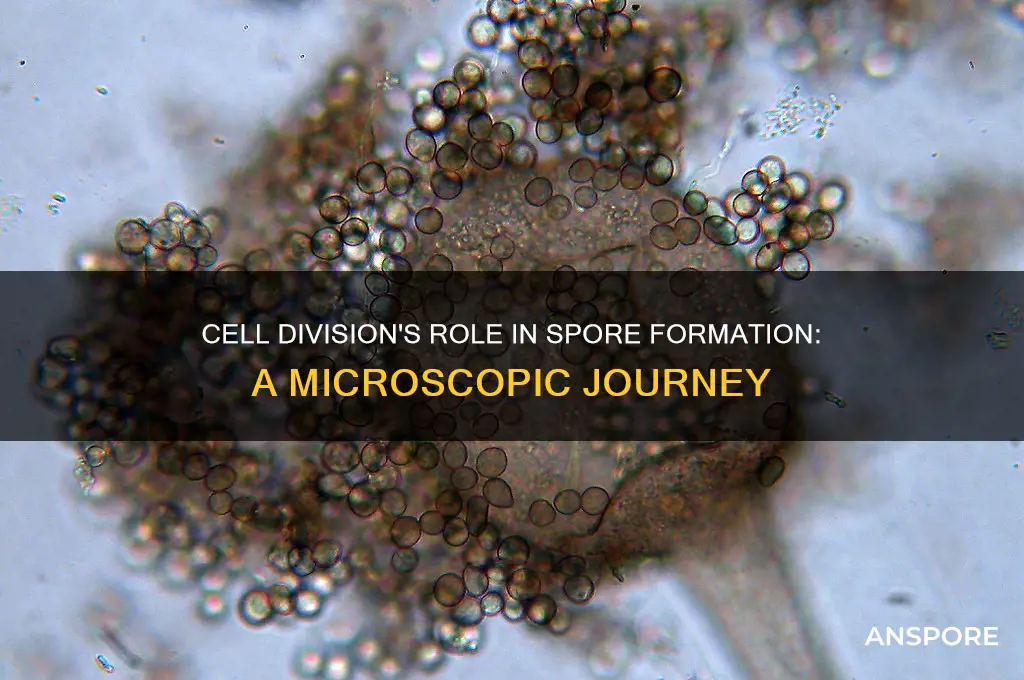

Cell division plays a crucial role in the production of spores, which are specialized reproductive structures found in various organisms such as fungi, plants, and some bacteria. In spore-producing organisms, specific types of cell division, particularly meiosis, are employed to generate spores. Meiosis involves two rounds of nuclear division, resulting in the formation of four haploid cells, each containing half the genetic material of the parent cell. This process ensures genetic diversity among spores. Following meiosis, additional mitotic divisions may occur to increase the number of spores produced. The resulting spores are typically encased in protective structures, allowing them to survive harsh environmental conditions and disperse to new habitats, where they can germinate and grow into new individuals.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process Type | Asexual reproduction |

| Cell Division Type | Meiosis (in most cases, though some organisms use mitosis) |

| Parent Cell | Sporocyte (spore-producing cell) |

| Daughter Cells | Spores (haploid cells) |

| Genetic Variation | High (due to meiosis and genetic recombination) |

| Wall Formation | Spores develop thick, protective walls (e.g., sporopollenin in plants, chitin in fungi) |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to environmental stresses (e.g., heat, desiccation, radiation) |

| Dormancy | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods until favorable conditions arise |

| Dispersal | Spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, water, or animals |

| Examples of Organisms | Fungi (e.g., molds, mushrooms), Plants (e.g., ferns, mosses), Bacteria (e.g., endospores in Bacillus) |

| Function | Survival in harsh conditions, colonization of new habitats, and long-distance dispersal |

| Energy Efficiency | Highly efficient for survival, as spores require minimal resources during dormancy |

| Nucleus State | Haploid (n) in most spores, though some fungi produce diploid spores |

| Size | Typically smaller than the parent cell, optimized for dispersal and resistance |

| Metabolic Activity | Minimal or absent during dormancy, reactivating upon germination |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation initiation: Environmental triggers like nutrient depletion or stress activate specific genes to start spore formation

- Asymmetric cell division: Unequal divisions create a small forespore and larger mother cell during sporulation

- Spore maturation: The forespore develops a protective coat and dehydrates for long-term survival

- Mother cell role: The mother cell engulfs the forespore, providing nutrients and protection during development

- Spore release: Mature spores are released when the mother cell lyses, dispersing them into the environment

Sporulation initiation: Environmental triggers like nutrient depletion or stress activate specific genes to start spore formation

In the microbial world, survival often hinges on the ability to adapt to harsh conditions. When nutrients become scarce or environmental stressors mount, certain bacteria and fungi initiate a remarkable transformation: sporulation. This process is not a random act but a highly regulated response, triggered by specific environmental cues that activate a cascade of genetic events. For instance, in *Bacillus subtilis*, nutrient depletion, particularly the limitation of carbon and nitrogen sources, acts as a primary signal for the cell to divert its energy towards spore formation. This is not merely a passive reaction but a strategic decision encoded in the organism’s DNA, ensuring its long-term survival.

