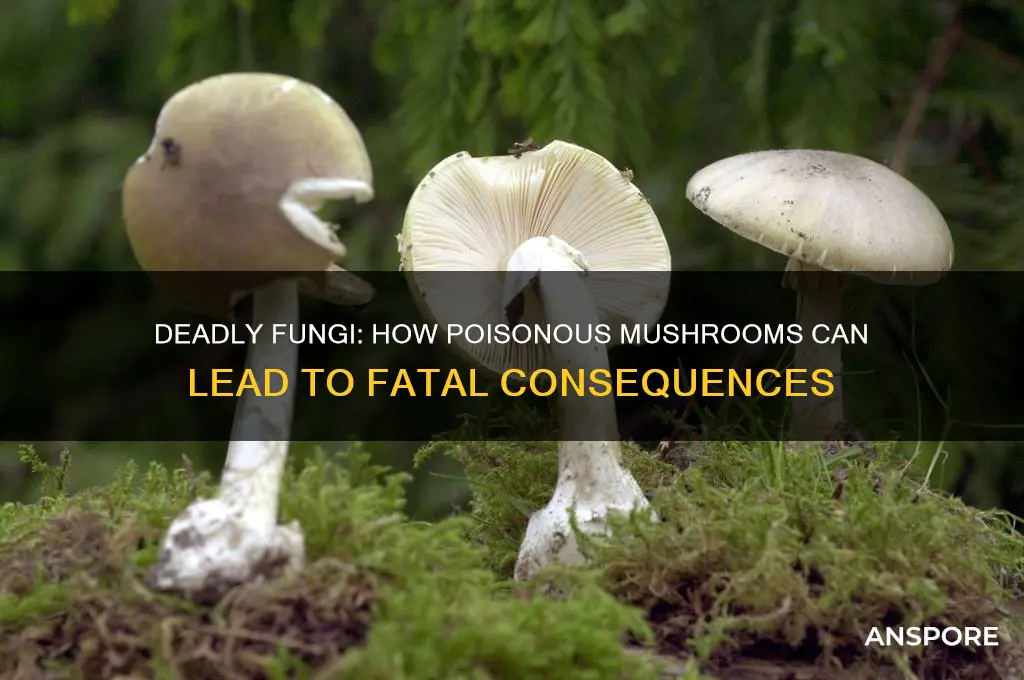

Poisonous mushrooms contain toxins that can cause severe harm or even death when ingested. These toxins vary widely in their effects, ranging from gastrointestinal distress to organ failure, depending on the species of mushroom. For example, the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) produces amatoxins that destroy liver and kidney cells, leading to symptoms like vomiting, diarrhea, and eventually liver failure if left untreated. Other toxic mushrooms, like the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), contain similar deadly compounds. The danger lies in their resemblance to edible varieties, making misidentification a common cause of poisoning. Without prompt medical intervention, including antidotes like activated charcoal or liver transplants in severe cases, the toxins can be fatal, underscoring the importance of caution when foraging wild mushrooms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Toxin Types | Amatoxins, Orellanine, Muscarine, Ibotenic Acid, Coprine, Gyromitrin |

| Mechanism of Action | Amatoxins: Inhibit RNA polymerase II, causing liver and kidney failure. |

| Orellanine: Damages kidney tubules, leading to renal failure. | |

| Muscarine: Stimulates muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, causing cholinergic crisis. | |

| Ibotenic Acid: Acts as a neurotoxin, causing seizures and CNS depression. | |

| Coprine: Interacts with alcohol, causing antabuse-like reactions. | |

| Gyromitrin: Converts to monomethylhydrazine, damaging the liver and CNS. | |

| Symptoms | Gastrointestinal (vomiting, diarrhea), liver failure, kidney failure, neurological symptoms (seizures, confusion), respiratory distress. |

| Onset of Symptoms | 6–24 hours (Amatoxins), 3–4 days (Orellanine), 15–30 minutes (Muscarine). |

| Fatality Rate | Amatoxins: Up to 50% without treatment; Orellanine: High if untreated. |

| Treatment | Activated charcoal, gastric lavage, supportive care, liver transplant (Amatoxins), hemodialysis (Orellanine). |

| Common Poisonous Species | Death Cap (Amanita phalloides), Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera), Fool’s Mushroom (Amanita verna), False Morel (Gyromitra esculenta). |

| Prevention | Avoid foraging without expert knowledge, use field guides, cook thoroughly (note: cooking does not detoxify all toxins). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Toxin Types: Mushrooms contain toxins like amatoxins, orellanine, and muscarine, each attacking different body systems

- Symptoms Timeline: Delayed onset (6-24 hours) masks poisoning, leading to misdiagnosis and delayed treatment

