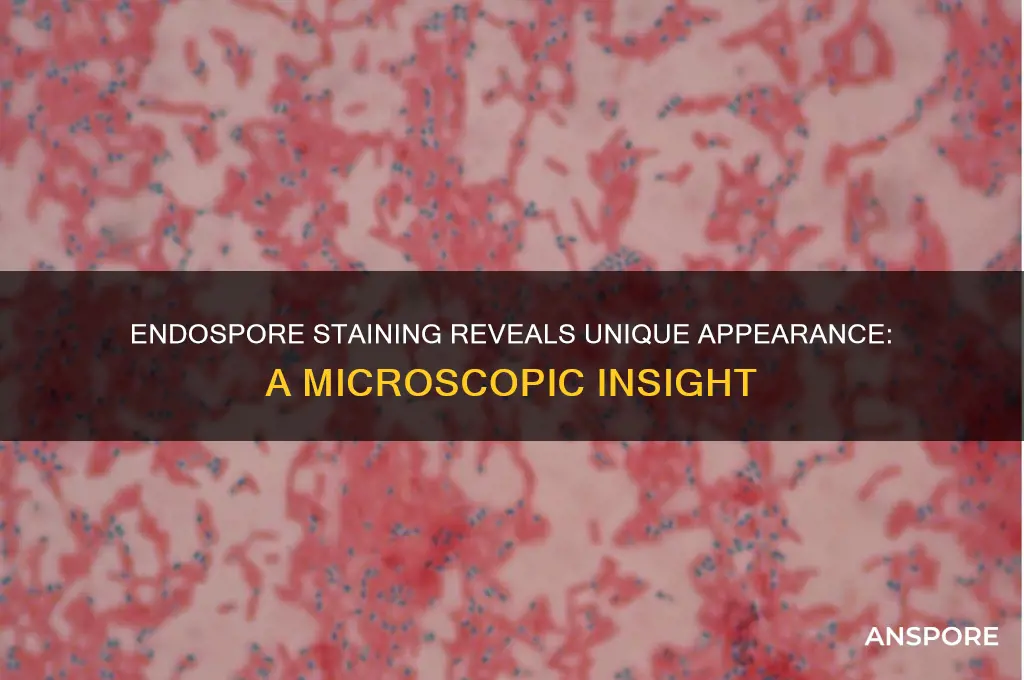

Endospores, highly resistant structures produced by certain bacteria, exhibit distinct characteristics when observed under a microscope after spore staining. Typically, the Schaeffer-Fulton stain is used, which differentially colors endospores green and the vegetative cell body red. When stained, an endospore appears as a small, refractile, oval or spherical body within the bacterial cell, often located centrally or at one end, giving the cell a drumstick appearance. The spore’s green color contrasts sharply with the red vegetative cell, making it easily identifiable. Its compact, dense structure and lack of staining in the surrounding cytoplasm highlight its resilience and dormant nature, distinguishing it from the more fragile, actively metabolizing parts of the bacterial cell.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Shape | Typically oval or round, but can vary depending on the bacterial species. |

| Size | Smaller than the vegetative bacterial cell, usually 0.5–1.5 μm in diameter. |

| Color | Appears as a distinct, refractile (greenish or bluish) body within the vegetative cell when stained with malachite green. |

| Location | Central or terminal within the bacterial cell, depending on the species (e.g., Bacillus spp. are central, Clostridium spp. are terminal). |

| Staining | Resistant to decolorization by water or alcohol, retaining the malachite green stain, while the vegetative cell counterstains pink or red with safranin. |

| Refractility | Highly refractile, appearing as a bright, almost glowing structure under a light microscope. |

| Wall Thickness | Thick, multilayered spore coat that contributes to its resistance and refractility. |

| Visibility | Clearly visible as a separate structure within the bacterial cell, often described as a "drumstick" appearance in Bacillus spp. |

| Decolorization Resistance | Does not decolorize during the staining process, unlike the vegetative cell wall. |

| Counterstain Appearance | The vegetative cell surrounding the endospore appears pink or red due to the safranin counterstain, while the endospore remains green. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Endospore morphology: Observe oval or round shape, central position, and refractile appearance under microscope after staining

