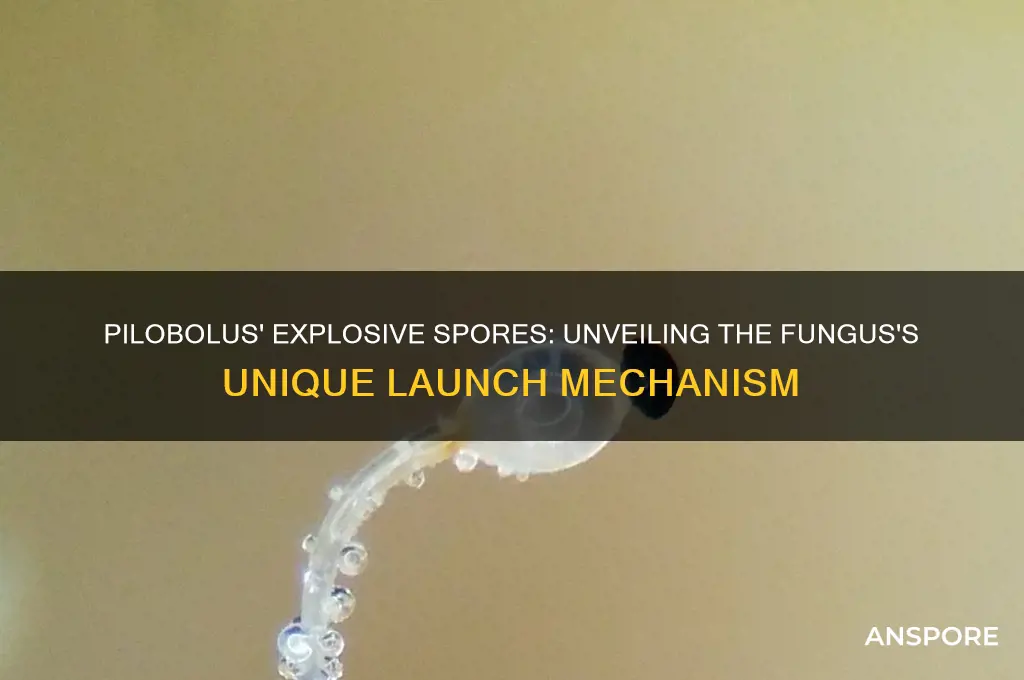

Pilobolus, a unique genus of fungi, is renowned for its remarkable ability to shoot spores with incredible force and precision. This process, known as ballistospory, involves the fungus building up pressure within a specialized structure called a sporangium, which contains the spores. When the sporangium ruptures, it acts like a spring, propelling the spores at speeds of up to 25 miles per hour over distances of several centimeters. This mechanism ensures efficient dispersal, allowing Pilobolus to colonize new habitats effectively. The fungus often grows on herbivorous animal dung, and the spore launch is strategically timed to coincide with the passage of potential hosts, maximizing the chances of spore attachment and subsequent growth in nutrient-rich environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Mechanism of Spore Launch | Uses a hydrostatic pressure mechanism to shoot spores explosively. |

| Pressure Buildup | Pressure builds up inside the spore-containing structure (sporangium). |

| Trigger Mechanism | Triggered by light, particularly blue light, detected by photoreceptors. |

| Launch Speed | Spores are ejected at speeds up to 2.5 meters per second. |

| Distance Traveled | Spores can travel up to 2 meters away from the fungus. |

| Energy Source | Energy is derived from the rapid release of stored osmotic pressure. |

| Spore Structure | Spores are encased in a gelatinous sheath that aids in adhesion. |

| Environmental Response | Optimized for dispersal in humid environments to ensure survival. |

| Biological Purpose | Ensures efficient dispersal to new habitats for colonization. |

| Scientific Significance | Studied as a model for understanding rapid biomechanical processes. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Mature sporangium pressure buildup

The mature sporangium of Pilobolus, a unique fungus, is a pressurized vessel primed for explosive spore discharge. This pressure buildup is the key to its remarkable ability to launch spores several centimeters, a feat that defies the organism's microscopic scale. But how does this pressure accumulate, and what triggers its sudden release?

