*Clostridioides difficile* (C. diff) is a spore-forming bacterium that poses a significant health threat, particularly in healthcare settings. One of the key factors contributing to its resilience and ability to cause recurrent infections is its capacity to form highly durable spores. When exposed to stressful conditions, such as nutrient deprivation or antibiotic treatment, C. diff cells undergo a complex process of sporulation, transforming into dormant spores that can survive for extended periods in harsh environments. These spores are resistant to heat, desiccation, and many disinfectants, allowing them to persist on surfaces and in the gastrointestinal tract until they encounter favorable conditions for germination and reactivation. Understanding how C. diff forms spores is crucial for developing effective strategies to prevent and control infections caused by this pathogen.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Process: C. diff cells form spores under stress, ensuring survival in harsh conditions

- Spore Structure: Spores have a thick, protective coat resistant to heat, antibiotics, and disinfectants

- Germination Triggers: Spores activate in the gut, sensing bile acids and other specific signals

- Spore Survival: Spores can persist on surfaces for months, spreading via fecal-oral transmission

- Infection Cycle: Spores colonize the gut, produce toxins, and restart the cycle via spore formation

Sporulation Process: C. diff cells form spores under stress, ensuring survival in harsh conditions

Under stress, *Clostridioides difficile* (C. diff) cells initiate a complex sporulation process, a survival mechanism that allows them to endure harsh environments. This transformation is triggered by nutrient deprivation, particularly the depletion of carbon and nitrogen sources, which signal to the bacterium that its current habitat is no longer hospitable. The process begins with the activation of a genetic cascade, primarily regulated by the *spo0A* gene, which acts as the master switch for sporulation. As the cell responds to these stressors, it undergoes a series of morphological changes, culminating in the formation of a highly resilient spore.

The sporulation process in C. diff is a multi-stage transformation, starting with the asymmetric division of the cell into a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore. The mother cell then engulfs the forespore, creating a protective environment for the developing spore. During this phase, the forespore accumulates dipicolinic acid, a key component that enhances the spore’s resistance to heat, desiccation, and chemicals. This engulfment is followed by the formation of multiple protective layers, including a thick peptidoglycan cortex and a proteinaceous coat, which shield the spore from external threats. The final result is a dormant, metabolically inactive spore capable of surviving for months or even years in adverse conditions.

Understanding this process is critical for healthcare professionals, as C. diff spores are the primary agents of transmission in hospital settings. Spores can persist on surfaces, medical equipment, and hands, making them difficult to eradicate without specialized disinfectants like chlorine-based cleaners. Unlike vegetative cells, spores are not affected by alcohol-based hand sanitizers, emphasizing the need for proper hand hygiene protocols, such as washing with soap and water, in healthcare environments. This knowledge also informs the development of targeted therapies, such as spore germination inhibitors, which aim to prevent spores from reverting to their infectious vegetative form.

From a practical standpoint, preventing C. diff sporulation in clinical settings involves early detection and intervention. Patients at risk, such as those on prolonged antibiotic therapy or with compromised immune systems, should be monitored for symptoms like diarrhea and abdominal pain. Isolation precautions, including dedicated bathrooms and personal protective equipment, can limit spore spread. Additionally, environmental cleaning with sporicidal agents should be performed daily in affected areas. For individuals recovering from C. diff infection, probiotics containing *Lactobacillus* or *Saccharomyces boulardii* may help restore gut flora, though their efficacy varies and should be discussed with a healthcare provider.

In summary, the sporulation process of C. diff is a remarkable adaptation that ensures its survival in hostile environments. By understanding the triggers and mechanisms of spore formation, healthcare providers can implement targeted strategies to control transmission and treat infections effectively. This knowledge bridges the gap between microbiology and clinical practice, offering actionable insights for preventing outbreaks and improving patient outcomes.

Do Dried Morels Retain Their Spores? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Spore Structure: Spores have a thick, protective coat resistant to heat, antibiotics, and disinfectants

