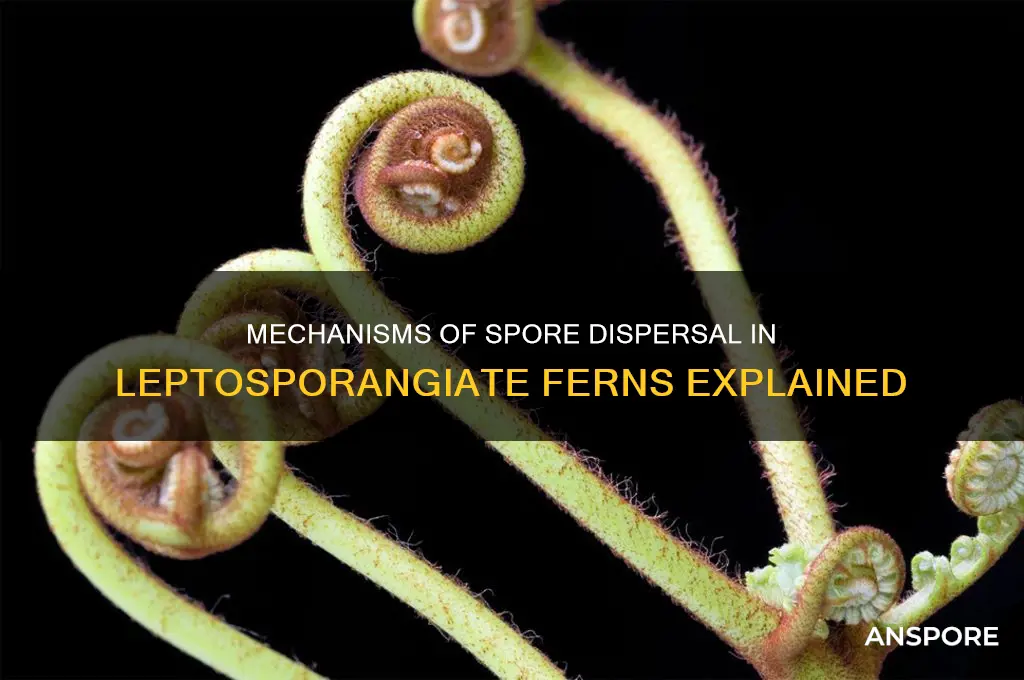

Spore dispersal in leptosporangiate ferns, the most diverse group of ferns, is a fascinating process that ensures the survival and propagation of these plants. Leptosporangiate ferns produce spores within structures called sporangia, which are typically located on the undersides of their fronds. When mature, these sporangia undergo a series of dehydration-induced changes, causing them to explosively release spores into the surrounding environment. This mechanism, known as ballistospory, relies on the rapid movement of a ring-shaped annulus around the sporangium, which propels spores over short distances. Additionally, wind and water play crucial roles in dispersing spores further afield, allowing leptosporangiate ferns to colonize new habitats and maintain their widespread distribution across diverse ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spore Type | Leptosporangiate ferns produce monolete spores (single-lined spores). |

| Spore Size | Typically small, ranging from 20 to 60 micrometers in diameter. |

| Spore Wall Structure | Composed of two layers: an inner delicate layer and an outer sculptured layer with ridges or spines, aiding in dispersal. |

| Spore Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are released through annulus-driven mechanisms in the sporangium. |

| Annulus Function | The annulus (a ring of thickened cells) dries out and contracts, causing the sporangium to open explosively, ejecting spores. |

| Dispersal Distance | Spores can travel short to moderate distances, depending on wind conditions and spore morphology. |

| Environmental Factors | Wind, humidity, and temperature influence spore dispersal efficiency. |

| Spore Longevity | Spores can remain viable in the environment for extended periods, aiding in colonization of new habitats. |

| Adaptations for Dispersal | Spore surface sculpturing (e.g., ridges, spines) reduces friction and enhances wind capture. |

| Role of Sporangium Position | Sporangia are typically located on the underside of fertile fronds, optimizing spore release into the air. |

| Reproductive Strategy | Leptosporangiate ferns rely on spore dispersal for asexual reproduction and colonization of new areas. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Wind-mediated spore dispersal mechanisms in leptosporangiate ferns

- Role of sporangium structure in efficient spore release

- Hydrodynamic factors influencing fern spore dispersal in moist environments

- Gravity and ballistic forces in short-distance spore dispersal

- Adaptations of indusium and annulus in spore ejection processes

Wind-mediated spore dispersal mechanisms in leptosporangiate ferns

Leptosporangiate ferns, the most diverse group of ferns, have evolved sophisticated wind-mediated spore dispersal mechanisms to ensure their survival and propagation. These mechanisms are finely tuned to maximize the distance and efficiency of spore dispersal, leveraging the unpredictable nature of wind currents. One key feature is the annulus, a ring of cells around the sporangium that functions like a spring. As the sporangium dries, the annulus contracts, forcibly ejecting spores into the air. This ballistic mechanism, combined with the lightweight nature of spores, allows them to be carried over significant distances, even in gentle breezes.

