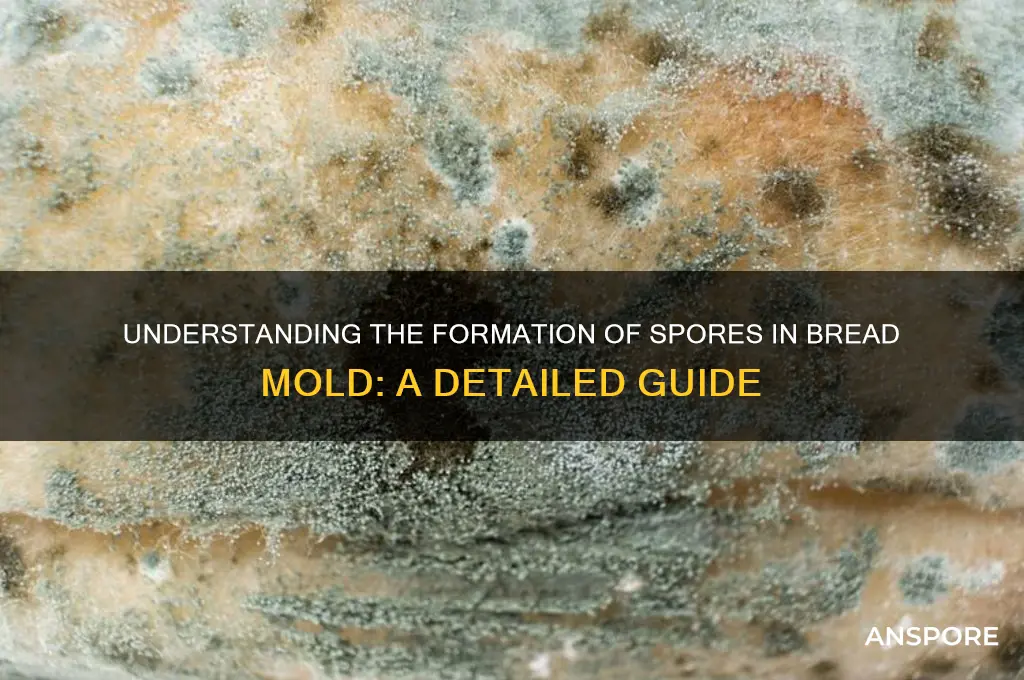

Bread mold, a common fungus often seen as fuzzy growth on stale bread, reproduces through the formation of spores, which are microscopic, resilient structures designed for survival and dispersal. Spores develop as part of the mold's life cycle, typically forming on specialized structures called sporangia or conidiophores, depending on the species. Under favorable conditions, such as warmth and moisture, the mold's hyphae (thread-like structures) grow and branch out, eventually producing these spore-bearing structures. Once mature, the spores are released into the environment, where they can remain dormant until conditions are suitable for germination, allowing the mold to colonize new food sources and continue its life cycle. This process highlights the adaptability and efficiency of bread mold in spreading and thriving in various environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Sporulation Process | Asexual reproduction method in bread mold (e.g., Rhizopus stolonifer) |

| Trigger Conditions | Nutrient depletion, environmental stress, or aging of mycelium |

| Structure Formation | Sporangiophores (specialized hyphae) develop from the mycelium |

| Spore Production Site | Sporangia (sac-like structures) form at the tips of sporangiophores |

| Spore Type | Sporangiospores (haploid, single-celled, and lightweight) |

| Maturation | Sporangia mature, turning dark in color (e.g., black or gray) |

| Release Mechanism | Sporangia rupture, releasing spores into the air |

| Dispersal | Spores are dispersed by air currents, insects, or physical contact |

| Survival Strategy | Spores are highly resistant to harsh conditions (e.g., desiccation, heat) |

| Germination | Spores germinate upon landing in a suitable environment (e.g., moist bread) |

| Ecological Role | Ensures survival and propagation of the mold in adverse conditions |

| Timeframe | Sporulation typically occurs within 24–48 hours under optimal conditions |

| Environmental Factors | High humidity, warmth (25–30°C), and lack of nutrients promote sporulation |

| Genetic Regulation | Controlled by specific genes and signaling pathways in the mold |

| Visual Identification | Visible as dark, powdery patches on bread mold colonies |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporangiophore Development: Hyphal cells differentiate into sporangiophores, specialized structures that support spore formation

