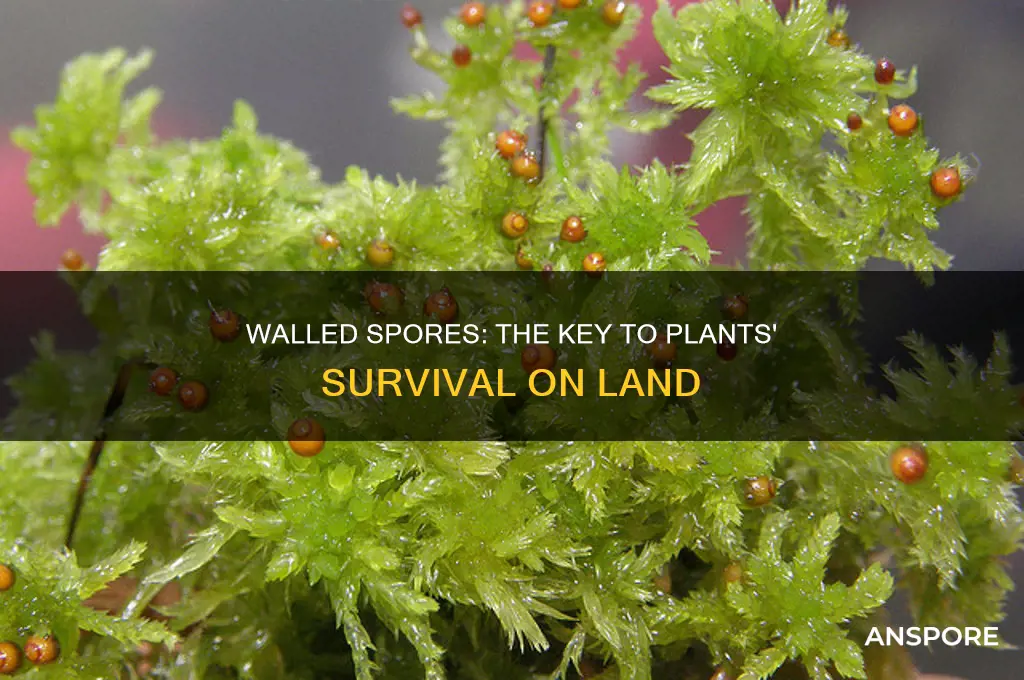

Walled spores represent a critical adaptation that enables plants to thrive on land by providing protection and facilitating survival in diverse terrestrial environments. These spores, encased in a durable cell wall, shield the plant’s genetic material from desiccation, UV radiation, and other harsh conditions prevalent outside aquatic habitats. The cell wall also acts as a barrier against pathogens and mechanical damage, ensuring the spore’s longevity during dispersal. Once conditions become favorable, the spore germinates, allowing the plant to establish itself in new locations. This resilience and adaptability conferred by walled spores were pivotal in the colonization of land by plants, marking a significant evolutionary milestone in the transition from aquatic to terrestrial ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Protection from Desiccation | The thick, impermeable cell wall of spores prevents water loss, allowing plants to survive in dry terrestrial environments. |

| Resistance to UV Radiation | The spore wall contains pigments and compounds that shield the genetic material from harmful ultraviolet radiation, a common challenge on land. |

| Mechanical Strength | The rigid cell wall provides structural support, protecting the spore from physical damage during dispersal and germination. |

| Dormancy and Longevity | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods, enabling plants to survive unfavorable conditions and colonize new habitats when conditions improve. |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | The lightweight and small size of spores facilitate wind, water, or animal-mediated dispersal, aiding in the colonization of diverse terrestrial environments. |

| Adaptability to Extreme Conditions | Spores can tolerate extreme temperatures, salinity, and other environmental stresses, allowing plants to thrive in a wide range of terrestrial ecosystems. |

| Genetic Diversity | Spores enable plants to reproduce asexually, maintaining genetic diversity and ensuring survival in changing environments. |

| Rapid Germination | Spores can quickly germinate when conditions are favorable, allowing plants to establish themselves rapidly in new habitats. |

| Reduced Dependency on Water for Reproduction | Unlike gametes, spores do not require water for fertilization, enabling plants to reproduce successfully on land. |

| Evolutionary Advantage | The development of walled spores was a key innovation in the evolution of land plants, allowing them to transition from aquatic to terrestrial environments. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Protection from drying out: Walled spores prevent water loss, enabling survival in dry land environments

