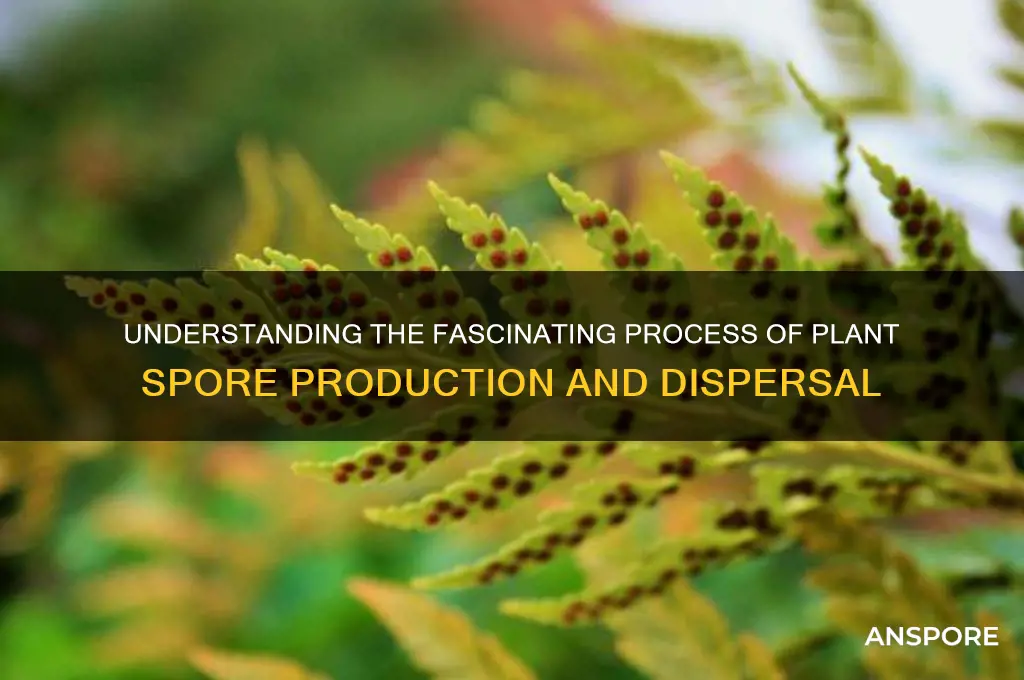

Plant spores are produced through a specialized reproductive process that occurs in the life cycles of ferns, mosses, fungi, and some other plant groups. In most cases, spores are generated through a process called sporogenesis, which takes place within structures like sporangia. These sporangia are typically located on the underside of fern fronds or within the capsules of mosses. Inside the sporangia, diploid cells undergo meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, producing haploid spores. Once mature, these spores are released into the environment, often aided by wind or water, to disperse and germinate under suitable conditions, eventually growing into new individuals. This asexual method of reproduction allows plants to thrive in diverse environments and ensures their survival across generations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Production Site | Sporangia (specialized structures within sporangium) |

| Cell Division | Meiosis (reduction division) |

| Sporangium Types | Microsporangia (produce microspores/pollen) and megasporangia (produce megaspores) |

| Sporophyte Generation | Spores are produced by the diploid sporophyte generation |

| Spore Types | Haploid (contain half the number of chromosomes as the parent plant) |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Wind, water, animals, or explosive mechanisms |

| Germination | Spores germinate under suitable conditions to form gametophytes |

| Gametophyte Generation | Gametophytes produce gametes (sperm and egg) for sexual reproduction |

| Life Cycle | Alternation of generations between sporophyte and gametophyte phases |

| Examples | Ferns, mosses, fungi, and some seedless vascular plants |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporangia Development: Specialized structures called sporangia form on plants to produce and contain spores

- Meiosis in Spores: Spores are produced through meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity in offspring

- Types of Spores: Plants produce different spore types, such as microspores and megaspores, for reproduction

- Environmental Triggers: Factors like light, moisture, and temperature influence spore production and release

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are dispersed via wind, water, or animals to reach new habitats

Sporangia Development: Specialized structures called sporangia form on plants to produce and contain spores

Spores are the microscopic units through which many plants reproduce, and their production hinges on the development of specialized structures called sporangia. These sac-like organs are the factories where spores are formed, nurtured, and eventually released into the environment. Found in ferns, mosses, and fungi, sporangia are a testament to nature’s ingenuity in ensuring species survival. Their formation is a tightly regulated process, influenced by genetic, environmental, and developmental cues, making them a fascinating subject in plant biology.