Imagine a water balloon stretched to its limit, ready to burst at the slightest touch. Similarly, the Pilobolus sporangium, a spherical structure atop a slender stalk, undergoes a process of osmotic water uptake, increasing its internal pressure to levels exceeding 15 atmospheres. This pressure is not merely a byproduct but a carefully orchestrated mechanism for spore dispersal.

The Pressure-Building Process:

As the sporangium matures, it actively pumps ions across its cell membrane, creating a concentration gradient. Water follows this gradient, rushing into the sporangium through osmosis. This influx of water causes the sporangium to swell, stretching the resilient cell wall. The wall, composed of chitin and other polysaccharides, acts like a biological spring, storing potential energy as it deforms. This energy, when released, propels the spores with astonishing force.

The pressure buildup is not a gradual process but a rapid one, occurring within minutes to hours. This speed is crucial for the fungus's survival strategy, allowing it to disperse spores quickly in response to environmental cues, such as changes in light or humidity.

Triggering the Explosion:

The release of this built-up pressure is triggered by a sophisticated sensory system. Pilobolus is phototropic, meaning it grows towards light. When the sporangium is mature and pressurized, it is also light-sensitive. A sudden change in light intensity, such as a shadow passing over the fungus, can initiate the discharge. This light signal is detected by photoreceptor proteins, which activate a cascade of biochemical reactions. These reactions lead to the rapid breakdown of the cell wall at a specific point, creating a weak spot. The immense internal pressure then ruptures this weak spot, propelling the spores out of the sporangium at speeds up to 25 miles per hour.

Practical Implications:

Understanding this pressure-based spore discharge mechanism has practical applications. For instance, studying the Pilobolus sporangium's cell wall structure and its ability to withstand extreme pressure could inspire the design of new materials for engineering and medicine. Additionally, the fungus's sensitivity to light and its rapid response mechanism could provide insights into developing advanced sensors and actuators.

In the world of microbiology, Pilobolus stands out as a master engineer, harnessing the power of pressure to achieve remarkable feats. Its mature sporangium, a tiny but mighty pressure vessel, showcases the elegance and efficiency of nature's solutions, offering valuable lessons for both scientific inquiry and technological innovation.

Breathing C. Diff Spores: Risks, Prevention, and Air Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Phototropic sensor targeting light

The Pilobolus fungus, a master of precision in the natural world, employs a phototropic sensor to target light with remarkable accuracy. This sensor, akin to a biological compass, guides the fungus in aligning its spore-shooting structure toward the brightest light source, typically the sun. The mechanism hinges on photoreceptor proteins that detect light intensity and direction, triggering a series of cellular responses. These responses culminate in the differential growth of the sporangium, the structure housing the spores, causing it to bend toward the light. This phototropic targeting ensures that spores are launched into open spaces, maximizing dispersal and survival.

To replicate this mechanism in a controlled setting, consider the following steps. First, cultivate Pilobolus on a nutrient-rich substrate like cow dung, maintaining a temperature of 22–28°C for optimal growth. Introduce a controlled light source, such as a LED lamp, positioned at a specific angle to simulate natural sunlight. Observe the sporangium’s response over 24–48 hours, noting the degree of bending and the direction of spore ejection. For enhanced precision, use a spectrometer to measure light wavelengths, as Pilobolus is most responsive to blue and red light. This experimental setup allows for the study of phototropism in real-time, offering insights into the fungus’s sensory capabilities.

From an analytical perspective, the Pilobolus phototropic sensor is a marvel of evolutionary adaptation. Unlike plants, which use auxin for phototropism, Pilobolus relies on a unique blend of photoreceptors and turgor pressure changes. The sensor’s efficiency is evident in its ability to detect light gradients as subtle as 0.1% difference in intensity. This sensitivity ensures that even in dense environments, the fungus can orient itself toward the most favorable escape route for its spores. Comparative studies with other fungi reveal that Pilobolus’s phototropic mechanism is among the fastest and most accurate in the fungal kingdom, making it a prime candidate for biomimetic research.