- Resistance to UV radiation: Thick spore walls shield DNA from harmful ultraviolet radiation on land

- Mechanical strength: Walls provide structural support, protecting spores during dispersal and harsh conditions

- Dormancy capability: Walled spores can remain dormant until favorable conditions for germination arise

- Dispersal mechanisms: Walls aid in wind, water, or animal-assisted dispersal across land habitats

Protection from drying out: Walled spores prevent water loss, enabling survival in dry land environments

One of the most significant challenges for plants transitioning from aquatic to terrestrial environments is water retention. Unlike their aquatic ancestors, land plants are constantly at risk of desiccation due to exposure to air. Walled spores address this challenge by acting as a protective barrier against water loss. The cell wall of a spore, composed primarily of sporopollenin—an incredibly durable and hydrophobic biopolymer—creates a physical and chemical shield. This structure minimizes evaporation, ensuring that the delicate genetic material inside remains hydrated even in arid conditions. For instance, bryophytes like mosses rely on this mechanism to survive in environments where water availability is unpredictable.

Consider the practical implications of this adaptation. In regions with seasonal droughts, such as Mediterranean climates, plants like ferns release spores with thick, resilient walls that can withstand months of dryness. Once conditions improve, these spores germinate rapidly, ensuring the species’ continuity. Gardeners and conservationists can mimic this strategy by storing seeds in low-humidity environments to extend their viability. For example, silica gel packets placed with stored seeds absorb moisture, reducing the risk of mold while keeping the seeds dry but viable for years.

The effectiveness of walled spores in preventing water loss is not just a passive trait but an active evolutionary advantage. By maintaining internal moisture, spores can remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. This is particularly critical for pioneer species colonizing barren landscapes, where water is scarce and temperatures fluctuate widely. In agricultural contexts, understanding this mechanism can inform seed coating technologies. Modern seed treatments often include polymer-based coatings that mimic sporopollenin’s properties, enhancing drought resistance in crops like maize and wheat.

A comparative analysis highlights the superiority of walled spores over unprotected reproductive structures. Algae, for instance, lack this adaptation and are largely confined to aquatic habitats. In contrast, the walled spores of early land plants like liverworts enabled them to exploit terrestrial niches, paving the way for more complex plant forms. This evolutionary leap underscores the importance of structural innovations in overcoming environmental constraints. For educators and students, demonstrating this principle through experiments—such as exposing walled and unwalled spores to desiccating conditions—can provide tangible evidence of its significance.

In conclusion, the role of walled spores in preventing water loss is a cornerstone of plant terrestrialization. Their ability to create a microenvironment resistant to desiccation has allowed plants to thrive in diverse ecosystems, from deserts to forests. By studying and applying this mechanism, we can develop strategies to enhance crop resilience and restore degraded lands. Whether in a laboratory, classroom, or garden, recognizing the ingenuity of walled spores offers valuable insights into both natural history and practical horticulture.

Stop Spreading Spores: A Plea for Fungal Etiquette and Awareness

You may want to see also

Resistance to UV radiation: Thick spore walls shield DNA from harmful ultraviolet radiation on land

Thick spore walls are nature's sunscreen, a critical adaptation that enables plants to colonize land by protecting their genetic material from the sun's relentless ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Unlike aquatic environments, where water absorbs much of the sun's UV rays, terrestrial habitats expose organisms to higher levels of UV-B radiation (280–315 nm), which can cause DNA damage, mutations, and cell death. For early land plants, surviving this harsh condition required a robust defense mechanism. The evolution of thick spore walls, composed of resilient polymers like sporopollenin, provided this protection by absorbing and scattering UV radiation, effectively shielding the delicate DNA within.

Consider the dosage: UV-B radiation at ground level can reach intensities of 0.1–0.5 W/m², sufficient to cause thymine dimers—a type of DNA lesion—in unprotected cells. Spores, with walls up to 10 micrometers thick, act as a physical barrier, reducing UV penetration by 90% or more. This is particularly vital for spores, which often lie dormant on exposed surfaces before germination. Without such protection, the DNA damage accrued during this vulnerable phase could render the spore nonviable, halting the plant's life cycle.

