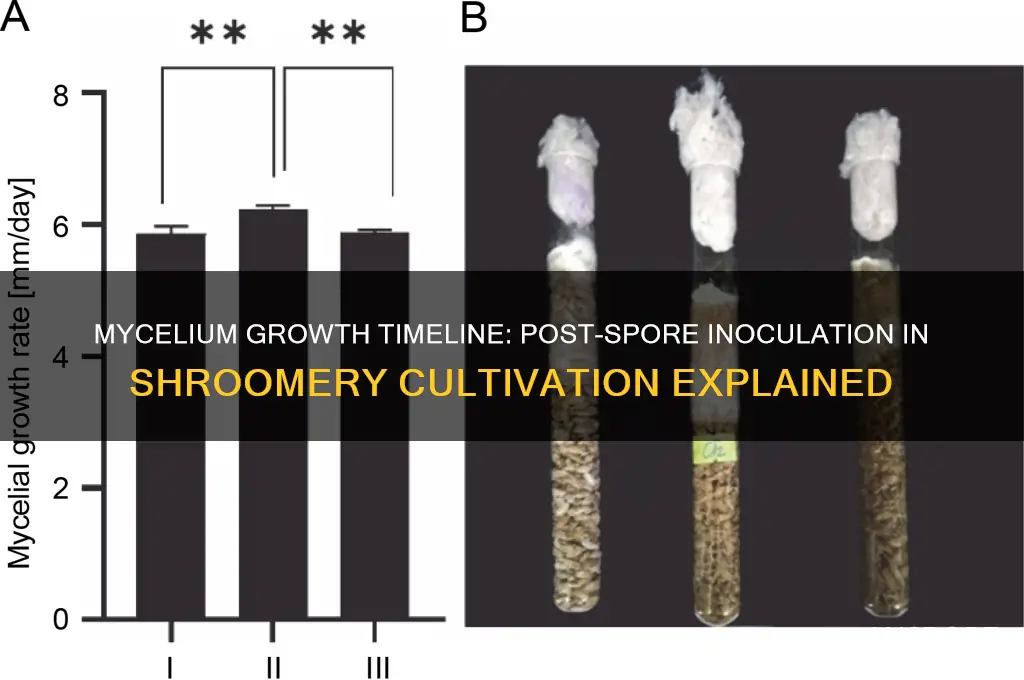

Mycelium growth after spore inoculation in a shroomery typically begins within 7 to 14 days, depending on factors such as temperature, humidity, substrate quality, and spore viability. During this initial phase, spores germinate and develop into hyphae, which then colonize the substrate, forming a dense network of mycelium. Optimal conditions, such as a temperature range of 70–75°F (21–24°C) and high humidity, accelerate this process. However, contamination risks are highest during this stage, so sterile techniques and proper environmental control are crucial. Once established, the mycelium continues to expand until the substrate is fully colonized, which can take 2 to 6 weeks, setting the stage for fruiting body (mushroom) development.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Time for Mycelium Growth | Typically 7-14 days, but can range from 5 days to several weeks |

| Factors Affecting Growth Time | Substrate type, temperature, humidity, spore viability, and technique |

| Optimal Temperature Range | 70-75°F (21-24°C) |

| Humidity Requirement | High humidity (above 90%) |

| Substrate Preparation | Sterilized or pasteurized, properly hydrated |

| Spore Viability | Fresh spores germinate faster; older spores may take longer |

| Contamination Risk | Higher in unsterile conditions; proper sterilization reduces risk |

| Signs of Mycelium Growth | White, cobweb-like growth spreading across the substrate |

| Common Techniques | Agar work, grain spawn, direct inoculation of bulk substrate |

| Species Variation | Some mushroom species grow faster than others (e.g., oyster mushrooms) |

| Light Requirement | Minimal; indirect light is sufficient |

| pH Level | Slightly acidic to neutral (pH 5.5-7.0) |

| Air Exchange | Minimal during colonization; avoid excessive airflow |

| Post-Colonization Steps | Transfer to fruiting chamber for mushroom development |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Optimal temperature range for mycelium growth post-inoculation

