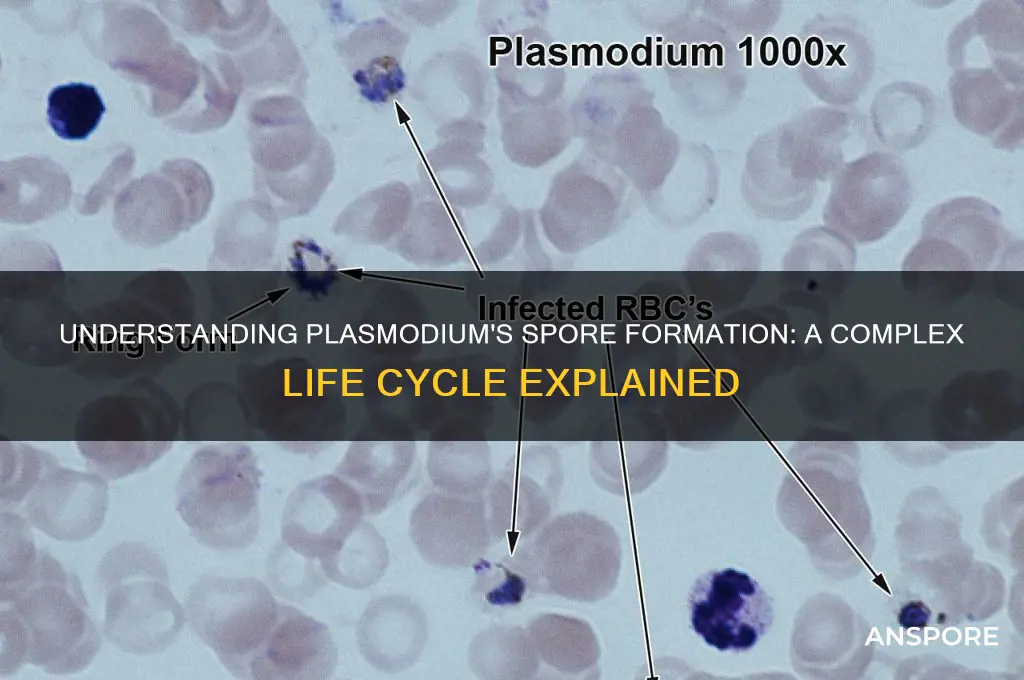

Plasmodium, the parasitic protozoan responsible for malaria, undergoes a complex life cycle involving both mosquito and vertebrate hosts. While plasmodium is primarily known for its asexual replication within red blood cells, it also undergoes a sexual phase in the mosquito vector, culminating in the formation of spores called oocysts. This process begins when male and female gametocytes, ingested by a mosquito during a blood meal, fuse to form a zygote within the mosquito's gut. The zygote then develops into an ookinete, which penetrates the gut wall and transforms into an oocyst. Within the oocyst, thousands of haploid spores called sporozoites are produced through multiple rounds of asexual division. Once mature, the oocyst ruptures, releasing sporozoites into the mosquito's hemolymph, which eventually migrate to the salivary glands, ready to be transmitted to a new vertebrate host during the mosquito's next blood meal. This sporulation process is critical for the parasite's transmission and survival, highlighting the intricate adaptations of plasmodium to its dual-host life cycle.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Organism Involved | Plasmodium (a genus of parasitic protozoans) |

| Life Cycle Stage | Sporogony (part of the sexual phase in the mosquito vector) |

| Location of Sporogony | Midgut and salivary glands of the female Anopheles mosquito |

| Initiation Trigger | Ingestion of male and female gametocytes by the mosquito during a blood meal |

| Gametocyte Activation | Triggered by changes in temperature, pH, and xanthurenic acid in the mosquito gut |

| Gamete Formation | Male gametocytes undergo exflagellation (produce 8 microgametes), female gametocytes form macrogametes |

| Fertilization | Microgamete fuses with macrogamete to form a zygote (ookinete) |

| Ookinete Development | Penetrates the mosquito midgut wall and transforms into an oocyst |

| Oocyst Growth | Undergoes multiple rounds of nuclear division (sporogony) to form sporozoites |

| Sporozoite Formation | Thousands of sporozoites develop within the oocyst |

| Oocyst Rupture | Mature oocyst ruptures, releasing sporozoites into the mosquito hemocoel |

| Migration to Salivary Glands | Sporozoites migrate to and invade the mosquito's salivary glands |

| Transmission | Sporozoites are injected into a new host during the mosquito's next blood meal |

| Duration of Sporogony | Typically 10-18 days, depending on the Plasmodium species and environmental conditions |

| Environmental Factors | Temperature and humidity significantly influence the sporogony process |

| Significance | Essential for the continuation of the Plasmodium life cycle and malaria transmission |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Sporogony initiation in oocyst

Sporogony, the process by which a plasmodium forms spores, begins within the oocyst, a critical stage in the life cycle of malaria-causing parasites. This initiation is triggered when a fertilized macrogamete, now called a zygote, undergoes a series of developmental changes inside the mosquito vector. The oocyst, formed on the mosquito’s midgut wall, serves as a protective environment for this transformation. Here, the zygote differentiates into a motile ookinete, which penetrates the midgut epithelium and establishes the oocyst. This marks the beginning of sporogony, a complex process that ultimately produces sporozoites, the infective forms of the parasite.

