Identifying edible mushrooms in Ontario requires careful attention to detail and a solid understanding of local fungi species. With over 3,000 mushroom varieties in the province, many are toxic or inedible, making accurate identification crucial for safety. Key factors to consider include the mushroom's cap shape, color, and texture, as well as its gills, stem, and spore print. Familiarity with common edible species like the Chanterelle, Morel, and Oyster mushroom is essential, as is learning to distinguish them from dangerous look-alikes such as the Jack-O’-Lantern or Destroying Angel. Always consult reliable field guides, join local mycological clubs, and, when in doubt, avoid consumption to ensure a safe and rewarding foraging experience.

Explore related products

$14.03

What You'll Learn

- Common Edible Species: Learn key characteristics of popular edible mushrooms like Chanterelles, Morels, and Oyster mushrooms

- Toxic Look-Alikes: Identify dangerous mushrooms that resemble edible ones, such as False Morels and Jack-O-Lanterns

- Habitat Clues: Understand where edible mushrooms grow, such as in forests, on trees, or near specific plants

- Seasonal Timing: Know when to forage for edible mushrooms in Ontario, typically spring to fall

- Physical Features: Focus on spore color, gill structure, cap shape, and stem characteristics for accurate identification

Common Edible Species: Learn key characteristics of popular edible mushrooms like Chanterelles, Morels, and Oyster mushrooms

Ontario's forests and fields are home to a variety of edible mushrooms, each with distinct features that can help foragers distinguish them from toxic look-alikes. Among the most sought-after are Chanterelles, Morels, and Oyster mushrooms, prized for their flavor and culinary versatility. Identifying these species accurately is crucial, as misidentification can lead to serious health risks. Let’s explore their key characteristics to ensure safe and successful foraging.

Chanterelles (Cantharellus cibarius) are often called the "golden mushroom" due to their vibrant yellow-orange color. Their most distinctive feature is their forked or wrinkled gills, which run down the stem, unlike the blade-like gills of many other mushrooms. Chanterelles have a fruity aroma, often compared to apricots, and a chewy texture when cooked. They thrive in coniferous and deciduous forests, typically appearing in late summer to fall. To identify them, look for a smooth cap with wavy edges and a tapered stem. Avoid false chanterelles, which have true gills and a more brittle texture. Always cook chanterelles thoroughly, as consuming them raw can cause digestive discomfort.