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a prime example of sporangia in action. On the underside of mature fern fronds, clusters of sporangia, known as sori, develop. Each sporangium is a capsule lined with a layer of cells that undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores. The process begins with the differentiation of sporogenous cells, which divide to form spore mother cells. These cells then undergo meiosis, resulting in the production of four haploid spores per mother cell. The sporangium wall, composed of specialized layers, provides protection and support during spore maturation. This intricate process ensures that each spore is equipped to survive harsh conditions and germinate when favorable conditions return.

The development of sporangia is not just a biological curiosity but a critical adaptation for plant survival. Unlike seeds, spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, water, or animals, allowing plants to colonize new habitats efficiently. For instance, mosses produce sporangia atop slender stalks called setae, elevating the spores for optimal dispersal. In fungi, sporangia often rupture explosively, propelling spores into the air. This diversity in sporangium structure and function highlights their role as evolutionary marvels, tailored to the specific needs of each organism.

Practical observation of sporangia can be a rewarding activity for botanists and enthusiasts alike. To examine sporangia, collect mature fern fronds and use a magnifying glass to locate the sori. Gently pressing a piece of clear tape onto the sori and transferring it to a microscope slide allows for detailed inspection of the sporangia and spores. For fungi, look for spore-bearing structures like the gills of mushrooms or the undersides of molds. Understanding sporangia development not only deepens appreciation for plant diversity but also informs conservation efforts, as many spore-producing plants are indicators of ecosystem health.

In conclusion, sporangia are the unsung heroes of plant reproduction, encapsulating the complexity and elegance of nature’s design. Their development is a finely tuned process that ensures the continuity of species across diverse environments. By studying sporangia, we gain insights into the mechanisms of plant survival and the interconnectedness of life on Earth. Whether in a laboratory or a forest, exploring sporangia offers a window into the microscopic world that sustains our planet.

Where to Locate Your Spore CD Key on Steam: A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

Meiosis in Spores: Spores are produced through meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity in offspring

Spores, the microscopic units of plant reproduction, are not merely clones of their parent organisms. Instead, they are products of meiosis, a specialized cell division process that ensures genetic diversity in offspring. Unlike mitosis, which produces genetically identical cells, meiosis involves two rounds of division, halving the chromosome number and shuffling genetic material through crossing over. This process results in spores with unique genetic combinations, a critical factor for plant adaptation and survival in changing environments.

Consider the life cycle of ferns, a prime example of spore-producing plants. Within the fern’s reproductive structures (sporangia), diploid spore mother cells undergo meiosis to form haploid spores. Each spore, carrying half the genetic material of its parent, can develop into a gametophyte—a small, independent plant. This gametophyte then produces gametes (sperm and eggs) through mitosis, ensuring that the next generation inherits a blend of genetic traits from both parents. Without meiosis, ferns and other spore-producing plants would lack the genetic variability needed to thrive in diverse habitats, from tropical rainforests to arid deserts.

From a practical standpoint, understanding meiosis in spore production has significant implications for horticulture and conservation. For instance, orchid growers often exploit this process to breed new varieties with desirable traits, such as vibrant colors or unique shapes. By controlling the conditions under which spores germinate and gametophytes develop, growers can encourage specific genetic combinations. Similarly, conservationists use knowledge of meiosis to preserve endangered plant species, ensuring that reintroduced populations retain sufficient genetic diversity to withstand diseases and climate change.

Comparatively, meiosis in spore production contrasts sharply with seed production in flowering plants. While seeds develop from fertilized eggs and retain the diploid chromosome number, spores are haploid and must undergo further development to produce gametes. This distinction highlights the evolutionary advantage of spores: their smaller size and lighter weight allow for wind or water dispersal, enabling plants to colonize new areas efficiently. However, this advantage comes with the challenge of relying on external conditions for fertilization, underscoring the importance of genetic diversity in ensuring successful reproduction.