Consider the step-by-step mechanism behind this initiation. When nutrients fall below a critical threshold, the cell detects this change through signaling pathways such as the phosphorylation cascade involving kinases like Spo0A. In *B. subtilis*, Spo0A acts as a master regulator, accumulating in its active form when nutrients are depleted. Once activated, Spo0A binds to specific DNA sequences, upregulating genes essential for sporulation while downregulating those involved in vegetative growth. This genetic switch is precise and efficient, ensuring that the cell allocates resources to spore formation rather than futile attempts at continued growth. For researchers or biotechnologists, understanding this pathway can inform strategies for inducing sporulation in controlled environments, such as optimizing nutrient concentrations in fermentation processes.

A comparative analysis highlights the diversity of sporulation triggers across species. While nutrient depletion is a universal cue, the specific stressors and genetic responses vary. In fungi like *Aspergillus*, oxidative stress or exposure to reactive oxygen species (ROS) can initiate sporulation, with genes like *osm-1* playing a critical role in sensing and responding to these conditions. In contrast, *Streptomyces* bacteria respond to phosphate limitation by activating the *pho* regulon, which includes genes necessary for spore development. This diversity underscores the adaptability of sporulation as a survival strategy, tailored to the unique challenges faced by each organism. For practical applications, such as developing antifungal agents, targeting these stress-responsive pathways could disrupt spore formation and limit pathogen spread.

Persuasively, the study of sporulation initiation offers more than academic insight—it has tangible implications for industries ranging from agriculture to medicine. For example, understanding how environmental stressors trigger sporulation in plant pathogens like *Fusarium* could lead to novel crop protection strategies. By manipulating nutrient availability or inducing specific stresses, farmers might suppress spore formation and reduce disease transmission. Similarly, in biotechnology, controlling sporulation in beneficial microbes could enhance their use in probiotics or biofertilizers. A key takeaway is that sporulation is not an inevitable process but a manipulable one, governed by predictable genetic and environmental interactions.

Descriptively, the initiation of sporulation is a symphony of cellular responses orchestrated by environmental cues. Imagine a bacterial cell sensing the gradual exhaustion of its food supply, its metabolic machinery slowing as it prepares for dormancy. Within its nucleus, genes once silent spring to life, their activation a testament to the cell’s resilience. This transformation is not just a survival tactic but a marvel of biological engineering, where stress becomes the catalyst for renewal. For anyone studying or working with microbes, recognizing these triggers and their genetic underpinnings opens doors to harnessing sporulation for both scientific discovery and practical innovation.

Humidity's Role in Activating Mold Spores: What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Asymmetric cell division: Unequal divisions create a small forespore and larger mother cell during sporulation

Asymmetric cell division is a finely tuned process that underpins sporulation in certain organisms, notably bacteria like *Bacillus subtilis*. Unlike symmetric division, which produces two identical daughter cells, asymmetric division creates a size disparity: one cell becomes the small, genetically identical forespore, while the other remains the larger mother cell. This unequal partitioning is not arbitrary; it’s a strategic survival mechanism. The forespore, though diminutive, is primed for endurance, equipped with a thick, protective coat to withstand harsh conditions. The mother cell, meanwhile, assumes a nurturing role, synthesizing nutrients and protective molecules before ultimately lysing to release the mature spore.

Consider the steps involved in this process, a molecular choreography orchestrated by proteins like SpoIIE and SpoIIIE. First, the cell divides asymmetrically, positioning the forespore near one pole. SpoIIE anchors to the septum, ensuring proper localization of future spore-specific structures. Next, SpoIIIE facilitates DNA translocation from the mother cell to the forespore, guaranteeing the forespore receives a complete genome. This phase is critical: any misstep in DNA partitioning can render the forespore nonviable. Concurrently, the mother cell synthesizes spore-specific proteins, such as coat layers and peptidoglycan, which are transported to the forespore via specialized channels.

A cautionary note: asymmetric division’s precision is both its strength and vulnerability. Environmental stressors, like nutrient deprivation or temperature fluctuations, can disrupt the process. For instance, mutations in genes encoding division proteins (e.g., *minCDE* or *soj*) can lead to symmetric division, aborting sporulation. Similarly, antibiotics targeting cell wall synthesis (e.g., penicillin) can interfere with septum formation, halting the process mid-stream. Researchers often exploit these vulnerabilities to study sporulation, using genetic knockouts or chemical inhibitors to dissect the pathway.

