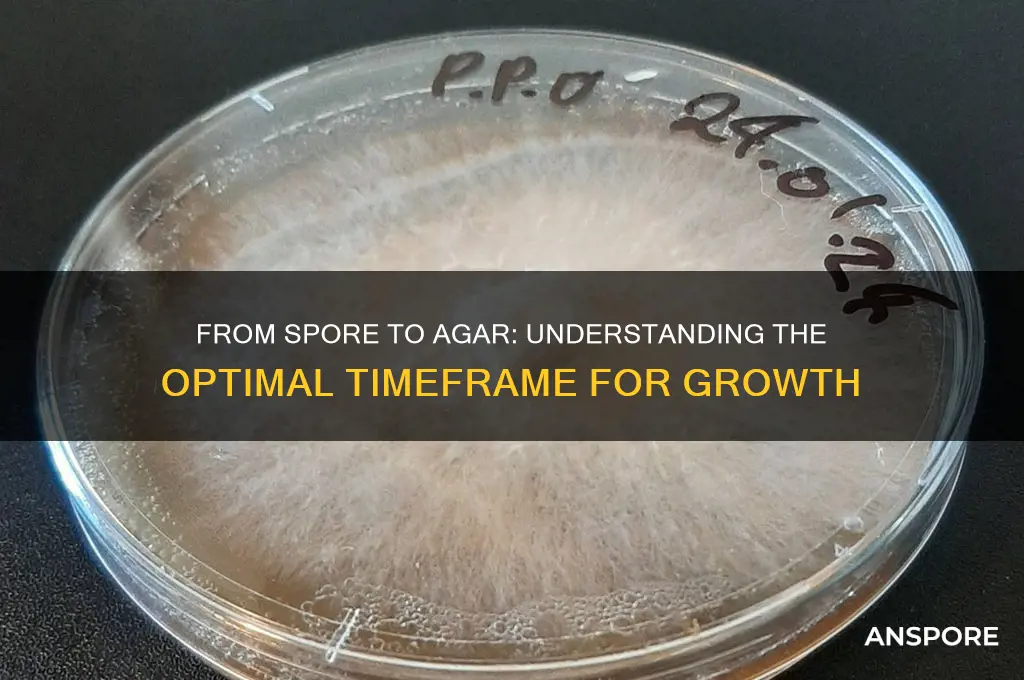

The process of growing mushrooms from spores to agar is a fascinating journey that requires patience, precision, and a deep understanding of mycology. It begins with the inoculation of spores onto a sterile agar medium, where they germinate and develop into mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus. The time it takes for this transformation varies depending on the mushroom species, environmental conditions, and the quality of the agar and spores. Generally, it can take anywhere from 7 to 21 days for visible mycelial growth to appear on the agar, though some species may take longer. This initial stage is crucial, as it lays the foundation for successful colonization and eventual fruiting, making it essential for cultivators to monitor conditions closely to ensure optimal growth.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Time for Spore Germination | Typically 12-24 hours, depending on species and conditions |

| Transfer to Agar | After germination, spores are transferred to agar plates |

| Colony Formation Time | Visible colonies appear within 24-72 hours post-transfer |

| Optimal Temperature | 25-30°C (77-86°F) for most fungi and bacteria |

| Humidity Requirement | High humidity (90-95%) for successful germination |

| Agar Type | Potato dextrose agar (PDA) or nutrient agar commonly used |

| Sterility Importance | Critical to prevent contamination during transfer |

| Species Variability | Time varies significantly between species (e.g., mushrooms vs. molds) |

| Light Exposure | Some species require light for germination, others prefer darkness |

| pH Level | Optimal pH range: 5.5-6.5 for most fungi |

| Common Challenges | Contamination, improper humidity, incorrect temperature |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Optimal Conditions for Spore Germination

Spore germination is a critical step in the cultivation process, and understanding the optimal conditions can significantly reduce the time from spore to agar colonization. Temperature plays a pivotal role, with most fungal spores germinating best between 22°C and 28°C (72°F to 82°F). Deviating from this range can either delay germination or inhibit it entirely. For example, temperatures below 20°C often slow metabolic activity, while those above 30°C may denature essential enzymes. Maintaining a consistent temperature within this window is key, and using a thermostat-controlled incubator or a warm, draft-free environment can help achieve this.

