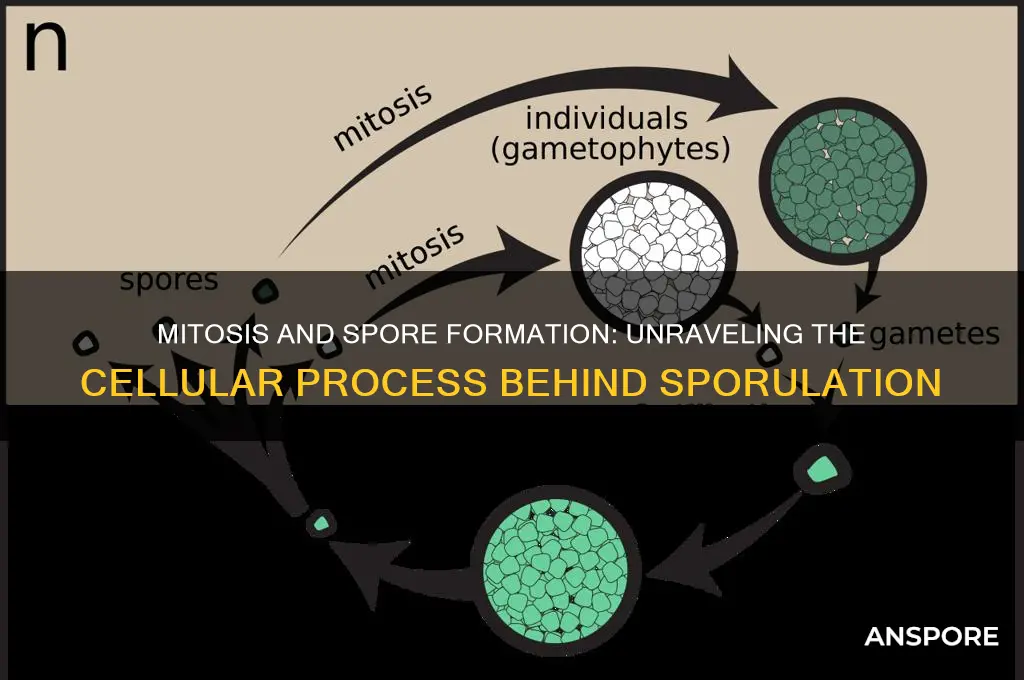

Mitosis plays a crucial role in the production of spores, particularly in organisms like fungi, plants, and some algae, through a specialized process called sporulation. During sporulation, a parent cell undergoes mitosis to create genetically identical daughter cells, which then develop into spores. In fungi, for example, mitosis occurs within sporangia, where the nucleus divides repeatedly, followed by the partitioning of cytoplasm to form individual spores. This process ensures that each spore carries a complete set of chromosomes, allowing it to grow into a new organism under favorable conditions. In plants, mitosis is involved in the formation of spores in structures like sporangia in ferns or pollen sacs in seed plants. By producing spores through mitosis, organisms can efficiently disperse and survive in diverse environments, ensuring their reproductive success and adaptability.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process | Mitosis is a type of cell division that results in two genetically identical daughter cells, each with the same number of chromosomes as the parent cell. |

| Spores | Spores are haploid cells produced by certain organisms, such as fungi, plants, and some protozoa, as a means of asexual reproduction or dispersal. |

| Mitosis in spore production | In some organisms, like fungi, mitosis is involved in the production of spores, specifically during the formation of sporocytes (spore-forming cells). |

| Sporocyte formation | A diploid cell (2n) undergoes meiosis to form a haploid sporocyte (n), which then undergoes mitosis to produce multiple haploid spores. |

| Spore types | Mitosis is involved in the production of asexual spores, such as conidia in fungi or gemmae in liverworts, rather than sexual spores (e.g., zygospores or ascospores). |

| Fungal spore production | In fungi like Aspergillus or Penicillium, mitosis occurs within the sporocyte to produce a chain of haploid spores (conidia) that are released for dispersal. |

| Plant spore production | In plants like ferns or mosses, mitosis is involved in the production of haploid spores within the sporangia, which are then released for germination. |

| Genetic identity | Since mitosis produces genetically identical daughter cells, the spores formed through this process are clones of the parent cell, maintaining genetic uniformity. |

| Dispersal and survival | Spores produced through mitosis are often lightweight, durable, and capable of surviving harsh environmental conditions, facilitating dispersal and colonization. |

| Examples | Fungi (conidia), liverworts (gemmae), and some algae produce spores through mitosis as a means of asexual reproduction and dispersal. |

| Advantages | Mitosis-driven spore production allows for rapid multiplication, genetic stability, and efficient dispersal, enhancing the organism's survival and adaptability. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation in Mitosis: Mitosis creates spores through cell division, ensuring genetic uniformity in offspring