For practical applications, understanding Pilobolus’s phototropic sensor can inspire innovations in robotics and agriculture. Imagine a robotic arm equipped with light-sensitive sensors that mimic the fungus’s ability to target light sources with precision. Such a device could be used in crop monitoring, where it identifies and addresses areas of insufficient sunlight. In agriculture, this technology could optimize plant growth by dynamically adjusting light exposure. Additionally, the principles of Pilobolus’s sensor could inform the design of self-orienting solar panels, enhancing energy capture efficiency by up to 20%.

Finally, a persuasive argument for studying Pilobolus lies in its potential to revolutionize our understanding of sensory systems. By decoding the molecular basis of its phototropic sensor, scientists could unlock new avenues in synthetic biology and bioengineering. For instance, creating biohybrid materials that respond to light could lead to advancements in medical devices, such as light-guided drug delivery systems. Moreover, the fungus’s ability to thrive in nutrient-rich but competitive environments offers lessons in resource optimization, applicable to sustainable agriculture and biotechnology. Pilobolus is not just a curiosity of nature; it is a blueprint for innovation.

Milky Spore Effectiveness: A Proven Grub Control Solution for Lawns

You may want to see also

Cellular contraction mechanism

The Pilobolus fungus, a master of spore propulsion, achieves its remarkable feat through a sophisticated cellular contraction mechanism. This process, akin to a biological spring, involves the rapid accumulation and release of osmolytes within specialized cells, creating a pressure differential that propels spores at speeds up to 2.5 meters per second. Understanding this mechanism not only sheds light on fungal biology but also inspires biomimetic applications in microfluidics and drug delivery systems.

At the heart of this mechanism lies the sporangium, a sac-like structure filled with fluid and spores. Surrounding the sporangium is a stalk composed of three distinct cell layers: the basal, middle, and outer layers. The middle layer, rich in osmotic cells, plays a pivotal role. When triggered by environmental cues like light or heat, these cells actively transport ions and water, increasing osmotic pressure. This causes the cells to swell, generating a force that compresses the fluid within the sporangium. The sudden release of this pressure, akin to popping a balloon, ejects the spores with precision and force.

To replicate this mechanism in a controlled setting, researchers have identified key parameters. For instance, the osmotic gradient must reach a critical threshold, typically achieved within 10–15 minutes of light exposure. The optimal temperature range for this process is 25–30°C, as lower temperatures slow cellular activity, while higher temperatures denature proteins. Practical experiments often use glucose or glycerol as osmolytes, with concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 1.0 M to mimic the natural process effectively.

Comparatively, this mechanism contrasts with other biological propulsion systems, such as the explosive seed dispersal of the sandbox tree. While the sandbox tree relies on mechanical tension in its fruit walls, Pilobolus harnesses osmotic pressure, showcasing the diversity of nature’s engineering solutions. This comparison underscores the efficiency of cellular contraction, which achieves high velocity with minimal energy expenditure, making it a model for designing compact, energy-efficient propulsion systems.

In practical applications, engineers can draw from Pilobolus’s mechanism to develop microfluidic devices capable of precise fluid ejection. For example, integrating osmotic cells into microchannels could enable controlled drug delivery or lab-on-a-chip technologies. By mimicking the fungal stalk’s layered structure, researchers can create synthetic materials that respond to environmental stimuli, such as light or temperature, to release payloads on demand. This bioinspired approach not only honors nature’s ingenuity but also opens new frontiers in technology.

Mastering TSearch on Spore: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spores' aerodynamic trajectory

The pilobolus fungus launches its spores with an explosive force, reaching speeds up to 25 mph, a remarkable feat for a microscopic organism. This acceleration, achieved in less than 0.02 seconds, rivals the fastest human-made projectiles. Understanding the aerodynamic trajectory of these spores reveals a sophisticated interplay of physics and biology, optimized for dispersal and survival.

To analyze the trajectory, consider the spore’s initial velocity, angle of projection, and environmental factors like air resistance and humidity. The pilobolus spore is ejected at a nearly vertical angle, typically 80-90 degrees, maximizing height rather than distance. This strategy ensures spores ascend above the forest floor canopy, where air currents can carry them farther. However, this steep angle reduces horizontal range, a trade-off for increased exposure to wind dispersal. Air resistance, though minimal due to the spore’s small size (5-10 μm), still plays a role in deceleration, particularly during descent.

