Ferns are unique plants that reproduce through spores rather than seeds, and their method of spore dispersal is both fascinating and efficient. Unlike flowering plants, ferns produce tiny, dust-like spores on the undersides of their fronds, typically in structures called sori. When mature, these spores are released into the air, often aided by wind, allowing them to travel significant distances. This dispersal mechanism ensures ferns can colonize new habitats, even in shaded or remote environments where they thrive. Once a spore lands in a suitable moist and shaded location, it germinates into a small, heart-shaped structure called a prothallus, which then facilitates the sexual reproduction process, ultimately leading to the growth of a new fern plant. This cycle highlights the adaptability and resilience of ferns in their natural ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Method of Spores Release | Ferns release spores through structures called sporangia, typically located on the undersides of fertile fronds (leaves). |

| Sporangia Location | Found in clusters called sori, which can be linear, round, or scattered, depending on the fern species. |

| Sporangia Opening | Sporangia open via an annulus (a ring of cells that dries and contracts), allowing spores to be ejected into the air. |

| Spores Size | Spores are microscopic, typically ranging from 20 to 60 micrometers in diameter, enabling wind dispersal. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Primarily dispersed by wind due to their lightweight nature and small size. |

| Distance of Dispersal | Can travel short to long distances, depending on wind conditions, with some spores capable of traveling miles. |

| Spores Viability | Spores can remain viable for extended periods, often years, under favorable conditions. |

| Germination Process | Spores germinate in moist environments, developing into a gametophyte (prothallus), which is a small, heart-shaped structure. |

| Sexual Reproduction | Gametophytes produce sperm and eggs; fertilization occurs when sperm swim to the egg in the presence of water. |

| Environmental Requirements | Spores require moisture for germination and early gametophyte development, making ferns prevalent in humid or shaded environments. |

| Adaptations for Spread | Some ferns have evolved mechanisms like indusia (protective coverings over sori) to shield spores from premature release or harsh conditions. |

| Role of Wind | Wind is the primary agent for spore dispersal, with spore shape and size optimized for aerodynamic travel. |

| Role of Water | Water is essential for sperm mobility during fertilization but not for spore dispersal. |

| Seasonality | Spores are typically released in spring or summer, coinciding with favorable conditions for germination and growth. |

| Ecological Impact | Ferns contribute to ecosystem diversity and soil stabilization, with their spores playing a key role in colonization of new habitats. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Wind Dispersal Mechanisms: Ferns release lightweight spores that are easily carried by wind currents over distances

- Sporangia Structure: Specialized structures called sporangia produce and eject spores for efficient dispersal

- Spores' Lightweight Design: Fern spores are tiny and lightweight, aiding in wind-driven dispersal and wide distribution

- Environmental Triggers: Factors like humidity and temperature influence spore release timing for optimal spread

- Water-Aided Dispersal: Some fern spores can also spread via water, especially in moist environments

Wind Dispersal Mechanisms: Ferns release lightweight spores that are easily carried by wind currents over distances

Ferns have mastered the art of wind dispersal, a strategy that ensures their survival and proliferation across diverse environments. Unlike seeds, fern spores are minuscule, often measuring between 20 to 60 micrometers in diameter, making them incredibly lightweight. This design is no accident; it allows spores to be effortlessly lifted and carried by even the gentlest wind currents. Imagine a single spore, weighing less than a grain of sand, traveling miles from its parent plant to colonize new habitats. This efficiency in dispersal is a testament to the evolutionary ingenuity of ferns, which have thrived for over 360 million years.

To understand the mechanics of wind dispersal, consider the structure of a fern’s sporangia, the sac-like structures where spores are produced. These sporangia are often clustered into sori, which are typically located on the undersides of fronds. When mature, the sporangia dry out and contract, launching spores into the air with remarkable force. This process, known as "ballistic dispersal," is just the first step. Once airborne, the spores’ low mass and aerodynamic shape allow them to remain suspended in wind currents, drifting far beyond their point of origin. For instance, studies have shown that fern spores can travel up to 10 kilometers under favorable conditions, though most settle within a few hundred meters.

Practical observation of this mechanism can be a rewarding experience for gardeners and nature enthusiasts. To witness wind dispersal in action, examine mature fern fronds on a dry, breezy day. Gently tap a frond with a sori cluster over a dark surface, such as a piece of paper, and observe the tiny, dust-like spores being released. These spores are so lightweight that even a slight breeze can carry them away, demonstrating the passive yet effective nature of this dispersal method. For those cultivating ferns, ensuring good air circulation around the plants can enhance spore dispersal, promoting healthier growth and propagation.