- Role of Sporangia: Sporangia house spore-producing cells, facilitating mitotic division for spore release

- Genetic Consistency: Mitosis maintains identical DNA in spores, preserving species traits accurately

- Environmental Triggers: External factors like stress or nutrient scarcity initiate spore production via mitosis

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Mitosis-produced spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals for colonization

Spore Formation in Mitosis: Mitosis creates spores through cell division, ensuring genetic uniformity in offspring

Mitosis, a fundamental process of cell division, plays a pivotal role in spore formation, particularly in organisms like fungi and plants. Unlike meiosis, which involves genetic recombination, mitosis ensures that each daughter cell is genetically identical to the parent cell. This uniformity is crucial for spores, as it guarantees that each spore carries the same genetic material, preserving the organism's traits across generations. In fungi, for example, mitotic division produces spores such as conidia, which are asexual reproductive units. These spores are essentially clones of the parent, allowing for rapid and efficient propagation in stable environments.

The process begins with the parent cell undergoing mitosis, where the nucleus divides into two identical nuclei, followed by the division of the cytoplasm. In spore-forming organisms, this division is often localized to specific structures, such as sporangia in fungi or sporophylls in plants. For instance, in the bread mold *Rhizopus*, mitotic divisions within the sporangium produce haploid spores that are genetically identical to the parent. This method ensures that the spores are ready to develop into new individuals without the need for fertilization, streamlining reproduction in favorable conditions.

One of the key advantages of spore formation through mitosis is its efficiency in resource utilization. Since the process does not involve the energy-intensive recombination seen in meiosis, organisms can produce large numbers of spores quickly. This is particularly beneficial in environments where rapid colonization is essential, such as in nutrient-rich substrates or after disturbances. For example, ferns release thousands of genetically identical spores, each capable of growing into a new plant under suitable conditions. This strategy maximizes the organism's chances of survival and expansion.

However, the genetic uniformity of mitotically produced spores also has limitations. In changing environments, the lack of genetic diversity can make populations vulnerable to diseases or environmental stresses. To mitigate this, some organisms employ mechanisms like mutation or horizontal gene transfer to introduce variability. For instance, certain fungi can undergo parasexual cycles, where genetic recombination occurs without meiosis, providing a middle ground between uniformity and diversity.

In practical terms, understanding spore formation through mitosis has significant applications in agriculture, biotechnology, and medicine. For example, the production of genetically uniform spores in fungi is exploited in the cultivation of mushrooms, ensuring consistent yield and quality. Similarly, in plant breeding, controlling spore formation can enhance crop resilience and productivity. By manipulating the conditions under which mitosis occurs, scientists can optimize spore production for various purposes, from food production to the development of bio-based materials.

In conclusion, mitosis-driven spore formation is a remarkable mechanism that balances efficiency and uniformity in reproduction. While it offers advantages in stable environments, its limitations highlight the importance of genetic diversity in long-term survival. By studying this process, we gain insights into the strategies organisms use to thrive and tools to harness these mechanisms for human benefit.

Are Mildew Spores Dangerous? Understanding Health Risks and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Role of Sporangia: Sporangia house spore-producing cells, facilitating mitotic division for spore release

Sporangia, often likened to miniature factories, are the specialized structures where the magic of spore production unfolds. These sac-like organs house the spore mother cells, which undergo mitotic division to create spores. Imagine a bustling workshop where raw materials are transformed into finished products—sporangia function similarly, orchestrating the precise division of genetic material to ensure each spore is a viable unit for dispersal and growth. This process is not merely a biological curiosity but a cornerstone of survival for many organisms, particularly in the plant and fungal kingdoms.

Consider the lifecycle of ferns, a prime example of sporangia in action. On the underside of fern fronds, clusters of sporangia, called sori, develop. Within each sporangium, spore mother cells divide through mitosis, producing numerous haploid spores. This division is critical because it ensures genetic diversity while maintaining the organism’s ability to reproduce efficiently. For instance, a single fern sporangium can release up to 1,000 spores, each capable of growing into a new plant under favorable conditions. This high output is essential for ferns, which often inhabit environments where dispersal is challenging.

The role of sporangia extends beyond housing spore-producing cells; they also provide a protective environment for mitotic division. This is particularly important in fungi, where sporangia shield the developing spores from environmental stressors like desiccation or predation. For example, in the bread mold *Rhizopus*, sporangia form at the tips of stalks, creating a safe space for spores to mature. Once mature, the sporangium wall ruptures, releasing the spores into the environment. This timed release mechanism ensures that spores are dispersed when conditions are optimal for survival and germination.

