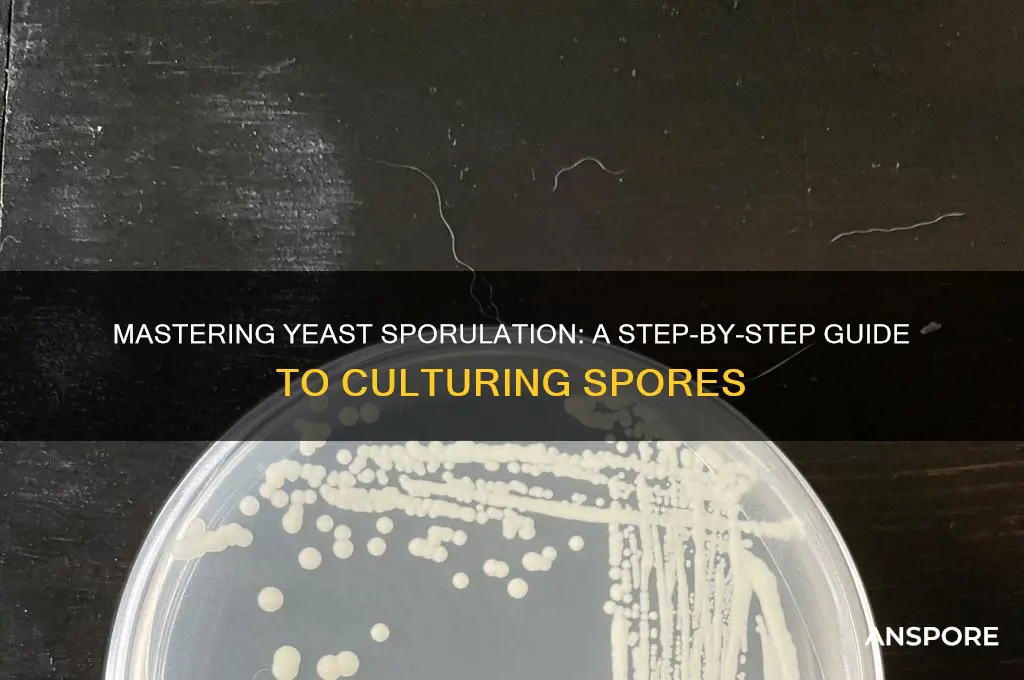

Preparing yeast cultures to create spores involves a precise and controlled process that begins with selecting a suitable yeast strain, typically *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*. The yeast is first cultured in a nutrient-rich medium, such as YPD (yeast extract, peptone, dextrose), to promote vegetative growth. Once the culture reaches its exponential phase, it is transferred to a sporulation medium, often minimal in nutrients, such as potassium acetate or nitrogen-depleted medium, to induce sporulation. The culture is then incubated under optimal conditions, typically at a lower temperature (around 25°C), with gentle agitation to ensure oxygenation. Over several days, the yeast cells undergo meiosis and form tetrads of spores, which can be confirmed microscopically. The spores are then harvested, purified, and stored for further use in genetic studies, fermentation processes, or other applications. Careful monitoring of environmental factors, such as pH and temperature, is crucial to ensure successful sporulation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Yeast Species | Typically, ascospores are produced by ascomycete yeasts (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe). Sporulation efficiency varies by strain. |

| Growth Medium | Sporulation-inducing media (e.g., sporulation agar or liquid medium) with limited nitrogen (e.g., 0.5% potassium acetate) and enriched with nutrients like vitamins and minerals. |

| Carbon Source | Non-fermentable carbon sources like acetate or glycerol are preferred to promote sporulation. |

| Nitrogen Limitation | Critical for sporulation; nitrogen depletion triggers the sporulation pathway. |

| Temperature | Optimal temperature ranges from 25°C to 30°C, depending on the species. |

| pH Level | Slightly acidic to neutral pH (5.0–7.0) is ideal for most yeast species. |

| Oxygen Availability | Aerobic conditions are necessary for efficient sporulation. |

| Time Duration | Sporulation typically takes 3–7 days, depending on the strain and conditions. |

| Cell Density | Cultures should reach stationary phase (high cell density) before inducing sporulation. |

| Sporulation Efficiency | Varies by strain; diploid or heterozygous strains generally sporulate more efficiently. |

| Microscopic Verification | Spores are verified using microscopy; mature spores appear as refractile, oval structures within asci. |

| Storage | Spores can be stored long-term at -80°C or in glycerol stocks for future use. |

| Genetic Factors | Sporulation requires functional genes in the sporulation pathway (e.g., SPO11, SPO13). |

| Contamination Control | Sterile conditions are essential to prevent bacterial or fungal contamination. |

| Post-Sporulation Treatment | Spores may be isolated by digestion of asci using enzymes like Zymolyase or mechanical disruption. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sterilize Equipment: Autoclave all glassware, tools, and media to prevent contamination during spore preparation