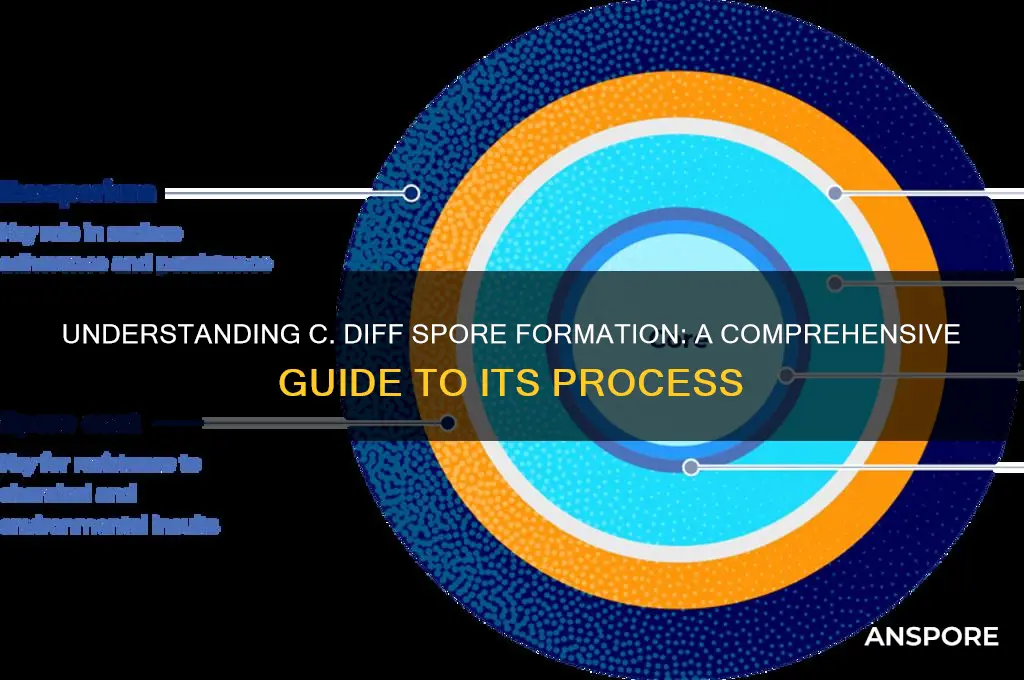

The spore structure of *Clostridioides difficile* (C. diff) is a marvel of evolutionary engineering, designed to ensure survival in hostile environments. At the heart of this resilience is the spore’s thick, protective coat, a multilayered shield that renders it impervious to heat, antibiotics, and disinfectants. This coat, composed of proteins like cotA, cotB, and small acid-soluble proteins (SASPs), forms a rigid exoskeleton that traps DNA within a dehydrated, dormant state. Such a design allows C. diff spores to persist on surfaces for months, resisting temperatures up to 70°C (158°F) and common hospital disinfectants like alcohol-based hand sanitizers. Understanding this structure is critical for healthcare settings, where spores can silently spread via fomites, hands, and equipment, leading to recurrent infections.

To combat C. diff spores, healthcare facilities must adopt targeted disinfection protocols. Unlike vegetative bacteria, spores require sporicidal agents like chlorine-based cleaners (e.g., 1:10 dilution of household bleach) to penetrate the protective coat. For surfaces, a 10-minute contact time with 5,000–10,000 ppm chlorine solution is recommended. In laundry, washing with water ≥71°C (160°F) and bleach-containing detergents can inactivate spores. However, alcohol-based disinfectants, though effective against most pathogens, are ineffective against C. diff spores due to their inability to disrupt the spore coat. This highlights the need for staff education on disinfectant selection and application, particularly in high-risk areas like patient rooms and bathrooms.

The spore coat’s resistance to antibiotics further complicates treatment. Antibiotics like vancomycin and fidaxomicin target active bacterial processes, but spores remain dormant, unaffected by these drugs. Only after germination, when spores revert to vegetative cells, do antibiotics become effective. This explains why C. diff infections often recur post-treatment—residual spores in the gut germinate once antibiotic pressure subsides. Emerging therapies, such as spore germinants paired with antibiotics, aim to address this by forcing spores to germinate prematurely, rendering them vulnerable. For patients, strict hand hygiene with soap and water (not alcohol-based sanitizers) and isolation protocols are essential to prevent spore transmission during treatment.

Comparatively, the spore coat of C. diff shares similarities with other spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus anthracis* (anthrax) but exhibits unique adaptations for gut survival. Unlike *Bacillus* spores, which are primarily soil-dwelling, C. diff spores must withstand bile acids and digestive enzymes in the gastrointestinal tract. The coat’s protein composition likely includes bile acid binding proteins, enhancing resistance to this environment. This specificity underscores the challenge of eradicating C. diff in clinical settings, where spores exploit the gut microbiome’s disruption by antibiotics to colonize and cause disease. Research into coat-specific inhibitors offers hope for future interventions, potentially blocking spore formation or germination without harming beneficial gut flora.

