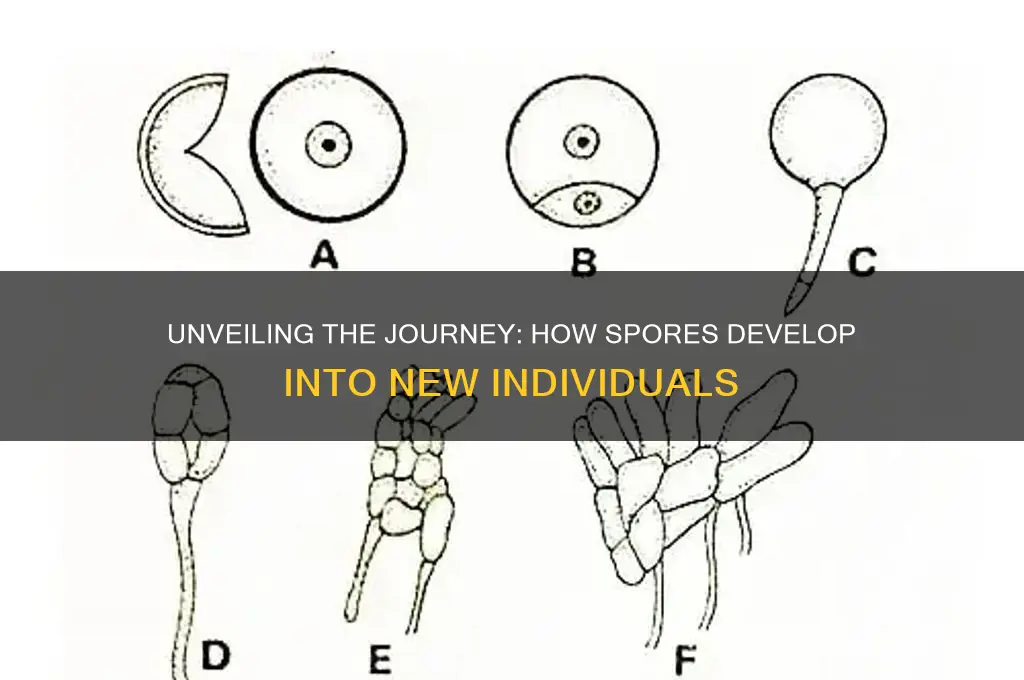

Spores are specialized reproductive structures produced by plants, fungi, and some microorganisms, serving as a crucial mechanism for survival and dispersal. In the development of new individuals, spores undergo a process known as germination, which is triggered by favorable environmental conditions such as moisture, temperature, and light. Upon germination, the spore's protective outer layer ruptures, allowing the emergence of a small, multicellular structure called a sporeling or germ tube. This initial growth stage is characterized by rapid cell division and differentiation, as the sporeling develops into a juvenile form of the organism. In fungi, for example, the germ tube elongates and branches, eventually forming a network of filaments called hyphae, which collectively constitute the mycelium. Similarly, in plants like ferns and mosses, the sporeling gives rise to a gametophyte, a haploid structure that produces gametes for sexual reproduction. As the new individual matures, it develops the necessary organs or structures for photosynthesis, nutrient absorption, and reproduction, ultimately ensuring the continuation of the species through the production of the next generation of spores.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spores Formation | Spores are produced by parent organisms through asexual or sexual reproduction, often in specialized structures like sporangia. |

| Dormancy | Spores enter a dormant state, allowing them to survive harsh conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, or lack of nutrients. |

| Dispersal | Spores are dispersed via wind, water, animals, or other mechanisms to reach new environments. |

| Germination | Upon landing in a suitable environment, spores absorb water, activating metabolic processes and initiating growth. |

| Cell Division | The spore undergoes cell division (mitosis) to form a multicellular structure, such as a protonema (in plants) or a germ tube (in fungi). |

| Development | The emerging structure develops into a new individual, either directly (e.g., fungi, algae) or indirectly (e.g., plants via gametophytes). |

| Environmental Requirements | Spores require specific conditions like moisture, temperature, light, and nutrients to germinate and grow. |

| Genetic Variation | In sexually produced spores, genetic recombination occurs, introducing diversity in the new individuals. |

| Survival Strategy | Spores serve as a survival mechanism, enabling organisms to persist in unfavorable conditions and colonize new habitats. |

| Examples | Fungi (e.g., molds, mushrooms), plants (e.g., ferns, mosses), bacteria (e.g., endospores), and some protists. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores Germination: Activation of dormant spores under favorable conditions triggers growth

