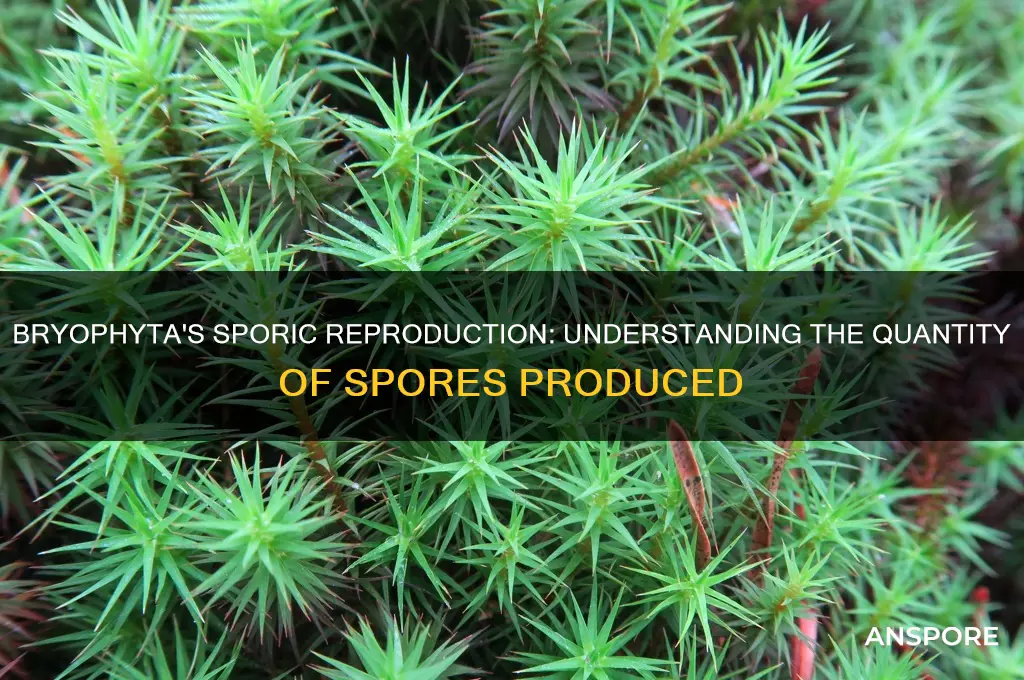

Bryophyta, commonly known as mosses, are non-vascular plants that reproduce via spores rather than seeds. Unlike vascular plants, which produce spores in large quantities, bryophytes typically generate a relatively small number of spores within specialized structures called sporangia. The exact number of spores produced can vary widely among different species of bryophytes, but generally, each sporangium may contain anywhere from a few hundred to several thousand spores. This variation depends on factors such as species, environmental conditions, and the plant's life cycle stage. Understanding the spore production in bryophytes is crucial for studying their reproductive strategies and ecological roles in various habitats.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spores Produced per Spore Capsule | Typically thousands to millions per capsule, depending on species. |

| Spore Size | Generally 10–50 micrometers in diameter. |

| Spore Type | Haploid spores (n), produced via meiosis in the sporangium. |

| Spore Dispersal Mechanism | Dispersed by wind, water, or animals; aided by elaters in some species. |

| Spore Wall Structure | Composed of sporopollenin, providing resistance to environmental stress. |

| Germination Potential | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods before germinating. |

| Species Variation | Number of spores varies widely among bryophyte species (mosses, liverworts, hornworts). |

| Ecological Role | Spores play a key role in colonization and survival in diverse habitats. |

| Reproductive Strategy | Spores are the primary means of asexual reproduction in bryophytes. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporophyte Structure: Bryophyte sporophytes have sporangia where spores develop via meiosis

- Spore Quantity per Plant: Each bryophyte sporophyte typically produces thousands to millions of spores

- Species Variation: Spore production varies widely among bryophyte species, influenced by habitat and size

- Environmental Factors: Moisture, light, and temperature affect spore development and release in bryophytes

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Bryophyte spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals for colonization

Sporophyte Structure: Bryophyte sporophytes have sporangia where spores develop via meiosis

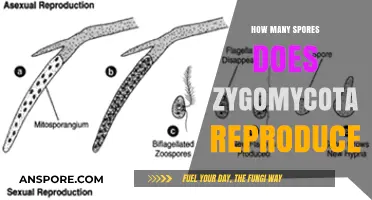

Bryophytes, a group of non-vascular plants including mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, exhibit a unique life cycle centered around their sporophyte structure. Unlike vascular plants, bryophyte sporophytes are unbranched and depend on the gametophyte for nutrition. Central to their reproductive strategy is the sporangium, a capsule-like structure where spores develop through meiosis. This process ensures genetic diversity, a critical factor for the survival of these plants in diverse environments. Understanding the sporophyte structure provides insight into how bryophytes thrive despite their simple morphology.