Humidity is another critical factor, as spores require moisture to activate their metabolic processes. A relative humidity of 80–90% is ideal for most species. This can be achieved by placing the agar plates in a sealed container with a damp paper towel or using a humidity-controlled chamber. However, excessive moisture can lead to contamination, so balance is crucial. For instance, lightly misting the inside of the container before sealing it ensures adequate humidity without creating a breeding ground for unwanted microbes.

Light exposure is often overlooked but can influence germination rates. While some spores require light to trigger germination, others are inhibited by it. For photodependent species, exposing the agar plates to indirect light for 12–24 hours can accelerate the process. Conversely, photophobic spores should be kept in complete darkness. Researching the specific light requirements of the species you’re working with is essential for optimal results.

Nutrient availability in the agar medium also impacts germination speed. A standard potato dextrose agar (PDA) or malt extract agar (MEA) provides sufficient nutrients for most fungal spores. However, enriching the medium with specific vitamins or minerals can enhance germination for certain species. For example, adding 0.1% yeast extract to PDA has been shown to improve germination rates in some Basidiomycetes. Always sterilize the medium properly to prevent contamination, which can derail the entire process.

Finally, time and patience are non-negotiable. While optimal conditions can reduce the time from spore to visible colonization, it still typically takes 3–14 days for most species. Regularly inspecting the plates under a sterile environment can help monitor progress without introducing contaminants. If no growth is observed after two weeks, reassess the conditions or consider using a different spore source. Consistency and attention to detail are the cornerstones of successful spore germination.

Can Pressure Canning Effectively Eliminate Spores in Home Food Preservation?

You may want to see also

Agar Preparation and Sterilization Techniques

The journey from spore to agar is a delicate dance of precision and patience, where the success of your microbial cultures hinges on the meticulous preparation and sterilization of agar. This process, often overlooked, is the cornerstone of reliable and reproducible results in microbiology. To ensure a contamination-free environment, the agar must be prepared and sterilized with utmost care, a task that demands both technical skill and an understanding of the underlying principles.

The Art of Agar Preparation: A Step-by-Step Guide

Begin by selecting the appropriate agar type for your specific microbial culture. Common choices include nutrient agar, potato dextrose agar, or selective agars like MacConkey. Weigh the required amount of agar powder, typically 15-20 grams per liter of distilled water, and dissolve it thoroughly. Heat the mixture to boiling, ensuring complete dissolution, as undissolved particles can compromise sterility. Autoclaving is the gold standard for sterilization, subjecting the agar to 121°C and 15 psi for 15-20 minutes. This process eliminates vegetative cells, spores, and other contaminants. For those without access to an autoclave, pressure cooking at 15 psi for 30 minutes can be an alternative, though less reliable.

Sterilization Techniques: A Comparative Analysis

While autoclaving is the preferred method, other techniques like dry heat sterilization (160-170°C for 2 hours) or chemical sterilization using agents like ethanol or bleach can be employed. However, these methods have limitations. Dry heat sterilization is ineffective against spores, and chemical sterilization may leave residues harmful to microbial growth. Filtration, another technique, is suitable for heat-sensitive solutions but does not sterilize the agar itself. Each method has its merits and drawbacks, emphasizing the importance of choosing the right technique for your specific application.

Troubleshooting Common Issues: Tips and Cautions

One common issue is the formation of bubbles during pouring, which can be minimized by gently swirling the agar or using a sterile, cooled inoculating loop to pop bubbles. Another challenge is maintaining sterility during the cooling process. To mitigate this, work in a sterile environment, and allow the agar to cool to around 50-55°C before pouring into plates. This temperature range is crucial, as pouring at higher temperatures can damage the agar's structure, while lower temperatures may cause premature solidification.