- Hyphal Growth: Spores develop filamentous structures for nutrient absorption and expansion

- Cell Division: Spores undergo mitosis to multiply and form multicellular structures

- Differentiation: Cells specialize into distinct tissues or organs for function

- Maturation: Fully developed individuals become capable of producing new spores

Spores Germination: Activation of dormant spores under favorable conditions triggers growth

Spores, the resilient survival units of various organisms, remain dormant until conditions align for growth. This dormancy is a strategic adaptation, allowing them to withstand harsh environments such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, or nutrient scarcity. Once favorable conditions—adequate moisture, suitable temperature, and nutrient availability—are detected, spores activate metabolic processes that initiate germination. For instance, fungal spores require water absorption to rehydrate their cellular machinery, while bacterial endospores need specific nutrients and warmth to break their protective coats. This activation is not random but a precise response to environmental cues, ensuring survival and proliferation when resources are optimal.

The germination process begins with the spore’s outer layer softening or rupturing, enabling water and nutrients to enter. In fungi, this involves the isotropic growth of the spore wall, followed by the emergence of a germ tube—a structure that anchors the spore and absorbs resources. For bacterial endospores, germination is a multi-step process triggered by specific nutrients like amino acids or sugars. For example, *Bacillus subtilis* endospores require L-valine and a germinant receptor to initiate coat degradation and core rehydration. This phase is critical, as incomplete germination can lead to spore death, underscoring the importance of precise environmental conditions.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore germination is vital in fields like agriculture, food preservation, and medicine. Farmers can manipulate soil moisture and temperature to control fungal spore germination, reducing crop diseases. In food science, preventing spore germination of *Clostridium botulinum* in canned goods is achieved by high-temperature processing (121°C for 3 minutes) to destroy spores and inhibit growth. Conversely, horticulture leverages controlled germination of fern or orchid spores in sterile media with specific humidity (80-90%) and light conditions to propagate rare species. These applications highlight the dual nature of spore germination—a threat when uncontrolled, but a tool when harnessed.

Comparatively, spore germination across species reveals both commonalities and unique adaptations. While fungal and bacterial spores share the need for water and nutrients, their mechanisms differ. Fungal spores rely on polar growth and hyphal extension, whereas bacterial endospores undergo core activation and outgrowth. Plant spores, such as those of mosses, require light cues for germination, a feature absent in microbial spores. This diversity reflects evolutionary tailoring to specific environments, yet all converge on the principle of dormancy breaking under favorable conditions. Such comparisons not only deepen scientific understanding but also inspire biomimetic solutions, like designing resilient materials or targeted drug delivery systems.

In conclusion, spore germination is a finely tuned process that bridges dormancy and growth, driven by environmental signals and species-specific mechanisms. Its study offers practical insights for industries and reveals nature’s ingenuity in survival strategies. Whether combating pathogens or cultivating biodiversity, mastering this process empowers us to manipulate life’s smallest units for macro-level impact.

Understanding Mold Spores: How Common Are They in Our Environment?

You may want to see also

Hyphal Growth: Spores develop filamentous structures for nutrient absorption and expansion

Spores, those microscopic survival pods of the fungal world, don't simply sprout legs and walk away. Their journey to becoming new individuals is a fascinating tale of filamentous ingenuity. Hyphal growth, the development of thread-like structures called hyphae, is the key to their success. Imagine a tiny, dormant spore awakening in a nutrient-rich environment. Its first act is to germinate, sending out a delicate hyphal strand, a microscopic explorer seeking sustenance.

This initial hypha, driven by the spore's stored energy, elongates and branches, forming a network akin to a subterranean root system. This network, the mycelium, becomes the fungus's feeding ground, absorbing water, minerals, and organic matter essential for growth.

Think of hyphae as the fungal equivalent of a highly efficient delivery system. Their slender structure maximizes surface area, allowing for optimal nutrient uptake. Unlike plants with their bulky roots, hyphae can penetrate tiny crevices and exploit even the most inaccessible food sources. This adaptability is crucial for fungi, which often thrive in environments where nutrients are scarce or unevenly distributed.

Unlike animals that actively hunt for food, fungi rely on this passive absorption, a strategy made possible by the expansive reach of their hyphal network.

The beauty of hyphal growth lies in its dual purpose. While primarily focused on nutrient acquisition, the expanding mycelium also serves as the foundation for the fungus's physical structure. As the network grows, it can give rise to specialized structures like fruiting bodies (mushrooms, for example) that produce and disperse new spores, completing the life cycle. This dual functionality showcases the elegance of fungal biology, where survival and reproduction are intricately intertwined within the very fabric of their growth.

