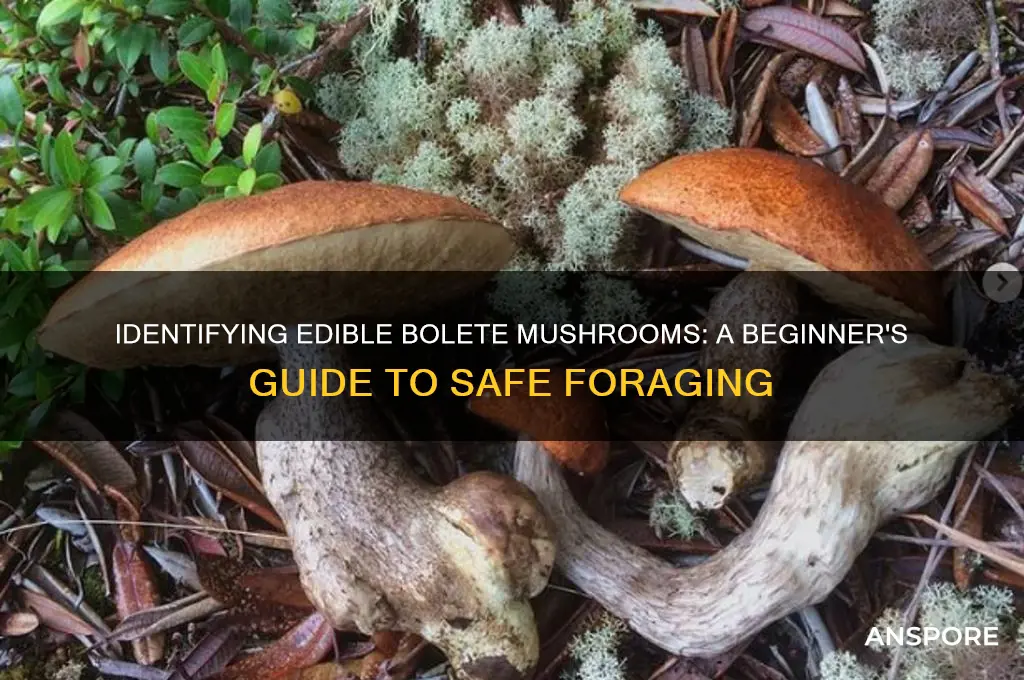

Identifying edible bolete mushrooms requires careful observation and knowledge of key characteristics. These mushrooms are distinguished by their spongy pore layer under the cap instead of gills, and they typically have a stout, often bulbous stem. To ensure safety, look for features such as a smooth or slightly netted cap, pores that are white to yellow (not red or brown), and a stem that bruises blue when handled, which is a common trait in many edible boletes. Additionally, avoid mushrooms with a bright red or orange pore surface, a slimy cap, or an unpleasant odor, as these can indicate toxicity. Always consult a reliable field guide or expert, and when in doubt, do not consume the mushroom.

Explore related products

$21.74 $24.95

What You'll Learn

- Cap features: Look for dry, smooth or slightly scaly caps, often brown, red, or white

- Pore structure: Check for sponge-like pores under the cap, not gills; color varies

- Stem characteristics: Note solid, often thick stems with or without reticulations (net-like patterns)

- Spore print: Take a spore print; boletes typically produce olive-green to brown spores

- Taste and smell: Edible boletes should smell pleasant and mild, with no bitter taste

Cap features: Look for dry, smooth or slightly scaly caps, often brown, red, or white

The cap of a bolete mushroom is its most distinctive feature, often the first thing foragers notice in the wild. When identifying edible boletes, focus on caps that are dry to the touch, with a texture ranging from smooth to slightly scaly. These caps typically present in earthy tones—browns, reds, and whites—that blend seamlessly with forest floors. Unlike slimy or sticky varieties, which often indicate non-edible species, dry caps suggest a bolete worth further inspection. This simple tactile and visual check is your first line of defense against misidentification.

Consider the *Boletus edulis*, commonly known as the porcini, a prime example of an edible bolete with a dry, brown cap. Its smooth surface and robust texture make it a forager’s favorite. In contrast, the *Boletus frostii*, with its bright red cap, showcases how color variation can still align with edibility. However, not all red-capped mushrooms are safe—always cross-reference with other features. White-capped boletes, like *Boletus barrowsii*, are less common but equally prized, though their pale hue can sometimes attract insects, so inspect carefully.

To refine your search, observe the cap’s margins and overall shape. Edible boletes often have rounded or convex caps that flatten with age, and their margins may curl slightly inward when young. Avoid caps with pronounced wrinkles or deep cracks, as these can indicate older, less palatable specimens or even non-edible species. For beginners, start with brown-capped varieties, as their color and texture are more consistent with edible traits. Always carry a field guide or use a reliable app to compare your findings.

