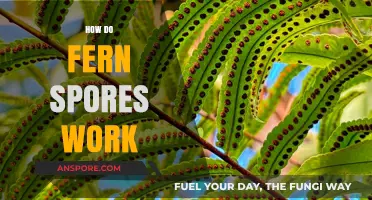

Flood spores, also known as water mold spores, are microscopic reproductive structures produced by certain fungi-like organisms, particularly those in the class Oomycetes. These spores play a crucial role in the life cycle of these organisms, enabling them to survive and spread in aquatic or damp environments. When conditions are favorable, such as during heavy rainfall or flooding, flood spores are released into the water, where they can disperse over long distances. Upon encountering a suitable host, such as a plant or organic matter, the spores germinate, penetrating the host tissue and initiating infection. This process allows the organism to absorb nutrients from the host, leading to decay or disease. Understanding how flood spores work is essential for managing plant diseases, protecting ecosystems, and mitigating the impacts of waterborne pathogens in agriculture and natural environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Flood spores are specialized reproductive structures produced by certain fungi and plants to survive and disperse during flood conditions. |

| Purpose | To ensure survival and propagation in waterlogged or flooded environments. |

| Production | Produced by fungi (e.g., Aspergillus, Penicillium) and some plants in response to high moisture levels. |

| Structure | Typically lightweight, buoyant, and resistant to water damage. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Dispersed by water currents, allowing them to travel long distances during floods. |

| Dormancy | Can remain dormant for extended periods until favorable conditions (e.g., receding water) return. |

| Germination | Germinate when water recedes and conditions become suitable for growth (e.g., soil exposure, nutrients). |

| Adaptations | Possess thick cell walls, hydrophobic surfaces, and protective coatings to withstand harsh aquatic conditions. |

| Ecological Role | Play a key role in ecosystem recovery post-flood by colonizing and stabilizing disturbed areas. |

| Human Impact | Can contribute to mold growth in flood-damaged buildings and pose health risks if inhaled. |

| Research Significance | Studied for their resilience mechanisms, potential applications in biotechnology, and climate adaptation. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Release Mechanisms: Flood spores are released from sediment when disturbed, often by water flow

- Dormancy and Survival: Spores remain dormant in soil for years, surviving harsh conditions until optimal growth triggers

- Germination Process: Spores germinate when exposed to moisture, warmth, and nutrients, initiating fungal growth

- Dispersal Methods: Water, wind, and animals aid in dispersing spores to new environments for colonization

- Ecological Impact: Flood spores contribute to nutrient cycling, decomposition, and ecosystem recovery post-flood events

Spore Release Mechanisms: Flood spores are released from sediment when disturbed, often by water flow

Flood spores, often associated with certain fungi and plants, are dormant structures that can remain viable in sediment for extended periods. Their release mechanism is intricately tied to environmental disturbances, particularly water flow. When sediment is agitated by moving water, such as during floods or heavy rains, the spores are dislodged and carried away, initiating their dispersal. This process is not random but a survival strategy honed by evolution, ensuring that spores reach new habitats where they can germinate and thrive. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for fields like ecology, agriculture, and disaster management, as it sheds light on how species propagate and adapt to changing environments.

The release of flood spores is a multi-step process that begins with sediment disturbance. Water flow acts as the primary catalyst, creating shear forces that break apart the sediment matrix. This action exposes the spores, which are often embedded within protective layers. Once freed, the spores are suspended in the water column, where they can be transported over vast distances. The efficiency of this dispersal depends on factors like water velocity, sediment composition, and spore size. For instance, smaller spores are more easily carried by gentle currents, while larger ones may require more turbulent flow. This natural mechanism highlights the delicate balance between environmental forces and biological adaptation.

To observe this process in action, consider a practical example: a riverbank after a heavy storm. As floodwaters recede, the disturbed sediment reveals a rich reservoir of spores. Ecologists can collect samples and analyze them under a microscope to identify species and assess their viability. For those interested in experimentation, a simple setup involves placing sediment samples in a controlled water flow system, such as a flume, and monitoring spore release over time. This hands-on approach not only demonstrates the mechanism but also allows for the study of variables like flow rate and sediment type. Practical tips include using fine mesh filters to capture spores and maintaining water temperatures that mimic natural conditions.

