Fungi reproduce through both asexual and sexual means, utilizing spores as their primary dispersal units, but the types of spores produced and the mechanisms of their formation differ significantly between these two reproductive strategies. Asexual spores, such as conidia or zoospores, are typically produced by a single parent through mitosis, allowing for rapid proliferation and adaptation to favorable conditions, though they lack genetic diversity. In contrast, sexual spores, such as asci or basidiospores, result from the fusion of gametes (often from two compatible individuals) through meiosis, which introduces genetic recombination and increases diversity, making fungi more resilient to environmental changes and stressors. These differences highlight the distinct ecological roles and evolutionary advantages of asexual and sexual spore production in fungal life cycles.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Reproduction | Asexual spores are produced through mitosis, resulting in genetically identical offspring (clones). Sexual spores are produced through meiosis and fertilization, resulting in genetically diverse offspring. |

| Genetic Diversity | Low (clonal); no genetic recombination. High; genetic recombination occurs during meiosis and fertilization. |

| Parent Required | Only one parent is needed. Two compatible parents (usually of different mating types) are required. |

| Sporangiospores vs. Zygospores | Asexual spores are often called sporangiospores, produced in sporangia. Sexual spores are often called zygospores, asci, or basidiospores, depending on the fungal group. |

| Examples of Spores | Conidia, sporangiospores, chlamydospores. Zygospores, asci, basidiospores, ascospores. |

| Function | Primarily for rapid dispersal and survival in unfavorable conditions. Primarily for genetic diversity, survival, and long-term persistence. |

| Structure | Often single-celled and simple in structure. Often multicellular or more complex, with specialized structures (e.g., asci, basidia). |

| Production Time | Produced quickly in response to environmental cues. Requires more time due to the need for mating and meiosis. |

| Environmental Resistance | Generally less resistant to harsh conditions compared to sexual spores. Often more resistant to harsh conditions, aiding in long-term survival. |

| Role in Life Cycle | Dominant in the life cycle of many fungi, especially in favorable conditions. Typically part of a more complex life cycle, often triggered by stress or specific environmental cues. |

| Examples of Fungi | Yeasts (e.g., Saccharomyces), molds (e.g., Penicillium). Mushrooms (e.g., Agaricus), smuts, rusts, and many other fungi with complex life cycles. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporangiospores vs. Conidia: Asexual spores produced in sporangia differ from conidia, which form at hyphae ends

- Zygospores Formation: Sexual spores result from zygote fusion, encased in thick, protective walls

- Ascospores and Basidiospores: Sexual spores formed in asci or on basidia, respectively, via meiosis

- Environmental Triggers: Sexual spores often require specific conditions, while asexual spores are more adaptable

- Genetic Diversity: Sexual spores increase diversity via recombination; asexual spores clone the parent fungus

Sporangiospores vs. Conidia: Asexual spores produced in sporangia differ from conidia, which form at hyphae ends

Fungi produce an astonishing array of spores, each tailored to specific survival strategies. Among asexual spores, sporangiospores and conidia stand out for their distinct origins and functions. Sporangiospores develop within a specialized structure called a sporangium, typically at the end of a stalk or within a hyphal network. In contrast, conidia form directly on the tips or sides of hyphae, the filamentous cells that make up fungal bodies. This fundamental difference in formation dictates their dispersal mechanisms, environmental resilience, and ecological roles.

Consider the lifecycle of Zygomycota, a group of fungi that exemplifies sporangiospore production. When conditions are favorable, Zygomycota hyphae develop a swollen sporangium, often elevated on a stalk. Inside, nuclei undergo mitosis, and sporangiospores are produced in large quantities. Upon maturity, the sporangium wall ruptures, releasing spores into the air. This method ensures widespread dispersal but relies on external forces like wind or water. Conidia, on the other hand, are produced by fungi like Aspergillus and Penicillium. These spores form asexually at the ends of specialized hyphae called conidiophores. Their localized formation allows for rapid release in response to environmental cues, such as humidity changes or nutrient availability.

The structural differences between sporangiospores and conidia also influence their survival strategies. Sporangiospores are often thicker-walled, providing greater resistance to desiccation and harsh conditions. This makes them ideal for long-term survival in soil or other inhospitable environments. Conidia, while less robust, are produced in vast numbers, increasing the likelihood of at least some spores finding suitable habitats. Their thinner walls allow for quicker germination upon landing in favorable conditions, giving conidia-producing fungi a competitive edge in nutrient-rich environments.