The sporangium in bryophytes is not merely a container for spore production; it is a highly specialized organ designed for efficient dispersal. In mosses, for instance, the sporangium is borne on a seta, a stalk-like structure that elevates it above the gametophyte. This elevation aids in spore dispersal, often facilitated by wind. Liverworts and hornworts have distinct sporangial structures, but the underlying function remains the same: to protect and disseminate spores. The number of spores produced varies widely among species, with some mosses generating thousands per sporangium, while certain liverworts produce fewer but larger spores. This variation reflects adaptations to specific ecological niches.

Meiosis, the process by which spores are formed, is a cornerstone of bryophyte reproduction. Within the sporangium, sporocytes undergo meiosis to produce haploid spores, each capable of developing into a new gametophyte. This reduction in chromosome number is essential for maintaining the alternation of generations in bryophytes. Interestingly, the timing and conditions under which meiosis occurs can vary, influenced by factors such as moisture and temperature. For example, in dry conditions, spore release may be delayed until more favorable conditions arise, ensuring higher germination success.

Practical observation of bryophyte sporophytes can be a rewarding endeavor for botanists and enthusiasts alike. To study spore development, collect mature sporophytes from their natural habitat and examine them under a microscope. Look for the sporangium’s distinctive shape and note its position relative to the gametophyte. For a hands-on experiment, place a moist filter paper over a sporangium and gently tap it to release spores. Count the spores under magnification to estimate production per sporangium. This simple technique not only provides quantitative data but also deepens appreciation for the intricate reproductive mechanisms of bryophytes.

In conclusion, the sporophyte structure of bryophytes, particularly the sporangium, is a marvel of evolutionary adaptation. Through meiosis, it ensures genetic diversity and facilitates the production of spores, which are vital for the plant’s life cycle. Whether you’re a researcher or a hobbyist, exploring the sporangium offers valuable insights into the resilience and simplicity of these ancient plants. By focusing on this specific aspect, one gains a deeper understanding of how bryophytes have thrived for millions of years, despite their lack of complex vascular systems.

Can Mold Spores Survive Washing? Uncovering the Truth Behind Cleaning

You may want to see also

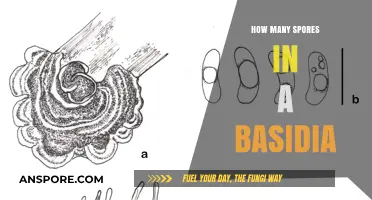

Spore Quantity per Plant: Each bryophyte sporophyte typically produces thousands to millions of spores

Bryophytes, a diverse group of non-vascular plants including mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, are remarkable in their reproductive strategies. Each bryophyte sporophyte, the spore-producing structure, is a powerhouse of dispersal, typically generating thousands to millions of spores per plant. This prodigious output ensures that even in challenging environments, bryophytes can propagate widely, colonizing new habitats with minimal energy investment. For instance, a single moss sporophyte can release up to 1.5 million spores, a number that dwarfs the reproductive output of many vascular plants.

Consider the practical implications of such high spore production. For gardeners or ecologists aiming to restore bryophyte populations, understanding this quantity is crucial. To encourage growth, collect sporophytes from healthy plants and gently shake them over bare soil or rock surfaces. Given the sheer number of spores produced, even a small area can be effectively seeded. However, caution is advised: excessive handling can damage the delicate sporophytes, reducing spore viability. Aim to collect from multiple plants to ensure genetic diversity, a key factor in resilient ecosystems.

Comparatively, the spore output of bryophytes highlights their evolutionary success in harsh conditions. Unlike vascular plants, which invest energy in seeds and protective structures, bryophytes rely on sheer numbers for survival. This strategy is particularly effective in moist, shaded environments where spores can germinate quickly. For example, in a temperate forest, a single moss sporophyte’s millions of spores can carpet the forest floor, outcompeting other species for space. This efficiency underscores why bryophytes are often pioneer species in disturbed habitats.

From an analytical perspective, the variation in spore quantity among bryophyte species offers insights into their ecological roles. Liverworts, for instance, tend to produce fewer spores per sporophyte compared to mosses, but their spores are often larger and more resilient. This trade-off between quantity and quality reflects adaptations to specific environments. Researchers studying spore dispersal can use these differences to predict how bryophytes respond to climate change or habitat fragmentation. By quantifying spore production across species, scientists can identify which bryophytes are most at risk and develop targeted conservation strategies.