- Select Yeast Strain: Choose a sporulating yeast strain (e.g., *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*) for optimal results

- Prepare Sporulation Media: Use nutrient-limited media (e.g., potassium acetate) to induce spore formation

- Inoculate and Incubate: Transfer yeast cells to sporulation media and incubate under controlled conditions

- Harvest and Verify Spores: Collect spores via centrifugation and confirm sporulation using microscopy or staining

Sterilize Equipment: Autoclave all glassware, tools, and media to prevent contamination during spore preparation

Contamination is the arch-nemesis of any spore preparation process, capable of derailing weeks of work in a matter of hours. To safeguard your yeast cultures, sterilization of all equipment is non-negotiable. Autoclaving, a process that uses steam under pressure to kill microorganisms, is the gold standard for this task. It ensures that glassware, tools, and media are free from bacteria, fungi, and other contaminants that could compromise your experiment.

The autoclave operates at temperatures between 121°C and 134°C, with a pressure of 15-20 psi, for a minimum of 15-30 minutes, depending on the load size and type of materials. Glassware, such as Petri dishes, flasks, and pipettes, should be cleaned thoroughly before autoclaving to remove any debris that might interfere with sterilization. Tools like scalpels, forceps, and spreaders must be made of materials that can withstand high temperatures and pressure, typically stainless steel or heat-resistant plastics.

Media, including agar and liquid broths, require special attention. Prepare the media according to your protocol, then dispense it into sterile containers before autoclaving. Ensure that the containers are not filled to the brim, as the media will expand during the process. For solid media like agar, autoclave for 20-30 minutes, while liquid media may require slightly less time, around 15-20 minutes. Always allow the autoclave to cool down naturally to avoid contamination from external sources.

A common mistake is to assume that autoclaving is a one-size-fits-all solution. Different materials have varying heat and pressure tolerances. For instance, plastic items should be placed on the upper shelves of the autoclave to prevent melting, while glassware can be positioned lower. Additionally, use autoclave tape on the lids of containers to indicate whether the sterilization process was successful. If the tape changes color (usually from white to black), it confirms that the appropriate temperature was reached.

Incorporating a sterilization checklist can further enhance your workflow. Before starting, verify that all items are autoclave-safe, properly cleaned, and correctly loaded. After autoclaving, inspect the equipment for any signs of damage or residual contamination. Store sterilized items in a designated, clean area until use. By meticulously sterilizing your equipment, you create a contamination-free environment that is essential for successful yeast spore preparation.

Can Rubbing Alcohol Effectively Kill Bacterial Spores? The Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Select Yeast Strain: Choose a sporulating yeast strain (e.g., *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*) for optimal results

Selecting the right yeast strain is the cornerstone of successful spore production. Not all yeasts sporulate, and even among those that do, efficiency varies widely. *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, a well-studied and readily available strain, is a popular choice for its robust sporulation capabilities under controlled conditions. This yeast, commonly known as baker’s or brewer’s yeast, transitions from vegetative growth to spore formation when subjected to nutrient deprivation, particularly nitrogen limitation. Its genetic tractability and extensive research background make it an ideal candidate for both laboratory experiments and industrial applications.

To initiate sporulation, start by culturing *S. cerevisiae* in a rich medium like YPD (yeast extract, peptone, dextrose) to promote vegetative growth. Once the culture reaches stationary phase (typically 12–16 hours), transfer the cells to a sporulation medium such as potassium acetate (2% w/v) or SPS (sporulation medium). These media are nitrogen-poor, triggering the cells to enter the sporulation pathway. Maintain the culture at 25–30°C with gentle agitation to ensure oxygen availability, which is critical for spore development. Sporulation efficiency can be enhanced by optimizing pH (around 6.0) and avoiding contaminants that might compete for resources.

While *S. cerevisiae* is a reliable choice, it’s not the only option. Other sporulating yeasts, such as *Schizosaccharomyces pombe* or *Kluyveromyces lactis*, may be preferred for specific applications. However, *S. cerevisiae* stands out for its high sporulation rates (up to 90% under optimal conditions) and resilience. For instance, strains like SK1 and Sigma 1278b are widely used in genetic studies due to their consistent sporulation performance. When selecting a strain, consider factors like sporulation time (typically 3–5 days for *S. cerevisiae*), spore viability, and compatibility with downstream processes.