- Liver & Kidney Damage: Amatoxins cause severe liver and kidney failure, often fatal without intervention

- Neurological Effects: Muscarine and ibotenic acid induce seizures, hallucinations, and respiratory paralysis

- Treatment Challenges: No antidote exists; treatment relies on supportive care and sometimes organ transplants

Toxin Types: Mushrooms contain toxins like amatoxins, orellanine, and muscarine, each attacking different body systems

Mushrooms, often celebrated for their culinary versatility, harbor toxins that can silently wage war on the human body. Among these, amatoxins, orellanine, and muscarine stand out as particularly insidious. Each toxin targets distinct physiological systems, turning a seemingly innocuous bite into a potentially fatal encounter. Understanding their mechanisms is crucial for anyone venturing into the world of foraging or simply curious about the darker side of fungi.

Amatoxins, found in the notorious *Amanita* genus (including the "Death Cap" and "Destroying Angel"), are perhaps the most infamous mushroom toxins. These cyclic octapeptides slip past the stomach lining and infiltrate liver and kidney cells, disrupting protein synthesis and causing irreversible damage. Symptoms often appear 6–24 hours after ingestion, starting with vomiting and diarrhea, which can misleadingly suggest a simple stomach bug. However, within 2–3 days, liver failure sets in, often necessitating a transplant for survival. A mere 30 grams of an amatoxin-containing mushroom can be lethal for an adult, making misidentification a grave risk.

Orellanine, present in mushrooms like the "Fool’s Funnel" (*Cortinarius* species), operates with a slower, more deceptive strategy. Unlike amatoxins, its effects aren’t immediately apparent. Orellanine selectively damages kidney tubules, leading to acute renal failure 2–3 days after ingestion. Early symptoms—nausea, thirst, and fatigue—are easily mistaken for dehydration or flu. By the time kidney damage becomes evident, often 3–14 days later, the toxin has already wreaked havoc. There’s no antidote, and treatment relies on dialysis or transplantation. A single meal containing orellanine-rich mushrooms can irreversibly harm the kidneys, underscoring the importance of accurate identification.

Muscarine, named after the *Clitocybe* and *Inocybe* species that produce it, mimics the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, overstimulating the parasympathetic nervous system. Within 15–30 minutes of ingestion, victims experience profuse sweating, salivation, tear production, and blurred vision—a condition known as "SLUDGE" (salivation, lacrimation, urination, defecation, gastrointestinal distress, and emesis). While rarely fatal in small doses, severe cases can lead to respiratory failure. Unlike amatoxin or orellanine poisoning, muscarine’s effects are short-lived, typically resolving within 24 hours. However, its rapid onset demands immediate medical attention to manage symptoms and prevent complications.

Each toxin exemplifies the precision with which mushrooms can disrupt human biology. Amatoxins target vital organs, orellanine stealthily destroys kidneys, and muscarine hijacks the nervous system. For foragers, the lesson is clear: certainty in identification isn’t just a skill—it’s a survival tactic. When in doubt, consult an expert or avoid consumption altogether. After all, the line between a gourmet meal and a toxic encounter is often thinner than the gills of a mushroom.

Are Smoking Mushrooms Poisonous? Unveiling the Risks and Truth

You may want to see also

Symptoms Timeline: Delayed onset (6-24 hours) masks poisoning, leading to misdiagnosis and delayed treatment

The insidious nature of many poisonous mushrooms lies in their delayed onset of symptoms, which can range from 6 to 24 hours after ingestion. This lag creates a dangerous window where victims may feel perfectly fine, unaware of the toxic compounds already wreaking havoc within their bodies. During this time, the toxins—often amatoxins in the case of *Amanita* species—quietly infiltrate liver and kidney cells, causing irreversible damage before the first symptom appears. This delay is not just a biological quirk; it’s a critical factor that complicates diagnosis and treatment, often with fatal consequences.

Consider the case of a hiker who forages a mushroom resembling a chanterelle but unknowingly consumes the deadly *Amanita phalloides*. Within 6 to 24 hours, they may experience nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea—symptoms easily mistaken for food poisoning or a stomach virus. By the time organ failure sets in, typically 24 to 48 hours later, the toxin has already done irreparable harm. This timeline is particularly treacherous because it lulls both the victim and healthcare providers into a false sense of security, delaying the urgent medical intervention required to flush the toxin from the system or support failing organs.

The delayed onset also complicates treatment protocols. For instance, silibinin, a compound used to counteract amatoxin poisoning, is most effective when administered within hours of ingestion. However, by the time symptoms appear and a diagnosis is confirmed, the toxin has often progressed beyond the point where such treatments can be fully effective. This underscores the importance of immediate medical attention if mushroom poisoning is even suspected, even in the absence of symptoms. A critical step is to preserve a sample of the consumed mushroom for identification, as this can expedite treatment and improve outcomes.