In practical terms, preventing C. diff spore formation and spread requires a multifaceted approach. For at-risk populations (e.g., elderly patients on prolonged antibiotics), probiotics like *Lactobacillus* strains may help restore gut microbiota balance, reducing spore germination opportunities. Environmental cleaning should prioritize sporicidal agents, with regular audits to ensure compliance. Patients and caregivers must be educated on the limitations of alcohol-based sanitizers, emphasizing soap and water use after contact with infected individuals. By targeting the spore coat’s vulnerabilities and adopting evidence-based practices, healthcare systems can mitigate the impact of this resilient pathogen, reducing infection rates and improving patient outcomes.

Do Dry Fruits Contain Spores? Unveiling the Fungal Truth

You may want to see also

Germination Triggers: Spores activate in the gut, sensing bile acids and other specific signals

Spores of *Clostridioides difficile* (C. diff) are masters of dormancy, biding their time until conditions are just right to awaken and cause infection. This activation, known as germination, is not random but triggered by specific signals in the gut environment. Chief among these are bile acids, naturally occurring compounds that aid in fat digestion. When C. diff spores encounter primary bile acids like taurocholate and glycocholate, they interpret this as a cue to exit dormancy. These bile acids bind to receptors on the spore’s surface, initiating a cascade of events that lead to germination. This process is so finely tuned that even slight changes in bile acid concentration can influence spore activation, underscoring the spore’s adaptability in the hostile gut ecosystem.

Understanding the role of bile acids in germination has practical implications for prevention and treatment. For instance, individuals on proton pump inhibitors or antibiotics—both of which alter gut bile acid composition—may inadvertently create an environment conducive to C. diff spore activation. Probiotics containing bile salt hydrolase-producing strains, such as *Lactobacillus* or *Bifidobacterium*, can help mitigate this risk by modifying bile acids into forms less likely to trigger germination. Additionally, emerging therapies like bile acid sequestrants, which bind and remove excess bile acids from the gut, show promise in reducing spore activation. For high-risk patients, such as those over 65 or with compromised immune systems, monitoring bile acid levels and adjusting dietary intake (e.g., reducing high-fat foods) could be a proactive strategy to prevent C. diff infection.

Beyond bile acids, other gut signals play a supporting role in spore activation. Glycine, a simple amino acid abundant in the gut, acts as a co-germinant, enhancing the effect of bile acids. Similarly, certain sugars and salts can modulate germination efficiency, though their impact is less pronounced. Temperature also matters; spores are more likely to germinate at body temperature (37°C), a reminder that the gut’s warmth is another critical factor. This multi-signal requirement ensures that spores only activate in the precise conditions of the intestinal tract, minimizing the risk of premature germination in less hospitable environments.

Clinicians and researchers are leveraging this knowledge to develop targeted interventions. For example, designing drugs that mimic bile acids but fail to trigger germination could act as decoys, effectively "tricking" spores into remaining dormant. Conversely, therapies that block bile acid receptors on spores could prevent activation altogether. In the meantime, simple dietary adjustments—such as increasing fiber intake to promote a healthy gut microbiome—can indirectly reduce the likelihood of spore germination by maintaining a balanced bile acid profile. By focusing on these specific triggers, we move closer to a future where C. diff infections are not just treated but prevented at the source.

Inoculating Mushroom Mycelium with Cold Spores: Risks and Best Practices

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore Survival: Spores can persist on surfaces for months, spreading via fecal-oral transmission

Spores of *Clostridioides difficile* (C. diff) are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving on surfaces for months, even in harsh conditions. This durability stems from their tough outer coat, which protects the bacterial DNA and metabolic machinery from desiccation, heat, and disinfectants. Unlike vegetative cells, spores are metabolically dormant, requiring no nutrients or energy to remain viable. This adaptability makes them a formidable challenge in healthcare settings, where surfaces like bed rails, doorknobs, and medical equipment can become reservoirs for transmission. Understanding this survival mechanism is critical for implementing effective infection control measures.

The primary route of C. diff spore transmission is fecal-oral, a pathway that underscores the importance of hygiene in breaking the chain of infection. Spores shed in feces can contaminate hands, gloves, or environmental surfaces, where they await ingestion by a new host. This is particularly concerning in healthcare facilities, where patients with weakened immune systems or disrupted gut microbiota are highly susceptible. Even trace amounts of fecal matter—invisible to the naked eye—can harbor enough spores to cause infection. Hand hygiene with soap and water is superior to alcohol-based sanitizers for removing spores, as alcohol does little to disrupt their protective coat.