Consider the indusium, a protective covering found in some leptosporangiate ferns, such as those in the genus *Dryopteris*. While it may seem counterintuitive for spore dispersal, the indusium actually aids the process by creating a microenvironment that enhances spore release. As the indusium curls back, it exposes the sporangia to air currents, facilitating their dehydration and subsequent spore ejection. This dual-purpose structure highlights the ferns' adaptability in optimizing wind dispersal without compromising spore protection during development.

To understand the effectiveness of these mechanisms, examine the spore morphology of leptosporangiate ferns. Spores are typically 20–60 micrometers in diameter, with a low mass-to-surface area ratio, enabling them to remain suspended in air for longer periods. Additionally, many spores possess surface structures like perines or wings, which increase their aerodynamic properties. For instance, the tetrahedral shape of *Polypodium* spores reduces air resistance, allowing them to travel farther than spherical spores of similar size.

Practical observations of wind-mediated dispersal can be made in the field. Position yourself downwind from a mature fern colony during dry, breezy conditions, and you’ll notice a faint dusting of spores settling on surfaces. To study this further, collect spores using a glass slide coated in petroleum jelly, placed 1–2 meters away from the ferns. Over 30 minutes, you’ll observe a visible accumulation of spores, demonstrating their dispersal range. For more precise measurements, use a portable anemometer to correlate wind speed with spore density at varying distances.

In conclusion, the wind-mediated spore dispersal mechanisms of leptosporangiate ferns are a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. From the spring-like annulus to the protective yet functional indusium, every feature is designed to harness wind currents effectively. By studying these adaptations, we gain insights into the ecological strategies of ferns and their ability to thrive in diverse environments. Whether you’re a botanist, ecologist, or nature enthusiast, observing these mechanisms firsthand offers a deeper appreciation for the complexity of plant reproduction.

How to Register an EA Account for Spore: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Role of sporangium structure in efficient spore release

The sporangium of a leptosporangiate fern is a marvel of evolutionary engineering, designed to maximize spore dispersal with minimal energy expenditure. This kidney-shaped structure, typically 0.5–1.0 mm in length, is attached to the fern's leaf-like frond by a slender stalk. Its wall consists of a single layer of cells that gradually dehydrate, creating a built-in tension mechanism. As these cells lose moisture, they pull apart along a specific line called the annulus, forming a slit-like opening. This design ensures that spore release is not only efficient but also highly responsive to environmental cues, such as humidity and temperature changes.

Consider the annulus as the sporangium’s release valve. Composed of 1–3 rows of thick-walled cells, it acts like a spring-loaded mechanism. When the surrounding air is dry, the annulus cells contract, widening the sporangium’s opening and ejecting spores with surprising force. This process, known as "ballistic spore discharge," can propel spores up to 10–20 cm away from the parent plant. For comparison, this distance is equivalent to a human jumping over a three-story building—a remarkable feat for a microscopic structure. Such precision in design highlights the sporangium’s role as a finely tuned dispersal tool rather than a passive container.

To optimize spore release, gardeners and fern enthusiasts should mimic the natural conditions that trigger the annulus mechanism. For indoor ferns, maintain a humidity level of 40–60% and ensure good air circulation to encourage dehydration of the sporangium wall. Avoid overwatering, as excessive moisture can delay or inhibit spore discharge. For outdoor cultivation, plant ferns in areas with partial shade and well-draining soil to replicate their native woodland habitats. Observing the sporangia under a magnifying glass during dry periods can reveal the annulus in action, providing both educational insight and practical feedback on environmental conditions.

While the sporangium’s structure is inherently efficient, its success in spore dispersal also depends on its position on the fern. Sporangia are clustered into groups called sori, often located on the underside of mature fronds. This strategic placement ensures spores are released downward, taking advantage of gravity and air currents. For those propagating ferns from spores, collect sori when they turn brown—a sign the sporangia are mature. Gently tap the frond over a sheet of paper to release spores, then sprinkle them onto a sterile growing medium. This method leverages the sporangium’s natural release mechanism, increasing the likelihood of successful germination.