Practically, understanding asymmetric division has tangible applications. In biotechnology, spores of *Bacillus* species are used as probiotics, biocontrol agents, and enzyme producers. Optimizing sporulation efficiency—by manipulating division proteins or environmental conditions—can enhance yields. For example, increasing manganese (Mn^2+) concentration in growth media has been shown to promote asymmetric division, as Mn^2+ activates key sporulation sigma factors. Conversely, in medicine, disrupting sporulation in pathogens like *Clostridioides difficile* could prevent spore-mediated infections, a leading cause of hospital-acquired diarrhea.

In conclusion, asymmetric cell division is a masterclass in cellular resource allocation. By producing a small, resilient forespore and a larger, sacrificial mother cell, organisms ensure genetic continuity in adverse conditions. This process, while intricate, is not infallible, and its vulnerabilities offer both research opportunities and practical interventions. Whether in biotechnology or medicine, the principles of asymmetric division provide a blueprint for manipulating cellular fate—a testament to nature’s ingenuity and our growing ability to harness it.

Understanding the Fascinating Process of Plant Spore Production and Dispersal

You may want to see also

Spore maturation: The forespore develops a protective coat and dehydrates for long-term survival

During spore maturation, the forespore undergoes a remarkable transformation, preparing itself for long-term survival in harsh environments. This process involves two critical steps: the development of a protective coat and dehydration. The coat, composed of multiple layers of proteins and polymers, acts as a barrier against physical damage, UV radiation, and desiccation. Simultaneously, the forespore expels water, reducing its metabolic activity to a near-dormant state, which enables it to withstand extreme conditions such as heat, cold, and chemical exposure. This dual strategy ensures that the spore remains viable for years, even decades, until conditions become favorable for germination.

Consider the example of *Bacillus subtilis*, a bacterium that forms endospores. During maturation, the forespore synthesizes a coat made of over 70 different proteins, each contributing to its resilience. The outermost layer, known as the exosporium, provides additional protection against environmental stressors. Dehydration is equally crucial; the water content of a mature spore drops to as low as 10-20% of its dry weight, significantly slowing down chemical reactions that could degrade its DNA or proteins. This combination of a robust coat and extreme desiccation allows *Bacillus* spores to survive in soil, water, and even outer space.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore maturation has significant implications for industries such as food preservation and medicine. For instance, food manufacturers must ensure that spores of bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* are completely eradicated, as their protective coats make them highly resistant to heat and preservatives. Techniques such as high-pressure processing (HPP) or irradiation are often employed to break through the spore coat and inactivate the organism. Conversely, in biotechnology, spores’ durability is harnessed for the long-term storage of genetically modified organisms or vaccines, where maintaining viability over extended periods is essential.

A comparative analysis reveals that spore maturation strategies vary across species, reflecting their ecological niches. Fungal spores, for example, develop walls rich in chitin, a tough polysaccharide, whereas bacterial spores rely on proteinaceous coats. Despite these differences, the underlying principle remains the same: invest energy in creating a protective structure and reducing metabolic vulnerability. This evolutionary convergence underscores the effectiveness of spore maturation as a survival mechanism. By studying these variations, scientists can develop targeted methods to control unwanted spores or enhance the resilience of beneficial ones.

In conclusion, spore maturation is a finely tuned process that ensures the long-term survival of organisms in adverse conditions. The development of a protective coat and dehydration work in tandem to create a nearly indestructible form. Whether in the context of microbial control or biotechnological applications, understanding this process provides valuable insights into combating or leveraging spores’ remarkable durability. For anyone working with microorganisms, appreciating the intricacies of spore maturation is not just academic—it’s practical knowledge that can inform strategies for preservation, eradication, or utilization.

Are Rhizopus Spores Visible? Unveiling the Microscopic Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mother cell role: The mother cell engulfs the forespore, providing nutrients and protection during development

In the intricate process of spore formation, the mother cell plays a pivotal role that is both nurturing and protective. Imagine a scenario where a single cell takes on the responsibility of safeguarding and nourishing its offspring, ensuring their survival in harsh conditions. This is precisely what happens during endospore formation in certain bacteria, such as *Bacillus subtilis*. The mother cell engulfs the developing forespore, creating a microenvironment that shields it from external stressors like heat, desiccation, and chemicals. This engulfment is not merely a passive process but a highly regulated event, akin to a parent cradling a child, providing a sanctuary for growth and maturation.