Practical observation of spore trajectory can be conducted using high-speed cameras (frame rates of 10,000 fps or higher) to capture the launch dynamics. For enthusiasts, a simple setup involves illuminating the fungus with a side-angled LED light and recording the spore ejection in a controlled humidity environment (70-80% RH). Analyzing the footage using motion-tracking software (e.g., Tracker or ImageJ) allows measurement of velocity, angle, and parabolic path. This hands-on approach not only validates theoretical models but also highlights the precision of the pilobolus’s spore-shooting mechanism.

Comparatively, the pilobolus spore’s trajectory differs from other fungal dispersal methods, such as puffball fungi, which rely on passive release or external forces like raindrop impact. The pilobolus’s active, high-velocity launch is energetically costly but ensures spores reach heights where wind currents are stronger and more consistent. This adaptation is particularly advantageous in dense, shaded environments where passive dispersal would be less effective.

In conclusion, the aerodynamic trajectory of pilobolus spores is a masterclass in biological engineering. By prioritizing vertical ascent and leveraging environmental air currents, the fungus maximizes dispersal efficiency. For researchers and hobbyists alike, studying this trajectory offers insights into biomechanics and inspires biomimetic applications, such as micro-projectile technologies or efficient seed dispersal systems.

Do Spores Have Seed Coats? Unraveling Plant Reproduction Mysteries

You may want to see also

Environmental triggers for release

The Pilobolus fungus, a master of precision and timing, relies on environmental cues to trigger its explosive spore release. Light, particularly blue light, acts as a critical signal, initiating a cascade of events within the sporangium. This phototropic response ensures spores are launched during daylight hours, maximizing their chances of landing on a suitable host, such as a plant leaf, where they can germinate and continue the fungal life cycle.

Consider the process as a finely tuned alarm system. When light reaches a specific intensity—typically around 1000 lux, equivalent to a brightly lit room—the fungus begins to orient its sporangium toward the light source. This alignment is crucial, as it positions the spore-filled structure for optimal trajectory. Within minutes of exposure, the fungus initiates a rapid increase in osmotic pressure, building up energy like a coiled spring.

Humidity plays a secondary but equally vital role. Pilobolus thrives in damp environments, and moisture levels above 80% are necessary to maintain the turgor pressure required for spore ejection. Dry conditions can halt the process entirely, as the fungus conserves energy and waits for more favorable conditions. Think of humidity as the fuel that keeps the mechanism primed—without it, the trigger remains inactive.

Temperature acts as a modulator, influencing the speed and efficiency of spore release. Optimal temperatures range between 25°C and 30°C (77°F to 86°F), mirroring the warm, humid conditions of its natural habitat. Below 20°C, the process slows significantly, while temperatures above 35°C can denature proteins essential for the mechanism. This thermal sensitivity ensures the fungus operates within a narrow ecological window, reducing energy waste and increasing survival odds.

For those studying or cultivating Pilobolus, replicating these environmental triggers is key. Use a grow light emitting blue wavelengths (450–495 nm) to simulate daylight, maintaining a consistent 1000 lux intensity. Pair this with a humidifier to keep moisture levels above 80%, and monitor temperature with a thermostat set to 28°C for peak performance. Observing these conditions not only demonstrates the fungus’s remarkable adaptation but also highlights the intricate interplay between organisms and their environment.

Are Spore-Printed Mushroom Caps Safe to Eat? A Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Pilobolus uses a unique mechanism called a "spore cannon" to shoot its spores. It builds up pressure inside a swollen structure called a sporangium, which then bursts, propelling the spores at high speeds.

The Pilobolus is triggered to shoot its spores by environmental factors such as light, particularly sunlight. Light stimulates the maturation and bursting of the sporangium, releasing the spores.

Pilobolus spores can travel up to 2 meters (6.5 feet) when shot, thanks to the high pressure and speed generated by the sporangium's burst.

The purpose of shooting spores is to disperse them away from the parent fungus, increasing the chances of reaching new habitats and colonizing fresh dung (its primary substrate).

Pilobolus spores can reach speeds of up to 25 meters per second (56 mph) when shot, making it one of the fastest acceleration rates in the biological world.