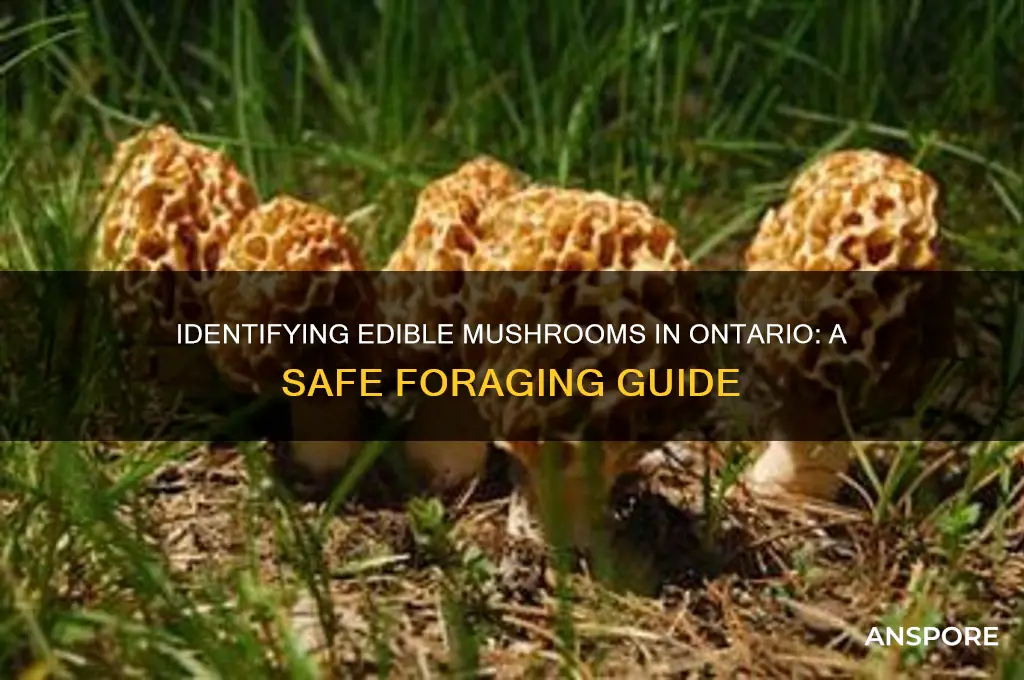

Morels (Morchella spp.) are a springtime delicacy, known for their honeycomb-like caps and hollow stems. Their spongy, cone-shaped caps are riddled with pits and ridges, making them easy to distinguish from other mushrooms. Morels grow in wooded areas, often near ash, elm, or apple trees. When foraging, ensure the mushroom is truly hollow by cutting it in half lengthwise; false morels are often partially filled with cotton-like material and can be toxic. Always cook morels well, as raw or undercooked morels can cause nausea. Their earthy, nutty flavor makes them a favorite in sauces, soups, and omelets.

Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) are named for their shell-like caps, which resemble oysters. They grow in fan-like clusters on dead or dying hardwood trees, particularly beech and oak. Their caps range from grayish-brown to white, with a smooth, velvety texture. The gills are decurrent, meaning they extend down the stem. Oyster mushrooms have a mild, anise-like flavor and a tender texture when cooked. To identify them, look for their lateral attachment to wood and the absence of a ring or volva on the stem. These mushrooms are versatile in the kitchen, often used in stir-fries, soups, and as a meat substitute.

When foraging for these species, always follow best practices: carry a reliable field guide, use a knife to cut mushrooms at the base to preserve the mycelium, and avoid over-harvesting. While Chanterelles, Morels, and Oyster mushrooms are generally safe, double-check your findings with multiple sources or consult an expert if unsure. Proper identification ensures a rewarding foraging experience and delicious culinary results.

Are Suillus Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging

You may want to see also

Toxic Look-Alikes: Identify dangerous mushrooms that resemble edible ones, such as False Morels and Jack-O-Lanterns

In the lush forests of Ontario, the allure of foraging for wild mushrooms can quickly turn perilous if you mistake a toxic look-alike for an edible species. False Morels (Gyromitra spp.) and Jack-O-Lanterns (Omphalotus olearius) are prime examples of mushrooms that mimic their safe counterparts but harbor dangerous toxins. False Morels, with their brain-like, wrinkled caps, resemble true Morels (Morchella spp.), but contain gyromitrin, a toxin that breaks down into monomethylhydrazine, a compound used in rocket fuel. Ingesting False Morels can lead to severe gastrointestinal distress, seizures, and even organ failure if consumed in large quantities. Similarly, Jack-O-Lanterns, with their bright orange, bioluminescent gills, are often confused with Chanterelles (Cantharellus spp.), but contain illudins, toxins that cause vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration.

To avoid these toxic imposters, focus on key distinguishing features. False Morels have a brittle, reddish-brown cap with deep folds, while true Morels have a honeycomb-like structure and a more uniform, hollow stem. Always cut mushrooms in half lengthwise for inspection; False Morels often have a cottony, chambered interior, whereas true Morels are completely hollow. Jack-O-Lanterns grow in clusters on wood, have true gills (unlike the forked ridges of Chanterelles), and emit a faint green glow in the dark. Chanterelles, on the other hand, have a fruity aroma, false gills, and typically grow singly or in small groups on the forest floor.

If you suspect you’ve ingested a toxic look-alike, act quickly. Symptoms from False Morels can appear within 6–12 hours, while Jack-O-Lantern poisoning usually manifests within 30 minutes to 4 hours. Contact your local poison control center immediately and provide as much detail as possible about the mushroom consumed. In severe cases, hospitalization may be necessary for supportive care, including fluid replacement and, in rare instances, liver or kidney support.

Foraging safely requires more than a casual glance. Carry a detailed field guide or use a trusted mushroom identification app, but never rely solely on digital tools. When in doubt, consult an experienced mycologist or local foraging group. Always cook mushrooms thoroughly before consumption, as heat can break down some toxins, though this is not a foolproof method for all species. Remember, the goal is not just to identify edible mushrooms but to eliminate the dangerous ones that masquerade as safe.