- Sporangium Formation: Sporangiophores produce sporangia, sac-like structures where spores develop and mature

- Meiosis in Spores: Spores form via meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability in mold populations

- Environmental Triggers: Factors like nutrient depletion, light, and humidity signal spore production in bread mold

- Spore Release Mechanism: Mature spores are released through sporangium rupture, dispersing via air currents

Sporangiophore Development: Hyphal cells differentiate into sporangiophores, specialized structures that support spore formation

Sporangiophores are the unsung heroes of bread mold's reproductive strategy, emerging as specialized structures from hyphal cells to support spore formation. This differentiation process is triggered by environmental cues such as nutrient depletion, light exposure, or changes in humidity. Once initiated, hyphal cells elongate and branch, forming aerial structures that elevate spore-bearing sporangia above the mold colony. This elevation is critical for spore dispersal, ensuring that the mold's offspring can travel to new food sources.

Consider the transformation of hyphal cells into sporangiophores as a strategic shift from vegetative growth to reproductive mode. Hyphal cells, typically focused on nutrient absorption and colony expansion, reallocate resources to construct these specialized structures. The process involves cellular reprogramming, where genes responsible for sporangiophore development are upregulated, and those for vegetative growth are downregulated. This genetic shift is finely tuned, ensuring that sporangiophores develop only when conditions favor successful spore dispersal.

To observe sporangiophore development, place a slice of bread in a humid environment and monitor it over 5–7 days. Initially, you’ll see white, thread-like hyphae spreading across the surface. As nutrients deplete, aerial hyphae will rise, and within 48–72 hours, sporangiophores will emerge, topped with spherical sporangia containing spores. For optimal observation, use a magnifying glass or low-power microscope to track the transition from hyphal growth to sporangiophore formation. Avoid excessive moisture, as it can lead to bacterial contamination, and ensure adequate airflow to prevent waterlogging.

The efficiency of sporangiophore development is a testament to bread mold's adaptability. For instance, *Rhizopus stolonifer*, a common bread mold, can produce sporangiophores within 24 hours under ideal conditions (25°C and 80% humidity). This rapid response allows the mold to capitalize on transient food sources before competitors arrive. Practical tip: To inhibit sporangiophore formation and slow mold growth, store bread in a cool, dry place (below 15°C and 60% humidity), as these conditions suppress the environmental triggers for differentiation.

Comparing sporangiophore development across mold species reveals fascinating variations. While *Rhizopus* produces tall, erect sporangiophores, *Penicillium* forms brush-like structures with smaller sporangia. These differences reflect adaptations to specific dispersal mechanisms—wind for *Penicillium* and gravity or insects for *Rhizopus*. Understanding these distinctions can inform strategies for mold control, such as using airflow to disrupt spore release in *Penicillium*-prone environments or employing physical barriers to contain *Rhizopus* colonies.

Spore's Toolboxes in Call of Chernobyl: Fact or Fiction?

You may want to see also

Sporangium Formation: Sporangiophores produce sporangia, sac-like structures where spores develop and mature

Spores in bread mold, a common sight in forgotten sandwiches, are the result of a fascinating reproductive process centered around the sporangium. This sac-like structure, produced by specialized hyphae called sporangiophores, serves as the cradle for spore development. Understanding this process not only sheds light on fungal biology but also offers insights into preventing mold growth in food.

Sporangiophores, akin to miniature scaffolding, extend upward from the mold’s mycelium, the network of thread-like filaments. At their tips, sporangia form, swelling with cytoplasm and nuclei. Within these sacs, spores develop through a process called sporogenesis, where cellular division and differentiation occur. This stage is critical, as spores are the mold’s survival units, capable of withstanding harsh conditions like dryness and extreme temperatures.

The formation of sporangia is a highly regulated process, influenced by environmental factors such as humidity, temperature, and nutrient availability. Optimal conditions—typically warm, damp environments—accelerate sporangium development. For instance, bread left in a humid kitchen can develop visible mold colonies within 24 to 48 hours, with sporangia appearing as powdery or fuzzy patches. These structures are not merely passive containers; they actively contribute to spore maturation by providing nutrients and structural support.

To disrupt this process and prevent mold growth, practical measures can be taken. Storing bread in a cool, dry place reduces humidity, slowing sporangiophore development. Refrigeration, which lowers temperatures to around 4°C (39°F), significantly inhibits mold growth by slowing metabolic processes. Additionally, airtight containers limit oxygen availability, another factor essential for sporangium formation. For those dealing with recurring mold issues, using desiccants like silica gel packets in bread storage areas can absorb excess moisture, creating an unfavorable environment for mold.