Analyzing this mechanism reveals a fascinating interplay of cellular machinery. Once the forespore is engulfed, the mother cell’s membrane envelops it, forming a double-layered structure known as the sporulation septum. This compartmentalization allows the mother cell to selectively transfer nutrients, such as amino acids and nucleotides, to the forespore while retaining its own structural integrity. For instance, in *Bacillus* species, the mother cell synthesizes and donates peptidoglycan precursors to the forespore, which are essential for building its protective cortex layer. This nutrient transfer is tightly controlled, ensuring the forespore receives just enough resources to develop without depleting the mother cell’s reserves. Think of it as a carefully calibrated feeding schedule, optimized for the forespore’s developmental needs.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the mother cell’s role has significant implications for biotechnology and medicine. For example, spores of *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, rely on this protective mechanism to survive in the environment for decades. By studying how the mother cell nurtures the forespore, researchers can develop strategies to disrupt spore formation, potentially leading to new antimicrobial therapies. Similarly, in industrial applications, spores of *Bacillus* species are used in probiotics and enzyme production. Optimizing spore yield and viability could enhance these processes, and the mother cell’s role is a critical factor in this optimization.

Comparatively, the mother cell’s function in spore formation contrasts with other forms of cell division, such as binary fission, where offspring cells are immediately independent. Here, the mother cell sacrifices its own longevity to ensure the forespore’s survival, often lysing after the spore matures. This altruistic behavior underscores the evolutionary advantage of spores: they are nature’s time capsules, preserving genetic material until conditions improve. For instance, soil-dwelling bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* rely on this mechanism to endure extreme environments, highlighting the mother cell’s indispensable role in their life cycle.

In conclusion, the mother cell’s engulfment of the forespore is a masterclass in cellular cooperation and resource management. It provides a protective cocoon, a nutrient pipeline, and a developmental blueprint, all within a tightly orchestrated process. Whether you’re a microbiologist studying spore biology or an industry professional optimizing spore-based products, appreciating this mechanism offers valuable insights. By focusing on the mother cell’s role, we unlock a deeper understanding of how cell division produces spores—a process that has sustained life on Earth for billions of years.

Can Spores Travel on Paper? Uncovering the Hidden Risks

You may want to see also

Spore release: Mature spores are released when the mother cell lyses, dispersing them into the environment

The final act of spore production is a dramatic one: the mother cell, having nurtured and protected its spore progeny, sacrifices itself. This process, known as lysis, involves the rupture of the mother cell's membrane, releasing the mature spores into the surrounding environment. It's a one-way ticket to freedom for the spores, but a death sentence for the cell that created them. This mechanism ensures efficient dispersal, allowing spores to travel on air currents, water, or even animal fur, seeking new habitats to colonize.

Imagine a tiny, pressurized chamber bursting open, propelling its contents outward. This is essentially what happens during spore release. The mother cell's wall weakens and eventually ruptures, a process triggered by various factors depending on the organism. In some fungi, for instance, environmental cues like nutrient depletion or changes in temperature signal the time for release. This lytic release mechanism is a key adaptation for spore-producing organisms, enabling them to propagate and survive in diverse and often harsh conditions.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this release process is crucial in fields like agriculture and medicine. For farmers, knowing when and how spores are dispersed can inform strategies to control plant diseases caused by fungal pathogens. For example, if a particular fungus releases spores at dawn, targeted fungicide applications at this time could be more effective. In medicine, studying spore release mechanisms can aid in developing strategies to prevent the spread of spore-forming pathogens, such as certain bacteria that cause food poisoning.

The lysis of the mother cell is a precise and coordinated event, ensuring the successful dispersal of spores. This process highlights the intricate balance between cellular sacrifice and the continuation of the species. By studying these mechanisms, scientists can unlock new ways to control and utilize spore-producing organisms, from enhancing crop protection to developing novel biotechnological applications. Understanding the final stage of spore production provides valuable insights into the remarkable strategies employed by nature for survival and propagation.

Ants' Role in Invertebrate-Mediated Spore Dispersal of Phallus Fungi

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The process by which cell division produces spores is typically through a specialized type of cell division called meiosis, followed by sporulation. In organisms like fungi, plants (e.g., ferns, mosses), and some protists, meiosis reduces the chromosome number, creating haploid cells. These cells then undergo sporulation, where they develop protective walls to form spores, which can disperse and germinate under favorable conditions.

Meiosis contributes to spore production by ensuring genetic diversity and reducing the chromosome number. During meiosis, a diploid cell undergoes two rounds of division, producing four haploid cells. These haploid cells then develop into spores. This reduction in chromosome number is essential for the life cycle of many organisms, allowing for alternation between haploid and diploid phases, and promoting genetic variation through recombination.

Organisms such as fungi, plants (e.g., ferns, mosses, and some algae), and certain protists produce spores through cell division. Spores serve as a means of survival, dispersal, and reproduction. They are highly resistant to harsh environmental conditions, allowing the organism to persist through unfavorable periods. Once conditions improve, spores can germinate and grow into new individuals, ensuring the continuation of the species.

![Formation of Spores in the Sporanges of Rhizopus Nigricans / by Deane Bret Swingle 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)