In contrast to other spore-producing plants, such as mosses or liverworts, the leptosporangiate fern’s sporangium combines simplicity with sophistication. Its structure is less complex than the multi-layered sporangia of some seed plants but far more dynamic than the static spore capsules of bryophytes. This balance allows ferns to thrive in diverse environments, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands. By understanding and respecting the sporangium’s design, we can better cultivate and conserve these ancient plants, ensuring their continued role in ecosystems worldwide.

Peracetic Acid's Efficacy in Inactivating Spores: A Comprehensive Analysis

You may want to see also

Hydrodynamic factors influencing fern spore dispersal in moist environments

In moist environments, the dispersal of leptosporangiate fern spores is significantly influenced by hydrodynamic factors, which dictate how water movement interacts with spore release and transport. Water acts as both a medium and a force, shaping the trajectory and distance of spores. For instance, in riparian zones or humid forests, raindrops striking the fern’s sporangia can dislodge spores with enough force to propel them several centimeters away. This mechanism, known as splash dispersal, relies on the kinetic energy of water droplets, which varies with droplet size and velocity. Larger raindrops, typically measuring 4–5 mm in diameter, generate greater impact force, making them more effective at dislodging spores than smaller droplets. Understanding this relationship allows ecologists to predict spore dispersal patterns in areas with specific rainfall characteristics.

The role of surface tension in water bodies, such as puddles or thin films on leaves, further complicates hydrodynamic dispersal. Fern spores, often hydrophobic due to their outer coatings, can float on water surfaces, enabling passive transport. In stagnant or slow-moving water, capillary action and surface tension may cause spores to aggregate into clusters, reducing individual dispersal distances. However, in flowing water, such as streams or rivulets, spores are carried downstream, potentially reaching new habitats kilometers away. The critical velocity of water required to mobilize spores depends on their size and density; for leptosporangiate ferns, spores typically range from 30 to 50 micrometers, requiring water velocities of at least 0.1 m/s for effective transport. This highlights the importance of water flow dynamics in expanding fern populations across fragmented landscapes.

Practical applications of hydrodynamic dispersal knowledge can inform conservation strategies for fern species in moist ecosystems. For example, restoring natural water flow patterns in degraded habitats can enhance spore dispersal, promoting species recovery. Gardeners and restoration ecologists should avoid compacting soil near ferns, as this reduces water infiltration and limits splash dispersal. Additionally, maintaining small water bodies, like ephemeral pools, can serve as dispersal conduits for spores. When cultivating ferns in humid environments, ensure that irrigation systems mimic natural rainfall patterns, using sprinklers with droplet sizes of 4–5 mm to maximize spore release. These measures, grounded in hydrodynamic principles, can optimize fern propagation and ecosystem resilience.

Comparatively, hydrodynamic dispersal in ferns contrasts with wind-driven mechanisms seen in drier environments. While wind dispersal relies on spore aerodynamics and turbulence, water-mediated dispersal is more localized but highly efficient in moist settings. This distinction underscores the adaptability of leptosporangiate ferns to diverse habitats. For instance, species in tropical rainforests exploit both rain splash and flowing water for dispersal, whereas those in temperate woodlands may rely more on wind. By studying these differences, researchers can develop habitat-specific models to predict fern distribution and response to climate change. Such insights are invaluable for preserving biodiversity in increasingly fragmented and altered ecosystems.

Do All Bacillus Species Form Spores? Unraveling the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Gravity and ballistic forces in short-distance spore dispersal

Leptosporangiate ferns, the most diverse group of ferns, have evolved ingenious mechanisms to disperse their spores over short distances, leveraging both gravity and ballistic forces. These mechanisms ensure that spores land in suitable microhabitats, increasing the chances of successful germination and survival. Understanding these processes not only highlights the sophistication of fern biology but also offers insights into plant ecology and adaptation.

Gravity plays a fundamental role in short-distance spore dispersal, particularly in species with downward-facing sporangia. As the sporangium matures, it dehydrates and contracts, creating tension in the annulus—a ring of cells that functions like a spring. When the tension reaches a critical point, the annulus snaps, propelling the sporangium outward. However, the force generated is often insufficient to carry spores far, and gravity takes over. Spores released from these sporangia fall vertically, settling in the immediate vicinity of the parent plant. This strategy is especially effective in dense forest understories, where light competition is fierce, and establishing nearby can be advantageous. For example, the maidenhair fern (*Adiantum*) relies heavily on gravity-driven dispersal, with spores often landing within a few centimeters of the parent.

Ballistic forces, on the other hand, enable ferns to disperse spores slightly farther, though still within a limited range. In species like the filmy fern (*Hymenophyllum*), the sporangium acts as a miniature catapult. As the sporangium dries, the annulus contracts asymmetrically, causing it to rupture and eject spores with enough force to travel a few millimeters to centimeters. This mechanism is particularly useful in humid environments, where spores need to escape the immediate damp surroundings to avoid clumping or fungal infection. While the distance is modest, it allows spores to reach small crevices or patches of soil that might offer better germination conditions.