In conclusion, meiosis is the cornerstone of spore production, driving genetic diversity that is essential for plant survival and evolution. Whether in the delicate fronds of a fern or the vibrant blooms of an orchid, this process ensures that each spore carries a unique genetic blueprint. For gardeners, scientists, and conservationists alike, appreciating the role of meiosis in spore production offers valuable insights into plant biology and practical strategies for cultivation and preservation. By harnessing this knowledge, we can foster healthier, more resilient plant populations for generations to come.

Can Spores Travel on Paper? Uncovering the Hidden Risks

You may want to see also

Types of Spores: Plants produce different spore types, such as microspores and megaspores, for reproduction

Plants, in their quest for survival and propagation, have evolved a sophisticated reproductive strategy centered around spores. Among these, microspores and megaspores stand out as the primary players in the reproductive cycle of seed plants, particularly in gymnosperms and angiosperms. Microspores, smaller in size, develop into pollen grains, which are essential for fertilization. Megaspores, larger and fewer in number, give rise to the female gametophyte, housing the egg cell. This division of labor ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, showcasing nature’s ingenuity in balancing efficiency with resilience.

Consider the process of microspore formation in angiosperms, where it begins within the anther of a flower. Microsporocytes, or pollen mother cells, undergo meiosis to produce four haploid microspores. Each microspore then matures into a pollen grain through a series of developmental stages, including the formation of a protective exine layer. This process is not just a biological curiosity; it’s a critical step in ensuring successful pollination. For gardeners, understanding this can inform practices like hand-pollination in greenhouses or selecting plants with robust pollen production for hybridization.

In contrast, megaspore development is a more intricate affair, often involving the selection of a single functional megaspore from a tetrad. In angiosperms, this occurs within the ovule, where a megasporocyte undergoes meiosis. Typically, three of the resulting megaspores degenerate, leaving one to develop into the female gametophyte. This gametophyte, though microscopic, is a powerhouse of reproductive potential, containing the egg cell that will eventually fuse with a sperm from a pollen grain. For botanists and breeders, studying megaspore development can reveal insights into seed viability and genetic inheritance.

The distinction between microspores and megaspores isn’t just about size; it’s about their roles in the reproductive economy of plants. Microspores are produced in vast quantities, increasing the odds of successful fertilization, while megaspores are fewer but more resource-intensive, reflecting the higher investment in the female reproductive structure. This asymmetry is a strategic adaptation, ensuring that plants maximize their reproductive output while conserving energy. For educators, this provides a compelling example of evolutionary trade-offs in biology lessons.

Practical applications of understanding spore types extend beyond academia. In agriculture, for instance, knowledge of microspore and megaspore development can improve crop yields through optimized pollination techniques or the selection of varieties with superior spore production. In conservation efforts, it aids in the propagation of endangered plant species through techniques like spore banking. Whether you’re a hobbyist gardener or a professional botanist, recognizing the unique roles of microspores and megaspores offers a deeper appreciation of the intricate mechanisms driving plant reproduction.

Angiosperms: Seed Producers or Spore Creators? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Triggers: Factors like light, moisture, and temperature influence spore production and release

Light, a silent conductor, orchestrates the timing of spore production in many plant species. Photoperiod, the duration of light exposure, acts as a crucial signal. For instance, ferns often initiate spore development during longer daylight hours, a phenomenon known as photoperiodism. This adaptation ensures spores are released when conditions are optimal for germination and growth. Interestingly, specific wavelengths of light, particularly red and far-red, can differentially influence spore formation. Red light, mimicking sunlight, promotes sporulation in some mosses, while far-red light, indicative of shading, may suppress it. Understanding these light-driven mechanisms allows horticulturists to manipulate photoperiods and light spectra in controlled environments, optimizing spore yield for research or conservation purposes.

Moisture, the lifeblood of spore dispersal, plays a dual role in spore production. While excessive moisture can hinder spore maturation by promoting fungal growth, a certain level of humidity is essential for spore development and release. In liverworts, for example, spore capsules require a humid environment to swell and eventually burst, dispersing spores. Conversely, some desert-adapted plants, like certain species of Selaginella, have evolved to produce spores in response to brief periods of increased moisture, capitalizing on ephemeral water availability. This delicate balance highlights the importance of precise moisture control in cultivating spore-producing plants, whether in natural habitats or laboratory settings.

