Magic mushrooms, scientifically known as psilocybin mushrooms, grow in a fascinating and intricate process that relies on specific environmental conditions. These fungi thrive in nutrient-rich, humid environments, often found in forested areas with decaying organic matter such as wood chips, manure, or soil enriched with plant debris. The growth cycle begins with spores, which germinate under optimal temperature and moisture levels, typically between 70-75°F (21-24°C). The spores develop into mycelium, a network of thread-like structures that absorb nutrients and eventually form fruiting bodies—the mushrooms themselves. Factors like light, airflow, and substrate composition play crucial roles in their development, with many species preferring indirect light and well-aerated spaces. Cultivating magic mushrooms requires precision and patience, as their growth is highly sensitive to environmental changes, making them both a marvel of nature and a challenge to grow artificially.

Explore related products

$14.99

What You'll Learn

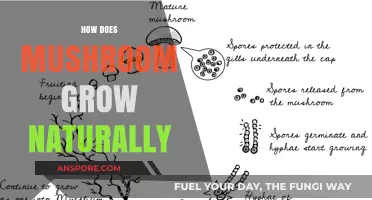

- Spores to Mycelium: Spores germinate, forming mycelium networks essential for nutrient absorption and mushroom growth

- Substrate Preparation: Properly prepared substrate (e.g., manure, grain) provides nutrients for mycelium colonization

- Environmental Conditions: Optimal temperature, humidity, and light levels are crucial for fruiting bodies to develop

- Pinning and Fruiting: Mycelium forms primordia (pins), which grow into mature mushrooms under ideal conditions

- Harvesting and Spore Release: Mushrooms release spores, completing the lifecycle, ready to start the process anew

Spores to Mycelium: Spores germinate, forming mycelium networks essential for nutrient absorption and mushroom growth

The journey of magic mushroom cultivation begins with spores, the microscopic reproductive units of fungi. When spores are released into a suitable environment, they land on a substrate and, under the right conditions, germinate. This germination process marks the initial stage of growth, where a single spore develops into a haploid cell. The cell then undergoes mitosis, dividing and extending to form the foundational structure of the fungus: the mycelium. This delicate, thread-like network is the vegetative part of the fungus and is crucial for the subsequent development of mushrooms.

For germination to occur, spores require specific environmental conditions, including adequate moisture, oxygen, and a suitable temperature range, typically between 70-75°F (21-24°C). The substrate, often a nutrient-rich material like rye grain or vermiculite, must be sterile to prevent contamination from competing microorganisms. Once a spore lands on this prepared substrate, it absorbs water, activating its metabolic processes. The emerging mycelium begins to grow, branching out in search of nutrients and colonizing the substrate. This colonization phase is vital, as the mycelium secretes enzymes to break down complex organic matter into simpler compounds that it can absorb.

As the mycelium network expands, it forms a dense, white mat known as the mycelial colony. This network is highly efficient at extracting nutrients from its environment, including carbohydrates, proteins, and minerals. The mycelium’s ability to absorb and transport these nutrients is essential for its survival and for the eventual formation of mushrooms. During this stage, maintaining optimal conditions—such as consistent moisture levels and proper ventilation—is critical to ensure healthy mycelial growth and prevent contamination.

The transition from mycelium to mushroom fruiting bodies begins once the mycelium has fully colonized the substrate and depleted its immediate nutrient sources. At this point, environmental cues such as changes in temperature, humidity, and light signal to the mycelium that it’s time to produce mushrooms. The mycelium aggregates nutrients and forms primordia, the initial structures of mushrooms, which develop into mature fruiting bodies. This process highlights the mycelium’s dual role: not only as a nutrient absorber but also as the foundation for mushroom growth.

Understanding the transformation from spores to mycelium is key to successful magic mushroom cultivation. The mycelium’s ability to form extensive networks and efficiently absorb nutrients is what sustains the fungus and enables it to produce mushrooms. By providing the right conditions and substrate, cultivators can support this natural process, ensuring robust mycelial growth and, ultimately, a bountiful harvest of magic mushrooms. This stage is both delicate and fascinating, showcasing the resilience and complexity of fungal life.

Mastering Morel Cultivation: Outdoor Growing Techniques for Abundant Harvests

You may want to see also

Substrate Preparation: Properly prepared substrate (e.g., manure, grain) provides nutrients for mycelium colonization

Substrate preparation is a critical step in cultivating magic mushrooms, as it directly influences the success of mycelium colonization and subsequent fruiting. The substrate serves as the nutrient base for the mycelium, and its quality determines the health and productivity of the mushroom culture. Commonly used substrates include manure, grain, straw, and vermiculite, each offering unique benefits. Manure, for instance, is rich in organic matter and provides a robust nutrient profile, while grain (such as rye or wheat) is often pasteurized and used for spawn production due to its high starch content. Selecting the right substrate depends on the mushroom species and the grower’s goals, but proper preparation is universal.