Practical steps to mitigate spore survival and transmission include rigorous environmental cleaning and disinfection. Surfaces should be cleaned with a sporicidal agent, such as a 10% bleach solution (1 part bleach to 9 parts water), left to contact for 10 minutes before wiping. In healthcare settings, daily cleaning of high-touch surfaces is essential, especially in rooms of patients with C. diff infection. For non-healthcare environments, focus on areas prone to fecal contamination, like bathrooms and changing tables. Laundering soiled fabrics in hot water (60°C or higher) and drying at high heat can also inactivate spores.

Comparatively, while alcohol-based hand sanitizers are ineffective against C. diff spores, they remain valuable for general infection control. The key is to pair their use with soap and water, particularly after contact with potentially contaminated materials. This dual approach ensures that vegetative bacteria are killed while spores are physically removed. In healthcare, gloves should be worn when handling bodily fluids or soiled items, but they are not a substitute for hand hygiene, as spores can survive on glove surfaces and transfer to hands during removal.

The takeaway is clear: C. diff spores demand a targeted, evidence-based response. Their persistence on surfaces and fecal-oral transmission route highlight the need for meticulous hygiene practices. By combining sporicidal disinfection, proper handwashing, and awareness of high-risk areas, individuals and institutions can significantly reduce the spread of this resilient pathogen. In the battle against C. diff, knowledge of spore survival is not just academic—it’s actionable.

Meiospores: Understanding Their Sexual or Asexual Nature in Reproduction

You may want to see also

Infection Cycle: Spores colonize the gut, produce toxins, and restart the cycle via spore formation

Observation: *Clostridioides difficile* (C. diff) spores are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving for months on surfaces and resisting stomach acid, making them the primary vehicle for infection. Once ingested, these dormant spores transform into active bacteria, initiating a cycle that can wreak havoc on the gut microbiome.

Steps in the Infection Cycle:

- Spores Colonize the Gut: Upon entering the gastrointestinal tract, C. diff spores germinate in the colon, triggered by bile acids and other environmental cues. This process converts them into vegetative cells, which adhere to the intestinal lining. A healthy gut microbiome typically prevents colonization, but antibiotic use or other disruptions can create an opportunity for C. diff to take hold.

- Toxin Production: Once established, the bacteria produce two potent toxins—TcdA and TcdB—which damage the colon’s epithelial cells. This leads to inflammation, diarrhea, and in severe cases, pseudomembranous colitis. The toxins act by disrupting cell signaling pathways, causing fluid secretion and tissue necrosis. Even small amounts of these toxins (as little as 10 ng/kg body weight) can trigger symptoms.

- Spore Formation and Cycle Restart: As the bacterial population grows, C. diff cells sense overcrowding and begin to form spores again. This process, called sporulation, ensures survival outside the host and prepares the bacteria for transmission. Spores are shed in feces, contaminating surfaces and hands, and can infect new hosts or re-infect the same individual, especially if the microbiome remains imbalanced.

Cautions: Breaking the cycle requires addressing both the active infection and the spore reservoir. Antibiotics like vancomycin or fidaxomicin target vegetative cells but may not eliminate spores, leading to recurrence in up to 35% of cases. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has shown promise by restoring a healthy microbiome, reducing spore germination, and preventing reinfection.

Milky Spore Soil: Effective Grub Control for Lawns and Gardens

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

C. diff (Clostridioides difficile) forms spores through a process called sporulation, which is triggered by environmental stress, such as nutrient depletion or exposure to antibiotics. During sporulation, the bacterium undergoes a series of morphological changes, culminating in the formation of a highly resistant spore.

C. diff spores are extremely resilient and can survive harsh conditions, including heat, dryness, and disinfectants. They can persist in the environment for months, allowing them to spread easily. When ingested, spores can germinate in the gut, leading to infection and causing symptoms like diarrhea and colitis.

Most regular cleaning agents are ineffective against C. diff spores. Specialized disinfectants containing chlorine bleach (sodium hypochlorite) or sporicidal agents are required to kill them. Proper cleaning and disinfection of surfaces are crucial to prevent transmission.

C. diff spores germinate in the human body when they encounter specific conditions in the gastrointestinal tract, such as bile acids and a favorable pH. Once germinated, the spores transform into active bacteria, which can produce toxins and cause infection, particularly in individuals with disrupted gut microbiota, often due to antibiotic use.