From a comparative perspective, flood spore release mechanisms differ significantly from those of air-dispersed spores, such as pollen or fungal spores. While air dispersal relies on wind currents and lightweight structures, flood spores depend on water movement and robust, resilient forms. This distinction underscores the diversity of dispersal strategies in nature. For instance, flood spores often have thicker walls or adhesive coatings to withstand harsh aquatic environments, whereas air-dispersed spores prioritize lightness and aerodynamic design. Recognizing these differences is essential for predicting how species respond to environmental changes, such as altered water flow patterns due to climate change or human activities.

In conclusion, the release of flood spores from sediment when disturbed by water flow is a fascinating and ecologically significant process. By understanding the mechanics behind this mechanism, we gain insights into the resilience and adaptability of certain species. Whether through observational studies, controlled experiments, or comparative analyses, exploring flood spore release offers practical knowledge and broader implications for environmental science. For those looking to delve deeper, combining field observations with laboratory experiments can provide a comprehensive understanding of this natural phenomenon, paving the way for informed conservation and management strategies.

Understanding Mold Spores: Size, Visibility, and Health Implications

You may want to see also

Dormancy and Survival: Spores remain dormant in soil for years, surviving harsh conditions until optimal growth triggers

Spores, particularly those of flood-adapted fungi and plants, are nature's time capsules, engineered to endure adversity. Encased in a protective shell, they can lie dormant in soil for decades, biding their time until conditions are just right for germination. This survival strategy is crucial in flood-prone areas, where waterlogged soil and unpredictable weather would otherwise spell doom for less resilient organisms. The key to their longevity lies in their ability to shut down metabolic processes, reducing energy consumption to near zero and minimizing damage from harsh environmental factors like extreme temperatures, drought, or chemical exposure.

Consider the *Alternaria* or *Fusarium* fungi, common flood spore survivors. These spores can persist in soil for up to 10 years, waiting for the right combination of moisture, temperature, and nutrients to activate. Their dormancy is not passive; it’s a finely tuned response to environmental cues. For instance, some spores require a period of cold stratification (exposure to low temperatures) before they can germinate, a mechanism that ensures they don’t sprout prematurely during a fleeting warm spell. This adaptability is a testament to the evolutionary sophistication of flood spores, which have mastered the art of patience in the face of uncertainty.

To harness this survival mechanism in practical applications, such as agriculture or ecological restoration, understanding the triggers for spore activation is essential. For example, farmers in flood-prone regions can use flood-tolerant crop varieties with spores that remain dormant during inundation but sprout rapidly once water recedes. A key tip is to test soil samples for spore viability using a simple germination assay: mix 1 gram of soil with 10 ml of sterile water, incubate at 25°C for 7 days, and observe under a microscope for sprouting spores. This method helps assess the soil’s potential to support plant growth post-flood.

Comparatively, flood spores outshine other survival strategies in their ability to withstand not just one, but multiple stressors simultaneously. While seeds of some plants might survive a single season of drought, flood spores can endure years of waterlogging, salinity, and nutrient depletion. This makes them invaluable in rehabilitating degraded lands or preparing ecosystems for climate change. For instance, in the Mississippi Delta, flood-adapted spores of *Zostera* (eelgrass) are being reintroduced to restore wetlands, where their dormancy ensures they can survive until the next flood cycle brings optimal conditions for growth.

In conclusion, the dormancy of flood spores is a marvel of biological engineering, offering lessons in resilience and resource conservation. By studying their mechanisms, we can develop strategies to protect crops, restore ecosystems, and even inspire new technologies in fields like astrobiology, where survival in extreme conditions is paramount. Whether you’re a farmer, ecologist, or simply curious about nature’s ingenuity, understanding how flood spores work provides a blueprint for thriving in an unpredictable world.

Are C. Botulinum Spores Harmful to Human Health?