Temperature acts as a thermostat, fine-tuning the pace of spore production and release. Cooler temperatures often slow down metabolic processes, delaying spore maturation, while warmer temperatures accelerate them. However, extreme heat can be detrimental, causing desiccation and inhibiting spore viability. For instance, certain orchid species require a specific temperature range to trigger spore formation within their seed pods. This temperature sensitivity underscores the need for careful monitoring and regulation in spore cultivation, especially for species with narrow thermal tolerances.

The interplay of light, moisture, and temperature creates a complex environmental symphony that dictates spore production and release. These factors do not act in isolation; rather, they synergistically influence plant physiology. For example, optimal spore production in some ferns requires a combination of long daylight hours, moderate humidity, and warm temperatures. Recognizing these interdependencies allows for the creation of tailored environments that maximize spore yield, whether for botanical research, ecological restoration, or horticultural endeavors. By manipulating these environmental triggers, we can unlock the full potential of spore-producing plants, ensuring their survival and propagation in a changing world.

Sterilization vs. Bacterial Spores: Does It Effectively Kill Them All?

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores are dispersed via wind, water, or animals to reach new habitats

Spores, the microscopic units of plant reproduction, are not merely produced—they are engineered for travel. Their dispersal mechanisms are as varied as the environments they inhabit, each tailored to maximize the chances of reaching new habitats. Wind, water, and animals serve as the primary vehicles, each offering unique advantages and challenges. Understanding these mechanisms reveals the ingenuity of nature’s design in ensuring plant survival and propagation.

Consider wind dispersal, the most common method for spore travel. Plants like ferns and mushrooms release spores into the air, relying on their lightweight structure and aerodynamic shape to carry them over vast distances. For instance, a single fern can release millions of spores in a single season, each capable of floating for miles. To optimize this process, plants often produce spores in elevated structures, such as the undersides of fern leaves or the gills of mushrooms, ensuring they catch the slightest breeze. Practical tip: If you’re cultivating spore-producing plants indoors, place them near a window to encourage natural airflow and enhance dispersal.

Water dispersal, while less common, is equally fascinating. Aquatic plants like certain algae and liverworts release spores into water currents, allowing them to travel downstream to colonize new areas. These spores are often encased in protective layers to withstand the rigors of aquatic environments. For example, the spores of the water fern *Azolla* are buoyant and can remain viable in water for extended periods. If you’re managing a pond or aquarium, introducing water-dispersed spores can promote biodiversity, but monitor their growth to prevent overcolonization.

Animal-mediated dispersal adds an element of unpredictability to spore travel. Plants like certain mosses and lichens produce spores that adhere to animal fur or feathers, hitching a ride to distant locations. This method is particularly effective for reaching isolated habitats, such as islands or mountain peaks. For instance, the spores of the lichen *Usnea* are easily carried by birds, enabling them to colonize trees far from their parent organism. To encourage this mechanism in a garden setting, incorporate animal-friendly features like bird baths or small ponds, which attract creatures that can inadvertently transport spores.

Each dispersal mechanism highlights the adaptability of spore-producing plants. Wind offers range, water provides consistency, and animals introduce randomness—all critical for survival in diverse ecosystems. By studying these mechanisms, we gain insights into the delicate balance between plant reproduction and environmental interaction. Whether you’re a gardener, ecologist, or simply a nature enthusiast, understanding spore dispersal can deepen your appreciation for the intricate strategies plants employ to thrive.

Does Killing Powdery Mildew Release Spores? Understanding the Risks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Plant spores are microscopic, single-celled reproductive units produced by plants, primarily in ferns, mosses, and fungi. They are typically generated through a process called sporogenesis, which occurs in specialized structures like sporangia. In this process, cells within the sporangium undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores.

Ferns produce spores on the undersides of their fronds in structures called sori. Each sorus contains numerous sporangia, where sporocytes undergo meiosis to form haploid spores. When mature, the sporangia release the spores, which can disperse via wind or water to grow into new plants.

In mosses, spores are produced in a capsule called the sporophyte, which grows from the gametophyte (the green, leafy part). The sporophyte releases spores through a structure called the peristome. In ferns, spores are produced on the undersides of mature fronds in sori, and the process is more integrated into the visible plant structure. Both rely on sporogenesis but differ in the location and mechanism of spore release.

![Formation of Spores in the Sporanges of Rhizopus Nigricans / by Deane Bret Swingle 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)