While wind dispersal is highly effective, it is not without challenges. Spores are vulnerable to desiccation and predation during their journey, and their success depends on landing in a suitable environment. However, ferns compensate for these risks by producing vast quantities of spores—a single fern can release millions annually. This strategy increases the likelihood that at least some spores will find fertile ground, germinate, and develop into new plants. For conservationists, understanding this mechanism is crucial for protecting fern species in fragmented habitats, where wind corridors can be vital for maintaining genetic diversity.

In conclusion, the wind dispersal of fern spores is a marvel of natural engineering, combining simplicity with efficiency. By producing lightweight, aerodynamic spores and utilizing wind currents, ferns ensure their widespread distribution with minimal energy expenditure. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or simply an admirer of nature’s ingenuity, appreciating this mechanism offers valuable insights into the resilience and adaptability of one of Earth’s oldest plant groups.

Exploring the Connection: Are Darkspore and Spore Related Games?

You may want to see also

Sporangia Structure: Specialized structures called sporangia produce and eject spores for efficient dispersal

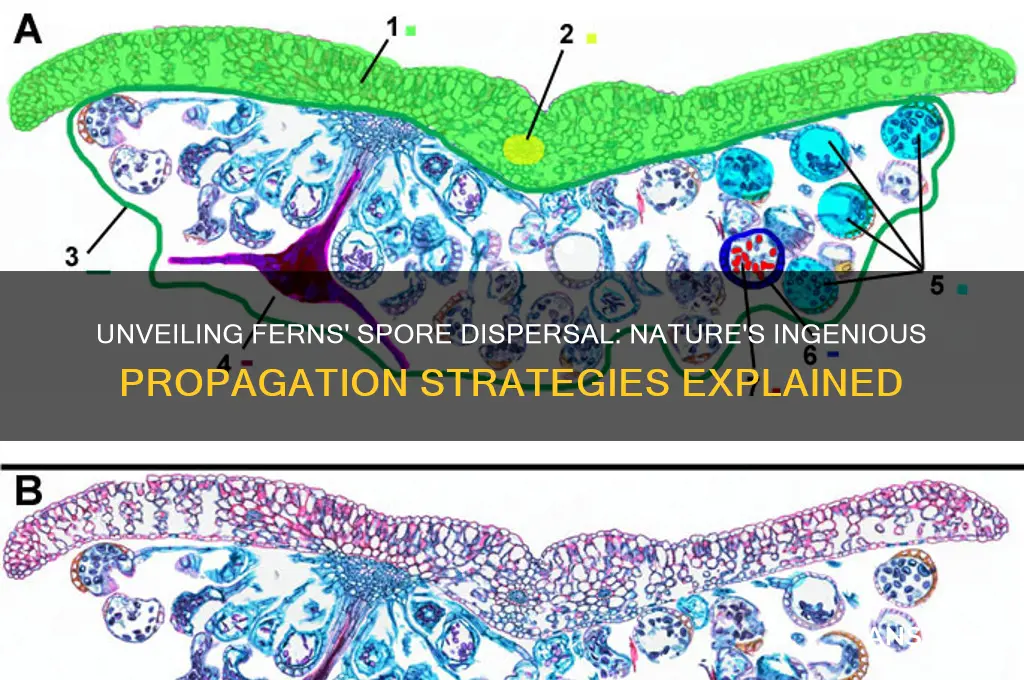

Ferns, unlike flowering plants, rely on spores for reproduction, and the key to their dispersal lies in the intricate design of sporangia. These specialized structures are not merely containers for spores; they are dynamic, precision-engineered mechanisms optimized for efficient release. Located on the undersides of fern fronds, sporangia are typically clustered into groups called sori, which are often protected by a thin, delicate membrane called the indusium. This arrangement ensures that spores are produced in abundance and shielded until the optimal moment for dispersal.

The structure of a sporangium is a marvel of natural engineering. Each sporangium consists of a capsule-like body with a wall that is one cell layer thick, allowing for flexibility and responsiveness to environmental cues. Inside, spore mother cells undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores. The wall of the sporangium is not uniform; it is thicker at the base and thinner at the apex, creating a natural weak point. This design is crucial for the explosive release mechanism. As the sporangium matures, water is drawn out of the cells at the apex, causing them to collapse and form a ring of dead cells. This creates a zone of weakness that, when triggered by environmental factors like humidity or temperature changes, results in the sudden rupture of the sporangium, ejecting the spores with remarkable force.