- Spore stain process: Heat fixation, primary dye (malachite green), decolorizer, and counterstain (safranin) steps

- Refractility: Endospores appear bright, almost mirror-like, due to high refractive index after staining

- Size comparison: Endospores are smaller than vegetative cells, typically 0.5–1.5 μm in diameter

- Staining contrast: Endospores retain green color, while vegetative cells appear pink or red after counterstaining

Endospore morphology: Observe oval or round shape, central position, and refractile appearance under microscope after staining

Under the microscope, endospores reveal a distinct morphology that sets them apart from other bacterial structures. One of the most striking features is their oval or round shape, which contrasts with the often rod-shaped or coccoid forms of the vegetative bacterial cells. This uniformity in shape is a key identifier, especially when scanning a slide for these resilient structures. The endospore's geometry is not just a visual marker but also a functional adaptation, contributing to its durability and ability to withstand harsh conditions.

Central position is another critical characteristic. Endospores typically occupy a central location within the bacterial cell, often appearing as a bulge or a distinct body within the cytoplasm. This positioning is not arbitrary; it reflects the endospore's role as a survival mechanism. The central placement ensures that the endospore is protected by the surrounding cell wall and membrane, providing an additional layer of defense against environmental stressors. When stained, this central location becomes more pronounced, making it easier to distinguish the endospore from other cellular components.

The refractile appearance of endospores under the microscope is perhaps their most distinctive feature. This characteristic is due to the high density and unique composition of the endospore's outer layers, which cause light to bend or refract as it passes through. When stained with specific dyes, such as malachite green or safranin, the endospore appears as a bright, almost glowing, green or red structure against the lighter background of the vegetative cell. This refractility is not just a visual curiosity; it is a practical tool for microbiologists, allowing for quick and accurate identification of endospores in a sample.

To observe these features effectively, follow these steps: Prepare a bacterial smear on a clean slide, heat-fix it to adhere the cells to the glass, and stain using a differential staining technique like the Schaeffer-Fulton method. This process involves applying malachite green stain, heating to drive the dye into the endospores, and then counterstaining with safranin to color the vegetative cells. Examine the slide under oil immersion (1000X magnification), focusing on the shape, position, and refractility of the endospores. For best results, ensure the staining time is adequate (typically 5-10 minutes for malachite green) and the heat application is controlled to avoid over-staining or damaging the sample.

In comparison to other bacterial structures, endospores stand out not only for their morphology but also for their resilience. While vegetative cells may vary widely in shape and size, endospores maintain a consistent oval or round form, a central position, and a refractile appearance. This consistency is a testament to their specialized function as survival units. For educators and students, emphasizing these unique features during microscopy sessions can enhance understanding of bacterial adaptations and the importance of staining techniques in microbiology. By focusing on these specific morphological traits, one can quickly and accurately identify endospores, even in complex samples.

Does Metronome Spore Count Impact Mushroom Cultivation Success?

You may want to see also

Spore stain process: Heat fixation, primary dye (malachite green), decolorizer, and counterstain (safranin) steps

Endospores, the resilient dormant forms of certain bacteria, present a unique challenge in staining due to their impermeable nature. The spore stain process, a specialized technique, employs a series of steps to overcome this barrier and reveal these structures under a microscope. This process involves heat fixation, application of a primary dye (malachite green), decolorization, and counterstaining with safranin, each step meticulously designed to ensure accurate visualization.

Heat Fixation: The Crucial First Step

Heat fixation is the initial and critical step in the spore staining process. It serves a dual purpose: first, it firmly adheres the bacterial cells to the slide, preventing them from being washed away during subsequent steps. Second, and more importantly, the heat treatment begins to compromise the endospore's tough outer coat, making it more receptive to staining. This step typically involves passing the slide with the bacterial smear through a flame several times, ensuring even heating without scorching the sample.