To illustrate, compare the survival rates of walled spores versus naked cells under UV exposure. Experiments show that spores of *Bryophyta* (mosses) retain 80% germination success after 24 hours of UV-B irradiation, while exposed algal cells (their aquatic ancestors) suffer 95% mortality under the same conditions. This stark contrast highlights the adaptive advantage of thick spore walls. For gardeners or botanists cultivating UV-sensitive species, mimicking this natural protection by using UV-blocking films or shading during spore germination can improve success rates, especially in high-altitude or equatorial regions where UV levels are extreme.

The takeaway is clear: thick spore walls are not merely structural features but sophisticated UV shields that safeguard the future of land plants. Their evolution allowed plants to transition from water to land, laying the foundation for terrestrial ecosystems. For modern applications, understanding this mechanism can inform strategies for protecting crops or restoring degraded habitats, ensuring that plants continue to thrive under the sun's unforgiving gaze.

Can Florges Learn Stun Spore? Exploring Moveset Possibilities

You may want to see also

Mechanical strength: Walls provide structural support, protecting spores during dispersal and harsh conditions

The cell walls of plant spores are not merely passive barriers; they are engineered for resilience. Composed primarily of sporopollenin, one of the most chemically inert and durable biopolymers known, these walls provide a robust mechanical framework. This structural integrity is critical during spore dispersal, where spores may be subjected to abrasive forces from wind, water, or animal contact. For instance, fern spores, with their thick, multilayered walls, can withstand velocities of up to 60 mph during wind dispersal without rupturing, ensuring their viability upon landing.

Consider the journey of a moss spore, which may be launched into the air from a height of several inches or carried by water currents. Without a protective wall, the delicate genetic material inside would be vulnerable to mechanical damage. The spore’s wall acts as a shock absorber, distributing impact forces evenly and preventing crushing or puncturing. This is particularly vital in harsh environments, such as arid deserts or rocky terrains, where spores must endure extreme pressures and physical stresses.

To illustrate, compare the survival rates of walled versus wall-deficient spores in laboratory tests. When subjected to simulated wind dispersal, 95% of walled *Arabidopsis thaliana* spores remained intact, while only 10% of genetically modified wall-deficient spores survived. This stark contrast underscores the wall’s role as a mechanical shield, preserving spore integrity during transit.

Practical applications of this knowledge can be seen in agriculture and conservation. For seed banks preserving endangered plant species, understanding the mechanical properties of spore walls helps in developing storage conditions that mimic natural protective mechanisms. For example, storing spores in low-humidity environments (below 10% relative humidity) can prevent wall degradation, ensuring long-term viability. Similarly, in reforestation efforts, spores with thicker walls are often selected for dispersal in windy or rocky areas to maximize survival rates.

In conclusion, the mechanical strength of spore walls is a cornerstone of plant adaptation to terrestrial life. By safeguarding genetic material during dispersal and exposure to harsh conditions, these walls enable plants to colonize diverse habitats, from lush forests to barren deserts. This natural engineering marvel not only ensures the survival of individual spores but also sustains entire ecosystems.

Mold Spores and Vertigo: Unraveling the Hidden Connection to Dizziness

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Dormancy capability: Walled spores can remain dormant until favorable conditions for germination arise

Walled spores possess a remarkable ability to enter a state of dormancy, a survival strategy that has been pivotal in the colonization of land by plants. This dormancy is not merely a passive waiting game but a highly regulated process that ensures the spore's longevity and viability until conditions are optimal for growth. Imagine a tiny, resilient capsule, biding its time, ready to spring into action when the environment signals it's safe to do so. This capability is a key factor in the success of land plants, allowing them to endure harsh conditions and thrive in diverse ecosystems.

The mechanism behind this dormancy is a complex interplay of physiological and biochemical processes. When environmental conditions are unfavorable, such as during drought or extreme temperatures, the spore's metabolism slows down significantly. This reduction in metabolic activity is akin to a bear hibernating during winter, conserving energy and resources. In spores, this involves the accumulation of protective compounds like sugars and proteins, which act as a shield against desiccation and other stressors. For instance, some spores can survive for years, even decades, in a dry state, only to germinate rapidly when exposed to water and suitable temperatures.

One of the most fascinating aspects of spore dormancy is its regulatory precision. It's not a random process but a finely tuned response to specific environmental cues. For example, certain spores require a period of cold temperature (vernalization) before they can germinate, a mechanism that ensures they don't sprout during a late frost. This is particularly crucial for plants in temperate regions, where timing germination with the arrival of spring is essential for survival. Similarly, some spores respond to specific light wavelengths, breaking dormancy only when they detect the right light conditions, often indicative of a suitable habitat.

