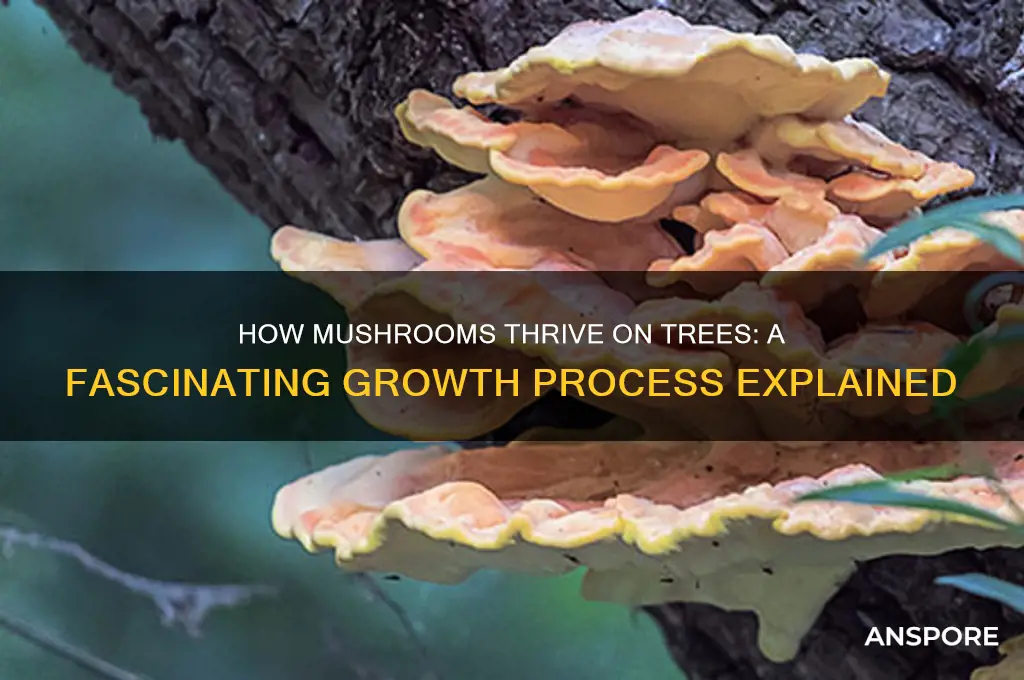

Mushrooms growing on trees, a phenomenon often observed in forests and wooded areas, are the visible fruiting bodies of fungi that form symbiotic or parasitic relationships with their host trees. These fungi typically thrive in damp, shaded environments, where they decompose wood or extract nutrients from living trees. The growth process begins when fungal spores land on a suitable tree and germinate, sending thread-like structures called hyphae into the wood. Over time, these hyphae form a network known as mycelium, which breaks down cellulose and lignin in dead or decaying trees or taps into the resources of living ones. When conditions are right—usually involving sufficient moisture and temperature—the mycelium produces mushrooms as reproductive structures to release spores and continue the life cycle. This process not only highlights the ecological role of fungi in nutrient cycling but also underscores their complex interactions with tree ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Substrate | Dead or decaying wood (trees, logs, stumps) |

| Nutrient Source | Lignin and cellulose in wood |

| Fungi Type | Primarily saprotrophic (decomposers) |

| Growth Form | Fruiting bodies (mushrooms) emerge from mycelium |

| Mycelium Role | Network of thread-like structures that break down wood and absorb nutrients |

| Moisture Requirement | High humidity and moisture are essential for growth |

| Temperature Range | Typically 50°F to 80°F (10°C to 27°C), depending on species |

| Common Species | Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), shiitake (Lentinula edodes), bracket fungi (Ganoderma spp.) |

| Growth Time | Weeks to months, depending on species and conditions |

| Ecological Role | Decomposers, recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem |

| Tree Health Impact | Can indicate decaying wood but do not directly harm healthy trees |

| Harvesting | Mushrooms can be sustainably harvested without damaging the mycelium |

| Cultivation | Often grown on logs or wood chips in controlled environments |

| Seasonality | Typically grow in spring, fall, or after rain, depending on species |

| Symbiotic Relationships | Some mushrooms form mycorrhizal relationships with trees, aiding nutrient exchange |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mushroom spores land on trees, finding ideal conditions like moisture and decaying wood to germinate

- Mycelium colonizes tree bark, breaking down cellulose and lignin for nutrients and growth

- Fruiting bodies emerge, forming mushrooms as the mycelium matures and seeks to reproduce

- Trees provide stability, offering a solid substrate for mushrooms to anchor and develop

- Decay fosters growth, as dead or dying trees create the perfect environment for mushrooms

Mushroom spores land on trees, finding ideal conditions like moisture and decaying wood to germinate

Mushroom spores are microscopic, lightweight, and easily dispersed by wind, animals, or water. When these spores land on trees, they seek out environments that provide the necessary conditions for germination. Trees, especially those with decaying wood or bark, offer an ideal substrate for mushrooms. Decaying wood is rich in organic matter and often retains moisture, creating a perfect habitat for spores to initiate growth. This process begins when a spore lands on a suitable surface and finds the right combination of moisture, temperature, and nutrients.

