Identifying edible mushrooms in Connecticut requires careful attention to detail and a solid understanding of local fungi species. The state’s diverse ecosystems, ranging from deciduous forests to wetlands, support a variety of mushrooms, but not all are safe to consume. Key steps include learning to recognize common edible species like the chanterelle, oyster mushroom, and lion’s mane, while avoiding toxic look-alikes such as the jack-o’-lantern or destroying angel. Essential tools for identification include a field guide, magnifying glass, and knowledge of spore color, gill structure, and habitat. Always cross-reference findings with multiple reliable sources and, when in doubt, consult an experienced mycologist. Foraging responsibly also means respecting nature by not over-harvesting and ensuring proper permits are obtained if foraging on public or private lands.

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

$18.32 $35

What You'll Learn

- Common Edible Species: Learn about Connecticut's safe mushrooms like morels, chanterelles, and oyster mushrooms

- Toxic Look-Alikes: Identify dangerous doubles like false morels and poisonous amanitas to avoid mistakes

- Habitat Clues: Understand where edible mushrooms grow, such as in woodlands, meadows, or on trees

- Seasonal Timing: Know when to forage, typically spring and fall, for peak mushroom availability

- Physical Characteristics: Check cap shape, gill color, spore print, and stem features for accurate ID

Common Edible Species: Learn about Connecticut's safe mushrooms like morels, chanterelles, and oyster mushrooms

Connecticut's forests and fields are home to a variety of edible mushrooms, each with unique characteristics that make them both fascinating and rewarding to forage. Among the most sought-after species are morels, chanterelles, and oyster mushrooms, all of which thrive in the state’s temperate climate and diverse ecosystems. Identifying these mushrooms correctly is crucial, as misidentification can lead to serious health risks. Let’s explore these species in detail, focusing on their distinct features and habitats.

Morels (Morchella spp.) are a forager’s prize, prized for their earthy flavor and honeycomb-like caps. In Connecticut, they typically emerge in spring, favoring deciduous woods, especially near ash, elm, and oak trees. To identify morels, look for a conical cap with a spongy, ridged, and pitted texture. True morels have a hollow stem and cap, distinguishing them from false morels, which often have a wrinkled, brain-like appearance and can be toxic. Always cut a morel in half to confirm its hollow structure before consuming. Morels are best sautéed or dried for later use, but avoid eating them raw, as they can cause digestive discomfort.

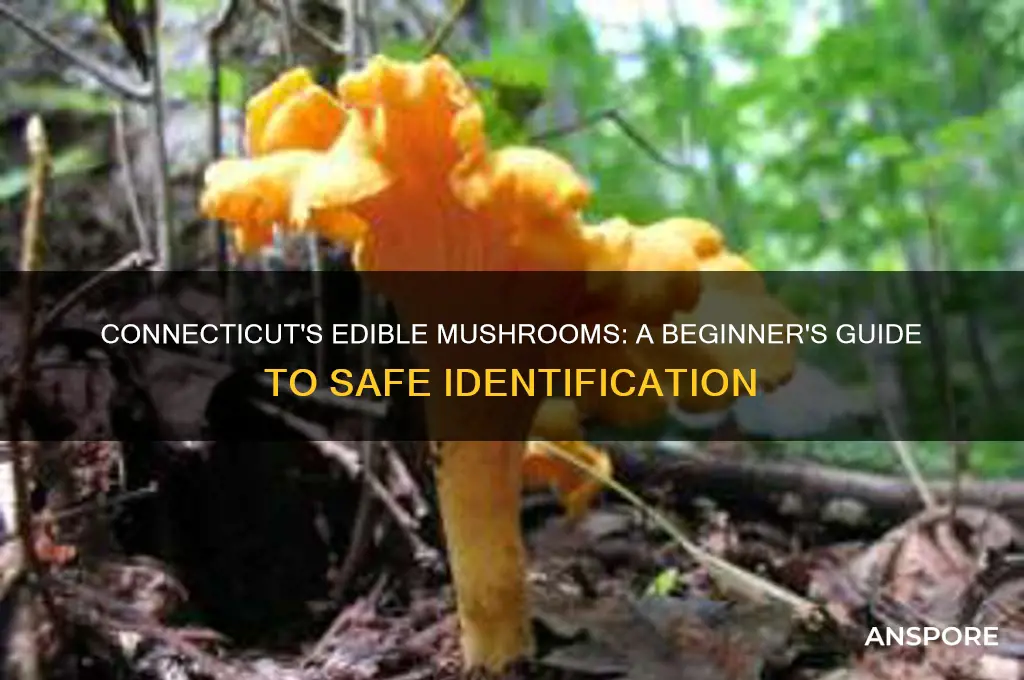

Chanterelles (Cantharellus spp.) are another Connecticut favorite, known for their golden-yellow color and fruity aroma. These mushrooms grow in wooded areas, often near coniferous or hardwood trees, from late summer to fall. Chanterelles have a forked, wavy cap and a smooth, ridged underside with false gills that extend down the stem. Their texture is chewy yet tender when cooked. To identify them, check for their apricot-like scent and ensure the gills are not sharply separated from the stem, which could indicate a look-alike species like the Jack-O-Lantern mushroom, which is toxic. Chanterelles pair well with creamy sauces or scrambled eggs, enhancing their rich flavor.

Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) are named for their shell-like shape and are one of the easiest edible species to identify. They grow in clusters on decaying wood, often on beech or oak trees, from late spring to fall. Their caps are smooth, ranging from grayish-brown to pale white, with a short, stubby stem or no stem at all. Oyster mushrooms have a mild, anise-like flavor and a tender texture, making them versatile in cooking. To avoid confusion with toxic look-alikes like the elm oyster, ensure the gills are decurrent (running down the stem) and the mushroom lacks a strong, unpleasant odor. These mushrooms are excellent sautéed, grilled, or used in soups.

When foraging for these species, always follow ethical practices: harvest only what you need, avoid damaging the mycelium, and never pick mushrooms from contaminated areas. Additionally, carry a field guide or use a reliable app to cross-reference your findings. While morels, chanterelles, and oyster mushrooms are safe and delicious, their look-alikes can be harmful. If in doubt, consult an expert or leave the mushroom undisturbed. With patience and knowledge, foraging in Connecticut can be a rewarding way to connect with nature and enrich your culinary adventures.

Are Ganoderma Mushrooms Edible? Exploring Their Safety and Culinary Uses

You may want to see also

Toxic Look-Alikes: Identify dangerous doubles like false morels and poisonous amanitas to avoid mistakes

In the lush forests of Connecticut, the allure of wild mushrooms can be irresistible, but not all that glitters is gold. Among the edible treasures lurk toxic look-alikes, such as false morels and poisonous amanitas, which can deceive even seasoned foragers. These doppelgängers often mimic the appearance of prized species, making identification a matter of life and death. For instance, false morels (Gyromitra species) resemble true morels but contain a toxin called gyromitrin, which can cause severe gastrointestinal distress, seizures, and even organ failure if consumed in sufficient quantities. Similarly, amanitas, with their elegant caps and gills, can easily be mistaken for edible varieties like the meadow mushroom, yet some species, such as the "Death Cap" (Amanita phalloides), contain amatoxins that can lead to liver and kidney failure within 48 hours.

To avoid these perilous mistakes, start by mastering the subtle distinctions between toxic and edible species. False morels, for example, often have a brain-like, wrinkled appearance compared to the honeycomb texture of true morels. Additionally, false morels typically have a reddish-brown hue and a brittle stem, whereas true morels are usually tan or brown with a more hollow, spongy structure. When examining amanitas, look for key identifiers like the presence of a volva (a cup-like structure at the base) and a ring on the stem, both of which are absent in most edible mushrooms. The Death Cap, in particular, has a greenish-yellow cap and a distinct skunk-like odor, which can serve as a warning sign. Always cross-reference multiple field guides or consult an expert if uncertainty arises.

A practical tip for foragers is to adopt a "better safe than sorry" mindset. Never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Even experienced foragers can make errors, so it’s wise to carry a field guide or use a reliable mobile app for on-the-spot verification. If you’re new to mushroom hunting, consider joining a local mycological society or attending a foraging workshop to learn from experts. Additionally, avoid foraging in areas contaminated by pollutants, as mushrooms readily absorb toxins from their environment, compounding the risk of poisoning.

Understanding the symptoms of mushroom poisoning is equally crucial. Ingesting false morels can lead to symptoms within 6–12 hours, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and dizziness. Amatoxin poisoning from amanitas, on the other hand, may not manifest for 6–24 hours, starting with gastrointestinal symptoms but progressing to severe liver damage, jaundice, and potentially fatal complications. If poisoning is suspected, seek immediate medical attention and, if possible, bring a sample of the consumed mushroom for identification.

In conclusion, while Connecticut’s forests offer a bounty of edible mushrooms, the presence of toxic look-alikes demands vigilance and knowledge. By learning the distinct features of false morels and poisonous amanitas, adopting cautious foraging practices, and staying informed about poisoning symptoms, you can safely enjoy the thrill of mushroom hunting without falling victim to dangerous doubles. Remember, the goal is not just to find mushrooms but to find the *right* mushrooms.