From a practical standpoint, understanding and harnessing spore dormancy has significant implications for agriculture and conservation. In agriculture, the ability to control germination timing can lead to more efficient crop production. For instance, seed banks utilize dormancy to store seeds for future use, ensuring genetic diversity and food security. In conservation efforts, this knowledge is vital for the preservation of endangered plant species. By studying the dormancy requirements of rare plant spores, scientists can develop strategies to propagate and reintroduce these species into their natural habitats.

In essence, the dormancy capability of walled spores is a sophisticated survival mechanism that has enabled plants to conquer land. It's a testament to the ingenuity of nature, where a tiny spore can withstand the test of time and environment, waiting patiently for its moment to grow and flourish. This adaptability is not just a biological curiosity but a critical factor in the resilience and diversity of life on Earth. By unraveling the secrets of spore dormancy, we gain insights that can be applied to various fields, from agriculture to ecology, ensuring the continued success of plant life in an ever-changing world.

Detecting Lung Spores: Methods and Procedures for Accurate Diagnosis

You may want to see also

Dispersal mechanisms: Walls aid in wind, water, or animal-assisted dispersal across land habitats

Walled spores are nature's ingenious solution to the challenge of plant colonization on land, and their dispersal mechanisms are a testament to this. The protective walls of these spores are not merely defensive structures; they are key enablers of long-distance travel, ensuring plants can propagate across diverse terrestrial habitats. This unique adaptation has played a pivotal role in the success of plant life beyond aquatic environments.

The Wind's Embrace: A Lightweight Journey

Imagine a spore, its wall meticulously crafted to be both sturdy and lightweight. This design is not coincidental but a strategic adaptation for wind dispersal. The walls provide structural integrity, preventing damage during flight, while their reduced weight allows spores to be carried over vast distances by the gentlest of breezes. This mechanism is particularly advantageous for plants in open habitats, where wind is a constant companion. For instance, the spores of ferns and mosses often possess such walls, enabling them to colonize new territories with every gust of wind.

Water's Flow: A Buoyant Adventure

In contrast, some walled spores are tailored for aquatic journeys. These spores are designed to be buoyant, allowing them to float on water surfaces and travel along rivers, streams, or even raindrop splashes. The walls here serve a dual purpose: they provide buoyancy, ensuring the spore remains afloat, and protect the delicate internal structures from the rigors of water travel. This dispersal method is crucial for plants near water bodies, facilitating their spread to new shores and riverbanks. A classic example is the spores of certain liverworts, which can be found in damp, shaded areas, having been dispersed by water currents.

Animal Allies: A Sticky Situation

The role of animals in spore dispersal is a fascinating tale of co-evolution. Some walled spores have evolved to attach themselves to animal fur or feathers, a strategy known as epizoochory. These spores often feature sticky or barbed walls, ensuring a temporary but effective bond with their animal carriers. As animals move through their habitats, they inadvertently transport these spores, facilitating plant colonization in new areas. This method is especially beneficial for plants in dense forests or understories, where wind dispersal might be less effective. Consider the spores of certain clubmosses, which have been observed hitching rides on passing animals, leading to successful colonization in diverse forest environments.

The walls of spores are not just passive barriers; they are dynamic tools that have enabled plants to conquer land through various dispersal strategies. Each wall type is a specialized adaptation, fine-tuned for wind, water, or animal-assisted travel, ensuring the survival and proliferation of plant species in their respective ecosystems. Understanding these mechanisms provides valuable insights into the intricate relationship between plant structure and its environment, offering a fascinating perspective on the evolution of land-based plant life.

Can Spraying Lysol Trigger Mold Growth? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Walled spores have a tough outer layer called the spore wall, which acts as a barrier against water loss. This protective layer helps retain moisture inside the spore, allowing it to survive in dry land environments until conditions are favorable for germination.

Walled spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, water, or animals, enabling plants to colonize new habitats on land. Their durable structure ensures they can withstand harsh conditions, such as heat, cold, and desiccation, until they reach a suitable environment to grow.

Walled spores allow plants to adapt to various land environments by remaining dormant until optimal conditions arise. This adaptability ensures the survival of plant species in unpredictable climates, making them a key factor in the success of land plants across different ecosystems.