The initiation of sporogony in the oocyst is tightly regulated by environmental cues and genetic factors. Temperature, for instance, plays a pivotal role; optimal development typically occurs between 20°C and 28°C, with variations depending on the *Plasmodium* species. Below or above this range, the process slows or halts entirely. Additionally, the mosquito’s immune response must be evaded for successful oocyst formation. Parasites achieve this through molecular mimicry and immune modulation, ensuring the oocyst remains intact. Once established, the oocyst undergoes meiosis and multiple rounds of mitosis, giving rise to thousands of sporozoites. This proliferation is a testament to the parasite’s efficiency in exploiting its host environment.

From a practical standpoint, understanding sporogony initiation in the oocyst offers opportunities for intervention in malaria transmission. For example, targeting ookinete-to-oocyst transition or disrupting oocyst development could block sporozoite formation. Researchers have explored genetic modifications and chemical inhibitors to achieve this. One promising approach involves CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing to disable essential parasite genes during this stage. Alternatively, compounds like isoprenylcysteine analogs have shown potential in inhibiting oocyst growth. Such strategies, if integrated into mosquito control programs, could significantly reduce malaria transmission, particularly in high-burden regions.

Comparatively, sporogony initiation in the oocyst differs from other life cycle stages in its dependency on the mosquito vector. Unlike erythrocytic schizogony, which occurs in the human host, oocyst development is entirely mosquito-specific. This distinction highlights the importance of vector control in malaria eradication efforts. For instance, while antimalarial drugs target blood-stage parasites, interventions like insecticide-treated nets and genetic modifications in mosquitoes aim to disrupt sporogony. By focusing on this unique stage, researchers can develop more targeted and effective strategies to break the cycle of transmission.

In conclusion, sporogony initiation in the oocyst is a fascinating and critical process in the *Plasmodium* life cycle. It combines environmental sensitivity, genetic precision, and host-parasite interaction to ensure the parasite’s survival and transmission. By dissecting this stage, scientists gain insights into potential vulnerabilities that can be exploited for malaria control. Whether through genetic manipulation, chemical inhibition, or vector-based interventions, targeting sporogony initiation offers a promising avenue to combat this devastating disease. Understanding this process is not just an academic exercise—it’s a practical step toward a malaria-free future.

Are Magic Mushroom Spores Illegal in Ohio? Legal Insights

You may want to see also

Meiotic division process in sporoblast

The sporoblast, a critical structure in the life cycle of plasmodial slime molds, undergoes meiotic division to initiate spore formation. This process is a genetic bottleneck, ensuring genetic diversity through recombination and reducing the chromosome number by half. Meiotic division in the sporoblast begins with the replication of DNA during interphase, setting the stage for two rounds of cell division: meiosis I and meiosis II. Unlike mitosis, which maintains the chromosome number, meiosis is specifically tailored for sexual reproduction, producing haploid cells essential for spore development.

During meiosis I, homologous chromosomes pair up, exchange genetic material through crossing over, and then segregate into two daughter cells. This stage is crucial for genetic diversity, as crossing over shuffles alleles between homologous chromosomes. Prophase I, the longest phase, is particularly intricate, involving the formation of the synaptonemal complex and chiasmata, which stabilize the paired chromosomes. By the end of meiosis I, each daughter cell contains half the number of chromosomes as the parent sporoblast, but each chromosome still consists of two sister chromatids.

Meiosis II follows immediately, resembling mitosis but starting with haploid cells. Sister chromatids separate during anaphase II, resulting in four haploid cells, each with a single set of chromosomes. These cells will develop into spores, encased in protective walls that enable survival in harsh conditions. The entire meiotic process within the sporoblast is tightly regulated by enzymes like recombinases and cohesins, ensuring accurate chromosome segregation and recombination.

Practical observations of this process often involve staining techniques to visualize chromosomes during meiosis. For instance, fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) can highlight specific chromosome regions, aiding in the study of crossing over. Researchers also use time-lapse microscopy to track cell divisions in real-time, providing insights into the dynamics of sporoblast development. Understanding these mechanisms not only sheds light on slime mold biology but also offers comparative perspectives on meiotic processes across eukaryotes.