Understanding hyphal growth has practical implications beyond marveling at fungal ingenuity. It's crucial in fields like agriculture, where mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, enhancing nutrient uptake and plant health. By harnessing the power of hyphal networks, we can develop sustainable agricultural practices and potentially engineer solutions for nutrient-depleted soils. The study of hyphal growth isn't just about understanding fungi; it's about unlocking a world of possibilities for a more sustainable future.

Identifying Mold Spores in Your Home: Signs, Risks, and Solutions

You may want to see also

Cell Division: Spores undergo mitosis to multiply and form multicellular structures

Spores, often likened to the seeds of the microbial world, hold the remarkable ability to develop into new individuals under favorable conditions. Central to this process is cell division, specifically mitosis, which allows spores to multiply and form multicellular structures. Unlike sexual reproduction, which involves the fusion of gametes, spore development relies on a single parent cell, making it a highly efficient mechanism for propagation in fungi, plants, and some protozoa. This asexual method ensures genetic consistency, enabling rapid colonization of new environments.

To understand how spores leverage mitosis, consider the lifecycle of a fern. When a fern spore lands in a suitable habitat, it absorbs water and nutrients, triggering germination. The spore then undergoes mitosis, a process where the nucleus divides, producing two identical daughter cells. This division repeats, leading to the formation of a multicellular structure called a prothallus. The prothallus, though small, is a critical stage in the fern’s lifecycle, as it houses reproductive organs that eventually give rise to the next generation of ferns. This example illustrates how mitosis in spores serves as the foundation for complex multicellular development.

Mitosis in spores is not merely a replication process but a tightly regulated sequence of events. During prophase, the nuclear membrane dissolves, and chromosomes condense, ensuring accurate distribution to daughter cells. Metaphase aligns chromosomes at the cell’s equator, while anaphase separates them into identical sets. Telophase concludes the division, reforming the nuclear membrane and preparing the cell for the next cycle. This precision is vital, as errors in mitosis can lead to mutations or cell death, jeopardizing the spore’s ability to develop into a viable organism.

Practical applications of spore mitosis extend beyond biology classrooms. In agriculture, understanding this process aids in the cultivation of spore-producing crops like mushrooms. For instance, mushroom farmers optimize humidity and temperature to encourage spore germination and mitosis, ensuring robust mycelium growth. Similarly, in biotechnology, spores of bacteria like *Bacillus subtilis* are engineered to produce enzymes or vaccines through controlled mitotic division. By manipulating the conditions that trigger spore activation, scientists can harness this natural process for industrial and medical purposes.

In conclusion, the role of mitosis in spore development is a testament to the elegance of cellular mechanisms. From ferns to fungi, this process enables spores to transition from dormant, single-celled entities into thriving multicellular organisms. Whether in nature or the lab, mastering the intricacies of spore mitosis opens doors to innovations in agriculture, medicine, and beyond. By focusing on this specific aspect of spore development, we gain a deeper appreciation for the fundamental processes that drive life’s diversity.

Dandelion Puffballs: Unveiling the Truth About Their Spores and Seeds

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Differentiation: Cells specialize into distinct tissues or organs for function

Spores, whether from fungi, plants, or certain bacteria, begin as dormant, resilient structures capable of surviving harsh conditions. Once activated by favorable environments—moisture, warmth, or nutrients—they germinate, initiating a transformation from a single cell into a complex organism. This process hinges on differentiation, where cells specialize into distinct tissues or organs, each tailored for specific functions. Without this critical step, spores would remain rudimentary, unable to develop into mature individuals.

Consider the fungal spore as a case study. Upon germination, the spore’s nucleus divides, and cells elongate to form a hyphal network. Initially, these cells are undifferentiated, but as growth progresses, they respond to internal and external cues. Some cells thicken their walls to provide structural support, becoming part of the stalk. Others develop into spore-producing structures, such as the gills of a mushroom. This specialization is not random; it’s orchestrated by genetic programs and environmental signals, ensuring each cell type contributes uniquely to the organism’s survival.

In plants, spore differentiation is equally fascinating. Fern spores, for instance, develop into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure. Cells at one end differentiate into sperm-producing antheridia, while those at the other end form egg-producing archegonia. This division of labor is essential for sexual reproduction. Without such specialization, the gametophyte would lack the ability to propagate the species. The process is so precise that even slight disruptions in nutrient availability or light exposure can alter cell fate, highlighting the delicate balance required for differentiation.