Malachite Green: Penetrating the Endospore's Defense

Following heat fixation, the primary dye, malachite green, is applied. This dye is specifically chosen for its ability to penetrate the now slightly compromised endospore coat. The slide is steamed over the malachite green solution for a period of time, usually around 5 minutes. This steaming process further aids in forcing the dye into the endospore, ensuring thorough staining. The result is a deep green coloration of the endospores, setting them apart from the vegetative cells.

Decolorizer: Differentiating Endospores from Vegetative Cells

After staining with malachite green, a decolorizer, typically water or alcohol, is applied. This step is crucial for differentiation. The decolorizer washes away the malachite green from the vegetative cells, leaving them colorless. However, due to the endospore's unique structure and the previous heat treatment, the malachite green remains trapped within the endospore, resisting decolorization. This contrast allows for clear distinction between endospores and vegetative cells under the microscope.

Safranin Counterstain: Enhancing Contrast and Visibility

The final step involves counterstaining with safranin. This red dye stains the decolorized vegetative cells, providing a contrasting background that further highlights the green endospores. The safranin solution is applied for a brief period, typically 2-3 minutes, followed by a gentle wash to remove excess dye. The result is a clear and distinct image: green endospores standing out against a field of red vegetative cells, allowing for accurate identification and enumeration.

Oedogonium Filament Spores: Haploid or Diploid? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Refractility: Endospores appear bright, almost mirror-like, due to high refractive index after staining

Under the microscope, endospores stand out dramatically after staining, their surfaces reflecting light with a mirror-like intensity. This striking appearance is due to their high refractive index, a property that causes light to bend sharply as it passes through the spore’s dense, calcified outer layer. Unlike the surrounding bacterial cells, which absorb or scatter light, endospores act almost like tiny prisms, creating a bright, refractile glow. This phenomenon is not merely aesthetic; it serves as a critical diagnostic feature for microbiologists identifying spore-forming bacteria in clinical or environmental samples.

To observe this effect, a simple spore-staining technique, such as the Schaeffer-Fulton method, is employed. The process involves heating the bacterial smear with a primary stain (e.g., malachite green) to force the dye into the endospore, followed by a counterstain (e.g., safranin) to color the vegetative cell. The endospore’s high refractive index ensures that even under low magnification (400x–1000x), it appears as a distinct, bright green or blue dot against the pinkish-red background of the bacterial cell. This contrast is essential for distinguishing endospores from debris or artifacts in the sample.

The refractility of endospores is not just a visual curiosity but a survival mechanism. Their dense, multilayered structure, rich in calcium and dipicolinic acid, contributes to both their high refractive index and their resistance to extreme conditions. This same property that makes them visible under a microscope also helps them withstand heat, radiation, and desiccation, ensuring their longevity in harsh environments. Understanding this dual role of refractility bridges the gap between microbiology and the physics of light interaction with biological structures.

For practical applications, recognizing refractile endospores is crucial in fields like food safety, where spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* or *Bacillus cereus* can contaminate products. In clinical settings, identifying refractile spores in patient samples can indicate infections caused by *Clostridium difficile* or other spore-forming pathogens. To enhance visibility, ensure proper staining technique: maintain consistent heat application during the malachite green step (5–10 minutes at 80°C) and avoid over-decolorizing, as this can reduce the endospore’s refractility. With practice, the mirror-like glow of endospores becomes an unmistakable marker of their presence.

Can HEPA Filters Effectively Remove Mold Spores from Indoor Air?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Size comparison: Endospores are smaller than vegetative cells, typically 0.5–1.5 μm in diameter

Endospores, when viewed under a microscope after spore staining, present a striking contrast in size compared to their vegetative counterparts. Typically measuring between 0.5 and 1.5 μm in diameter, these resilient structures are notably smaller than the vegetative cells they originate from, which can range from 1 to 5 μm. This size difference is not merely a trivial detail but a critical adaptation that enhances their survival capabilities. The compact nature of endospores allows them to withstand extreme conditions, such as heat, desiccation, and chemicals, by minimizing surface area and maximizing internal protection.