In summary, the meiotic division process in the sporoblast is a finely orchestrated sequence of events that ensures genetic diversity and prepares the groundwork for spore formation. From DNA replication to the final separation of sister chromatids, each step is critical for the survival and propagation of plasmodial species. By studying this process, scientists gain valuable tools and knowledge applicable to broader fields, including genetics, evolutionary biology, and even biotechnology.

Strong Spore Coats: Essential for Survival or Overrated Protection?

You may want to see also

Spore wall formation mechanism

The formation of a spore wall is a critical step in the life cycle of plasmodial organisms, particularly in slime molds like *Physarum polycephalum*. This process involves a series of intricate cellular and biochemical events that culminate in the creation of a protective barrier, ensuring the spore’s survival in harsh environmental conditions. Understanding this mechanism not only sheds light on the resilience of these organisms but also offers insights into broader biological processes such as cell differentiation and material science.

Analytical Perspective:

Spore wall formation begins with the differentiation of plasmodial cells into sporocarps, the structures that will eventually house the spores. This differentiation is triggered by environmental stressors such as nutrient depletion or desiccation. Within the sporocarp, the plasmodium undergoes a series of morphological changes, including the aggregation of cytoplasm and the reorganization of cellular components. Key to this process is the deposition of sporopollenin, a highly durable biopolymer that forms the primary component of the spore wall. Sporopollenin is synthesized through the polymerization of sporopollenin precursors, which are transported to the cell surface via vesicles. The precise mechanism of sporopollenin assembly remains a topic of research, but it is known to involve enzymes like polyketide synthases and peroxidases.

Instructive Approach:

To observe spore wall formation in a laboratory setting, researchers often use *Physarum polycephalum* as a model organism. Start by culturing the plasmodium on a nutrient agar plate until it reaches maturity. Induce sporulation by transferring the plasmodium to a non-nutrient substrate, such as a cellulose filter paper, and exposing it to controlled dehydration. Over 24–48 hours, the plasmodium will aggregate into sporocarps. To visualize the spore wall, fix the sporocarps in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution, stain with calcofluor white (which binds to chitin and other polysaccharides in the wall), and examine under a fluorescence microscope. This protocol allows for the detailed study of wall thickness, composition, and structural integrity.

Comparative Insight:

While the spore wall formation in plasmodial slime molds shares similarities with other spore-forming organisms like fungi and plants, there are notable differences. For instance, fungal spores often incorporate chitin as a major wall component, whereas plasmodial spores rely heavily on sporopollenin. Plant spores, such as those of ferns and mosses, also use sporopollenin but differ in the spatial organization of the wall layers. These variations highlight the evolutionary adaptations of spore-forming organisms to their specific ecological niches. By comparing these mechanisms, researchers can identify common principles and unique innovations in spore wall construction.

Descriptive Detail:

The mature spore wall is a marvel of natural engineering, typically consisting of three distinct layers: the exine, nexine, and intine. The exine, the outermost layer, is composed of sporopollenin and is responsible for the spore’s durability. Its sculptured surface, often adorned with spines or ridges, enhances resistance to abrasion and UV radiation. Beneath the exine lies the nexine, a thinner layer that provides structural support. The innermost intine, rich in polysaccharides, acts as a flexible membrane that maintains spore viability. Together, these layers create a robust yet lightweight structure capable of withstanding extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemical stressors, ensuring the spore’s longevity until favorable conditions for germination arise.

Practical Takeaway:

For educators and hobbyists interested in exploring spore wall formation, a simple experiment involves exposing *Physarum polycephalum* to varying environmental conditions to observe differences in sporulation. For example, compare sporocarp development under high humidity (90%) versus low humidity (40%) conditions. Document the time to sporulation, spore size, and wall thickness using basic microscopy. This hands-on approach not only deepens understanding of the mechanism but also highlights the plasmodium’s adaptability, making it an excellent teaching tool for biology and environmental science.

Parasect Panic Spores: Do Their Effects Stack in Battle?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Haploid sporozoite development stages

The life cycle of *Plasmodium*, the parasite responsible for malaria, is a complex journey involving multiple hosts and developmental stages. Among these, the formation of haploid sporozoites is a critical phase, marking the transition from the mosquito vector to the vertebrate host. This process begins within the mosquito’s midgut, where the parasite undergoes a series of transformations to produce the infectious sporozoites. Understanding these stages is essential for targeting interventions and disrupting the parasite’s life cycle.

Stage 1: Gametocyte Activation and Fertilization

Upon ingestion by a female *Anopheles* mosquito during a blood meal, male and female gametocytes—the sexual precursor cells—are activated by environmental cues such as temperature change and xanthurenic acid. Within minutes, male gametocytes undergo exflagellation, producing up to eight motile microgametes. These microgametes then fertilize female macrogametes, forming diploid zygotes. This rapid process is the first step in sporozoite development and highlights the parasite’s adaptability to its environment.