A critical caution: not all *S. cerevisiae* strains sporulate equally. Commercial strains optimized for baking or brewing may lack the genetic capacity for efficient sporulation. Always verify the strain’s sporulation history or use well-characterized laboratory strains. Additionally, avoid over-aeration or agitation, as this can disrupt cell aggregation, a key step in spore formation. Regularly monitor the culture under a microscope to confirm the presence of asci (spore-containing sacs), ensuring the process is on track.

In conclusion, choosing *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* as your sporulating yeast strain sets a strong foundation for spore production. Its reliability, coupled with a wealth of research and resources, simplifies the process for both novices and experts. By adhering to specific culturing conditions and selecting proven strains, you can maximize sporulation efficiency and yield, paving the way for successful experiments or applications.

Do All Land Plant Groups Produce Spores? Exploring Plant Reproduction

You may want to see also

Prepare Sporulation Media: Use nutrient-limited media (e.g., potassium acetate) to induce spore formation

Yeast sporulation is a survival mechanism triggered by nutrient deprivation, particularly the lack of nitrogen. To induce spore formation, researchers and brewers alike turn to nutrient-limited media, with potassium acetate being a prime example. This approach mimics the natural conditions that prompt yeast to enter a dormant, spore-like state. By carefully controlling the nutrient composition of the growth medium, you can coax yeast cells into producing spores, a process that has applications in both scientific research and industrial fermentation.

The key to successful sporulation lies in the precise formulation of the nutrient-limited media. Potassium acetate, a carbon source that lacks nitrogen, is commonly used to create an environment that encourages spore formation. Typically, a sporulation medium contains 1% potassium acetate, 0.1% yeast extract, and various salts, such as potassium phosphate and ammonium sulfate, to maintain optimal pH and ion balance. It's essential to sterilize the medium before use, either by autoclaving or filtration, to prevent contamination that could hinder sporulation.

When preparing the sporulation medium, consider the following steps: First, dissolve the potassium acetate and yeast extract in distilled water, ensuring complete solubility. Next, add the salt components, adjusting the pH to 6.5-7.0 using a sterile solution of potassium hydroxide or acetic acid. Finally, distribute the medium into sterile containers, such as test tubes or flasks, and inoculate with a late-logarithmic phase yeast culture at a concentration of 1-2 x 10^7 cells/mL. Incubate the cultures at 25-30°C with shaking to promote aeration, which is crucial for efficient sporulation.

One of the critical factors in sporulation media preparation is the timing of nutrient limitation. Yeast cells must be in a specific physiological state to respond to the nutrient-limited environment. Generally, cells are grown to late-logarithmic phase in a rich medium, such as YPD (yeast extract, peptone, dextrose), before being transferred to the sporulation medium. This two-step process ensures that the cells have sufficient resources to commit to sporulation. Be cautious not to overexpose the cells to the nutrient-limited conditions, as prolonged starvation can lead to cell death rather than sporulation.

In practice, the use of potassium acetate-based sporulation media has been widely adopted in laboratories studying yeast biology. For instance, researchers investigating the molecular mechanisms of sporulation often rely on this method to produce large quantities of spores for analysis. Similarly, in the brewing industry, sporulation media can be used to create spore banks of specific yeast strains, ensuring a consistent supply of viable cells for fermentation. By mastering the art of sporulation media preparation, you can unlock new possibilities in yeast research and applications, from fundamental biology to industrial-scale production.

Dormant Mold Spores: Hidden Health Risks and Safety Concerns

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Inoculate and Incubate: Transfer yeast cells to sporulation media and incubate under controlled conditions

Yeast sporulation is a delicate process that requires precise control of environmental conditions to trigger the transition from vegetative growth to spore formation. The inoculation and incubation phase is critical, as it sets the stage for successful spore development. To begin, transfer a small volume of yeast culture—typically 1–2% inoculum—into a sporulation medium, such as potassium acetate (2% w/v) or nitrogen-depleted media, which are known to induce sporulation in species like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*. This step ensures a low starting cell density, allowing ample nutrients for spore development without overcrowding.

The incubation conditions must be tightly regulated to mimic the natural stress signals that yeast encounter in their environment. Maintain the culture at 25–30°C, as higher temperatures can inhibit sporulation, while lower temperatures may slow the process excessively. Agitation, such as shaking at 200–250 rpm, is essential to ensure uniform nutrient distribution and oxygen availability, both of which are critical for efficient spore formation. Monitor the culture periodically using phase-contrast microscopy to observe the progression of sporulation, which typically peaks between 24 and 72 hours depending on the strain and conditions.