Moisture is a critical factor for mushroom spores to germinate on trees. Trees in humid environments or those with water-retentive bark provide the necessary dampness for spores to absorb water and activate their metabolic processes. Without adequate moisture, spores remain dormant and unable to develop. Rain, fog, or even high humidity levels can supply the moisture needed for spores to swell and begin the germination process. This is why mushrooms are often found on trees in forested areas with consistent moisture levels.

Decaying wood on trees, often caused by fungi or bacteria breaking down the cellulose and lignin, creates a nutrient-rich environment for mushroom spores. As wood decays, it becomes softer and more porous, allowing spores to penetrate and establish a foothold. The decomposing matter provides essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, which mushrooms need to grow. This symbiotic relationship between mushrooms and decaying wood highlights how trees in various stages of decomposition become prime locations for mushroom colonization.

Once a spore germinates, it develops into a network of thread-like structures called hyphae, which collectively form the mycelium. The mycelium grows through the wood or bark, breaking down organic material and absorbing nutrients. Over time, under the right conditions, the mycelium produces fruiting bodies—the mushrooms we see. This process can take weeks, months, or even years, depending on the species and environmental factors. The presence of decaying wood and consistent moisture ensures the mycelium can thrive and eventually produce spores, continuing the life cycle.

In summary, mushroom spores land on trees and thrive in environments with moisture and decaying wood, which are essential for germination and growth. Moisture activates the spores, while decaying wood provides nutrients and a suitable substrate for the mycelium to develop. This intricate process demonstrates how mushrooms and trees are interconnected in forest ecosystems, with trees providing the resources mushrooms need to flourish. Understanding these conditions not only explains how mushrooms grow on trees but also highlights the importance of decomposing wood in fungal life cycles.

Discovering the Unique Habitats Where Lobster Mushrooms Thrive Naturally

You may want to see also

Mycelium colonizes tree bark, breaking down cellulose and lignin for nutrients and growth

Mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus consisting of a network of fine white filaments called hyphae, plays a crucial role in the growth of mushrooms on trees. This process begins when mycelium colonizes tree bark, often entering through small cracks, wounds, or natural openings. Once established, the mycelium secretes enzymes that break down complex organic compounds present in the bark, such as cellulose and lignin. Cellulose, a structural component of plant cell walls, and lignin, a polymer that provides rigidity to wood, are rich sources of nutrients for the fungus. By decomposing these materials, the mycelium not only extracts essential nutrients but also creates a suitable environment for further growth and development.

The colonization of tree bark by mycelium is a highly efficient process, driven by the fungus's ability to adapt to the woody substrate. As the mycelium spreads, it forms a dense network that penetrates deeper into the bark, increasing its surface area for nutrient absorption. The enzymes secreted by the mycelium, such as cellulases and ligninases, target the strong chemical bonds in cellulose and lignin, breaking them down into simpler sugars and organic acids. These byproducts serve as energy sources for the fungus, fueling its metabolic processes and enabling it to thrive in the tree's environment. This breakdown of woody materials is a key step in the lifecycle of the fungus, as it prepares the foundation for mushroom formation.

The degradation of cellulose and lignin by mycelium not only benefits the fungus but also has ecological implications for the tree and its surroundings. While the fungus gains nutrients, the tree may experience a gradual weakening of its bark and underlying tissues, particularly if it is already stressed or diseased. Over time, this can create cavities or dead zones in the wood, which the mycelium further colonizes. This symbiotic yet potentially parasitic relationship highlights the delicate balance between fungi and their host trees. For the fungus, however, the nutrients derived from cellulose and lignin are vital for energy storage and the eventual production of fruiting bodies—mushrooms.

As the mycelium continues to break down cellulose and lignin, it accumulates resources necessary for mushroom development. When environmental conditions such as moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability are optimal, the mycelium redirects its energy toward forming mushrooms. These fruiting bodies emerge from the colonized bark, often in clusters or singly, as the fungus seeks to disperse its spores. The ability of mycelium to efficiently decompose woody materials is thus directly linked to the successful growth and reproduction of mushrooms on trees. This process underscores the remarkable adaptability and resourcefulness of fungi in utilizing complex organic matter for their survival and proliferation.