The first step in substrate preparation is sourcing high-quality materials. For manure-based substrates, well-aged horse or cow manure is preferred, as fresh manure can contain harmful bacteria or ammonia that may inhibit mycelium growth. Grain substrates should be clean, free from mold, and ideally organic to avoid pesticide residues. Once the materials are gathered, they must be hydrated to the correct moisture level, typically around 60-70% field capacity. This ensures the substrate is damp but not waterlogged, creating an ideal environment for mycelium to thrive. Hydration can be achieved by soaking the substrate in water or gradually misting it while mixing.

After hydration, the substrate must be pasteurized or sterilized to eliminate competing microorganisms. Pasteurization involves heating the substrate to temperatures between 60-80°C (140-176°F) for 1-2 hours, which kills most bacteria and fungi without destroying beneficial nutrients. This method is often used for manure and straw substrates. Sterilization, on the other hand, requires higher temperatures (121°C or 250°F) under pressure in an autoclave or pressure cooker, making it suitable for grain substrates. Sterilization is more thorough but also more labor-intensive and requires specialized equipment. Proper pasteurization or sterilization is essential to prevent contamination, which can derail the entire cultivation process.

Once the substrate is prepared, it must be allowed to cool to room temperature before inoculation with mushroom spawn. Introducing spawn to a hot substrate can kill the mycelium, rendering the process ineffective. After cooling, the substrate is transferred to a clean, sterile container or grow bag, and the spawn is evenly distributed throughout. The container is then sealed to maintain humidity and prevent contamination while the mycelium colonizes the substrate. This phase, known as incubation, typically takes 1-3 weeks, depending on the substrate and environmental conditions.

Properly prepared substrate not only provides essential nutrients but also creates a stable environment for mycelium growth. It ensures that the mycelium can efficiently break down the organic matter and establish a strong network, which is crucial for fruiting. By investing time and care into substrate preparation, growers can significantly increase their chances of a successful and abundant magic mushroom harvest. Attention to detail in this stage lays the foundation for healthy mycelium and, ultimately, robust mushroom yields.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: A Guide to Growing Edible Fungi at Home

You may want to see also

Environmental Conditions: Optimal temperature, humidity, and light levels are crucial for fruiting bodies to develop

Magic mushrooms, scientifically known as *Psilocybe* species, require precise environmental conditions to develop fruiting bodies successfully. Temperature plays a pivotal role in this process, with most strains thriving in a range of 70°F to 75°F (21°C to 24°C). This temperature range mimics their natural subtropical and tropical habitats, encouraging mycelium growth and fruiting. Temperatures below 65°F (18°C) or above 80°F (27°C) can stunt growth or lead to contamination. Consistency is key; fluctuations can stress the mycelium, delaying or preventing fruiting. Growers often use heating mats or thermostats to maintain optimal conditions, especially in cooler climates.

Humidity is equally critical, as magic mushrooms require a highly humid environment to initiate and sustain fruiting. Relative humidity levels should ideally range between 90% and 95% during the fruiting stage. This high humidity prevents the delicate mushroom pins from drying out and ensures proper cap and stem development. Growers achieve this by using humidifiers, misting the grow area regularly, or placing a tray of water near the mushrooms. However, excessive moisture can lead to mold or bacterial growth, so proper ventilation is essential to balance humidity levels.

Light is another essential factor, though it does not directly fuel mushroom growth as it does with plants. Instead, indirect, diffused light serves as a signal for the mycelium to initiate fruiting. A 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle is commonly used to simulate natural conditions. Bright, direct light can harm the mushrooms, while complete darkness may prevent fruiting. LED or fluorescent lights are ideal as they provide sufficient illumination without generating excessive heat. Light also helps mushrooms develop their characteristic shape and orientation, ensuring they grow upright and healthy.

The interplay between temperature, humidity, and light must be carefully managed to create a microclimate that mimics the mushrooms' natural habitat. For instance, a sudden drop in humidity or temperature can cause aborting pins, while insufficient light may result in elongated, underdeveloped fruiting bodies. Growers often use grow tents or chambers equipped with hygrometers, thermometers, and timers to monitor and adjust these conditions precisely. Patience and attention to detail are vital, as even small deviations can impact the success of the harvest.

Finally, maintaining sterile conditions alongside optimal environmental factors is crucial. Contaminants like mold or bacteria thrive in the same humid, warm conditions that mushrooms require, so cleanliness is paramount. Regularly sterilizing equipment, using filtered air, and avoiding physical contact with the growing substrate can prevent contamination. By mastering these environmental conditions and maintaining a sterile environment, growers can consistently produce healthy, robust magic mushroom fruiting bodies.

Mastering Chaga Cultivation: A Step-by-Step Guide to Growing This Medicinal Mushroom

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Pinning and Fruiting: Mycelium forms primordia (pins), which grow into mature mushrooms under ideal conditions

The process of pinning and fruiting is a critical stage in the cultivation of magic mushrooms, where the mycelium transitions from vegetative growth to reproductive development. After the mycelium has fully colonized the substrate, it begins to form primordia, commonly referred to as "pins." These pins are the earliest visible signs of mushroom formation and appear as tiny, pinhead-like structures on the surface of the substrate. Ideal conditions, including proper humidity, temperature, and fresh air exchange, are essential to trigger this stage. The mycelium senses environmental cues, such as a drop in temperature or an increase in carbon dioxide levels, which signal it to initiate fruiting.