- Humidity levels required for successful mycelium colonization

- Substrate preparation techniques to accelerate mycelium development

- Sterilization methods to prevent contamination during inoculation

- Timeframe variations based on mushroom species and conditions

Optimal temperature range for mycelium growth post-inoculation

Mycelium growth post-inoculation is highly sensitive to temperature, with the optimal range typically falling between 70°F and 75°F (21°C to 24°C). Within this window, mycelium colonizes substrate most efficiently, balancing metabolic activity and resource utilization. Temperatures below 65°F (18°C) slow growth significantly, while those above 80°F (27°C) risk stressing the mycelium, potentially halting colonization or promoting contamination. For cultivators, maintaining this narrow range is critical, often requiring thermostats, heating pads, or air conditioning to stabilize environmental conditions.

Analyzing the science behind this range reveals why it’s so precise. Mycelium is a fungus, and like all fungi, its enzymatic processes are temperature-dependent. At 70°F to 75°F, enzymes function optimally, breaking down substrate nutrients and facilitating rapid growth. Below this range, enzymatic activity slows, extending colonization time. Above it, enzymes denature, disrupting metabolic pathways and leaving the mycelium vulnerable to competitors like bacteria. For instance, a 5°F deviation can double colonization time, while a 10°F increase may halt growth entirely.

Practical tips for achieving this range include using a digital thermometer to monitor substrate temperature, not just ambient air. For small-scale growers, a seedling heat mat set to low can maintain warmth in cooler environments, while a small fan or air circulation system prevents overheating in warmer climates. For larger operations, insulated grow rooms with temperature controllers are ideal. Avoid placing inoculated substrates near windows, vents, or doors, where temperatures fluctuate. Instead, opt for centralized, stable locations within the growing area.

Comparing temperature management strategies highlights the trade-offs. Passive methods, like choosing a naturally temperate room, are cost-effective but less reliable. Active methods, such as heating pads or air conditioners, offer precision but increase energy costs. A middle ground is using insulated containers or blankets to buffer temperature swings, paired with occasional manual adjustments. For example, a grower in a temperate climate might use a heat mat during cooler nights and rely on ambient conditions during warmer days, striking a balance between efficiency and expense.

In conclusion, mastering the optimal temperature range for mycelium growth post-inoculation is a blend of science and practicality. By understanding the enzymatic processes at play and implementing targeted strategies, cultivators can minimize colonization time and maximize success. Whether through high-tech controllers or low-cost adaptations, maintaining 70°F to 75°F is non-negotiable for healthy, vigorous mycelium development.

Neisseria Spore Formation: Unraveling the Truth Behind This Bacterial Mystery

You may want to see also

Humidity levels required for successful mycelium colonization

Maintaining optimal humidity is critical during the mycelium colonization phase, as it directly influences the speed and success of fungal growth after spore inoculation. Mycelium thrives in environments with high moisture content, typically requiring humidity levels between 95% and 100%. At these levels, water vapor in the air supports the absorption and transport of nutrients, enabling the mycelium to expand efficiently. Lower humidity can lead to dehydration, stunted growth, or even colonization failure, while inconsistent moisture levels may introduce contaminants. Therefore, precise humidity control is non-negotiable for cultivators aiming to accelerate and ensure successful colonization.

Achieving and sustaining these humidity levels often involves practical techniques tailored to the cultivation setup. For instance, using a humidifier in the incubation chamber or tent can help maintain the required moisture. Alternatively, placing a tray of water or damp sphagnum moss inside the container creates a natural humid microclimate. For small-scale projects, sealing the substrate in a plastic bag or container with a damp paper towel can suffice. Monitoring humidity with a hygrometer is essential, as fluctuations below 90% can halt mycelium growth. Regularly misting the interior or adjusting ventilation ensures the environment remains saturated without promoting mold or bacterial growth.

Comparing humidity requirements across different stages of cultivation highlights its unique importance during colonization. While fruiting bodies (mushrooms) require lower humidity (85-95%) and increased airflow, mycelium demands near-constant saturation to establish itself. This distinction underscores why cultivators often use separate chambers for colonization and fruiting. During colonization, the focus is on creating a sterile, humid environment conducive to mycelial expansion, whereas fruiting prioritizes gas exchange and light exposure. Understanding this difference prevents common mistakes, such as introducing airflow too early, which can dry out the substrate and impede colonization.

