametophyte involvement, these plants thrive in predictable environments, conserving resources and accelerating reproduction. Understanding this mechanism not only sheds light on plant evolution but also provides practical insights for horticulture and conservation efforts, particularly in managing species like *Salvinia* or apogamous ferns.

Can Mushroom Spores Harm Your Vegetable Garden? Facts and Tips

You may want to see also

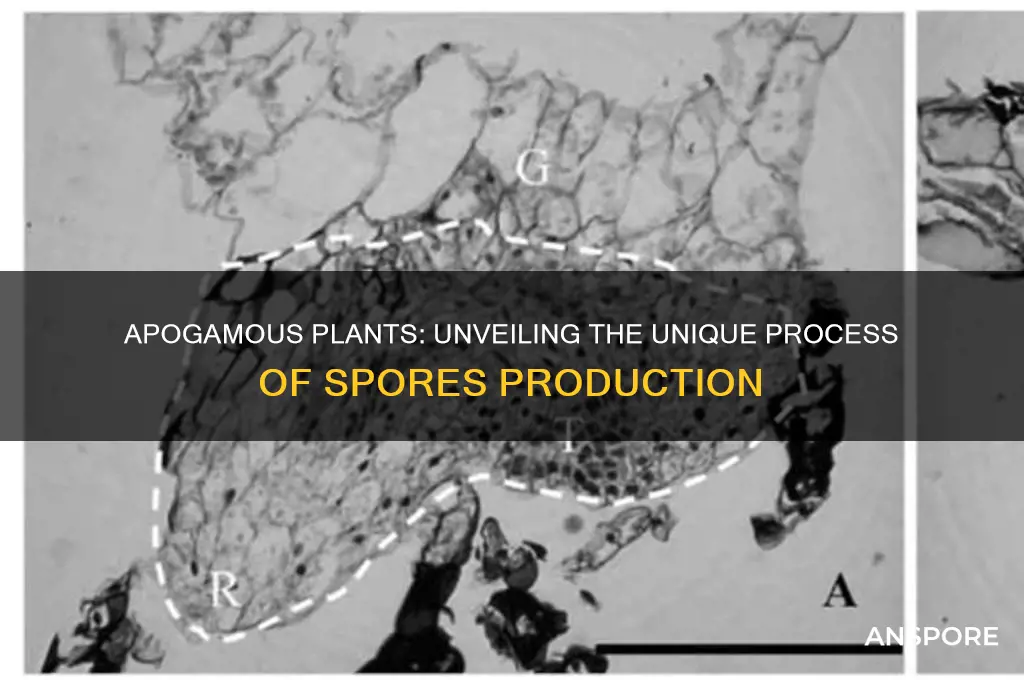

Spore formation sites: Sporangia develop on leaves, stems, or other sporophyte tissues

Apogamous plants, which bypass the typical sexual reproduction process, often produce spores through specialized structures called sporangia. These sporangia are not confined to a single location on the plant but can develop on leaves, stems, or other sporophyte tissues, showcasing the adaptability of these organisms in ensuring their survival and propagation. This strategic placement of sporangia allows apogamous plants to maximize spore dispersal, increasing the likelihood of successful colonization in new environments.

Consider the fern genus *Drynaria*, where sporangia are often found on the undersides of fertile fronds. This positioning is not arbitrary; it facilitates efficient spore release, as the slight movement of the fronds can aid in dispersing spores over a wider area. Similarly, in certain species of lycophytes, sporangia may cluster along the stems, forming distinct patterns that not only serve a reproductive function but also contribute to the plant's overall morphology. Understanding these specific sites of spore formation is crucial for botanists and horticulturists aiming to cultivate or study these plants effectively.

From a practical standpoint, identifying sporangia on leaves or stems can be a useful diagnostic feature for classifying apogamous plants. For instance, in *Selaginella*, sporangia are often differentiated into microsporangia (producing microspores) and megasporangia (producing megaspores), each located in specific regions of the sporophyte. Observing these structures under a 10x hand lens can reveal their arrangement and maturity, aiding in determining the optimal time for spore collection or propagation. This knowledge is particularly valuable for conservation efforts, where preserving genetic diversity through spore banking is essential.

A comparative analysis of sporangial placement across different apogamous species highlights evolutionary strategies tailored to specific habitats. For example, plants in humid environments may have sporangia more exposed to facilitate rapid spore dispersal, while those in arid regions might enclose sporangia within protective structures to prevent desiccation. This diversity in spore formation sites underscores the resilience of apogamous plants in adapting to varying ecological conditions, making them fascinating subjects for both research and application in horticulture.

In conclusion, the development of sporangia on leaves, stems, or other sporophyte tissues is a key mechanism through which apogamous plants produce spores. This adaptability in spore formation sites not only ensures efficient reproduction but also reflects the evolutionary ingenuity of these plants. Whether for scientific study, conservation, or cultivation, understanding these specific structures and their functions provides valuable insights into the biology and ecology of apogamous species.

Can Black Mold Release Lead Spores? Uncovering the Hidden Dangers

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mitotic spore production: Spores form via mitosis, not meiosis, maintaining sporophyte chromosome number

Apogamous plants bypass the typical sexual reproduction cycle, producing spores through mitosis rather than meiosis. This process, known as mitotic spore production, ensures that the resulting spores maintain the same chromosome number as the parent sporophyte. Unlike meiosis, which reduces the chromosome number by half, mitosis preserves the genetic integrity of the parent plant, allowing for rapid and efficient propagation. This mechanism is particularly advantageous in stable environments where genetic diversity is less critical than the ability to quickly colonize an area.