To understand the efficiency of this system, consider the physics involved. The spores are launched at speeds that can reach several meters per second, a feat achieved without muscles or moving parts. This is made possible by the conversion of elastic potential energy stored in the sporangium wall into kinetic energy during the rupture. The spores are not released randomly but are often directed upward, taking advantage of air currents for long-distance dispersal. This mechanism ensures that even in still air, spores can travel significant distances, increasing the chances of reaching new habitats.

Practical observation of sporangia in action can be a rewarding experience for enthusiasts. To witness spore ejection, collect a mature fern frond with visible sori and place it in a closed container overnight. By morning, the spores will have been released and will settle on the container’s surface, forming a fine, dust-like layer. This simple experiment highlights the effectiveness of sporangia in dispersing spores and underscores their role in the fern life cycle. For educators or hobbyists, this can serve as a hands-on demonstration of plant reproduction, suitable for all age groups.

In conclusion, the sporangia of ferns are not just passive spore producers but active dispersal units finely tuned by evolution. Their structure and function exemplify nature’s ingenuity in solving the challenge of reproduction in non-flowering plants. By studying sporangia, we gain insights into the mechanisms that have allowed ferns to thrive for millions of years, adapting to diverse environments and ensuring their survival through efficient spore dispersal.

How Humidity Triggers Mold Spores: Understanding the Release Process

You may want to see also

Spores' Lightweight Design: Fern spores are tiny and lightweight, aiding in wind-driven dispersal and wide distribution

Fern spores are marvels of natural engineering, designed with a singular purpose: to travel far and wide. Their lightweight structure, typically measuring between 30 to 60 micrometers in diameter, is a key adaptation for wind-driven dispersal. To put this into perspective, a single spore is roughly the size of a grain of fine sand, yet it weighs virtually nothing. This minuscule mass allows spores to remain suspended in air currents for extended periods, increasing their chances of reaching distant, fertile grounds.

Consider the mechanics of this design. Unlike seeds, which rely on animals, water, or gravity for dispersal, fern spores are entirely at the mercy of the wind. Their lightweight nature ensures they can be carried over vast distances, sometimes even crossing geographical barriers like rivers or mountains. For instance, studies have shown that fern spores can travel up to 100 kilometers under favorable wind conditions. This efficiency in dispersal is a testament to the evolutionary perfection of their design, enabling ferns to colonize diverse habitats, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands.

To appreciate the practical implications of this lightweight design, imagine a scenario where ferns rely on heavier spores. Such spores would fall to the ground quickly, limiting their distribution to the immediate vicinity of the parent plant. This would result in overcrowded growth and increased competition for resources. By contrast, the lightweight spores ensure that ferns can spread thinly and widely, maximizing their chances of survival in varied environments. Gardeners and conservationists can leverage this knowledge by strategically placing fern species in open areas where wind flow is consistent, enhancing their natural dispersal mechanisms.

The lightweight design of fern spores also highlights a fascinating trade-off: while it ensures wide distribution, it comes at the cost of reduced protection. Unlike seeds, which often have hard coats or nutrient stores, spores are fragile and lack internal resources. This vulnerability underscores the importance of producing vast quantities of spores—a single fern can release millions annually. For enthusiasts cultivating ferns, this means ensuring optimal conditions for spore release, such as adequate light and humidity, to compensate for their delicate nature.

In conclusion, the lightweight design of fern spores is a masterclass in biological efficiency, tailored for wind-driven dispersal and wide distribution. This adaptation not only ensures the survival of fern species across diverse ecosystems but also offers valuable insights for horticulture and conservation efforts. By understanding and respecting this natural design, we can better appreciate the intricate ways in which ferns thrive and propagate in the wild.

Does Halo of Spores Affect Multiple Enemies Simultaneously? A Detailed Analysis

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Triggers: Factors like humidity and temperature influence spore release timing for optimal spread

Ferns, ancient plants with a reproductive strategy finely tuned to their environment, rely on spores for propagation. Unlike seeds, spores are microscopic and lightweight, requiring precise conditions to disperse effectively. Environmental triggers, particularly humidity and temperature, act as critical cues that dictate the timing of spore release, ensuring optimal spread and survival. These factors are not mere coincidences but evolutionary adaptations that maximize the chances of successful colonization in new habitats.

Consider humidity, a key player in spore release. Ferns often thrive in moist environments, and their spore-bearing structures, called sporangia, are sensitive to water vapor levels. High humidity signals the presence of a suitable environment for spore germination, prompting the sporangia to open and release their contents. For instance, many fern species release spores during the early morning or after rainfall when humidity peaks. This timing aligns with the availability of moisture, increasing the likelihood that spores will land on damp surfaces conducive to growth. Practical observation reveals that placing a fern in a humidifier-rich environment can artificially trigger spore release, mimicking natural conditions.