In summary, mycelium colonizes tree bark by secreting enzymes that break down cellulose and lignin, extracting nutrients essential for growth and development. This colonization process is fundamental to the lifecycle of mushrooms, as it provides the energy and resources needed for fruiting body formation. While the fungus benefits from this relationship, the tree may experience structural changes or weakening over time. Understanding how mycelium interacts with tree bark and decomposes woody materials offers valuable insights into the ecology of fungi and their role in nutrient cycling within forest ecosystems.

Exploring Pennsylvania's Forests: Do Psychedelic Mushrooms Thrive Here?

You may want to see also

Fruiting bodies emerge, forming mushrooms as the mycelium matures and seeks to reproduce

Mushrooms growing on trees are a fascinating example of nature’s symbiotic relationships, and their development begins with the mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus. Mycelium consists of a network of thread-like structures called hyphae that spread through the tree’s wood, soil, or other substrates. As the mycelium matures, it absorbs nutrients from its environment, often forming a mutualistic relationship with the tree by helping it access water and minerals while receiving carbohydrates in return. This stage is crucial for the fungus’s survival and growth, as it establishes the foundation for reproduction.

When environmental conditions are favorable—such as adequate moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability—the mycelium transitions from its vegetative state to a reproductive phase. This shift triggers the emergence of fruiting bodies, which are the visible structures we recognize as mushrooms. The mycelium redirects its energy toward forming these structures, which serve as the fungus’s reproductive organs. On trees, this often occurs in decaying or dead wood, where the mycelium has already established itself. The fruiting bodies begin as small knots or bumps, known as primordia, which develop on the surface of the tree bark or within the wood.

As the primordia grow, they differentiate into the characteristic mushroom structure: a cap (pileus), gills or pores (hymenium), and a stem (stipe). The gills or pores are particularly important, as they contain spores—the fungus’s reproductive cells. The mycelium’s primary goal in forming these structures is to disperse spores into the environment, ensuring the continuation of the species. The mushroom’s cap often expands and opens up, exposing the gills or pores to the air, which facilitates spore release.

The process of fruiting body formation is highly dependent on the tree’s condition and the environment. Decaying wood provides the ideal substrate, as it is rich in nutrients and has a texture that allows the mycelium to penetrate and grow. Trees with heartwood rot or other fungal infections are common hosts, as the wood’s breakdown creates the perfect conditions for mushroom growth. Additionally, factors like humidity, temperature, and light influence whether the mycelium will initiate fruiting body development.

Once the mushrooms fully mature, they release spores into the surrounding environment, often through wind or water. These spores can travel to new locations, germinate, and grow into new mycelial networks, starting the cycle anew. The fruiting bodies themselves may decompose after spore release, returning nutrients to the ecosystem. This reproductive strategy ensures the fungus’s survival and propagation, even in the challenging environment of a tree’s bark or wood. Thus, the emergence of fruiting bodies is a critical and intricate process in the life cycle of tree-dwelling mushrooms, driven by the mycelium’s maturation and reproductive needs.

Psychedelic Mushrooms in Arizona: Where and How They Grow

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Trees provide stability, offering a solid substrate for mushrooms to anchor and develop

Mushrooms growing on trees are a fascinating example of the symbiotic relationship between fungi and woody plants. Trees provide an ideal environment for mushrooms to thrive, primarily by offering stability and a solid substrate. Unlike soil, which can be loose or prone to erosion, tree bark and wood provide a firm, durable surface for mushrooms to anchor themselves. This stability is crucial for the mushroom’s mycelium—the network of thread-like structures that form the fungus’s body—to grow and spread effectively. The mycelium penetrates the tree’s bark or wood, finding a secure foothold that allows the mushroom to develop and mature without being dislodged by environmental factors like wind or rain.

The structure of trees, with their dense and fibrous wood, creates a robust foundation for mushrooms. As trees age, their bark may develop cracks, crevices, or hollows, which provide additional spaces for mushroom spores to settle and germinate. These natural features act as microhabitats, offering protection and a stable base for the mycelium to colonize. Once established, the mycelium can draw nutrients from the tree, while the mushroom itself benefits from the tree’s elevated position, which aids in spore dispersal. This anchoring process is essential for the mushroom’s lifecycle, ensuring it remains firmly attached to the tree as it grows and releases spores.