To observe differentiation in action, try cultivating mold on a damp bread slice. Within days, you’ll notice the transition from uniform hyphae to specialized structures like sporangia, which release new spores. This simple experiment underscores the dynamic nature of cell specialization. For educators or hobbyists, documenting this process with time-lapse photography can provide a vivid illustration of how individual cells collaborate to form functional tissues and organs.

In essence, differentiation is the linchpin of spore development, transforming a solitary cell into a multifaceted organism. By studying this process, we gain insights into the fundamental mechanisms of life—how simplicity evolves into complexity, and how cells, through specialization, create systems greater than the sum of their parts. Whether in fungi, plants, or other spore-producing organisms, this principle remains universal, a testament to the elegance of biological design.

Mycotoxins vs. Spores: Understanding the Key Differences and Risks

You may want to see also

Maturation: Fully developed individuals become capable of producing new spores

Spores, the resilient survival units of various organisms, undergo a transformative journey to become fully developed individuals capable of perpetuating their species. This maturation process is a critical phase where the organism transitions from a dormant, resilient state to a reproductive powerhouse. In fungi, for instance, the spore germinates under favorable conditions, growing into a hyphal network that eventually forms a mature fungus. Similarly, in ferns, spores develop into gametophytes, which then produce sex organs to initiate the next generation. This maturation is not merely growth but a complex series of physiological and structural changes that enable spore-producing capability.

Consider the lifecycle of a mushroom, a prime example of spore maturation. Once a spore lands in a suitable environment, it absorbs water and nutrients, initiating germination. The emerging hyphae intertwine to form a mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus. As the mycelium matures, it accumulates energy reserves and responds to environmental cues like humidity and temperature. Under optimal conditions, the mycelium develops fruiting bodies—mushrooms—which house the spore-producing structures (basidia or asci). This maturation process typically takes weeks to months, depending on species and environmental factors. For cultivators, maintaining a consistent temperature (20–25°C) and humidity (80–90%) accelerates maturation, ensuring robust spore production.

The maturation phase is not without challenges. In plants like ferns, the gametophyte stage is highly vulnerable to desiccation and predation. To mitigate risks, gardeners often use a peat-based substrate and mist the environment regularly to maintain moisture. For fungal spores, contamination by competing microorganisms can halt maturation. Sterilizing growth mediums with a 10% bleach solution or autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes is a proven method to ensure a clean environment. These precautions highlight the delicate balance required for successful maturation, emphasizing the need for precision in both natural and controlled settings.

Comparatively, bacterial endospores offer a unique perspective on maturation. Unlike fungal or plant spores, endospores are not reproductive units but survival structures. However, the maturation of the bacterium itself into a spore-producing state is equally fascinating. For *Bacillus subtilis*, nutrient depletion triggers sporulation, a process lasting 6–8 hours under lab conditions. Researchers often use defined media with specific nutrient concentrations (e.g., 0.5% glucose, 0.2% ammonium) to study this process. This example underscores how maturation is universally driven by environmental cues, though the outcomes—reproduction versus survival—vary across species.

In practical terms, understanding maturation is crucial for applications like agriculture, medicine, and conservation. For instance, mycologists cultivate edible mushrooms by optimizing maturation conditions, while botanists propagate rare ferns by nurturing gametophytes. In biotechnology, spore-producing bacteria are harnessed for enzyme production or bioremediation. A key takeaway is that maturation is not a passive process but a dynamic response to environmental signals, requiring specific conditions to unlock reproductive potential. Whether in a forest, lab, or garden, mastering these conditions ensures the continuity of spore-based life cycles.

Christmas Trees and Mold: Uncovering Hidden Spores in Your Holiday Decor

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are microscopic, single-celled reproductive units produced by plants, fungi, and some microorganisms. They develop into new individuals through germination, where they absorb water, activate metabolic processes, and grow into a multicellular organism, such as a fungus, fern, or bacterium.

Spores require specific environmental conditions to develop, including adequate moisture, suitable temperature, and a nutrient-rich substrate. Light, oxygen, and pH levels may also play a role, depending on the species.

Spores are typically haploid and develop directly into a new individual without fertilization, whereas seeds are diploid and result from the fusion of gametes (fertilization) in seed-bearing plants. Spores are also generally smaller and more resilient to harsh conditions than seeds.

Yes, spores can develop into new individuals independently, as they are self-contained reproductive units. Once dispersed, they can germinate and grow in suitable environments, even in the absence of a parent organism. This allows them to colonize new areas efficiently.