In conclusion, the ability of bryophyte sporophytes to produce thousands to millions of spores per plant is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. Whether you’re a hobbyist cultivating moss gardens or a scientist studying ecosystem dynamics, this knowledge is invaluable. By leveraging this natural abundance, we can enhance biodiversity, restore degraded landscapes, and deepen our appreciation for these often-overlooked plants. Remember, in the world of bryophytes, quantity isn’t just a number—it’s a survival strategy.

Spreading Morel Spores: Techniques, Success Rates, and Best Practices

You may want to see also

Species Variation: Spore production varies widely among bryophyte species, influenced by habitat and size

Bryophytes, a diverse group of non-vascular plants including mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, exhibit remarkable variation in spore production. This diversity is not random but closely tied to ecological factors such as habitat and the physical size of the plant. For instance, species thriving in moist, shaded environments often produce fewer spores compared to those in drier, exposed areas, where higher spore counts increase the chances of successful dispersal and colonization. This adaptive strategy highlights how environmental pressures shape reproductive mechanisms in bryophytes.

Consider the habitat-driven differences in spore production. In humid tropical forests, where bryophytes are abundant, species like *Sphagnum* produce moderate spore numbers, relying on consistent moisture for spore survival. Conversely, desert-dwelling bryophytes, such as *Tortula ruralis*, often generate larger spore quantities to compensate for harsh conditions and low germination rates. This variation underscores the principle that spore production is a balance between energy investment and environmental demands, with habitat acting as a primary determinant.

Size also plays a critical role in spore production among bryophyte species. Larger plants, with more extensive photosynthetic tissue, typically allocate greater resources to spore formation. For example, the moss *Polytrichum commune*, known for its robust size, can produce up to 10,000 spores per capsule, while smaller species like *Funaria hygrometrica* yield fewer than 5,000. This correlation between size and spore output reflects the plant’s capacity to support reproductive structures, illustrating how morphological traits influence reproductive potential.

Practical observations reveal that bryophyte spore production can be optimized through habitat manipulation. Gardeners cultivating mosses, for instance, can enhance spore yield by ensuring adequate light and moisture, mimicking natural conditions favorable to the species. For *Marchantia polymorpha*, a common liverwort, maintaining a humid substrate and partial shade increases spore production significantly. Such interventions demonstrate how understanding species-specific needs can maximize reproductive success in both natural and managed environments.

In conclusion, the variation in spore production among bryophytes is a dynamic interplay of habitat and size, shaped by evolutionary adaptations to diverse environments. By examining these factors, researchers and enthusiasts alike can gain deeper insights into the reproductive strategies of these ancient plants. Whether in the wild or in cultivation, recognizing these influences allows for more effective conservation and propagation efforts, ensuring the continued survival of bryophyte species in their respective ecosystems.

Boost Your T-Score in Spore: Proven Strategies for Success

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Factors: Moisture, light, and temperature affect spore development and release in bryophytes

Bryophytes, a group of non-vascular plants including mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, produce spores as part of their reproductive cycle. The number of spores varies widely among species, with some producing as few as a few hundred and others generating tens of thousands per sporophyte. However, the development and release of these spores are not solely determined by the plant’s genetics; environmental factors play a critical role. Moisture, light, and temperature act as key regulators, influencing when and how efficiently spores are produced and dispersed. Understanding these factors is essential for both ecological studies and practical applications, such as bryophyte cultivation or conservation efforts.

Moisture is perhaps the most critical environmental factor for spore development in bryophytes. These plants are highly dependent on water for reproduction, as their spores require a moist environment to germinate and develop into gametophytes. Inadequate moisture can halt spore production entirely, while excessive waterlogging may suffocate the sporophyte, reducing spore viability. For optimal spore development, relative humidity levels should ideally range between 70–90%. In controlled environments, such as greenhouses, misting systems can be employed to maintain consistent moisture levels, ensuring sporophytes remain hydrated without becoming waterlogged. Field observations also reveal that bryophytes in humid, shaded habitats often produce more spores than those in drier areas, underscoring the direct link between moisture availability and reproductive success.

Light exposure significantly impacts the timing and efficiency of spore release in bryophytes. While these plants thrive in low-light conditions, sporophytes often require specific light cues to initiate spore maturation and dispersal. For instance, red light wavelengths have been shown to stimulate spore release in some moss species, mimicking natural sunlight signals. In contrast, prolonged exposure to intense light can desiccate the sporophyte, impairing its ability to release spores effectively. For cultivation purposes, providing 12–16 hours of diffused light daily can optimize spore production, while avoiding direct sunlight to prevent damage. This balance ensures that sporophytes receive sufficient light cues without experiencing stress, promoting healthy spore development and release.