Comparatively, the sporangium formation in bread mold shares similarities with other fungal reproductive strategies, such as the production of asci in yeasts or conidia in certain fungi. However, the sporangium’s sac-like structure and its external development on sporangiophores make it uniquely adapted for spore dispersal. When mature, sporangia release spores through rupture or passive dispersion, often aided by air currents. This efficiency in dispersal explains why mold can quickly colonize new areas, from kitchen counters to entire loaves of bread.

In conclusion, sporangium formation is a pivotal step in the life cycle of bread mold, driven by the specialized function of sporangiophores. By understanding this process, we can implement targeted strategies to prevent mold growth, from controlling environmental conditions to using storage solutions. Whether you’re a homeowner battling kitchen mold or a food scientist studying fungal biology, recognizing the role of sporangia offers both practical and theoretical value.

Are All Amanita Spore Prints White? Unveiling Mushroom Identification Myths

You may want to see also

Meiosis in Spores: Spores form via meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability in mold populations

Spores in bread mold, those tiny agents of decay, owe their existence to meiosis, a specialized form of cell division. Unlike mitosis, which produces genetically identical cells, meiosis shuffles genetic material, creating spores with unique combinations of traits. This process is crucial for mold survival, as it generates diversity within populations, equipping them to adapt to changing environments, resist threats, and exploit new resources.

Think of it as nature's way of ensuring mold's longevity through constant innovation at the microscopic level.

The meiotic process in spore formation involves two rounds of cell division, reducing the chromosome number by half. This reduction is essential for sexual reproduction in molds. When spores germinate and encounter compatible mates, their haploid nuclei fuse, restoring the full chromosome set. This sexual cycle, fueled by meiosis, acts as a genetic reset button, purging harmful mutations and introducing beneficial variations. Without meiosis, mold populations would stagnate, vulnerable to diseases and environmental shifts.

For instance, a mold strain resistant to a particular fungicide could emerge through meiotic recombination, ensuring the species' survival despite human intervention.

This genetic diversity conferred by meiosis translates into tangible advantages for mold populations. It allows them to colonize diverse substrates, from bread to decaying leaves, and withstand fluctuations in temperature, humidity, and nutrient availability. Imagine a mold spore landing on a slice of bread left in a humid kitchen. Its genetic makeup, shaped by meiosis, might contain traits enabling it to thrive in this specific environment, outcompeting other microorganisms and claiming the bread as its own. This adaptability is a direct consequence of the genetic shuffling that occurs during spore formation.

Consequently, understanding meiosis in spores is not just an academic exercise; it's key to developing effective mold control strategies, from food preservation to building maintenance.

While meiosis is fundamental to spore formation, it's not without its vulnerabilities. Environmental stressors like extreme temperatures or radiation can disrupt the process, leading to malformed or non-viable spores. This knowledge can be harnessed to develop targeted mold control methods. For example, exposing mold to controlled heat treatments during its meiotic phase could potentially disrupt spore production, offering a more precise and environmentally friendly alternative to broad-spectrum fungicides. By understanding the intricacies of meiosis in spores, we gain valuable insights into both the resilience and the weaknesses of these ubiquitous organisms.

Basidiomycete Pathogens Without Spores: Monocyclic or Not?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Triggers: Factors like nutrient depletion, light, and humidity signal spore production in bread mold

Bread mold, a common sight on forgotten slices and stale loaves, doesn't sporulate on a whim. Its transition from fuzzy invader to spore-producing factory is a calculated response to its environment. Think of it as a survival strategy triggered by specific cues. When nutrients, the mold's primary fuel source, become scarce, it senses the impending famine. This depletion acts as a red flag, prompting the mold to shift gears and invest its remaining energy into producing spores, tiny, resilient survival pods capable of enduring harsh conditions until they find a new, nutrient-rich home.

Studies show that nutrient depletion, particularly a lack of nitrogen, is a potent trigger for spore formation in *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* species, common bread mold culprits.

Light, often overlooked, plays a surprising role in this process. While some molds thrive in darkness, others, like *Neurospora crassa*, use light as a signal to initiate sporulation. This photoresponse is mediated by specialized proteins that detect specific wavelengths, primarily in the blue light spectrum. Imagine a mold colony sensing the faint glow from your kitchen window, interpreting it as a sign of potential competition or environmental change, and responding by producing spores to ensure its genetic continuity.