Temperature, another critical environmental trigger, works in tandem with humidity to regulate spore dispersal. Ferns are ectothermic, meaning their physiological processes are influenced by external temperatures. Warmth accelerates metabolic activity, including the maturation and release of spores. However, extreme temperatures can be detrimental, causing desiccation or inhibiting spore viability. Optimal spore release typically occurs within a narrow temperature range, often between 20°C and 25°C (68°F and 77°F), depending on the species. Gardeners and botanists can exploit this knowledge by monitoring temperature fluctuations to predict and manage spore release, ensuring successful propagation in controlled settings.

The interplay between humidity and temperature creates a delicate balance that ferns have mastered over millennia. For example, in tropical regions, where both humidity and temperature are consistently high, ferns release spores year-round. In contrast, temperate species often synchronize spore release with seasonal changes, such as the onset of spring when humidity rises and temperatures warm. This adaptability highlights the fern’s ability to respond dynamically to environmental cues, optimizing spore dispersal across diverse ecosystems.

Understanding these environmental triggers offers practical applications for conservation and horticulture. By replicating natural conditions—maintaining humidity levels above 70% and temperatures within the optimal range—enthusiasts can encourage spore release in cultivated ferns. Additionally, this knowledge aids in preserving fern habitats, as disruptions to humidity and temperature patterns, such as deforestation or climate change, could destabilize spore dispersal mechanisms. In essence, the environmental triggers governing spore release are not just biological phenomena but vital components of fern survival and propagation strategies.

Does North Spore Sell Psychedelic Mushrooms? Exploring Legal Boundaries

You may want to see also

Water-Aided Dispersal: Some fern spores can also spread via water, especially in moist environments

Ferns, with their ancient lineage, have mastered the art of survival through ingenious spore dispersal methods. Among these, water-aided dispersal stands out as a particularly fascinating strategy, especially in moist environments where water is abundant. This method leverages the natural flow of water to transport spores over distances, ensuring the colonization of new habitats. Unlike wind dispersal, which relies on air currents, water dispersal is more localized but equally effective in the right conditions.

Consider the process: when fern spores are released, they often land on wet surfaces or are washed into streams, rivers, or even rainwater runoff. These spores, being lightweight and hydrophobic, can float on the water’s surface, traveling with the current until they reach a suitable substrate. For instance, in tropical rainforests, where humidity is high and water bodies are plentiful, fern spores can spread rapidly along riverbanks or in flooded areas. This method is particularly advantageous for species like the *Pteris cretica* (Cretan brake fern), which thrives in wet, shaded environments.

To maximize water-aided dispersal, ferns often produce spores in large quantities, increasing the likelihood that some will encounter water. A single fern can release millions of spores in a single season, ensuring that even if only a fraction are water-dispersed, the species’ survival is secured. Practical tips for observing this phenomenon include visiting riparian zones during the rainy season or placing potted ferns near water features to simulate natural conditions. For enthusiasts, collecting spores from water surfaces using a fine mesh net can provide a hands-on understanding of this dispersal mechanism.

However, water dispersal is not without challenges. Spores must remain viable after prolonged exposure to water, which can be detrimental to many plant species. Ferns have evolved to produce spores with resilient outer walls, allowing them to withstand moisture without germinating prematurely. This adaptation highlights the intricate balance between dispersal and survival, showcasing the evolutionary sophistication of ferns.

In conclusion, water-aided dispersal is a testament to ferns’ adaptability, particularly in moist ecosystems. By harnessing the power of water, these plants ensure their spores reach new territories, perpetuating their presence in diverse habitats. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or nature enthusiast, understanding this mechanism offers valuable insights into the resilience and ingenuity of one of Earth’s oldest plant groups.

Can You Buy Magic Mushroom Spores at Garden Centers?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Ferns spread their spores through a process called sporulation. Spores are produced in structures called sporangia, which are typically located on the undersides of the fern's fronds. When mature, the sporangia release the spores into the air, allowing them to disperse.

Fern spores are located in sporangia, which are often clustered into groups called sori. These sori are usually found on the undersides of the fern's mature fronds, though their exact location and arrangement vary among fern species.

Fern spores are lightweight and can be carried by wind over short to moderate distances, typically ranging from a few meters to several kilometers, depending on wind conditions and spore size. Some spores may also be transported by water or animals.

Once fern spores land in a moist, suitable environment, they germinate into a prothallus, a small, heart-shaped gametophyte. The prothallus produces male and female reproductive cells. After fertilization, a new fern plant (the sporophyte) grows from the prothallus, completing the life cycle.