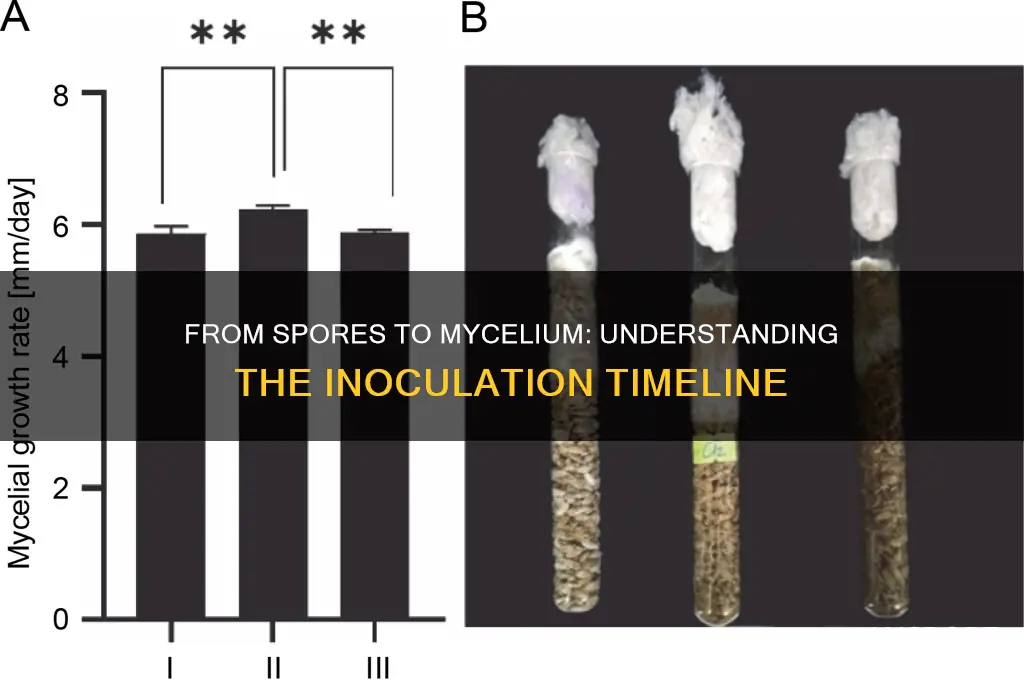

The time from inoculation of spores to the development of mycelium varies depending on factors such as the mushroom species, environmental conditions, and cultivation techniques. Generally, after spores are inoculated into a suitable substrate, germination can begin within 24 to 48 hours under optimal conditions. However, the visible formation of mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus, typically takes longer, ranging from 7 to 14 days. During this period, the spores germinate, and the resulting hyphae grow and colonize the substrate, forming a dense network of mycelium. Temperature, humidity, and substrate composition play critical roles in determining the speed of this process, with warmer temperatures and higher humidity often accelerating growth. Patience and precise control of environmental factors are essential for successful mycelium development.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Time to Germination | 2-7 days (varies by species and conditions) |

| Optimal Temperature Range | 22-28°C (72-82°F) for most species |

| Humidity Requirement | High humidity (85-95%) is critical for successful germination |

| Substrate Moisture | Substrate should be moist but not waterlogged |

| Light Requirements | Minimal light needed; darkness is often preferred |

| Species Variability | Time can differ significantly (e.g., Pleurotus ostreatus vs. Ganoderma lucidum) |

| Inoculation Density | Higher spore density can accelerate mycelium growth |

| Substrate Type | Nutrient-rich substrates (e.g., sawdust, straw) enhance growth speed |

| pH Level | Optimal pH range is 5.5-6.5 for most species |

| Contamination Risk | High during early stages; sterile conditions are crucial |

| Mycelium Visibility | Visible mycelium typically appears 7-14 days post-inoculation |

| Environmental Factors | Airflow, cleanliness, and absence of competitors impact timing |

| Commercial vs. Home Cultivation | Commercial setups may achieve faster results due to optimized conditions |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Optimal temperature range for spore germination and mycelium growth

- Humidity levels required for successful spore-to-mycelium transition

- Substrate preparation techniques to accelerate mycelium development

- Impact of light exposure on spore inoculation and growth

- Common contaminants delaying mycelium formation post-inoculation

Optimal temperature range for spore germination and mycelium growth

Temperature is the linchpin for transforming dormant spores into thriving mycelium. The optimal range for spore germination typically falls between 22°C and 28°C (72°F–82°F), with 25°C (77°F) often cited as the sweet spot. At this temperature, spores absorb water, activate metabolic processes, and initiate hyphal growth within 24 to 48 hours post-inoculation. Deviating below 20°C (68°F) slows germination, while exceeding 30°C (86°F) risks desiccating the spores or denaturing enzymes critical for viability.