To mitigate the risks, it’s essential to adopt a proactive approach. Avoid foraging for mushrooms unless you are an experienced mycologist or accompanied by one. If ingestion occurs, do not wait for symptoms to appear. Contact a poison control center or seek emergency medical care immediately, providing as much detail as possible about the mushroom consumed. Time is of the essence, and acting swiftly can mean the difference between a full recovery and irreversible organ damage or death. The delayed onset of symptoms is not just a feature of poisonous mushrooms—it’s a ticking clock that demands immediate action.

How Poisonous Mushrooms Affect the Nervous System: Risks and Symptoms

You may want to see also

Liver & Kidney Damage: Amatoxins cause severe liver and kidney failure, often fatal without intervention

Amatoxins, a group of cyclic octapeptides found in certain poisonous mushrooms like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), are silent assassins. Ingesting as little as half a mushroom can deliver a lethal dose, with symptoms often delayed by 6–24 hours, lulling victims into a false sense of security. These toxins slip past the digestive system unscathed, entering the bloodstream and targeting the liver and kidneys with ruthless efficiency.

The mechanism is insidious. Amatoxins bind to RNA polymerase II, a critical enzyme for protein synthesis, effectively shutting down cellular function in hepatocytes (liver cells) and nephrons (kidney units). Within 24–48 hours, the liver begins to necrotize, releasing enzymes like AST and ALT into the bloodstream, while the kidneys, overwhelmed by toxin filtration, lose their ability to clear waste. This dual-organ assault triggers a cascade of symptoms: jaundice, coagulopathy, oliguria, and eventually, multi-organ failure. Without urgent medical intervention—typically intravenous silibinin, N-acetylcysteine, and hemodialysis—mortality rates soar to 50–90%, depending on the delay in treatment.

Consider this stark reality: a family in Oregon mistakenly cooked Death Caps into a stew, believing them to be edible Paddy Straw mushrooms. Within 48 hours, three adults exhibited acute liver failure, requiring emergency liver transplants. The youngest, a 12-year-old, survived due to prompt hospitalization, but the delay in recognizing symptoms nearly proved fatal. This case underscores the importance of immediate action: induced vomiting (if ingestion is recent), activated charcoal administration, and urgent transfer to a medical facility equipped to monitor liver and kidney enzymes.

Prevention is paramount. Foraging without expertise is a gamble; even seasoned mycologists cross-reference specimens with spore prints and microscopic features. A single misidentification can be catastrophic. Practical tips include: avoid mushrooms with white gills and a bulbous base, carry a field guide, and never consume wild fungi without verification by a certified expert. In regions like California, where Death Caps thrive in oak woodlands, public health campaigns emphasize the adage, "There are old foragers, and there are bold foragers, but there are no old, bold foragers."

The takeaway is clear: amatoxin poisoning is a race against time. Recognize the symptoms—gastrointestinal distress followed by jaundice and reduced urine output—and act decisively. Hospitals must be prepared to initiate liver support therapy and renal replacement therapy, often in tandem. Survival hinges on swift diagnosis and aggressive treatment, making awareness and education the first line of defense against these deceptively innocuous fungi.

Are Bella Mushrooms Poisonous to Cats? A Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$15.8 $17.99

Neurological Effects: Muscarine and ibotenic acid induce seizures, hallucinations, and respiratory paralysis

Mushrooms containing muscarine and ibotenic acid pose a significant threat by targeting the nervous system, leading to a cascade of life-threatening symptoms. These toxins, found in species like *Clitocybe dealbata* (muscarine) and *Amanita muscaria* (ibotenic acid), act as chemical saboteurs, disrupting normal neurological function. Muscarine mimics the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, overstimulating muscarinic receptors and causing symptoms such as excessive sweating, salivation, and bronchial secretions. Ibotenic acid, on the other hand, excites glutamate receptors, leading to seizures, hallucinations, and disorientation. Together, these toxins create a dangerous synergy, overwhelming the body’s ability to regulate vital functions.

Consider the scenario of accidental ingestion: a hiker misidentifies *Amanita muscaria* as an edible species and consumes a moderate amount. Within 30 minutes to 2 hours, symptoms emerge. The initial signs—nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea—may seem like typical food poisoning. However, as muscarine and ibotenic acid take hold, the individual may experience muscle twitches, confusion, and visual distortions. In severe cases, seizures can occur, followed by respiratory paralysis as the diaphragm muscles fail to contract. The progression is rapid, and without immediate medical intervention, the outcome can be fatal.