A key consideration during incubation is the gradual depletion of nutrients, particularly nitrogen, which acts as a primary sporulation trigger. Avoid abrupt changes in media composition, as yeast cells require time to adapt to the stress conditions necessary for sporulation. For example, a two-step process—first growing cells in rich media (e.g., YPD) to log phase, then transferring to sporulation media—can enhance sporulation efficiency. Additionally, pH stability (around 5.5–6.5) is crucial, as fluctuations can disrupt the sporulation pathway.

Practical tips include using sterile techniques throughout the process to prevent contamination, which can derail sporulation. If working with mutant strains or less-studied yeast species, pilot experiments are invaluable for optimizing media composition and incubation parameters. For instance, some strains may require additional supplements, such as vitamins or trace metals, to support sporulation. Finally, document all conditions meticulously, as even minor variations can significantly impact sporulation success, making reproducibility a challenge.

In conclusion, the inoculation and incubation phase demands attention to detail, from inoculum size and media selection to temperature and agitation control. By creating a controlled environment that mimics natural stress conditions, researchers can reliably induce yeast sporulation, paving the way for applications in biotechnology, genetics, and beyond. Mastery of this step not only ensures high spore yields but also deepens our understanding of yeast’s remarkable adaptability to environmental challenges.

Milky Spore Effectiveness: A Proven Grub Control Solution for Lawns

You may want to see also

Harvest and Verify Spores: Collect spores via centrifugation and confirm sporulation using microscopy or staining

Spores are the resilient, dormant forms of yeast, crucial for long-term storage and stress resistance. Harvesting and verifying these spores is a precise process that ensures their viability and purity. Centrifugation is the go-to method for collecting spores from yeast cultures, effectively separating them from the liquid medium and cellular debris. This technique leverages the density difference between spores and other components, allowing for efficient isolation. Once collected, confirming sporulation is essential to ensure the success of the process. Microscopy and staining techniques provide visual evidence of spore formation, offering both qualitative and quantitative insights into the sporulation efficiency.

To begin the harvesting process, centrifuge the yeast culture at a controlled speed and duration. A typical protocol involves centrifuging at 3,000–4,000 × *g* for 10–15 minutes. This force is sufficient to pellet the spores without causing damage. After centrifugation, carefully aspirate the supernatant, leaving behind a concentrated spore suspension. For optimal results, resuspend the pellet in a sterile buffer, such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), to remove any residual medium components. This step ensures purity and prepares the spores for further analysis or storage.

Verification of sporulation is a critical step that demands precision. Microscopy, particularly phase-contrast or differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy, allows for direct observation of spores. Spores typically appear as refractile, oval structures within the yeast cells. For a more definitive confirmation, staining techniques like the Schaeffer-Fulton stain can be employed. This method differentially stains spores, making them easily distinguishable from vegetative cells. A successful stain will reveal spores as green or blue against a pink or red background, providing clear visual evidence of sporulation.

While centrifugation and microscopy are reliable, there are practical considerations to keep in mind. Over-centrifugation can lead to spore aggregation or damage, so adhere strictly to recommended speeds and durations. When using microscopy, ensure proper calibration and focus to avoid misinterpretation of results. For staining, follow the protocol meticulously, as deviations can affect the clarity of the outcome. Additionally, maintain sterile conditions throughout the process to prevent contamination, which could compromise the integrity of the spore sample.

In conclusion, harvesting and verifying yeast spores through centrifugation and microscopy or staining is a methodical process that combines technical skill with attention to detail. By following these steps, researchers can ensure the successful collection and confirmation of spores, paving the way for applications in biotechnology, food science, and beyond. This approach not only validates the sporulation process but also provides a foundation for further experimentation and innovation.

Can Botulinum Spores Enter the Body Through the Nose?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Preparing yeast cultures to create spores is essential for preserving yeast strains, studying their biology, or using them in industrial processes like fermentation. Spores are more resistant to environmental stresses, making them ideal for long-term storage and transportation.

Spore formation in yeast (specifically *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*) is typically induced by nutrient deprivation, particularly nitrogen depletion. Cultures are transferred to a sporulation medium (e.g., potassium acetate or acetate-based media) and incubated at optimal temperatures (25–30°C) for several days.

The time required for spore formation varies but generally takes 3–7 days. The process begins with the formation of asci (spore-containing sacs), and by day 5–7, most cells will have completed sporulation. Regular microscopic examination can confirm spore maturity.

Once spores are formed, the culture is centrifuged to separate spores from the medium. Spores are then washed, resuspended in a storage solution (e.g., water or glycerol), and stored at -80°C or in liquid nitrogen for long-term preservation. Glycerol acts as a cryoprotectant to maintain spore viability.