Once germination begins, mycelium growth thrives in a slightly cooler range of 20°C to 26°C (68°F–79°F). This phase demands consistency; fluctuations outside this range can stall growth or promote contamination. For instance, temperatures above 28°C (82°F) may accelerate metabolism but also increase the risk of bacterial or mold competitors outpacing the mycelium. Conversely, temperatures below 18°C (64°F) slow growth to a near halt, prolonging the time to visible mycelium colonization by 5 to 7 days.

Practical tips for maintaining optimal temperatures include using heating mats or thermostatically controlled incubators for precision. For low-tech setups, placing inoculated substrates near a stable heat source (e.g., a warm basement or insulated grow tent) can suffice. Monitoring with a digital thermometer ensures the range stays within 1°C of the target, especially during critical germination hours.

Comparatively, species like *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushrooms) tolerate a broader range of 18°C to 30°C (64°F–86°F), while *Ganoderma lucidum* (reishi) prefers a narrower window of 24°C to 28°C (75°F–82°F). Understanding species-specific requirements is crucial, as even slight deviations can double or halve the time from inoculation to visible mycelium.

In conclusion, temperature control is not just about speed but also about ensuring robust, contamination-free growth. By adhering to the optimal ranges for germination and mycelium development, cultivators can reliably achieve colonization within 7 to 14 days, setting the stage for a successful fruiting cycle.

Injecting Spores into Substrate: A Comprehensive Guide for Mushroom Growers

You may want to see also

Humidity levels required for successful spore-to-mycelium transition

The germination of spores into mycelium is a delicate process heavily influenced by environmental conditions, with humidity playing a pivotal role. Spores, being the dormant, resilient form of fungi, require specific triggers to awaken and initiate growth. Among these, moisture is critical because it activates the metabolic processes necessary for germination. Without adequate humidity, spores remain inert, unable to absorb water or nutrients, stalling the transition to mycelium. Conversely, excessive moisture can lead to anaerobic conditions or contamination, equally detrimental to success.

To achieve a successful spore-to-mycelium transition, maintaining humidity levels between 70% and 90% is essential. This range ensures spores can hydrate and begin metabolic activity while preventing waterlogging or mold growth. For practical application, use a hygrometer to monitor humidity and a humidifier or misting system to adjust levels. In low-humidity environments, placing a tray of water near the growing substrate or using a humidity-retaining material like perlite can help stabilize moisture. Conversely, in high-humidity settings, ensure proper ventilation to avoid stagnation.

A comparative analysis of humidity’s role reveals its dual nature as both catalyst and potential hazard. While sufficient moisture is indispensable for spore activation, it must be balanced with other factors like temperature and airflow. For instance, at 75% humidity and 24–28°C (75–82°F), spores typically germinate within 3–7 days, forming visible mycelium. However, at 95% humidity, the risk of contamination skyrockets, often leading to failure. This underscores the importance of precision in humidity control, particularly during the critical first week of inoculation.

Persuasively, investing in a humidity-controlled environment is non-negotiable for anyone serious about cultivating mycelium from spores. DIY solutions, such as using a clear plastic dome or tent to create a microclimate, can be effective but require vigilant monitoring. Commercial growers often employ automated systems to maintain optimal conditions, ensuring consistency and reducing the risk of human error. For hobbyists, a simple yet effective strategy is to mist the substrate lightly twice daily, ensuring the surface remains damp but not saturated.

In conclusion, mastering humidity levels is the linchpin of successful spore-to-mycelium transition. By maintaining 70–90% humidity, monitoring environmental conditions, and employing practical techniques, cultivators can significantly enhance germination rates and mycelium development. Whether through low-cost DIY methods or advanced automation, the key lies in consistency and attention to detail, transforming the art of fungal cultivation into a science.

Understanding Mold Reproduction: The Role of Spores Explained

You may want to see also

Substrate preparation techniques to accelerate mycelium development

The time from spore inoculation to visible mycelium growth can vary significantly, typically ranging from 7 to 21 days, depending on factors like substrate quality, environmental conditions, and spore viability. To expedite this process, substrate preparation emerges as a critical lever. Properly prepared substrates provide the ideal nutrient profile, moisture balance, and structure for spores to germinate and mycelium to thrive. Here’s how to optimize substrate preparation to accelerate mycelium development.