Finally, adopt a mindset of caution rather than confidence. The consequences of misidentification can be severe, and no meal is worth risking your health. Start by learning the most common toxic look-alikes in Ontario, such as False Morels and Jack-O-Lanterns, and practice identifying them in the field. Over time, this knowledge will become second nature, allowing you to forage with greater safety and enjoyment.

Are All Oyster Mushrooms Edible? A Comprehensive Guide to Safety

You may want to see also

Habitat Clues: Understand where edible mushrooms grow, such as in forests, on trees, or near specific plants

Edible mushrooms in Ontario often reveal themselves through their habitat preferences, acting as silent indicators of the ecosystem’s health. Forests, particularly deciduous and mixed woodlands, are prime hunting grounds. Species like the prized chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) thrive in the acidic soil beneath oak, beech, and birch trees, forming symbiotic relationships with these hosts. Coniferous forests, on the other hand, shelter varieties such as the pine mushroom (*Tricholoma magnivelare*), which prefers the company of spruce and pine. Observing the tree species in an area can narrow down potential finds, turning a random search into a targeted quest.

Beyond forests, edible mushrooms also colonize unique niches, such as decaying wood or specific plant communities. Oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) are often found on dead or dying hardwood trees, their fan-shaped caps clinging to bark like aquatic creatures. Similarly, the lion’s mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*) favors older, standing beech trees, its cascading spines resembling a shaggy mane. Even grassy areas near forests can yield surprises, like the meadow mushroom (*Agaricus campestris*), which emerges after rain in open fields. Understanding these microhabitats transforms the landscape into a map of potential discoveries.

Foraging safely requires more than recognizing habitats—it demands caution. Some toxic species mimic edible ones by growing in similar environments. For instance, the jack-o’-lantern mushroom (*Omphalotus olearius*) resembles the oyster mushroom but grows in clusters on wood and glows faintly in the dark, a warning sign. Always cross-reference habitat clues with other identification features, such as spore color, gill structure, and odor. A field guide or expert consultation is invaluable, especially for beginners, to avoid dangerous look-alikes.

Practical tips can enhance your foraging success. Carry a notebook to record habitats where you find edible species, noting tree types, soil conditions, and nearby plants. For example, morels (*Morchella* spp.) often appear in recently disturbed areas, such as burned forests or riverbanks, while truffles (*Tuber* spp.) form underground near specific tree roots, requiring a trained dog or pig to locate. Seasonality matters too: spring favors morels, while fall is prime time for chanterelles and boletes. Equip yourself with a knife, basket (for airflow), and gloves, and always forage sustainably, leaving enough mushrooms to spore and regenerate.

In conclusion, habitat clues are a forager’s compass, guiding them to edible mushrooms while minimizing risks. By studying the relationships between fungi and their environments, you’ll not only identify species more accurately but also deepen your appreciation for Ontario’s diverse ecosystems. Remember, the forest floor is a tapestry of life—read it carefully, and it will reward you with its treasures.

Are Red Mushrooms Safe to Eat? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Seasonal Timing: Know when to forage for edible mushrooms in Ontario, typically spring to fall

Ontario's mushroom foraging season is a symphony of timing, where the forest floor transforms into a culinary treasure map from spring to fall. Each season brings a unique cast of edible characters, their emergence dictated by temperature, moisture, and the forest's awakening. Spring, with its cool, damp embrace, coaxes morels from the earth, their honeycomb caps a delicacy for the discerning forager. Summer's warmth and rain usher in chanterelles, their golden funnels glowing like miniature suns beneath the canopy. As autumn's crisp air arrives, the porcini, or cep, makes its grand entrance, its meaty texture and nutty flavor a reward for those who brave the cooler temperatures.

Foraging in spring requires patience and a keen eye. Morels, often found near deciduous trees like ash and elm, thrive in the cooler temperatures and moist conditions that follow the snowmelt. Look for their distinctive honeycomb pattern and attach to the stem, ensuring you don’t mistake them for the toxic false morel, which has a wrinkled, brain-like cap and a brittle stem. Early morning or after rain are prime times, as the mushrooms are more hydrated and easier to spot.