Practical applications of understanding sporangia and mitotic spore production are evident in agriculture and biotechnology. For instance, farmers cultivating spore-producing crops like mushrooms rely on controlled environments to optimize sporangial development. By manipulating factors like humidity and temperature, growers can enhance spore yield and quality. Similarly, in biotechnology, researchers study sporangial mitosis to develop techniques for genetic modification or disease resistance in spore-producing organisms. For hobbyists growing ferns indoors, ensuring adequate light and moisture can stimulate sporangium formation, leading to successful spore release and propagation.

In conclusion, sporangia are not just passive containers but dynamic hubs of mitotic activity, driving the production and release of spores. Their role is both protective and productive, ensuring the continuity of species through efficient dispersal mechanisms. Whether in the wild or in controlled settings, understanding sporangia offers insights into the intricate balance of nature and opportunities for innovation in various fields. By appreciating their function, we gain a deeper respect for the microscopic processes that underpin life’s diversity.

Effective Ways to Eliminate Black Mold Spores in Your Home

You may want to see also

Genetic Consistency: Mitosis maintains identical DNA in spores, preserving species traits accurately

Mitosis, a fundamental process of cell division, ensures that each new cell receives an exact copy of the parent cell's DNA. This precision is particularly critical in spore production, where genetic consistency is paramount. Spores, whether produced by fungi, plants, or certain protozoa, serve as survival structures that must retain the species' unique traits to ensure successful germination and growth. Without the fidelity of mitosis, genetic variations could compromise the spore's ability to function as intended, potentially leading to evolutionary drift or reduced fitness.

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a plant that relies on spores for reproduction. During sporophyte development, specialized structures called sporangia undergo mitosis to produce haploid spores. Each spore carries a single set of chromosomes identical to those of the parent plant, thanks to the error-free replication and distribution of DNA during mitosis. This genetic consistency ensures that when a spore germinates into a gametophyte, it retains the species' characteristic traits, such as leaf shape, size, and resistance to environmental stressors. For example, a fern species adapted to low-light conditions will produce spores that, upon germination, develop into gametophytes with the same shade tolerance, ensuring survival in its specific habitat.

The importance of genetic consistency extends beyond individual survival to ecological stability. In fungal species like *Aspergillus*, mitosis during spore formation ensures that each spore carries the same genetic blueprint, including traits for nutrient absorption and antibiotic production. This uniformity allows fungal populations to maintain their role in ecosystems, such as decomposing organic matter or forming symbiotic relationships with plants. Deviations in genetic consistency could disrupt these functions, leading to imbalances in nutrient cycling or reduced plant health.

Practical applications of this genetic fidelity are evident in agriculture and biotechnology. For instance, crop plants like wheat and rice produce spores (pollen grains) through mitosis, ensuring that each grain carries the desired traits of the parent plant. Farmers and breeders rely on this consistency to maintain high-yielding, disease-resistant varieties. Similarly, in biotechnology, mitosis is harnessed to produce genetically identical spores for use in fermentation processes, such as in the production of antibiotics or enzymes. Ensuring genetic consistency at this stage is critical, as even minor variations can affect product quality and yield.

In summary, mitosis plays a pivotal role in maintaining genetic consistency during spore production, a trait essential for preserving species characteristics and ensuring ecological and practical applications. By faithfully replicating and distributing DNA, mitosis guarantees that spores retain the unique traits of their parent organisms, from ferns in shaded forests to fungi in laboratory bioreactors. This precision underscores the evolutionary advantage of mitosis and its continued relevance in both natural and human-directed processes.

Inoculating Live Oak Trees: Exploring the Potential of Spore Treatment

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Triggers: External factors like stress or nutrient scarcity initiate spore production via mitosis

In the natural world, organisms often respond to environmental pressures by activating survival mechanisms. For certain species, particularly fungi and plants, one such mechanism is the production of spores through mitosis. External stressors like nutrient scarcity or physical damage act as triggers, signaling the need for rapid reproduction and dispersal. This process ensures the organism’s genetic continuity even in adverse conditions. For example, when a fungus detects a lack of essential nutrients, it shifts its energy toward spore formation, a strategy that allows it to persist until more favorable conditions arise.

Consider the steps by which environmental triggers initiate spore production. When a plant or fungus senses stress, such as drought or overcrowding, it activates specific genes that regulate mitotic cell division. This division results in the formation of spores, which are lightweight, durable, and capable of surviving harsh environments. In fungi, this process often occurs in specialized structures like sporangia, where cells undergo mitosis to produce thousands of spores. For plants, stress-induced spore production is less common but can be observed in certain bryophytes and ferns, where environmental cues like temperature fluctuations or light changes prompt spore development.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these triggers can inform agricultural and conservation efforts. For instance, farmers can manipulate environmental conditions to encourage spore production in beneficial fungi, enhancing soil health and crop resilience. In laboratory settings, researchers use controlled stress factors, such as nutrient-limited media or temperature shifts, to study spore formation in fungi like *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*. By mimicking natural stressors, scientists can optimize spore yields for biotechnological applications, such as enzyme production or biocontrol agents.