Finally, troubleshooting humidity-related issues is key to salvaging a colonization attempt. If mycelium growth appears slow or patchy, check for dry spots in the substrate, which indicate inadequate humidity. Rehydrating the substrate by misting or gently soaking it can revive stalled growth. Conversely, condensation on container walls or a soggy substrate suggests excessive moisture, which risks contamination. In such cases, improving ventilation or reducing water sources can restore balance. Patience is crucial, as mycelium colonization can take 2-4 weeks under optimal conditions, but humidity mismanagement can extend this timeline or lead to failure. Consistent vigilance ensures the mycelium receives the moisture it needs to flourish.

Effective Ways to Eliminate Mold Spores and Keep Your Home Healthy

You may want to see also

Substrate preparation techniques to accelerate mycelium development

The speed of mycelium colonization after spore inoculation hinges significantly on substrate preparation. A well-prepared substrate provides the ideal environment for mycelium to thrive, reducing the time from inoculation to full colonization. One critical factor is sterilization. Autoclaving your substrate at 15 psi for 60–90 minutes ensures all competing microorganisms are eliminated, giving your mycelium a head start. Inadequate sterilization often leads to contamination, delaying or even halting growth entirely.

Beyond sterilization, moisture content plays a pivotal role. Mycelium requires a substrate with 60–70% moisture to grow efficiently. Too dry, and the mycelium struggles to spread; too wet, and anaerobic conditions can suffocate it. To achieve this balance, squeeze a handful of the substrate—it should feel like a wrung-out sponge. If water drips, it’s too wet; if it crumbles, it’s too dry. Adjust by adding water or allowing excess moisture to evaporate before inoculation.

Nutrient composition is another accelerator. Mycelium thrives on a substrate rich in cellulose and lignin, commonly found in materials like straw, wood chips, or manure. Supplementing with bran or gypsum can further enhance growth. For example, a 50/50 mix of pasteurized straw and vermiculite, amended with 10% gypsum by weight, provides a balanced nutrient profile. Avoid over-amending, as excessive nutrients can lead to contamination or overly dense mycelium that struggles to fruit.

Finally, particle size matters. Finely ground substrates increase the surface area available for mycelium colonization, accelerating growth. However, overly fine particles can compact, reducing air exchange. Aim for a substrate with particles between 1–2 cm in size. This ensures optimal oxygenation while maximizing contact points for mycelium to spread. By combining these techniques—sterilization, moisture control, nutrient balance, and particle size optimization—you can significantly reduce the time from spore inoculation to full mycelium colonization, often cutting weeks off the process.

Haploid or Diploid: Unraveling the Mystery of Plant Spores

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Sterilization methods to prevent contamination during inoculation

Contamination is the arch-nemesis of successful mycelium growth, and inoculation is its prime opportunity to strike. Even a single stray bacterium or mold spore can derail weeks of careful cultivation. Sterilization, therefore, isn't just a step—it's the foundation of your shroomery's success.

Pressure cooking: The gold standard. Autoclaving, or pressure cooking, is the most reliable method for sterilizing substrates and tools. It uses steam under pressure (15-20 PSI) to reach temperatures of 121°C (250°F), effectively killing all microorganisms, including spores. For grain substrates, cook for 60-90 minutes; denser materials like manure-based substrates may require up to 2 hours. Always allow the cooker to cool naturally to avoid boiling over or compromising sterility.

Chemical sterilization: A double-edged sword. Isopropyl alcohol (90%+ concentration) is a quick fix for sterilizing small tools like scalpels or syringes. Flame sterilization, where metal tools are passed through an open flame, is equally effective but requires precision to avoid damage. However, chemicals like hydrogen peroxide or bleach are unsuitable for substrates—they leave residues harmful to mycelium. Reserve these methods for surfaces and equipment, not your growing medium.

Tyndallization: A gentler alternative. For heat-sensitive substrates, tyndallization offers a workaround. This process involves boiling the substrate for 1 hour on three consecutive days, allowing it to cool between sessions. While not as foolproof as autoclaving, it’s sufficient for less demanding species or hobbyist setups. Note: this method is time-consuming and carries a higher risk of contamination if not executed meticulously.