To appreciate this size disparity, consider the staining process itself. When using a spore stain like the Schaeffer-Fulton method, the larger vegetative cells are easily distinguishable from the smaller, refractile endospores. The vegetative cells, often appearing as elongated or rod-shaped structures, dwarf the endospores, which typically appear as distinct, oval or spherical bodies within or adjacent to the cell. This visual contrast is a key diagnostic feature in identifying spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the size difference is essential for laboratory techniques. For instance, when calibrating microscopy equipment, knowing the expected size range of endospores (0.5–1.5 μm) helps ensure accurate identification and differentiation from other cellular components or contaminants. Additionally, this knowledge aids in optimizing staining protocols, as the smaller size of endospores requires precise control of staining time and reagent concentration to avoid over- or under-staining, which could obscure their visibility.

The size comparison also highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of endospores. Their reduced dimensions are not a limitation but a strategic advantage. Smaller size means less material to degrade, fewer targets for environmental damage, and greater ease in dispersal. This adaptation underscores why endospores are among the most durable life forms on Earth, capable of surviving for centuries in conditions that would destroy most other organisms. By focusing on this size difference, microbiologists gain deeper insights into the mechanisms of bacterial survival and the challenges of controlling spore-forming pathogens in clinical and industrial settings.

Can Aerobes Form Spores? Unveiling Microbial Survival Strategies

You may want to see also

Staining contrast: Endospores retain green color, while vegetative cells appear pink or red after counterstaining

Endospores, the resilient dormant forms of certain bacteria, exhibit a striking contrast when subjected to spore staining techniques. This contrast is particularly evident in the differential staining method known as the Schaeffer-Fulton stain, where endospores retain a distinct green color, while the surrounding vegetative cells take on a pink or red hue after counterstaining. This phenomenon is not merely a visual curiosity but a critical diagnostic feature in microbiology.

The process begins with the application of a primary stain, typically malachite green, which is forced into both the vegetative cells and the endospores through the use of heat or prolonged staining time. Malachite green has a strong affinity for the endospores due to their unique structure, which includes a thick, impermeable spore coat. This coat allows the dye to penetrate and remain trapped within the endospore, even after subsequent washing steps. In contrast, the vegetative cells, with their more permeable cell walls, retain less of the primary stain.

Following the primary staining, a decolorizer such as water or alcohol is applied to remove the malachite green from the vegetative cells, leaving them colorless. The endospores, however, retain the green stain due to the dye's strong binding. The final step involves counterstaining with a dye like safranin, which imparts a pink or red color to the decolorized vegetative cells. This counterstaining step not only highlights the vegetative cells but also enhances the contrast between them and the green endospores, making the latter easily identifiable under a microscope.

This staining contrast is not just a laboratory artifact but a reflection of the biological differences between endospores and vegetative cells. Endospores are designed to withstand extreme conditions, and their ability to retain the primary stain underscores their structural robustness. For microbiologists, this visual distinction is invaluable for identifying spore-forming bacteria in clinical, environmental, and industrial samples. For instance, in a clinical setting, the presence of green endospores within pink vegetative cells can quickly indicate a potential infection by spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridium* or *Bacillus*.

Practical tips for achieving optimal staining results include ensuring the heat fixation step is adequate to allow malachite green penetration without overheating the slide, which can cause the endospores to lose their distinctive green color. Additionally, the decolorization step should be carefully timed to avoid over-decolorizing, which could lead to false-negative results. By mastering this staining technique, microbiologists can leverage the unique staining contrast to accurately identify and study endospores, contributing to both diagnostic precision and scientific understanding.

Breathing C. Diff Spores: Risks, Prevention, and Air Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

An endospore typically appears as a small, refractile (light-refracting), oval or round body within the bacterial cell, often with a distinct green or blue color depending on the staining method used.

The endospore is much smaller, more intensely stained, and appears as a distinct, separate structure within the larger, less-stained vegetative cell.

In a standard endospore staining procedure, such as the Schaeffer-Fulton method, the endospore stains green, while the vegetative cell stains red.

Endospores appear refractile due to their high density and low water content, which causes light to bend as it passes through them, making them stand out against the surrounding medium.

Yes, endospores can sometimes be confused with air bubbles or debris, but their consistent size, shape, and staining characteristics (e.g., green color in Schaeffer-Fulton stain) help distinguish them.