Practical tip: When in doubt, perform a simple spore print test. Place the cap gill-side down on white paper overnight. Edible boletes typically produce brown spores, while white or colored spores may signal a different genus. Additionally, if the cap feels damp or sticky, even slightly, it’s best to err on the side of caution and leave it behind. Remember, foraging is as much about patience as it is about knowledge—take your time to observe and learn.

In conclusion, mastering cap features is a cornerstone of identifying edible boletes. Dryness, texture, and color are your primary cues, but they’re just the beginning. Combine these observations with other characteristics, like pore structure and stem features, to build confidence in your foraging skills. With practice, you’ll soon distinguish the edible treasures from their toxic counterparts, ensuring a safe and rewarding harvest.

Exploring Edible Mushrooms: How Many Can You Safely Eat?

You may want to see also

Pore structure: Check for sponge-like pores under the cap, not gills; color varies

One of the most distinctive features of bolete mushrooms is their pore structure, which sets them apart from other fungi like gilled mushrooms. Instead of the familiar gills found in species such as button or shiitake mushrooms, boletes have a spongy layer of pores beneath their caps. These pores are tiny, tube-like openings that release spores, and they feel soft and cushion-like to the touch. When identifying edible boletes, this sponge-like texture is a critical characteristic to confirm. For instance, the highly prized porcini (Boletus edulis) has a pore surface that is initially white and tight, gradually turning yellowish and more open with age. Recognizing this structure is your first step in distinguishing boletes from look-alikes.

The color of the pore surface is another variable to observe, as it can provide clues about the mushroom’s maturity and species. In young boletes, the pores are often pale, ranging from white to cream or light yellow. As the mushroom matures, the color may deepen to olive, brown, or even reddish hues, depending on the species. For example, the red-cracked bolete (Boletus chrysenteron) has a pore surface that starts as bright yellow but turns olive-green or brownish with age. Tracking these color changes can help you narrow down the identification, but always cross-reference with other features like cap color and habitat.

While the pore structure is a key identifier, it’s essential to inspect it carefully, as some toxic mushrooms can mimic boletes. For instance, the poisonous false chanterelle (Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca) has folds that resemble pores from a distance. To avoid confusion, gently press your thumb against the pore surface—a true bolete will feel soft and spongy, while a false look-alike may feel more rigid or gill-like. Additionally, always cut the mushroom in half to examine the internal structure; edible boletes typically have a uniform, fleshy texture, whereas toxic species may have distinct layers or discoloration.

Practical tips for examining pore structure include using a magnifying glass to observe the individual pores, especially in younger specimens where they are tightly packed. Note whether the pores bruise or change color when touched, as this can be a species-specific trait. For example, the bay bolete (Boletus badius) has pores that turn blue-green when bruised. Always document your findings with photos or notes, as this will help you build a reference for future forays. Remember, while pore structure is a vital identifier, it should never be the sole criterion for determining edibility—always consult a field guide or expert when in doubt.

Are Laccaria Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Their Safety and Uses

You may want to see also

Stem characteristics: Note solid, often thick stems with or without reticulations (net-like patterns)

The stem of a bolete mushroom is a critical identifier, often distinguishing edible species from their toxic counterparts. A solid, thick stem is a hallmark of many edible boletes, providing a sturdy base that supports the cap and pores. Unlike the hollow or fragile stems of some poisonous mushrooms, the robust structure of bolete stems reflects their role in nutrient transport and stability. This characteristic alone, however, is not enough for identification—it’s the combination of stem traits that matters.

Reticulations, or net-like patterns, on the stem are another key feature to observe. These patterns resemble a delicate fishnet stockings, adding texture and visual interest to the stem’s surface. Not all edible boletes have reticulations, but when present, they are a strong indicator of species like *Boletus edulis* (porcini) or *Boletus barrowsii*. To examine this, gently run your fingers along the stem—the raised ridges of the net-like pattern should be discernible. If the stem is smooth, don’t dismiss it; some edible boletes, such as *Suillus luteus*, lack reticulations but compensate with other identifying features.

When assessing stem characteristics, consider the stem’s color and how it changes with age or handling. For instance, the stem of *Boletus edulis* remains a pale cream or brown, while that of *Boletus badius* may bruise blue when damaged. A practical tip: carry a small knife to carefully slice the stem lengthwise. Edible boletes typically reveal a uniformly solid interior, whereas some toxic species may show a cottony or chambered structure. This simple step can provide valuable insight into the mushroom’s edibility.