For practical applications, understanding these differences is crucial. In agriculture, conidia-producing fungi like *Trichoderma* are used as biocontrol agents due to their rapid colonization abilities. Sporangiospore-producing fungi, such as *Rhizopus*, are often studied for their role in food spoilage or fermentation processes. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms, recognizing whether a fungus produces sporangiospores or conidia can guide spore collection techniques. For instance, gently tapping a sporangium-bearing structure releases sporangiospores, while conidia are best harvested by cutting conidiophores and allowing spores to settle on a surface.

In summary, while both sporangiospores and conidia are asexual spores, their formation, structure, and ecological roles diverge significantly. Sporangiospores, produced within sporangia, are built for endurance and long-distance dispersal. Conidia, forming directly on hyphae, prioritize rapid reproduction and localized colonization. Recognizing these distinctions not only deepens our understanding of fungal biology but also informs practical applications in fields ranging from agriculture to biotechnology.

Identifying Contamination in Spore Jars: Signs, Solutions, and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Zygospores Formation: Sexual spores result from zygote fusion, encased in thick, protective walls

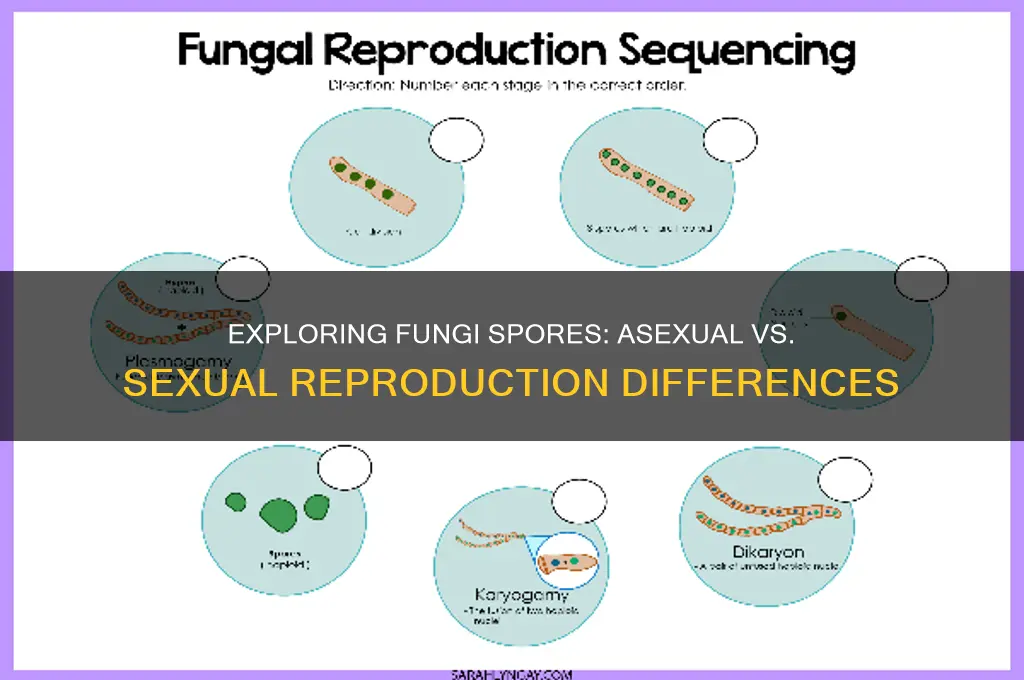

Fungi employ diverse strategies for reproduction, and the formation of zygospores stands out as a fascinating example of sexual spore development. Unlike asexual spores, which are produced by a single parent and genetically identical to it, zygospores arise from the fusion of two compatible haploid gametangia, resulting in a diploid zygote. This process, known as karyogamy, is a hallmark of sexual reproduction in fungi, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability.

The zygospore itself is a marvel of nature’s engineering. Encased in a thick, protective wall, it is designed to withstand harsh environmental conditions, such as drought, extreme temperatures, and predation. This wall, composed of complex polymers like chitin and melanin, acts as a shield, preserving the genetic material within until conditions become favorable for germination. For instance, in the phylum Zygomycota, zygospores can remain dormant for years, only to sprout when moisture and nutrients return to their environment.

Understanding zygospore formation is crucial for both ecological and applied sciences. Ecologically, zygospores contribute to fungal survival in fluctuating environments, playing a key role in nutrient cycling and ecosystem resilience. Practically, this knowledge aids in controlling fungal pathogens in agriculture, as disrupting zygospore formation could limit the spread of diseases like *Rhizopus stolonifer*, a common post-harvest rot of fruits and vegetables.

To observe zygospore formation, one can conduct a simple laboratory experiment using *Rhizopus* species. Inoculate a potato dextrose agar plate with two compatible strains, ensure they grow toward each other, and observe under a microscope for the development of zygosporangia. This hands-on approach not only illustrates the process but also highlights the importance of compatibility in sexual reproduction.