Environmental control: The unsung hero. Sterilization doesn’t end with your substrate. Work in a clean, clutter-free space, and use a still-air box or laminar flow hood to minimize airborne contaminants during inoculation. Wear gloves, a mask, and a lab coat to reduce human-borne contaminants. Even the smallest oversight—a sneeze, a dirty countertop—can introduce competitors to your mycelium’s ecosystem.

Mastering sterilization is less about following a recipe and more about adopting a mindset. Think like a surgeon: meticulous, deliberate, and aware of every potential breach. With consistent practice, these methods become second nature, paving the way for robust mycelium growth and bountiful harvests.

Can Spores Survive Stomach Acid? Unraveling the Digestive Mystery

You may want to see also

Timeframe variations based on mushroom species and conditions

The time it takes for mycelium to colonize after spore inoculation varies dramatically depending on the mushroom species and environmental conditions. For instance, *Oyster mushrooms* (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) are known for their rapid colonization, often showing visible mycelium growth within 7–14 days under optimal conditions. In contrast, *Lion’s Mane* (*Hericium erinaceus*) can take 3–4 weeks to fully colonize, while *Reishi* (*Ganoderma lucidum*) may require 6–8 weeks due to its slower metabolic rate. These differences highlight the importance of species-specific expectations when cultivating mushrooms.

Environmental conditions play a pivotal role in accelerating or delaying mycelium growth. Temperature is a critical factor: most mushroom species thrive in a range of 70–75°F (21–24°C), but deviations can slow or halt growth. For example, *Shiitake* (*Lentinula edodes*) mycelium grows optimally at 75–80°F (24–27°C), while *Maitake* (*Grifola frondosa*) prefers slightly cooler temperatures around 68–72°F (20–22°C). Humidity levels must also be carefully managed; too dry, and the mycelium will struggle to spread; too damp, and contamination risks increase. Proper ventilation is equally essential to prevent CO₂ buildup, which can stunt growth.

Substrate composition and preparation further influence colonization timeframes. *Button mushrooms* (*Agaricus bisporus*) grow efficiently on composted manure, typically colonizing within 14–21 days, while *Chaga* (*Inonotus obliquus*) requires hardwood substrates and can take 6–12 months to fully colonize. Sterilizing substrates is crucial for species sensitive to contamination, such as *Psilocybe cubensis*, which can colonize in 7–14 days if conditions are sterile. For wood-loving species, pasteurization rather than sterilization may be sufficient, but this can extend colonization times.

Practical tips can help optimize mycelium growth across species. For faster-colonizing mushrooms like *Oyster* or *Enoki*, using a grain spawn can reduce colonization time by providing a nutrient-rich base. Maintaining a consistent environment with a grow tent or incubator can mitigate fluctuations in temperature and humidity. For slower species like *Reishi* or *Chaga*, patience is key—rushing the process can lead to contamination or failure. Regularly monitoring pH levels (ideal range: 5.5–6.5 for most species) and adjusting as needed can also support healthy mycelium development.

Understanding these variations allows cultivators to tailor their approach to specific mushroom species and conditions. While some species reward quick results, others demand long-term commitment. By controlling temperature, humidity, substrate quality, and environmental stability, growers can minimize delays and maximize success. Whether cultivating for food, medicine, or study, recognizing these timeframe differences is essential for achieving consistent and productive mycelium growth.

Do Spores Contain Nutrients? Unlocking Their Nutritional Potential

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mycelium growth usually begins to appear within 7 to 21 days after spore inoculation, depending on factors like temperature, humidity, and substrate quality.

Maintain a temperature range of 75–80°F (24–27°C), keep humidity levels around 95%, and ensure proper sterilization of the substrate to promote quicker mycelium colonization.

Yes, it’s normal for mycelium growth to take up to 3–4 weeks, especially in cooler conditions or with slower-colonizing mushroom species. Patience is key during this stage.

Check for contamination, ensure proper environmental conditions, and verify that the substrate was adequately sterilized. If issues persist, consider re-inoculating with a fresh spore syringe.