Sterilization and hydration are non-negotiable steps in substrate preparation. Autoclaving substrates at 121°C (250°F) for 60–90 minutes ensures elimination of competing microorganisms while preserving nutrient integrity. For smaller batches, pressure cooking works equally well. After sterilization, allow the substrate to cool to 25–30°C (77–86°F) before inoculation. Hydration is equally critical; aim for a moisture content of 60–70% to provide adequate water without waterlogging. Use a squeeze test: a handful of substrate should release 2–3 drops of water when squeezed firmly. Overhydration can suffocate spores, while underhydration slows germination.

Nutrient enrichment can dramatically shorten colonization time. Supplementing substrates with simple carbohydrates like molasses (1–2% by weight) or complex additives like wheat bran (10–20%) provides readily available energy sources for mycelium growth. For example, a 5-liter substrate batch benefits from 50–100 grams of wheat bran or 50–100 milliliters of molasses dissolved in water. Avoid over-supplementation, as excessive nutrients can lead to contamination or unbalanced growth. Additionally, incorporating gypsum (1–2% by weight) improves substrate structure and calcium availability, further supporting mycelium development.

Physical structure and particle size play subtle but significant roles. Fine-textured substrates (2–5 mm particle size) offer more surface area for mycelium attachment but can compact easily, reducing oxygen availability. Coarser substrates (5–10 mm) promote aeration but may slow initial colonization. A balanced approach—blending 70% fine material with 30% coarse—optimizes both factors. Loosely packing the substrate into grow bags or trays ensures adequate airflow while maintaining structural integrity.

Pre-inoculation treatments can give spores a head start. Soaking substrates in a nutrient-rich solution (e.g., 1% sugar water) for 24 hours before sterilization can pre-activate metabolic pathways, reducing lag time. Alternatively, a brief cold shock (4°C for 12–24 hours) post-sterilization can synchronize spore germination, leading to more uniform mycelium growth. These techniques require precision but can shave 2–3 days off colonization time when executed correctly.

By combining meticulous sterilization, strategic nutrient supplementation, thoughtful substrate structuring, and innovative pre-treatments, growers can significantly accelerate the transition from spores to mycelium. While each technique contributes individually, their synergistic application yields the most dramatic results, turning weeks into days and maximizing efficiency in mycelium cultivation.

Exploring Tribal Planet Spore: Capturing Its Essence in Your Gameplay

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact of light exposure on spore inoculation and growth

Light exposure significantly influences the timeline from spore inoculation to mycelium development, acting as both a catalyst and inhibitor depending on its intensity and duration. Spores of many fungi, such as * Psilocybe * and * Ganoderma *, require specific light conditions to trigger germination. For instance, red light (660 nm) has been shown to accelerate spore germination in * Pleurotus ostreatus * by up to 40% compared to darkness, likely due to its role in activating photoreceptors like phytochrome. Conversely, prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light can damage spore DNA, delaying or halting germination altogether. Practical tip: Use a red LED grow light with a wavelength of 660 nm for 12 hours daily to optimize germination rates in controlled environments.

The impact of light extends beyond germination, affecting mycelium growth and morphology. Low-intensity blue light (450 nm) promotes denser, more compact mycelial mats in species like * Trichoderma *, while high-intensity white light can lead to elongated, spindly growth. This phenomenon is attributed to light-induced changes in gene expression, particularly those related to hyphal branching and cell wall synthesis. Caution: Avoid exposing spores to direct sunlight, as the combined intensity of visible and UV light can inhibit growth or cause photobleaching of pigments essential for fungal metabolism.

In practical applications, such as mushroom cultivation, light exposure must be carefully managed to align with the desired growth timeline. For example, * Agaricus bisporus * spores inoculated under diffused fluorescent light (20–50 μmol/m²/s) typically develop visible mycelium within 7–10 days, whereas those kept in complete darkness may take up to 14 days. To expedite this process, introduce light gradually, starting with 4 hours daily and increasing to 8–12 hours as mycelium becomes established. For species sensitive to light, like * Cordyceps *, maintain darkness during the initial 5–7 days post-inoculation to ensure successful colonization.