Comparatively, the role of stress in spore production highlights a broader evolutionary strategy: adaptability. While animals often respond to stress through migration or behavioral changes, sessile organisms like plants and fungi rely on reproductive adaptations. Spores, produced via mitosis, serve as a dispersal mechanism, allowing the organism to colonize new habitats or survive until conditions improve. This contrast underscores the diversity of survival strategies in the biological world, each tailored to the organism’s ecological niche.

In conclusion, environmental triggers like stress or nutrient scarcity act as critical initiators of spore production via mitosis. By responding to these cues, organisms ensure their survival in challenging conditions. Whether in natural ecosystems or controlled environments, understanding these mechanisms offers practical applications in agriculture, biotechnology, and conservation. This knowledge not only deepens our appreciation of biological adaptability but also provides tools to harness these processes for human benefit.

Do Gas Masks Effectively Filter Spores? A Comprehensive Analysis

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Mitosis-produced spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals for colonization

Spores produced through mitosis are nature's ingenious solution for survival and propagation, but their success hinges on effective dispersal. Once formed, these microscopic units of life must escape their parent organism to colonize new habitats. Wind, water, and animals emerge as the primary agents of this journey, each offering distinct advantages and challenges. Wind dispersal, for instance, allows spores to travel vast distances, but it is unpredictable and relies on favorable conditions. Water dispersal, on the other hand, provides a more directed path, especially in aquatic or humid environments, though it limits range to connected waterways. Animal dispersal, often facilitated by spores adhering to fur or feathers, combines mobility with the potential for long-distance transport, albeit with less control over destination.

Consider the practicalities of wind dispersal. Spores adapted for this mechanism are typically lightweight and aerodynamic, often featuring structures like wings or tails. For example, ferns release spores with a four-armed structure that catches air currents, enabling them to float over considerable distances. To maximize wind dispersal, organisms often elevate their spore-bearing structures, such as the tall stalks of mushrooms or the raised fronds of ferns. Gardeners and conservationists can mimic this by placing spore-producing plants in open, elevated areas where air movement is unimpeded. However, wind dispersal is most effective in open landscapes, making it less suitable for dense forests or urban environments.

Water dispersal, while less glamorous, is remarkably efficient in the right context. Aquatic plants like mosses and certain algae release spores that are buoyant and can travel along currents, ensuring colonization of downstream habitats. Even terrestrial plants in wet environments, such as liverworts, exploit this mechanism. For those cultivating water-dispersed species, ensuring access to flowing water—whether natural streams or artificial irrigation systems—is crucial. A cautionary note: spores dispersed by water are vulnerable to desiccation if stranded on dry land, so maintaining moisture levels is essential during the dispersal phase.

Animal dispersal introduces an element of unpredictability but offers unparalleled opportunities for colonization. Spores may attach to an animal's body through hooks, sticky substances, or sheer abundance, as seen in the dusty spores of certain fungi. This method is particularly effective for reaching isolated or distant habitats, such as islands or mountain ranges. To encourage animal dispersal, consider planting spore-producing species near animal pathways or in areas frequented by wildlife. However, this strategy requires patience, as success depends on the movements of unpredictable carriers.

In conclusion, the dispersal of mitosis-produced spores is a multifaceted process that leverages the strengths of wind, water, and animals. Each mechanism has its niche, and understanding these can inform strategies for propagation, conservation, or even pest control. Whether you're a gardener aiming to spread ferns, a conservationist restoring wetlands, or a researcher studying fungal ecosystems, tailoring your approach to the dispersal mechanism at play can significantly enhance outcomes. By harnessing these natural processes, we can facilitate the colonization of new habitats and ensure the survival of spore-producing organisms in diverse environments.

Trading as a Military City Spore: Strategies and Possibilities Explored

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mitosis is a type of cell division that results in two genetically identical daughter cells. In spore-producing organisms like fungi and plants, mitosis is involved in the formation of spores, ensuring each spore contains a complete set of chromosomes.

Organisms such as fungi (e.g., molds and yeasts), ferns, and some algae use mitosis to produce spores. In these organisms, mitosis ensures the genetic material is accurately copied and distributed during spore formation.

Mitosis produces genetically identical spores with the same chromosome number as the parent cell, while meiosis produces genetically diverse spores with half the chromosome number. Mitosis is used for asexual spore production, whereas meiosis is used for sexual spore production.

The crucial stages are prophase (chromosomes condense), metaphase (chromosomes align at the equator), anaphase (chromatids separate), and telophase (nuclear membranes reform). These stages ensure accurate distribution of genetic material into spores.

Mitosis ensures that each spore receives a complete and identical set of genetic material, allowing for rapid and efficient reproduction. This process helps spore-producing organisms survive in diverse environments and disperse widely.