Trees also contribute to the stability of mushrooms by providing a consistent and long-lasting substrate. Unlike decaying organic matter on the forest floor, which can decompose quickly, tree wood and bark persist for years, sometimes decades. This longevity allows mushrooms to establish a permanent or semi-permanent presence on the tree, enabling repeated fruiting bodies (the visible mushrooms) to emerge over time. The solid nature of the tree’s structure ensures that the mushroom’s mycelium can continue to grow and expand, even as the tree itself undergoes changes due to aging or environmental stress.

Furthermore, the vertical growth of trees elevates mushrooms above the forest floor, which offers additional advantages. By anchoring to trees, mushrooms gain access to better air circulation and sunlight, both of which are critical for their development. The stability provided by the tree’s trunk or branches ensures that mushrooms are not overshadowed by competing vegetation or buried by leaf litter. This elevated position also aids in spore dispersal, as spores released from tree-dwelling mushrooms can travel farther on air currents, increasing their chances of colonizing new areas.

In summary, trees play a vital role in the growth of mushrooms by providing stability and a solid substrate. Their sturdy bark and wood offer a secure anchoring point for mycelium, while their structural features create ideal microhabitats for spore germination. The longevity of trees ensures a lasting foundation for mushrooms, and their vertical growth enhances the mushrooms’ access to resources and spore dispersal. This relationship highlights how trees serve as more than just a host—they are essential partners in the lifecycle of many mushroom species.

Exploring British Columbia's Forests: Do Magic Mushrooms Thrive Here?

You may want to see also

Decay fosters growth, as dead or dying trees create the perfect environment for mushrooms

Mushrooms growing on trees are a fascinating example of nature’s ability to turn decay into new life. When trees die or begin to decay, their wood becomes a rich substrate for fungi, including mushrooms. This process is driven by the tree’s transition from a living, nutrient-storing organism to a decomposing structure. As the tree’s cellulose and lignin break down, they release nutrients that mushrooms and other fungi can readily absorb. This decomposition is facilitated by enzymes secreted by the fungi, which break down complex organic matter into simpler forms that the mushrooms can use for growth.

Dead or dying trees provide the ideal environment for mushrooms because they offer both physical support and a nutrient-rich medium. The wood’s structure, now weakened and softened, allows mushroom mycelium (the root-like network of fungi) to penetrate and colonize it easily. This mycelium spreads throughout the wood, breaking it down further and extracting essential nutrients like carbon, nitrogen, and minerals. Over time, the mycelium develops fruiting bodies—the mushrooms we see—as a means to reproduce and disperse spores. This symbiotic relationship highlights how decay is not an end but a transformation, fostering new growth in the form of mushrooms.

The role of moisture in this process cannot be overstated. Decay accelerates in damp conditions, which are often present in dead or dying trees due to their inability to regulate water uptake. Mushrooms thrive in these moist environments, as water is essential for their growth and spore dispersal. The tree’s decaying wood acts like a sponge, retaining moisture that supports the fungi’s metabolic processes. This combination of nutrients, structure, and moisture makes dead or dying trees the perfect habitat for mushrooms to flourish.

Beyond providing a physical substrate, decaying trees also reduce competition for resources. In a living tree, nutrients are actively used for growth and defense, leaving little available for fungi. However, in a dead or dying tree, these nutrients become accessible as the tree’s systems shut down. Mushrooms capitalize on this opportunity, rapidly colonizing the wood and converting it into energy for their own growth. This efficiency ensures that no part of the tree goes to waste, as its decay fuels a new cycle of life.

Finally, the presence of mushrooms on decaying trees underscores the importance of fungi in forest ecosystems. By breaking down dead wood, mushrooms and other fungi recycle nutrients back into the soil, supporting the growth of new plants and trees. This process, known as nutrient cycling, is vital for maintaining the health and productivity of forests. Thus, decay fosters growth not only for mushrooms but for the entire ecosystem, demonstrating how even death can be a catalyst for renewal.

Do Lobster Mushrooms Keep Growing? Unveiling Their Unique Life Cycle

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms grow on trees by obtaining nutrients from the wood, often through the help of fungi that decompose dead or decaying tree matter. These fungi form a network called mycelium, which breaks down the wood and allows mushrooms to sprout as fruiting bodies.

No, not all mushrooms that grow on trees are harmful. Some are saprotrophic, meaning they decompose dead wood without harming the living tree. However, parasitic mushrooms can weaken or kill trees by feeding on living tissue.

Mushrooms on trees require moisture, warmth, and a food source (usually dead or decaying wood). Shade and humidity are also favorable conditions, as direct sunlight and dry environments can inhibit growth.

Some mushrooms growing on trees are edible, but many are toxic or inedible. It’s crucial to properly identify the species before consuming them, as misidentification can lead to poisoning or other health risks. Always consult an expert if unsure.