Optimizing Agar Quality: Practical Tips for Success

For optimal results, store agar plates at 4°C and use them within 2-4 weeks. Extended storage can lead to dehydration and contamination. When preparing multiple batches, ensure consistency by using standardized procedures and regularly calibrating equipment. Additionally, consider the age of your spores; younger spores (1-2 weeks old) generally yield better results due to their higher viability. By mastering these techniques and being mindful of potential pitfalls, you can significantly reduce the time from spore to successful agar culture, enhancing the efficiency and reliability of your microbial experiments.

Can Mold Spores Trigger Ringworm? Debunking Myths and Facts

You may want to see also

Timeframe for Visible Colony Growth

The journey from spore to visible colony on agar is a delicate dance of biology and patience, typically unfolding over 24 to 72 hours under optimal conditions. This timeframe hinges on factors like species, temperature, and agar composition. For instance, *Aspergillus niger*, a common fungus, often shows growth within 24 hours at 30°C, while slower-growing species like *Penicillium* may take up to 48 hours. Understanding this window is crucial for microbiologists and hobbyists alike, as it dictates when to inspect plates and when to adjust incubation conditions.

To expedite visible colony growth, start by ensuring spores are evenly distributed on the agar surface using a sterile spreader or swab. Incubate at species-specific temperatures—most mesophilic fungi thrive between 25°C and 30°C. Humidity control is equally vital; a dry environment can stall germination. For faster results, pre-hydrate spores in a nutrient-rich solution for 30 minutes before plating. However, avoid overcrowding the agar, as competition for resources can delay growth. Regularly inspect plates under proper lighting, as some colonies are initially translucent and easily overlooked.

Comparing fungal and bacterial growth timelines highlights the importance of patience. While bacteria like *E. coli* can form visible colonies in 12–18 hours, fungal spores often require double the time due to their complex cell walls and slower metabolic rates. This disparity underscores the need for tailored incubation strategies. For example, using a nutrient-enriched agar can shave hours off fungal growth times, but over-supplementation risks contamination. Striking this balance is key to optimizing the spore-to-colony transition.

A practical tip for monitoring growth is to mark plates with a timeline grid, noting changes daily. This visual record helps identify growth patterns and anomalies. If no colonies appear after 72 hours, reassess sterilization protocols or spore viability. For educational settings, pairing fast-growing species like *Rhizopus stolonifer* with slower ones like *Trichoderma* offers a comparative learning experience. Ultimately, visible colony growth is a testament to both the resilience of spores and the precision of cultivation techniques.

Do Clorox Wipes Effectively Kill Mold Spores? The Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Factors Affecting Spore-to-Agar Development

The time it takes for spores to develop on agar can vary significantly, influenced by a multitude of factors that dictate the success and speed of colonization. Understanding these factors is crucial for anyone working with fungi or bacteria, whether in a laboratory setting, culinary arts, or mycology. From the type of spore to environmental conditions, each element plays a pivotal role in determining how quickly and effectively spores transition to visible growth on agar.

Species and Spore Viability: Different species of fungi and bacteria have inherent variations in their growth rates and spore viability. For instance, *Aspergillus* species typically germinate within 12–24 hours, while *Trichoderma* may take 24–48 hours. Spore age and storage conditions also matter; fresh spores stored in a cool, dry place retain higher viability, reducing the time needed for germination. For optimal results, use spores no older than 6 months and store them at 4°C in a desiccated state.

Agar Composition and Nutrient Availability: The composition of the agar medium directly impacts spore development. A nutrient-rich agar, such as potato dextrose agar (PDA), accelerates growth due to its high carbohydrate and vitamin content. Conversely, minimal media may slow development. pH levels are equally critical; most fungi thrive in slightly acidic conditions (pH 5.5–6.0), while bacteria often prefer neutral pH (7.0). Adjusting these parameters can shave days off the spore-to-agar timeline.