Temperature acts as a subtle yet powerful regulator of spore development and release in bryophytes. Most species thrive in cool to moderate temperatures, typically between 15–25°C (59–77°F), which align with their natural habitats. Extreme temperatures, whether too hot or too cold, can disrupt the sporophyte’s metabolic processes, reducing spore production or causing abnormal development. For example, temperatures above 30°C (86°F) can inhibit spore maturation, while freezing conditions may damage the sporophyte’s tissues. In controlled settings, maintaining a stable temperature within the optimal range is crucial for maximizing spore yield. Seasonal variations in temperature also influence spore release timing, with many bryophytes releasing spores in spring or early summer when conditions are most favorable.

The interplay of moisture, light, and temperature creates a delicate balance that bryophytes must navigate to successfully produce and release spores. For instance, a humid environment with moderate light and cool temperatures mimics the conditions of a forest floor, ideal for spore development in many moss species. Conversely, drier conditions with higher temperatures and intense light may favor spore release in desert-adapted bryophytes, though such species are less common. Practical applications of this knowledge include designing microhabitats for bryophyte conservation, where environmental conditions can be tailored to support specific species. By manipulating these factors, researchers and enthusiasts can enhance spore production, contributing to both scientific study and the preservation of these ancient plants.

Spore Bacteria Shapes: Filament or Rod? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Bryophyte spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals for colonization

Bryophytes, including mosses, liverworts, and hornworts, produce a staggering number of spores, often ranging from thousands to millions per plant, depending on the species and environmental conditions. This prolific spore production is essential for their survival, as it increases the likelihood of successful colonization in new habitats. However, the sheer volume of spores alone is insufficient without effective dispersal mechanisms. Wind, water, and animals play pivotal roles in transporting these microscopic units to suitable environments, ensuring the continuation of bryophyte populations across diverse ecosystems.

Wind dispersal is perhaps the most common mechanism for bryophyte spores, leveraging the lightweight and minute size of the spores to maximize travel distance. Spores are released from the capsule of the sporophyte through an elastic mechanism, often aided by dry, breezy conditions. For instance, *Sphagnum* mosses, which can produce up to 1.5 million spores per capsule, rely heavily on wind to disperse their spores across peatlands and wetlands. To optimize wind dispersal, bryophytes often grow in open, elevated habitats where air currents are strong. Gardeners and conservationists can mimic this by planting bryophytes on exposed slopes or using raised substrates to enhance spore dispersal in cultivated environments.

Water dispersal is another critical mechanism, particularly for bryophytes in aquatic or riparian habitats. Spores of species like *Marchantia* liverworts are often hydrophobic, allowing them to float on water surfaces until they reach a suitable substrate. In flooded areas, water currents can carry spores over significant distances, facilitating colonization of new sites. For example, in laboratory experiments, *Pellia* liverwort spores have been shown to remain viable after being submerged in water for several days. When reintroducing bryophytes to restored wetlands, introducing spores during the wet season can capitalize on this natural dispersal method, increasing the chances of successful establishment.

Animal-mediated dispersal, though less common, is a fascinating and underappreciated mechanism. Small invertebrates, such as mites and springtails, can inadvertently carry spores on their bodies as they move through bryophyte mats. Additionally, birds and mammals may transport spores in their feathers or fur, particularly in dense, humid environments where bryophytes thrive. A study on *Funaria* moss revealed that ants can carry spores over short distances, aiding in localized colonization. To encourage animal-mediated dispersal, conservation efforts should focus on preserving biodiversity, as a rich invertebrate population can significantly enhance spore movement in bryophyte-dominated ecosystems.

Understanding these dispersal mechanisms is crucial for both scientific research and practical applications. For instance, in bryophyte conservation, knowing the primary dispersal method of a species can inform strategies for habitat restoration or reintroduction. Similarly, in horticulture, manipulating environmental conditions to favor wind or water dispersal can improve the success of moss gardens or green roofs. By harnessing the natural mechanisms of spore dispersal, we can ensure the resilience and proliferation of bryophytes, which play vital roles in ecosystem functions such as water retention, soil stabilization, and carbon sequestration.

Can Coffee Kill Spores? Uncovering the Truth Behind This Claim

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

In Bryophyta, the number of spores produced varies by species, but typically, a single sporophyte can produce thousands to millions of spores, depending on its size and environmental conditions.

The number of spores produced in Bryophyta is influenced by factors such as the size of the sporophyte, availability of water, nutrient levels, and overall health of the plant.

The spores produced in Bryophyta are haploid, as they are formed through meiosis in the sporophyte generation and develop into the gametophyte stage of the life cycle.