Stage 2: Ookinete Formation and Midgut Invasion

The zygote develops into an ookinete, a motile and invasive form, within 18–24 hours. The ookinete traverses the mosquito’s midgut epithelium, a critical step that requires secretion of proteases and other enzymes to degrade the midgut wall. Successful invasion allows the ookinete to reach the basal side of the midgut, where it encysts and transforms into an oocyst. This stage is a bottleneck in the parasite’s life cycle, as many ookinetes fail to penetrate the midgut, making it a potential target for intervention strategies.

Stage 3: Oocyst Maturation and Sporogony

Within the oocyst, multiple rounds of nuclear division (sporogony) occur, producing thousands of haploid sporozoites over 10–14 days. This asexual replication is a resource-intensive process, relying on nutrients from the mosquito and the oocyst wall. The oocyst eventually ruptures, releasing sporozoites into the mosquito’s hemolymph. These sporozoites migrate to the mosquito’s salivary glands, where they remain poised for transmission to a vertebrate host during the next blood meal.

Practical Implications and Interventions

Targeting haploid sporozoite development stages offers opportunities for malaria control. For instance, disrupting ookinete formation or oocyst maturation could prevent sporozoite production. Current research focuses on vaccines like RTS,S, which targets the circumsporozoite protein (CSP) on sporozoites, and genetic approaches such as gene drives to modify mosquito populations. Additionally, antimalarial drugs like primaquine, which target gametocytes, can reduce transmission by preventing fertilization. Understanding these stages not only advances scientific knowledge but also informs practical strategies to combat malaria.

Are Mold Spores Invisible? Unveiling the Hidden Truth About Mold

You may want to see also

Oocyst maturation and rupture

Within the intricate life cycle of Plasmodium, the oocyst plays a pivotal role in sporulation, a process critical for the parasite's transmission. Oocyst maturation and rupture are not merely passive events but highly regulated processes that ensure the parasite's survival and dissemination. This stage occurs within the mosquito vector, specifically in the midgut wall, where the oocyst undergoes a series of morphological and biochemical changes. Understanding these steps is essential for targeting interventions aimed at disrupting the parasite's life cycle.

Consider the timeline of oocyst maturation, which typically spans 10 to 14 days, depending on environmental factors such as temperature and humidity. During this period, the oocyst increases in size, accumulating nutrients and synthesizing proteins necessary for sporogony. The maturation process is marked by the development of sporoblasts, which eventually differentiate into sporozoites, the infectious forms of the parasite. Rupture of the mature oocyst releases these sporozoites into the mosquito's hemocoel, enabling their migration to the salivary glands, where they await transmission to a new host.

From a practical standpoint, disrupting oocyst maturation or rupture could be a strategic approach to malaria control. For instance, certain compounds, such as fungicides or plant-derived inhibitors, have shown potential in interfering with oocyst wall formation or integrity. Additionally, genetic modifications targeting enzymes involved in oocyst development could render the parasite incapable of completing this stage. Researchers are also exploring the use of Wolbachia bacteria, which can inhibit Plasmodium development within the mosquito, as a biological control method.

Comparatively, oocyst maturation in Plasmodium shares similarities with cyst formation in other parasites, such as Toxoplasma gondii, yet the mechanisms of rupture differ significantly. While Toxoplasma cysts remain dormant in tissues, Plasmodium oocysts must rupture to release sporozoites, highlighting the parasite's reliance on this event for transmission. This distinction underscores the importance of studying oocyst rupture as a unique and exploitable vulnerability in the Plasmodium life cycle.

In conclusion, oocyst maturation and rupture are dynamic processes that bridge the mosquito and vertebrate stages of Plasmodium's life cycle. By dissecting these mechanisms, researchers can identify novel targets for intervention, potentially leading to innovative strategies for malaria control. Whether through chemical inhibitors, genetic modifications, or biological agents, disrupting this critical stage holds promise for reducing the global burden of malaria.

Does Diphtheria Produce Spores? Unraveling the Bacteria's Survival Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A plasmodium is a multinucleate, amoeboid stage in the life cycle of slime molds, particularly in the class Myxomycetes. It forms spores as part of its reproductive process, typically when environmental conditions become unfavorable.

When conditions like food scarcity or desiccation occur, the plasmodium undergoes a process called fructification, where it transforms into a spore-bearing structure (e.g., a sporangium or sporocarp), eventually releasing spores.

Environmental stressors such as lack of food, drought, or temperature changes signal the plasmodium to initiate spore formation as a survival mechanism.

Spores are produced within the sporangium or sporocarp and are released when the structure matures and ruptures, dispersing the spores via wind, water, or other agents to colonize new habitats.

![Formation of Spores in the Sporanges of Rhizopus Nigricans / by Deane Bret Swingle 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)