Environmental Conditions: Temperature and humidity are non-negotiable factors. Most fungi germinate optimally between 22°C and 28°C, with deviations slowing or halting growth. For example, temperatures below 15°C can inhibit germination entirely. Humidity levels around 80–90% are ideal, as spores require moisture to activate metabolic processes. Light exposure also matters; some species, like *Neurospora*, require light for germination, while others, like *Penicillium*, are indifferent.

Inoculation Technique and Sterility: Proper inoculation technique ensures spores are evenly distributed and not damaged during transfer. Using a sterile loop or needle, lightly streak the spores across the agar surface without piercing the medium. Contamination is a common pitfall; even a single bacterial colony can outcompete fungal growth. Always work in a sterile environment, such as a laminar flow hood, and flame sterilize tools between uses.

Practical Tips for Success: To minimize development time, preheat the agar to 45°C before inoculation to prevent spore shock. Incubate plates in a sealed container to maintain humidity, and avoid frequent opening. For slow-germinating species, consider adding a thin layer of distilled water over the spores to provide immediate moisture. Regularly monitor growth, as early detection of contamination allows for timely intervention.

By meticulously controlling these factors, cultivators can significantly reduce the time from spore to visible agar colonization, ensuring efficient and successful growth. Each step, from spore selection to environmental management, contributes to a streamlined process that maximizes productivity and minimizes setbacks.

Can Spores Harm Green Giant Arborvitae? Understanding the Risks

You may want to see also

Common Mistakes in Spore-to-Agar Transfer

Spore-to-agar transfer is a delicate process that demands precision, yet even experienced cultivators often falter. One common mistake is insufficient sterilization, which can introduce contaminants that ruin the entire batch. Autoclaving substrates at 121°C for 30–60 minutes is standard, but skipping this step or using improper techniques (e.g., not sealing containers correctly) leaves spores vulnerable to bacteria and mold. Even a single contaminant can outcompete the desired fungi, rendering the agar unusable.

Another frequent error is poor technique during the transfer itself. Using a flame-sterilized inoculation loop is essential, but many rush this step, failing to cool the loop adequately before touching the spore syringe or agar surface. This can kill spores instantly or damage the agar’s integrity. A proper technique involves passing the loop through the flame until it glows, letting it cool for 10–15 seconds, and then swiftly but gently transferring the spores. Practice and patience are key to mastering this skill.

Overcrowding the agar plate is a less obvious but equally detrimental mistake. While it’s tempting to maximize spore usage, depositing too many spores in one area can lead to competition and stunted growth. A single drop from a spore syringe (approximately 0.1–0.2 mL) should be evenly distributed across the agar surface. For larger plates (100–150 mm), multiple drops can be used, but spacing is critical to ensure healthy mycelium development.

Finally, misjudging incubation time often leads to frustration. Spores typically germinate within 12–48 hours, but visible mycelium growth can take 5–14 days depending on species and conditions. Impatience may lead to premature discarding of seemingly inactive plates. Maintaining a consistent temperature (22–28°C) and humidity (60–70%) is vital, as fluctuations can delay or inhibit growth. Regular observation without disturbing the environment is the best approach to monitor progress accurately.

Avoiding these pitfalls requires attention to detail, adherence to sterile practices, and an understanding of fungal biology. By addressing these common mistakes, cultivators can significantly improve their success rate in spore-to-agar transfers, ensuring robust and contaminant-free cultures.

Troubleshooting Spore: Solutions for Missing Game After Installation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores typically germinate on agar within 12 to 48 hours, depending on the species and environmental conditions.

Factors include temperature, humidity, spore viability, agar composition, and the specific organism being cultivated.

Yes, maintaining optimal conditions such as a temperature of 25-30°C (77-86°F) and proper humidity can speed up the process.

It’s best to wait until the spores are fully hydrated and show signs of germination, usually 12 to 24 hours after inoculation.