Are Boletus Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Identification and Consumption

You may want to see also

Habitat Clues: Understand where edible mushrooms grow, such as in woodlands, meadows, or on trees

Edible mushrooms in Connecticut often reveal themselves through their preferred habitats, each species carving out a niche in the state’s diverse ecosystems. Woodlands, for instance, are a treasure trove for foragers, with species like the prized *Lactarius indigo* (blue milk mushroom) thriving in deciduous forests. These mushrooms form symbiotic relationships with tree roots, particularly oak and beech, making them more likely to appear in mature, undisturbed woods. Conversely, meadows and grassy areas host species such as *Agaricus campestris* (field mushroom), which prefers open, sunny environments with rich, loamy soil. Understanding these habitat preferences narrows your search and increases the likelihood of a successful—and safe—foraging expedition.

Trees themselves are another critical habitat clue, as many edible mushrooms grow directly on wood, either as parasites or decomposers. The *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushroom) is a prime example, often found in clusters on decaying hardwoods like maple or beech. Similarly, *Grifola frondosa* (hen of the woods) forms large, cascading clusters at the base of oak trees in the fall. However, not all tree-dwelling mushrooms are edible; some, like the *Laetiporus sulphureus* (chicken of the woods), while edible for most, can cause reactions in sensitive individuals. Always verify the species and its relationship to its host tree before harvesting.

Foraging in Connecticut’s meadows requires a different mindset. Here, the soil composition and moisture levels dictate what grows. *Calvatia gigantea* (giant puffball), for example, favors well-drained, nutrient-rich soil and often appears after late summer rains. When hunting in meadows, look for areas with a history of agricultural use, as these tend to have the fertile soil mushrooms crave. However, be cautious of pesticide use in such areas, as chemicals can accumulate in fungal tissues. Always wash meadow-harvested mushrooms thoroughly and consider testing a small portion for tolerance before consuming.

Finally, consider the microhabitats within these broader environments. Edible mushrooms often cluster near specific features, such as fallen logs, stream banks, or the north-facing slopes of hills, where moisture levels remain consistent. For instance, *Cantharellus lateritius* (smooth chanterelle) prefers moist, shaded areas under conifers, while *Hydnum repandum* (hedgehog mushroom) is commonly found in mossy patches. By observing these microhabitats, you can refine your search and avoid wasting time in less promising areas. Remember, habitat knowledge is not just about finding mushrooms—it’s about understanding their ecology, which is key to sustainable and safe foraging.

Are Mushrooms with Pink Gills Safe to Eat? A Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$10.07 $25.99

Seasonal Timing: Know when to forage, typically spring and fall, for peak mushroom availability

In Connecticut, the rhythm of mushroom foraging aligns closely with the state’s temperate climate, where spring and fall emerge as the prime seasons for abundant growth. Spring, particularly April through June, marks the awakening of mycelium networks as soil temperatures rise and moisture from melting snow or spring rains creates ideal conditions. Morel mushrooms, a forager’s prized find, typically appear in May, favoring deciduous woodlands with well-drained soil. Fall, from September to November, brings cooler temperatures and increased humidity, triggering a second wave of fruiting bodies. This season is dominated by species like chanterelles, oyster mushrooms, and hen-of-the-woods, often found at the base of oak or beech trees. Understanding these seasonal patterns ensures foragers maximize their chances of success while minimizing the risk of encountering underdeveloped or decaying specimens.

Analyzing the science behind these seasons reveals a delicate interplay of environmental factors. Mushrooms thrive when soil temperatures range between 50°F and 70°F, a threshold consistently met during Connecticut’s spring and fall. In spring, daylight hours increase, stimulating photosynthesis in symbiotic trees and providing energy for mycorrhizal fungi. Fall’s shorter days and cooler nights create a different dynamic, encouraging saprotrophic species to decompose fallen leaves and wood. Rainfall plays a critical role in both seasons, with 1–2 inches of precipitation per week acting as a catalyst for mushroom emergence. Foragers should monitor local weather patterns and plan expeditions 3–5 days after significant rain, when mushrooms are fully developed but not yet spoiled.

Foraging in these peak seasons requires strategic planning and ethical practices. In spring, focus on south-facing slopes that warm earlier, and in fall, prioritize areas with abundant leaf litter or standing deadwood. Always carry a field guide or use a reliable app to cross-reference findings, as some toxic species mimic edible varieties. For instance, false morels resemble true morels but have a wrinkled, brain-like appearance and should never be consumed. Harvest sustainably by using a knife to cut mushrooms at the base, preserving the mycelium for future growth. Limit collection to 1–2 pounds per species per outing to avoid depleting local populations.

Comparing spring and fall foraging reveals distinct advantages and challenges. Spring offers fewer competing foragers and a higher likelihood of finding morels, but the season is shorter and more weather-dependent. Fall provides greater diversity and longer-lasting fruiting periods but attracts more foragers and insects. Both seasons demand vigilance, as toxic species like Amanita species are also active. For beginners, fall may be more forgiving due to the abundance of easily identifiable varieties like oyster mushrooms, while spring requires sharper identification skills. Regardless of season, always cook wild mushrooms thoroughly, as many edible species contain compounds that can cause digestive upset when raw.