To observe these mechanisms in action, one can conduct a simple experiment. Collect mature fern fronds with visible sporangia and place them on a dark surface under a magnifying glass. Over time, you’ll notice spores accumulating directly below the sporangia in gravity-driven species, while in ballistic species, spores will form a scattered pattern around the frond. This hands-on approach not only illustrates the dispersal strategies but also underscores the precision with which ferns adapt to their environments.

In practical terms, gardeners and conservationists can use this knowledge to propagate ferns more effectively. For species reliant on gravity, planting parent ferns on elevated surfaces like rocks or logs can help spores reach the ground more broadly. For ballistic species, ensuring adequate air circulation around the plants can enhance spore dispersal. By mimicking natural conditions, we can support the growth and spread of these fascinating plants in both wild and cultivated settings.

Breloom's Spore Mastery: Unlocking the Secret Move in Pokémon Battles

You may want to see also

Adaptations of indusium and annulus in spore ejection processes

The indusium and annulus are critical structures in the spore dispersal mechanism of leptosporangiate ferns, each adapted to enhance the efficiency of spore ejection. The indusium, a thin, protective covering over the sporangium, serves as a humidity-sensitive trigger. When conditions are dry, it curls away from the sporangium, exposing the annulus—a ring of thickened, dead cells with a precise, elastic structure. This exposure initiates the spore release process, showcasing an adaptation that ensures spores are dispersed only when environmental conditions favor their survival and germination.

Consider the annulus as the fern’s spring-loaded mechanism. Composed of two rows of cells with differing wall thicknesses, it acts as a miniature catapult. As the indusium opens, the annulus dehydrates unevenly, causing it to snap open with explosive force. This action propels spores at speeds up to 0.1 meters per second, a remarkable feat for such a small structure. For comparison, this velocity is akin to a human sneezing, but on a microscopic scale, it’s a powerful adaptation for maximizing dispersal distance.

To visualize this process, imagine a series of steps: first, the indusium senses dry air and retracts, akin to a curtain being drawn. Next, the annulus, under tension from differential dehydration, releases its stored energy, launching spores into the air. Finally, the spores are carried away by wind currents, aided by their lightweight, dust-like structure. Practical observation tip: use a magnifying glass to watch this process in real-time on a dry, sunny day when ferns are most active in spore release.

While the indusium and annulus work in tandem, their adaptations are not without limitations. High humidity can prevent the indusium from opening, delaying spore release. Similarly, extreme dryness may cause the annulus to malfunction, reducing ejection force. For optimal observation, monitor ferns in environments with moderate humidity (40-60%) and temperatures between 20-25°C, conditions that mimic their natural habitat and trigger efficient spore dispersal.

In conclusion, the indusium and annulus are marvels of evolutionary engineering, finely tuned to optimize spore ejection in leptosporangiate ferns. Their interplay of humidity sensitivity and elastic energy storage ensures that spores are released under ideal conditions, maximizing the chances of successful colonization. By understanding these adaptations, we gain insight into the intricate strategies plants employ to thrive in diverse ecosystems.

Mosses' Aerial Spores: Unveiling the Secrets of Wind-Driven Dispersal

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The primary method of spore dispersal in leptosporangiate ferns is through the explosive release of spores from the sporangia, which are located on the undersides of the fern fronds. This mechanism is driven by the buildup and release of hygroscopic cells called annulus cells, which respond to changes in humidity.

Annulus cells are specialized, hygroscopic cells that encircle the sporangium in leptosporangiate ferns. When dry, these cells contract, causing the sporangium to open and release spores explosively. When humid, the annulus cells expand, closing the sporangium. This mechanism ensures efficient spore dispersal in response to environmental conditions.

Yes, in addition to the explosive mechanism, wind plays a significant role in dispersing spores over long distances. The lightweight, dust-like spores are easily carried by air currents. Additionally, the elevated position of the sporangia on the fronds maximizes exposure to wind, enhancing dispersal efficiency.

While wind is the primary agent of spore dispersal in leptosporangiate ferns, other factors like water splashes in moist environments can also aid in short-distance dispersal. However, wind remains the most effective means for spreading spores over large areas, ensuring colonization of new habitats.

![Greenwood Nursery: Live Perennial Plants - Ostrich Fern + Matteuccia Struthiopteris - [Qty: 2X Pint Pots] - (Click for Other Available Plants/Quantities)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71ip9qLzKjL._AC_UL320_.jpg)