In summary, zygospores exemplify the ingenuity of fungal sexual reproduction, combining genetic recombination with robust protective mechanisms. Their study offers insights into fungal biology, ecological dynamics, and practical applications, making them a compelling focus within the broader topic of fungal spore differentiation.

Are Spore Servers Still Alive? Exploring the Current State

You may want to see also

Ascospores and Basidiospores: Sexual spores formed in asci or on basidia, respectively, via meiosis

Fungi produce spores as part of their reproductive strategies, with ascospores and basidiospores representing two distinct types of sexual spores formed through meiosis. These spores are not just products of fungal reproduction but are also key to understanding fungal diversity and ecological roles. Ascospores develop within sac-like structures called asci, typically found in fungi belonging to the Ascomycota phylum, such as yeasts, morels, and truffles. In contrast, basidiospores are borne on club-shaped structures called basidia, characteristic of the Basidiomycota phylum, which includes mushrooms, puffballs, and rusts.

The formation of ascospores and basidiospores begins with the fusion of haploid cells during sexual reproduction, followed by meiosis, which ensures genetic diversity. Asci typically contain eight ascospores, arranged linearly or in other patterns depending on the species. For example, in *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast), asci are often observed under a microscope as elongated structures with neatly packaged spores. Basidia, on the other hand, usually bear four basidiospores, one at the end of each sterigma, a slender projection extending from the basidium. This arrangement is evident in the gills of mushrooms like *Agaricus bisporus* (button mushroom), where basidiospores are released into the air for dispersal.

Practical observation of these spores can be achieved through simple laboratory techniques. To examine ascospores, prepare a wet mount of fungal tissue (e.g., from an ascocarp) on a microscope slide, add a drop of distilled water, and cover with a coverslip. For basidiospores, collect spores by placing a mature mushroom cap gill-side down on a piece of paper overnight. The resulting spore print can be examined under a microscope or used for identification. Both methods highlight the structural differences between these sexual spores, emphasizing their adaptive significance.

From an ecological perspective, ascospores and basidiospores play distinct roles in fungal survival and dispersal. Ascospores are often more resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions such as drought or extreme temperatures, making them ideal for long-distance dispersal. For instance, *Aspergillus* species, known for producing ascospores, are ubiquitous in soil and decaying matter. Basidiospores, while less hardy, are produced in vast quantities, ensuring successful colonization of new habitats. This is evident in the rapid spread of mushroom mycelium in forests, where billions of basidiospores are released daily.

In conclusion, ascospores and basidiospores exemplify the diversity of fungal reproductive strategies. Their formation via meiosis ensures genetic variation, while their structural and ecological differences reflect adaptations to specific environments. Whether studying fungi in a laboratory or observing them in nature, understanding these spores provides valuable insights into the biology and ecology of fungi. Practical tips for observation, such as wet mounts and spore prints, make this knowledge accessible to both researchers and enthusiasts alike.

Do Hepatophyta Plants Release Airborne Spores? Exploring Their Dispersal Methods

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Triggers: Sexual spores often require specific conditions, while asexual spores are more adaptable

Fungi employ diverse reproductive strategies, and the environmental triggers for spore production reflect this adaptability. Sexual spores, the product of genetic recombination, are often the result of specific and precise conditions. For instance, certain fungi require a narrow temperature range, typically between 20°C and 25°C, and a specific humidity level, often above 90%, to initiate sexual reproduction. These conditions are not merely preferences but necessities, as they ensure the successful fusion of compatible hyphae and the subsequent formation of resilient sexual spores, such as asci or basidiospores. This precision in environmental requirements is a trade-off for the genetic diversity that sexual reproduction provides, which can be crucial for long-term survival in changing ecosystems.

In contrast, asexual spores, like conidia or sporangiospores, are produced under a broader range of conditions, showcasing their adaptability. Asexual reproduction in fungi can occur in environments with fluctuating temperatures, from 15°C to 30°C, and humidity levels as low as 70%. This flexibility allows fungi to rapidly colonize new habitats and exploit resources before competitors. For example, *Aspergillus* species can produce conidia within 24–48 hours under favorable conditions, a process that is less dependent on specific environmental cues compared to sexual reproduction. This rapid response to environmental changes highlights the role of asexual spores as a survival mechanism in unpredictable ecosystems.