Consider the fern genus *Pteris*, where apogamy is a well-documented phenomenon. In these plants, the prothallus stage—typically a gametophyte that produces gametes—is bypassed entirely. Instead, spores develop directly from the sporophyte via mitotic divisions. This shortcut not only conserves energy but also ensures that the offspring are genetically identical to the parent, a trait valuable in horticulture for maintaining desirable traits in cultivated species. For instance, gardeners propagating a rare fern variety might exploit this process to produce clones without relying on seed viability or cross-pollination.

From a practical standpoint, inducing apogamous spore production can be facilitated by manipulating environmental conditions. Research suggests that stress factors, such as drought or nutrient deficiency, can trigger this response in certain species. For example, exposing *Pteris vittata* to moderate water stress has been shown to increase the frequency of apogamous spore formation. However, caution must be exercised, as excessive stress can lead to plant decline rather than productive adaptation. Optimal conditions for inducing apogamy vary by species, so experimentation is key.

Comparatively, mitotic spore production contrasts sharply with the sexual reproduction seen in most plants. While sexual reproduction promotes genetic diversity through recombination, apogamy prioritizes consistency and speed. This trade-off highlights the evolutionary flexibility of plant reproductive strategies. In unstable environments, sexual reproduction may offer a survival advantage by generating diverse offspring capable of adapting to changing conditions. Conversely, in predictable habitats, the efficiency of apogamy can outcompete sexual reproduction, as seen in certain fern and bryophyte populations.

In conclusion, mitotic spore production in apogamous plants is a fascinating adaptation that leverages mitosis to maintain genetic uniformity. This process offers practical benefits for horticulture and provides insights into plant evolutionary strategies. By understanding the triggers and mechanisms behind apogamy, researchers and gardeners alike can harness this phenomenon to propagate plants more effectively. Whether in the lab or the garden, recognizing the value of mitotic spore production expands our toolkit for plant conservation and cultivation.

Global Yeast Spores: Exploring Varied Characteristics Across Different Regions

You may want to see also

Environmental triggers: Stress factors like drought or nutrient deficiency induce apogamous spore formation

Apogamous plants, under environmental stress, often bypass the typical sexual reproduction process and produce spores as a survival mechanism. Drought, for instance, triggers a cascade of physiological responses in plants like *Selaginella* and *Pteris*, leading to the formation of apogamous spores. When soil moisture drops below 30% field capacity, these plants detect the stress through root-signaling pathways, prompting the diversion of resources to spore production. This rapid response ensures genetic continuity even in arid conditions, showcasing nature’s ingenuity in adversity.

Nutrient deficiency, particularly of essential elements like nitrogen or phosphorus, acts as another potent trigger for apogamous spore formation. In *Equisetum*, for example, a 50% reduction in available nitrogen shifts the plant’s energy from vegetative growth to spore development. This adaptive strategy allows the plant to disperse offspring to potentially more nutrient-rich environments. Gardeners and researchers can mimic this stress by applying controlled nutrient-deficient substrates to study or induce apogamy, though caution is advised to avoid permanent damage to the plant.

Comparatively, while both drought and nutrient deficiency induce apogamy, the underlying mechanisms differ. Drought stress primarily activates abscisic acid (ABA) signaling, a hormone associated with stress tolerance, whereas nutrient deficiency often involves cytokinin and auxin imbalances. Understanding these pathways enables targeted interventions, such as applying ABA analogs to simulate drought stress without actual water deprivation. Such techniques are invaluable in agricultural settings where inducing apogamy could enhance crop resilience.

Practically, inducing apogamous spore formation in controlled environments requires precision. For drought simulation, gradually reduce watering over 7–10 days until soil moisture reaches the critical 30% threshold. For nutrient deficiency, use hydroponic systems with reduced nitrogen (e.g., 5 mM nitrate instead of the standard 10 mM) to observe apogamous responses. Always monitor plants for signs of irreversible stress, such as leaf chlorosis or wilting, and revert to normal conditions if detected. These methods not only aid research but also offer insights into sustainable plant management under changing climates.

In conclusion, environmental stressors like drought and nutrient deficiency serve as powerful triggers for apogamous spore formation, driven by distinct hormonal and physiological pathways. By manipulating these factors, researchers and horticulturists can unlock the potential of apogamy for plant conservation and crop improvement. However, such interventions demand careful calibration to balance stress induction with plant health, ensuring the survival and propagation of these remarkable species.

Effective Techniques to Precipitate Mold Spores for Research and Analysis

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Apogamy is a form of asexual reproduction in plants where spores are produced without fertilization, bypassing the typical sexual reproductive process.

Apogamous plants produce spores through the development of sporophytes directly from gametophytes, often via the growth of a sporangium on the gametophyte without the need for fertilization.

Apogamy is commonly observed in ferns, liverworts, and certain species of algae, where environmental conditions or genetic factors trigger this reproductive strategy.

Yes, the spores produced by apogamous plants are typically genetically identical to the parent plant, as they are formed through asexual reproduction without genetic recombination.

Apogamy allows plants to reproduce rapidly in stable environments, ensuring the survival of successful genetic traits without the need for a mate or fertilization, which can be advantageous in isolated or resource-limited habitats.

![Shirayuri Koji [Aspergillus oryzae] Spores Gluten-Free Vegan - 10g/0.35oz](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61ntibcT8gL._AC_UL320_.jpg)