You may want to see also

Germination Process: Spores germinate when exposed to moisture, warmth, and nutrients, initiating fungal growth

Spores, the resilient reproductive units of fungi, lie dormant until conditions trigger their awakening. This germination process is a precise dance of environmental cues: moisture, warmth, and nutrients. Imagine a seed waiting for spring—except these spores can endure extreme conditions, from arid deserts to frozen tundra, until the right moment arrives. When water infiltrates their protective casing, it rehydrates the spore’s internal structures, reactivating metabolic processes. Simultaneously, warmth accelerates enzymatic activity, breaking down stored energy reserves. Nutrients, often present in organic matter like soil or decaying material, provide the building blocks for growth. Together, these factors signal the spore to sprout a hypha, the filamentous structure that marks the beginning of fungal colonization.

To understand this process practically, consider a flooded basement. After water intrusion, the environment becomes a spore’s paradise. Moisture softens surfaces, allowing spores to absorb water and swell. Temperatures between 20°C and 30°C (68°F–86°F) create an ideal incubator, speeding up germination. Organic debris, such as wood or drywall, supplies the necessary nutrients. Within 24 to 48 hours, visible mold colonies can emerge, spreading rapidly if left unchecked. This scenario underscores why prompt drying and cleaning are critical after water damage—depriving spores of moisture and nutrients can halt germination before it starts.

From a comparative perspective, spore germination resembles the activation of bacterial endospores, both being survival mechanisms in harsh conditions. However, fungal spores are more versatile, requiring only basic resources to thrive. Unlike endospores, which often need extreme heat or chemical triggers to germinate, fungal spores respond swiftly to everyday environmental changes. This adaptability explains why fungi are among the first colonizers of disturbed ecosystems, from post-wildfire landscapes to water-damaged homes. Their ability to remain dormant yet responsive makes them both ecologically vital and domestically problematic.

For those dealing with flood-prone areas or water damage, proactive measures can disrupt the germination process. Maintain indoor humidity below 60% using dehumidifiers, as spores struggle to absorb moisture in drier conditions. Keep temperatures cooler in unused spaces, as warmth accelerates germination. Regularly inspect and remove organic debris, such as leaves or mulch, near foundations, as these provide nutrient sources. In the event of flooding, dry affected areas within 24–48 hours to starve spores of the moisture they need. While spores are ubiquitous, controlling their environment remains the most effective defense against unwanted fungal growth.

Equisetum Spores' Elaters: Unveiling Their Unique Function and Mechanism

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dispersal Methods: Water, wind, and animals aid in dispersing spores to new environments for colonization

Flood spores, often associated with fungi and certain plants, rely on efficient dispersal methods to colonize new environments. Among the most effective agents are water, wind, and animals, each playing a unique role in transporting spores across diverse landscapes. Water, for instance, acts as a powerful medium, especially during floods, carrying spores over long distances and depositing them in nutrient-rich areas. This method is particularly crucial for species that thrive in moist environments, as it ensures their survival and proliferation in suitable habitats.

Wind dispersal, on the other hand, is a more passive yet widespread mechanism. Spores adapted for wind travel are often lightweight and equipped with structures like wings or hairs, allowing them to remain airborne for extended periods. This method enables colonization of distant and sometimes inaccessible areas, such as mountain slopes or forest canopies. For example, the spores of certain ferns and mushrooms can travel miles, aided by even the gentlest breeze. To maximize wind dispersal, spores are typically released in large quantities, increasing the likelihood of successful colonization.

Animals contribute to spore dispersal through both intentional and unintentional means. Some fungi produce spores with sticky or hook-like structures that attach to animal fur or feathers, hitching a ride to new locations. Others are ingested by animals and pass through their digestive systems unharmed, only to be deposited in fertile environments via feces. A notable example is the relationship between birds and certain plant species, where seeds or spores are dispersed across vast distances as birds migrate. This symbiotic relationship benefits both parties, ensuring the survival of the species involved.

Understanding these dispersal methods is crucial for ecological management and conservation efforts. For instance, in flood-prone areas, knowing how water disperses spores can inform strategies to control invasive species or promote the growth of beneficial fungi. Similarly, wind patterns can be studied to predict the spread of spore-borne diseases in crops or forests. By leveraging this knowledge, practitioners can develop targeted interventions, such as creating windbreaks or implementing animal-friendly habitats, to optimize spore dispersal for desired outcomes.