The distinction in environmental triggers also influences the ecological roles of these spores. Sexual spores, with their stringent requirements, are often produced in response to stress or nutrient depletion, acting as a long-term survival strategy. For instance, some fungi form sclerotia or fruiting bodies only when resources are scarce, ensuring that sexual spores are released when conditions improve. Asexual spores, however, are more opportunistic, allowing fungi to thrive in transient environments, such as decaying organic matter or disturbed soils. This duality ensures that fungi can both persist and proliferate across diverse ecological niches.

Practical implications of these differences are evident in agriculture and biotechnology. Farmers and mycologists can manipulate environmental conditions to control fungal reproduction. For example, maintaining a consistent temperature of 22°C and high humidity can encourage sexual spore formation in mushrooms, enhancing genetic diversity in cultivated strains. Conversely, preventing these conditions can suppress sexual reproduction, reducing the risk of diseases caused by sexually produced spores. Understanding these triggers also aids in the management of fungal pathogens, as asexual spores’ adaptability makes them more likely to cause rapid, widespread infections under favorable conditions.

In conclusion, the environmental triggers for sexual and asexual spore production in fungi underscore their evolutionary strategies. While sexual spores demand precision, asexual spores thrive on flexibility, each fulfilling distinct ecological roles. This knowledge not only deepens our understanding of fungal biology but also provides practical tools for managing fungi in agriculture, medicine, and conservation. By manipulating environmental conditions, we can harness the benefits of both reproductive modes while mitigating their potential drawbacks.

Can Spores Survive Anaerobic Conditions? Exploring Their Resilience and Limits

You may want to see also

Genetic Diversity: Sexual spores increase diversity via recombination; asexual spores clone the parent fungus

Fungi employ two primary strategies for spore production: sexual and asexual reproduction. Each method has distinct implications for genetic diversity, a critical factor in fungal survival and adaptation. Sexual spores, formed through the fusion of gametes from two compatible individuals, introduce genetic recombination. This process shuffles genetic material, creating offspring with unique combinations of traits. In contrast, asexual spores are clones of the parent fungus, carrying identical genetic information. This fundamental difference in reproductive mechanisms directly influences the genetic variability within fungal populations.

Consider the example of *Penicillium*, a genus of fungi known for producing penicillin. When *Penicillium* reproduces sexually, the resulting spores inherit a mix of genetic material from both parents. This genetic diversity can lead to new strains with enhanced abilities, such as improved antibiotic production or resistance to environmental stressors. Conversely, asexual reproduction in *Penicillium* generates spores that are genetically identical to the parent. While this ensures rapid proliferation, it limits the population's ability to adapt to changing conditions, as all offspring share the same vulnerabilities and strengths.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these reproductive strategies is crucial for industries like agriculture and medicine. For instance, fungal pathogens that rely heavily on asexual reproduction, such as *Botrytis cinerea* (gray mold), can devastate crops due to their rapid spread. However, their lack of genetic diversity makes them more susceptible to targeted fungicides. On the other hand, sexually reproducing fungi like *Fusarium* species pose a greater challenge due to their ability to evolve resistance through genetic recombination. Farmers and researchers must therefore tailor their strategies based on the reproductive mode of the fungus in question.

To illustrate the impact of genetic diversity, compare the lifecycles of *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast) and *Aspergillus flavus* (a toxin-producing fungus). *S. cerevisiae* can switch between asexual budding and sexual sporulation, depending on environmental conditions. This flexibility allows it to thrive in diverse settings, from bakeries to breweries. In contrast, *A. flavus* primarily reproduces asexually, producing large numbers of spores that contaminate crops like peanuts and corn. While asexual reproduction enables its rapid spread, the lack of genetic diversity makes it more predictable—and potentially more controllable—than sexually reproducing fungi.

In conclusion, the choice between sexual and asexual spore production is a trade-off between stability and adaptability. Sexual spores drive genetic diversity through recombination, equipping fungal populations to evolve and survive in changing environments. Asexual spores, while efficient for rapid colonization, limit diversity by cloning the parent fungus. For anyone working with fungi—whether in research, agriculture, or industry—recognizing these differences is key to managing fungal populations effectively. By leveraging this knowledge, we can develop strategies that either harness the benefits of genetic diversity or exploit the vulnerabilities of clonal reproduction.

Exploring Fungal Spores' Role in Sexual Reproduction: Unveiling Nature's Secrets

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Asexual spores are produced by a single parent without fertilization, while sexual spores result from the fusion of gametes from two compatible parents.

Asexual spores (e.g., conidia) are typically single-celled and simple in structure, whereas sexual spores (e.g., asci or basidiospores) are often multicellular, more complex, and encased in specialized structures.

Asexual spores allow for rapid reproduction and colonization in favorable conditions, while sexual spores promote genetic diversity and survival in harsh environments through recombination.