Understanding this light sensitivity can be practically applied. Storing bread in complete darkness, using opaque containers, can potentially delay spore formation, buying you precious time before the mold takes over.

Humidity, the invisible moisture in the air, is another critical factor. Bread mold thrives in damp environments, and high humidity levels provide the ideal conditions for spore germination and growth. However, when humidity drops, the mold perceives a threat to its water supply. This stressor, similar to nutrient depletion, triggers a survival response, prompting the mold to produce spores capable of withstanding drier conditions. Maintaining a relatively dry environment, around 40-50% humidity, can discourage spore formation and slow down mold growth. Consider using a dehumidifier in your kitchen or storing bread in a cool, dry place.

These environmental triggers – nutrient depletion, light, and humidity – act as a complex language, communicating to the mold the state of its surroundings. By understanding this language, we can manipulate these factors to our advantage. While completely preventing mold growth on bread is nearly impossible, controlling these triggers can significantly delay its onset and extend the shelf life of our baked goods. Remember, the battle against bread mold is not just about cleanliness; it's about understanding the enemy's language and using its own signals against it.

Uninstalling Spore: What Happens to Your Creations? Find Out Now

You may want to see also

Spore Release Mechanism: Mature spores are released through sporangium rupture, dispersing via air currents

Bread mold, a common sight on forgotten slices, is a fascinating organism with a sophisticated reproductive strategy. At the heart of its lifecycle is the sporangium, a sac-like structure that houses mature spores. These spores are the mold's offspring, waiting for the perfect moment to embark on their journey to new habitats. The release mechanism is a dramatic event, akin to a microscopic explosion, where the sporangium ruptures, propelling spores into the air. This process is not random but a finely tuned response to environmental cues, ensuring the mold's survival and propagation.

Imagine a tiny, pressurized container bursting open, releasing its contents into the wind. This is the essence of spore release in bread mold. The sporangium, typically located at the tip of a stalk-like structure called a sporangiophore, accumulates turgor pressure as the spores mature. When conditions are optimal—often signaled by factors like humidity, temperature, and nutrient availability—the sporangium wall weakens, leading to rupture. This sudden release creates a cloud of spores that can travel significant distances on air currents, sometimes even reaching other rooms in a house. For instance, a single mold colony on a stale loaf can disperse thousands of spores in a matter of minutes, each capable of starting a new colony under favorable conditions.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this mechanism can help in controlling mold growth. To minimize spore dispersal, it’s crucial to address mold at the first sign of growth. Sealing contaminated bread in a plastic bag before disposal prevents spores from becoming airborne. Additionally, maintaining low humidity levels (below 60%) and promptly refrigerating bread can inhibit mold development. For those with allergies or respiratory sensitivities, using HEPA filters can capture airborne spores, reducing indoor exposure.

Comparatively, the spore release mechanism of bread mold shares similarities with other fungi, such as mushrooms, which also rely on air currents for spore dispersal. However, bread mold’s rapid lifecycle and ability to thrive in indoor environments make its spore release particularly efficient and problematic. Unlike outdoor fungi, which often rely on wind or water for dispersal, bread mold has adapted to exploit the confined spaces of human dwellings, where air movement is limited but still sufficient for spore travel.

In conclusion, the spore release mechanism of bread mold is a remarkable example of nature’s ingenuity. By rupturing the sporangium, the mold ensures its spores are dispersed widely and efficiently, maximizing the chances of colonization. This process, while essential for the mold’s survival, poses challenges for humans, particularly in food storage and indoor air quality. By understanding and mitigating this mechanism, we can better manage mold growth and its associated risks.

How Spores Transform Milk into Cheese: The Science Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores in bread mold (typically *Rhizopus stolonifer*) form under conditions of high humidity, warmth (20–30°C or 68–86°F), and limited nutrients. As the mold matures, it produces sporangia, which release spores into the air for dispersal.

Bread mold spores develop within structures called sporangia, which form at the tips of the mold’s hyphae. When mature, the sporangia release spores, which are lightweight and easily dispersed through the air, allowing the mold to colonize new food sources.

Spores can form on both fresh and moldy bread, but they are more likely to develop on moldy bread as the mold colony matures. Fresh bread provides nutrients for initial mold growth, while moldy bread supports the later stages of spore production and release.