Ultimately, mastering seasonal timing transforms mushroom foraging from a gamble into a predictable and rewarding pursuit. By aligning expeditions with Connecticut’s natural cycles, foragers not only increase their yield but also deepen their connection to the ecosystem. Spring and fall each offer unique opportunities to witness the forest’s hidden treasures, from the elusive morel to the majestic hen-of-the-woods. Armed with knowledge, respect for nature, and a keen eye, anyone can safely enjoy the bounty of these seasons while contributing to the conservation of these fascinating organisms.

Can You Eat Shiitake Mushroom Stems? A Complete Edibility Guide

You may want to see also

Physical Characteristics: Check cap shape, gill color, spore print, and stem features for accurate ID

The cap, often the most noticeable part of a mushroom, comes in various shapes: convex, flat, bell-shaped, or even umbrella-like. In Connecticut, edible species like the Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus) have distinctive, cascading spines instead of a smooth cap, while the Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius) features a wavy, golden cap. Observing whether the cap is smooth, scaly, or slimy, and noting its size and color, can narrow down possibilities. For instance, a bright red cap with white dots might signal the toxic Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria), while a creamy-white cap could indicate the edible Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). Always cross-reference cap shape with other features to avoid misidentification.

Gills, the thin, blade-like structures under the cap, are crucial for spore production and can vary in color, spacing, and attachment to the stem. Edible mushrooms like the Morel (Morchella spp.) lack gills entirely, instead having a honeycomb-like structure. In contrast, the edible Shiitake (Lentinula edodes) has closely spaced, white gills. Gill color can range from white to pink, brown, or even black, and changes as the mushroom matures. For example, young Chanterelles have pale gills that darken with age. Always examine gill attachment—are they free, attached, or decurrent?—as this detail can distinguish between similar-looking species, such as the edible Honey Mushroom (Armillaria mellea) and the toxic Galerina marginata.

A spore print is a simple yet definitive tool for identification. To create one, place the cap gills-down on a piece of paper or glass for several hours. Edible mushrooms like the Portobello (Agaricus bisporus) produce a dark brown spore print, while the toxic Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera) yields a pure white one. This method reveals spore color, which is consistent within species. For instance, a purple spore print is a hallmark of the edible Laccaria amethystina. Always handle mushrooms carefully during this process, as some toxic species can cause skin irritation.

The stem, or stipe, provides critical clues: its shape, color, texture, and presence of a ring or bulbous base. Edible mushrooms like the King Bolete (Boletus edulis) have a thick, spongy stem, while the toxic Amanita species often feature a bulbous base and a fragile ring. Note if the stem is hollow, fibrous, or solid, and whether it bruises when handled. For example, the edible Puffball (Calvatia gigantea) has a thick, solid stem, whereas the toxic Amanita ocreata’s stem is slender and fragile. Always inspect the stem’s base, as hidden features like rhizomorphs (root-like structures) can confirm a mushroom’s identity.

Combining these physical characteristics—cap shape, gill color, spore print, and stem features—creates a comprehensive profile for accurate identification. For instance, a mushroom with a convex cap, white gills, a brown spore print, and a smooth stem might be the edible Agaricus campestris. However, a similar-looking mushroom with a bulbous base and white spore print could be the deadly Amanita virosa. Always consult field guides or apps like iNaturalist for verification, and when in doubt, avoid consumption. Practice makes perfect, and consistent observation of these features will sharpen your foraging skills in Connecticut’s diverse woodlands.

Exploring the Diverse World of Edible Mushrooms: Varieties and Types

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Common edible mushrooms in Connecticut include the Morel (Morchella spp.), Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius), Lion's Mane (Hericium erinaceus), Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus), and Chicken of the Woods (Laetiporus sulphureus). Always verify identification with a field guide or expert.

Safely identify mushrooms by using reliable field guides, consulting with experienced foragers, and attending local mycology classes. Key features to check include cap shape, gill structure, spore color, stem characteristics, and habitat. Never eat a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity.

Yes, there are poisonous mushrooms in Connecticut that resemble edible species. For example, false morels (Gyromitra spp.) can look similar to true morels but are toxic. Jack-O’-Lantern mushrooms (Omphalotus olearius) resemble chanterelles but are poisonous. Always double-check identification.

The best time for mushroom foraging in Connecticut is typically late summer to early fall, though some species like morels appear in spring. Weather conditions, such as rainfall and temperature, also play a significant role in mushroom growth.

While smartphone apps can be helpful tools, they should not be solely relied upon for identification. Apps like iNaturalist or Mushroom ID can assist, but always cross-reference findings with a physical field guide or expert to ensure accuracy and safety.