Comparatively, light’s role in spore inoculation and mycelium growth differs from its effects on fruiting bodies, where it often triggers primordia formation. This duality underscores the importance of stage-specific light management. For instance, while * Lion’s Mane * (* Hericium erinaceus *) spores benefit from low-intensity light during mycelium growth, fruiting requires higher light levels (100–200 lux) to stimulate mushroom development. Takeaway: Tailor light exposure to the growth stage—dim, controlled light for inoculation and early mycelium, and brighter light for fruiting—to optimize the entire cultivation cycle.

Finally, environmental factors like temperature and humidity interact with light exposure to shape growth outcomes. Optimal conditions for light-dependent germination typically include temperatures of 22–26°C and humidity levels above 70%. For example, * Shiitake * (* Lentinula edodes *) spores exposed to 10–12 hours of green light (520 nm) daily under these conditions can produce mycelium within 5–7 days, compared to 10–12 days in suboptimal setups. Practical tip: Use a hygrometer and thermometer to monitor conditions, and pair light exposure with proper ventilation to prevent mold contamination while fostering healthy mycelium development.

Bacterial Survival Strategies: Understanding Spore Syringe Resilience and Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Common contaminants delaying mycelium formation post-inoculation

The journey from spore inoculation to mycelium formation is a delicate process, often hindered by contaminants that thrive in the same nutrient-rich environments. Understanding these common invaders is crucial for anyone cultivating fungi, as they can significantly delay or even halt mycelium development. Here, we delve into the culprits and their impact.

Bacterial Contaminants: A Stealthy Threat

Bacteria, particularly *Bacillus* and *Pseudomonas* species, are among the most pervasive contaminants in fungal cultures. These microorganisms outcompete spores for nutrients, producing inhibitory compounds that stunt mycelium growth. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* can form biofilms that physically block spore germination. To mitigate this, sterilize substrates thoroughly using autoclaving at 121°C for 20–30 minutes. Additionally, incorporating 0.1% hydrogen peroxide into the agar medium can suppress bacterial growth without harming spores. Regularly inspect cultures under a microscope to detect early bacterial colonization, as timely intervention is key.

Mold: The Visible Adversary

Molds, such as *Trichoderma* and *Aspergillus*, are fast-growing fungi that quickly dominate cultures, depleting resources and releasing mycotoxins that inhibit mycelium formation. *Trichoderma* species are particularly notorious for their ability to parasitize other fungi. Prevent mold contamination by using HEPA filters in grow rooms to reduce airborne spores and maintaining relative humidity below 60%. If mold appears, isolate the contaminated area immediately and treat with a 10% bleach solution to prevent spread. For long-term prevention, consider adding a small amount of cinnamon or clove oil to substrates, as their antifungal properties can deter mold growth.

Yeast: The Silent Competitor

Yeast contamination often goes unnoticed until it’s too late. Species like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* consume sugars rapidly, leaving spores starved for essential nutrients. Yeast colonies appear as creamy, glossy patches on agar plates or substrates. To combat yeast, reduce the sugar content in your substrate by 20% and maintain a pH below 5.5, as yeast thrives in neutral to alkaline conditions. For existing cultures, a 1% acetic acid solution can be applied to inhibit yeast growth without harming mycelium. Always use sterile tools and gloves when handling cultures to avoid introducing yeast from skin or equipment.

Practical Takeaways for Faster Mycelium Formation

To minimize contaminants, adopt a multi-pronged approach. First, ensure all equipment and substrates are sterilized using proven methods like autoclaving or pressure cooking. Second, maintain a clean workspace with proper airflow and humidity control. Third, monitor cultures daily for early signs of contamination, such as discoloration or unusual textures. Finally, consider using antifungal agents sparingly and strategically, as overuse can harm mycelium. By addressing these common contaminants, cultivators can significantly reduce delays in mycelium formation, ensuring a healthier and more productive fungal culture.

Peracetic Acid's Efficacy in Inactivating Spores: A Comprehensive Analysis

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

It usually takes 7 to 14 days for spores to germinate and visible mycelium to form, depending on the mushroom species and environmental conditions.

Factors include temperature, humidity, substrate quality, spore viability, and the specific mushroom species being cultivated.

Yes, maintaining optimal conditions such as a temperature range of 75–80°F (24–27°C), high humidity, and sterile techniques can speed up the process.

Yes, variability is common due to differences in spore viability, genetic diversity, and environmental inconsistencies.

Check for contamination, ensure proper environmental conditions, and verify spore viability. If issues persist, consider re-inoculating with fresh spores.