Primordia formation is a delicate process that requires stable environmental conditions to ensure successful development. Fluctuations in humidity or temperature during this stage can cause the pins to abort or fail to mature. Maintaining a relative humidity of 90-95% and a temperature range of 70-75°F (21-24°C) is crucial for healthy pin growth. Additionally, providing adequate fresh air exchange helps prevent the buildup of carbon dioxide, which can inhibit fruiting. Growers often use techniques like fanning or opening the grow chamber periodically to ensure optimal gas exchange.

Once the primordia are established, they begin to grow rapidly into mature mushrooms, a process known as fruiting. During this phase, the mushrooms develop their characteristic caps and stems, drawing nutrients from the substrate. Light exposure, though not essential for mycelium growth, becomes important during fruiting as it helps the mushrooms orient themselves correctly and develop their typical shape and color. Indirect natural light or low-intensity artificial light is sufficient, as direct sunlight can dry out the growing environment.

The fruiting stage is also when growers must closely monitor and adjust environmental conditions to support mushroom development. Humidity levels may need to be slightly reduced to 85-90% to prevent excessive moisture buildup, which can lead to contamination or malformed mushrooms. Temperature can be slightly lowered to 68-72°F (20-22°C) to encourage slower, more robust growth. Regular misting of the mushrooms and walls of the grow chamber helps maintain humidity without waterlogging the substrate.

Harvesting should occur just before the mushroom caps fully open and release their spores, as this is when potency is typically at its peak. Gently twisting or cutting the mushrooms at the base ensures they can be harvested without damaging the mycelium or substrate, allowing for potential subsequent flushes. Properly managed, a single substrate can produce multiple flushes of mushrooms, though each flush generally yields fewer fruits than the last. Understanding and controlling the pinning and fruiting process is key to successful magic mushroom cultivation.

Discovering Chanterelle Mushrooms: Ideal Habitats and Growing Conditions Explained

You may want to see also

Harvesting and Spore Release: Mushrooms release spores, completing the lifecycle, ready to start the process anew

Magic mushrooms, like other fungi, have a lifecycle that culminates in the release of spores, ensuring the continuation of their species. Harvesting and spore release are critical stages in this process, marking the end of one generation and the beginning of the next. When the mushroom caps fully mature, they begin to release spores, which are microscopic reproductive units. This typically occurs when the cap's gills or pores, where spores are produced, start to darken or change color. For cultivators, recognizing this stage is crucial, as it signals the ideal time for harvesting if the goal is to collect spores rather than consume the mushrooms.

To harvest mushrooms for spore release, gently twist or cut the mature fruiting bodies at their base, ensuring minimal damage to the mycelium beneath. Place the harvested mushrooms on a clean surface, such as a piece of foil or glass, with the cap's underside facing down. As the mushroom dries, it will naturally release its spores, creating a visible spore print. This process usually takes 6 to 12 hours, depending on humidity and temperature. The resulting spore print can be used to propagate new mycelium, effectively restarting the lifecycle.

Spore release is the mushroom's primary method of reproduction, dispersing spores into the environment to colonize new substrates. In nature, spores are carried by air, water, or animals to suitable growing conditions, where they germinate and develop into mycelium. For cultivators, collecting spores is a deliberate process, often involving the creation of spore syringes or prints for controlled inoculation. Proper storage of spores, such as in a cool, dark place, ensures their viability for future use.

Once spores are released, the mushroom's role in the lifecycle is complete, and it begins to decompose. However, the mycelium network beneath the soil or substrate remains alive, capable of producing new fruiting bodies under the right conditions. This resilience highlights the efficiency of the fungal lifecycle, where spore release is both an ending and a beginning. By understanding and facilitating this process, cultivators can sustainably grow magic mushrooms while respecting their natural biology.

In summary, harvesting and spore release are pivotal moments in the growth of magic mushrooms, marking the completion of one lifecycle and the potential for new growth. Proper timing and technique in harvesting ensure the successful collection of spores, which can then be used to cultivate future generations. This natural process underscores the fascinating adaptability and continuity of fungi in their ecosystems.

Is Growing Mushrooms Legal? Understanding the Laws and Regulations

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Magic mushrooms thrive in a humid, sterile environment with temperatures between 70–75°F (21–24°C). They require indirect light, high humidity (around 90–95%), and a substrate rich in nutrients like vermiculite, brown rice flour, or manure.

The growth process typically takes 4–6 weeks from inoculation to harvest. Colonization of the substrate takes 2–3 weeks, followed by 1–2 weeks for pinning (formation of mushroom primordia) and another 1–2 weeks for fruiting.

Magic mushrooms can grow in the wild, often in nutrient-rich soil, wood chips, or manure. However, cultivating them indoors in a controlled environment ensures higher yields, purity, and protection from contaminants.

Spores are the reproductive units of mushrooms. They are used to inoculate a substrate, where they germinate and grow into mycelium. The mycelium then colonizes the substrate and eventually produces fruiting bodies (mushrooms). Spores alone cannot grow without a suitable substrate.