Summer foraging is a race against time and competition. Chanterelles, with their fruity aroma and forked gills, favor hardwood forests and can often be found near birch and oak trees. Their bright color makes them easier to spot, but their popularity means you’re not the only one searching. Arrive early, bring a basket to prevent bruising, and remember to leave some behind to allow the mycelium to continue fruiting.

Autumn is the forager’s jackpot, with a variety of mushrooms appearing as the leaves change color. Porcini, prized for their rich flavor, are often found under conifers like pine and spruce. Their thick stems and spongy pores distinguish them from look-alikes like the bitter bolete. Foraging in fall requires layering up and being prepared for unpredictable weather, but the bounty is worth the effort.

Knowing when to forage is as crucial as knowing what to look for. Each season offers a unique opportunity to connect with nature and harvest its gifts, but timing is everything. Spring’s morels, summer’s chanterelles, and fall’s porcini are not just mushrooms—they’re markers of the forest’s rhythm, a rhythm that rewards those who listen.

Are Shaggy Ink Cap Mushrooms Edible? A Tasty or Toxic Guide

You may want to see also

Physical Features: Focus on spore color, gill structure, cap shape, and stem characteristics for accurate identification

Spore color is a critical, often overlooked detail in mushroom identification. Unlike the visible cap or stem, spores are microscopic, but their color can be observed through a simple technique: place the mushroom cap on a white piece of paper, gill-side down, and leave it undisturbed for several hours. In Ontario, edible species like the Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius) typically produce white to pale yellow spores, while the toxic Amanita species often release white spores that can be a warning sign. This method, known as a spore print, is a non-destructive way to gather essential data without damaging the mushroom’s structure.

Gill structure is another key feature that varies widely among species. Edible mushrooms in Ontario, such as the Morel (Morchella spp.), have a honeycomb-like network of ridges and pits instead of traditional gills, which helps distinguish them from false morels with their brain-like, convoluted folds. In contrast, the gills of the edible Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) are decurrent, meaning they run down the stem, while the deadly Galerina marginata has gills that are adnate (attached directly to the stem). Observing gill attachment, spacing, and color can narrow down identification significantly, but always cross-reference with other features to avoid errors.

Cap shape and texture are as distinctive as fingerprints in the mushroom world. The edible Lion’s Mane (Hericium erinaceus) has a cascading, icicle-like cap with no gills, while the toxic Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria) boasts a bright red, wart-covered cap. In Ontario, the edible Puffball (Calvatia gigantea) starts as a smooth, white sphere before maturing and releasing spores. When examining caps, note details like color, margin shape (curled, flat, or upturned), and texture (smooth, scaly, or fibrous). A magnifying lens can reveal subtle features, such as tiny hairs or cracks, that are crucial for accurate identification.

Stem characteristics often provide the final piece of the puzzle. The edible Shaggy Mane (Coprinus comatus) has a tall, cylindrical stem with a distinctive shaggy skirt, while the deadly Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera) has a bulbous base and a fragile, ringed stem. In Ontario, the edible Milk Cap (Lactarius spp.) exudes a milky substance when its stem or gills are damaged, a feature absent in look-alike species. Always inspect the stem for features like color, thickness, presence of a ring or volva (cup-like base), and whether it’s hollow or solid. Combining these observations with other physical traits ensures a more confident and safe identification.

Are Parachute Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Look for features like cap shape, color, gills or pores, stem structure, spore print color, and habitat. Edible mushrooms often have consistent, identifiable traits, such as the smooth cap and gills of Agaricus species or the spongy pores of Boletus species.

Yes, several poisonous mushrooms resemble edible ones, such as the deadly Amanita species, which can look similar to Agaricus (button mushrooms) or Lepiota species. Always double-check identification and avoid mushrooms with white gills and a ring on the stem.

Field guides and apps can be helpful tools, but they should not be the sole method of identification. Always cross-reference with multiple sources, consult experts, and gain hands-on experience to ensure accuracy.

The best time for mushroom foraging in Ontario is late summer to early fall, typically from August to October. This is when conditions are ideal for mushroom growth, with cooler temperatures and adequate moisture.

There is no foolproof method to test if a mushroom is edible. Avoid tasting, smelling, or touching mushrooms as a test. Instead, rely on accurate identification through detailed observation, spore prints, and expert consultation. When in doubt, throw it out.