In practical terms, gardeners and farmers can mimic these natural processes to enhance plant and fungal growth. For water dispersal, strategically placing spore-rich materials near water sources during rainy seasons can encourage colonization in desired areas. Wind dispersal can be aided by elevating spore sources or using fans in controlled environments. Encouraging animal activity through the provision of food or shelter can also facilitate spore transport. By integrating these methods, individuals can harness the power of nature to foster healthier, more resilient ecosystems.

Exploring Galactic Adventures: Can You Purchase It Without Spore?

You may want to see also

Ecological Impact: Flood spores contribute to nutrient cycling, decomposition, and ecosystem recovery post-flood events

Flood spores, often overlooked in ecological discussions, play a pivotal role in the aftermath of flood events. These microscopic entities, primarily fungi and bacteria, are nature’s cleanup crew, rapidly colonizing waterlogged environments to break down organic matter. Their ability to thrive in oxygen-depleted conditions makes them essential for kickstarting decomposition processes, which are otherwise stalled in flooded ecosystems. Without these spores, dead plant material and debris would accumulate, hindering ecosystem recovery. This natural mechanism not only clears the way for new growth but also recycles nutrients back into the soil, ensuring the continuity of ecological functions.

Consider the steps by which flood spores facilitate nutrient cycling. When floodwaters recede, they leave behind a layer of sediment rich in organic debris. Flood spores, dispersed by water currents, quickly colonize this substrate. Fungi, such as *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, secrete enzymes that break down complex organic compounds into simpler forms, like nitrogen and phosphorus. Bacteria, particularly anaerobic species, further decompose these materials, releasing nutrients into the soil. This process is critical in floodplains and wetlands, where nutrient availability directly influences plant regrowth and biodiversity. For instance, in the Mississippi River Basin, post-flood fungal activity has been observed to increase soil nitrogen levels by up to 30% within weeks, accelerating ecosystem recovery.

However, the effectiveness of flood spores in decomposition and nutrient cycling depends on environmental conditions. Temperature, pH, and oxygen levels significantly influence spore activity. For optimal performance, temperatures between 20°C and 30°C are ideal, as this range maximizes enzymatic activity. In colder climates, decomposition slows, delaying nutrient release. Additionally, flood spores thrive in slightly acidic to neutral pH conditions (6.0–7.5). Practitioners in ecosystem restoration should monitor these parameters to ensure spores function efficiently. For example, introducing organic amendments like compost can buffer pH and provide additional substrates for spore colonization, enhancing their impact.

A comparative analysis highlights the unique advantages of flood spores over other decomposition agents. Unlike larger decomposers, such as earthworms or insects, spores can operate in waterlogged soils where oxygen is scarce. This adaptability makes them indispensable in flood-prone areas where other organisms struggle to survive. Moreover, their rapid reproduction rate ensures quick colonization, preventing nutrient loss through leaching. In contrast, relying solely on macroorganisms for decomposition in post-flood scenarios could lead to prolonged recovery times and reduced soil fertility. Thus, flood spores are not just contributors but catalysts in the recovery process.

To maximize the ecological benefits of flood spores, practical interventions can be implemented. After a flood, avoid tilling or disturbing the soil surface, as this disrupts spore colonies. Instead, apply a thin layer of straw or mulch to protect spores while allowing them to access organic matter. In agricultural settings, planting cover crops like clover or rye post-flood can provide additional organic material for spores to decompose, further enriching the soil. For urban areas, incorporating flood-tolerant plants, such as willows or sedges, into green spaces can enhance spore activity by providing consistent organic inputs. These strategies, combined with natural spore processes, create a synergistic effect that accelerates ecosystem recovery and resilience.

Can Breloom Learn Spore? Move Relearner Guide for Pokémon Trainers

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Flood spores are microscopic, dormant structures produced by certain fungi and plants that can survive harsh conditions. They activate and germinate when exposed to water, allowing them to grow rapidly in flooded environments.

Flood spores are typically dispersed by water currents, wind, or animals during flooding events. Once they reach a suitable moist environment, they attach to surfaces, absorb water, and begin to grow, forming new fungal or plant colonies.

While most flood spores are harmless, some can cause issues. Certain fungal spores may lead to mold growth indoors, affecting air quality and health. In ecosystems, they play a natural role in decomposition but can disrupt habitats if they overgrow.