To mitigate the risks, it’s crucial to understand dosage thresholds. Muscarine toxicity typically occurs at doses as low as 0.1–0.5 mg/kg body weight, while ibotenic acid’s effects are noticeable at 1–2 mg/kg. For a 70 kg adult, this translates to just 7–35 mg of muscarine or 70–140 mg of ibotenic acid. Children are particularly vulnerable due to their lower body weight, making even small amounts of these toxins potentially lethal. Always exercise extreme caution when foraging and rely on expert identification or commercially sourced mushrooms.

Practical tips can save lives. If exposure is suspected, immediate steps include inducing vomiting (if the person is conscious) and administering activated charcoal to bind toxins in the digestive tract. Seek emergency medical care promptly, as atropine—an antidote for muscarine poisoning—can counteract cholinergic symptoms. For ibotenic acid, benzodiazepines may control seizures, and respiratory support is critical in cases of paralysis. Education and preparedness are key: familiarize yourself with toxic mushroom species in your region and carry a field guide or app for reference.

In comparison to other mushroom toxins like amatoxins, which cause liver failure, muscarine and ibotenic acid act faster but offer a better prognosis if treated early. Amatoxin poisoning often presents with a latency period of 6–24 hours, whereas muscarine and ibotenic acid symptoms appear within hours. This rapid onset, while alarming, provides a narrow window for intervention. By recognizing the neurological effects of these toxins and responding swiftly, individuals can significantly improve survival outcomes. Always remember: when in doubt, throw it out.

Are Elephant Ear Mushrooms Poisonous? A Comprehensive Guide to Safety

You may want to see also

Treatment Challenges: No antidote exists; treatment relies on supportive care and sometimes organ transplants

Poisonous mushrooms contain toxins that can cause severe, sometimes irreversible damage to vital organs. Unlike many other forms of poisoning, there is no universal antidote for mushroom toxicity. This absence of a specific cure leaves medical professionals with limited options, primarily relying on supportive care to stabilize the patient while their body attempts to eliminate the toxin. For instance, activated charcoal may be administered early to bind the toxin in the gastrointestinal tract, but its effectiveness diminishes rapidly after ingestion. Beyond this, treatment becomes a race against time, as the toxin continues to wreak havoc on organs like the liver, kidneys, or nervous system.

Supportive care in mushroom poisoning is tailored to the specific symptoms and organ systems affected. For example, amatoxin-containing mushrooms, such as the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), cause severe liver damage within 24–48 hours. Patients may require intravenous fluids to maintain hydration, electrolyte balance, and blood pressure. In cases of kidney failure, dialysis becomes necessary to filter waste products from the blood. For neurological symptoms, such as seizures or confusion, medications like benzodiazepines or anticonvulsants may be used. However, these measures are reactive, addressing symptoms rather than the root cause, underscoring the critical need for early intervention.

The severity of mushroom poisoning often necessitates drastic measures, such as organ transplantation, particularly for liver failure. Amatoxin poisoning, for instance, can lead to fulminant hepatic failure within 5–7 days, leaving transplantation as the only viable option for survival. This procedure, however, is not without risks, including rejection, infection, and lifelong immunosuppression. The decision to transplant is further complicated by the limited availability of donor organs and the urgency of the patient’s condition. For example, a study published in *Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology* found that 40% of patients with amatoxin-induced liver failure required a liver transplant, with a 90-day survival rate of 83% post-transplant.

Despite advances in medical care, the lack of an antidote remains a significant challenge in treating mushroom poisoning. Prevention, therefore, becomes paramount. Educating the public about the risks of foraging wild mushrooms and emphasizing the importance of proper identification are critical steps. For those who suspect ingestion of a poisonous mushroom, immediate medical attention is essential. Bringing a sample of the mushroom for identification can aid in diagnosis and treatment planning. While supportive care and organ transplantation offer hope, they are not guarantees of survival, making avoidance the most effective strategy. In the absence of a cure, awareness and caution are the best defenses against the silent danger of toxic mushrooms.

Are Paleonia's Brown Mushrooms Poisonous? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Poisonous mushrooms contain toxins that can damage vital organs, disrupt bodily functions, or cause severe poisoning, often leading to organ failure, respiratory distress, or death.

Common toxins include amatoxins (found in *Amanita* species), which destroy liver and kidney cells, and orellanine (found in *Cortinarius* species), which causes kidney failure.

Symptoms can appear anywhere from 20 minutes to 24 hours after ingestion, depending on the toxin. Delayed symptoms are often more dangerous, as they may indicate severe organ damage.

No, cooking, boiling, or drying does not eliminate mushroom toxins. Most toxins are heat-stable and remain harmful even after preparation.