Finally, the stem’s thickness relative to the cap size is a subtle but useful detail. Edible boletes often have stems that are proportionally thick, balancing the weight of the cap and pore surface. A disproportionately thin stem, especially in conjunction with other red flags like a slimy cap or unpleasant odor, should raise caution. By focusing on these stem characteristics—solidity, thickness, reticulations, and additional traits—you can narrow down your identification and increase confidence in foraging edible boletes safely.

Identifying Safe Wild Mushrooms: A Beginner's Guide to Edible Varieties

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$18.32 $35

Spore print: Take a spore print; boletes typically produce olive-green to brown spores

A spore print is a simple yet powerful tool in the mycologist's arsenal, offering a glimpse into the hidden world of mushroom reproduction. By examining the color and pattern of spores, you can unlock valuable insights into the identity of a bolete mushroom. This method is particularly useful when distinguishing between edible and toxic species, as spore color is a consistent and reliable characteristic.

To create a spore print, you'll need a mature mushroom with open gills or pores, a sheet of paper or glass slide, and a container to cover the mushroom. Start by placing the mushroom cap on the paper or slide, with the spore-bearing surface facing down. Ensure the cap is centered and stable. Then, cover the mushroom with the container, creating a humid environment that encourages spore release. Leave it undisturbed for several hours or overnight. When you remove the container, you should see a colorful deposit of spores on the paper or slide, revealing the mushroom's hidden palette.

The spore print of boletes is a distinctive feature, typically presenting shades of olive-green to brown. This color range is a key identifier, setting boletes apart from other mushroom families. For instance, the highly prized porcini (Boletus edulis) produces a beautiful olive-brown spore print, while the toxic Boletus satanas may display a similar color, emphasizing the importance of considering multiple identification factors. It's worth noting that spore print color can vary slightly due to environmental conditions and mushroom age, so it's best to compare your findings with established references.

Creating spore prints is an accessible and educational activity for foragers of all ages. It requires minimal equipment and provides a unique perspective on mushroom biology. However, it's essential to exercise caution when handling wild mushrooms, especially if you're new to foraging. Always ensure proper identification before consuming any mushroom, as some toxic species can closely resemble edible boletes. Combining spore print analysis with other identification techniques, such as examining cap color, pore structure, and habitat, will significantly enhance your accuracy in distinguishing edible boletes from their poisonous counterparts.

In the world of mushroom identification, the spore print is a valuable piece of the puzzle. It offers a scientific approach to a hobby that often relies on experience and intuition. By incorporating this technique into your foraging practice, you'll develop a deeper understanding of bolete mushrooms and their unique characteristics, making your culinary adventures in the wild both safer and more rewarding. Remember, the olive-green to brown spore print is a signature trait of boletes, but it's just one of many fascinating aspects to explore in the diverse kingdom of fungi.

Exploring the Edible Mushroom Varieties: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Taste and smell: Edible boletes should smell pleasant and mild, with no bitter taste

The aroma of a mushroom can be a telling sign of its edibility, especially when it comes to boletes. A pleasant, mild scent is a good indicator that you've found a choice edible. Imagine a subtle, earthy fragrance, reminiscent of a forest floor after rain—this is the olfactory experience you're aiming for. In contrast, a strong, unpleasant odor, often described as sour or pungent, could be a red flag, suggesting the presence of toxins or simply an unpalatable species. This simple sensory test is a crucial step in the identification process, allowing you to quickly eliminate potential candidates.

Taste, another sensory tool, can further confirm a bolete's edibility. A key characteristic of edible boletes is the absence of bitterness. When you find a bolete with an appealing aroma, the next step is to carefully taste a small portion of the cap. It should be mild and pleasant, with no lingering bitter aftertaste. This is a critical distinction, as many toxic mushrooms contain bitter compounds that can cause discomfort or even harm. For instance, the Bitter Bolete (*Tylopilus felleus*) lives up to its name, with a taste that can ruin a meal and potentially lead to an upset stomach.

Here's a practical tip: when testing for taste, ensure you've correctly identified the mushroom as a bolete first. Then, cut a small piece from the cap, ensuring it's free from dirt and debris. Place it on your tongue, allowing it to sit for a few seconds to get a full sense of the flavor. If it's mild and inoffensive, you're likely dealing with an edible species. However, always spit it out after tasting, as consuming raw mushrooms can sometimes cause digestive issues.

It's worth noting that while taste and smell are valuable tools, they should not be the sole means of identification. Some toxic mushrooms can have mild flavors, and relying solely on taste can be risky. Always cross-reference with other identification features, such as spore color, tube structure, and habitat. For beginners, it's advisable to consult a local mycological society or an experienced forager to learn the nuances of bolete identification, ensuring a safe and enjoyable mushroom-hunting experience.

In the world of mushroom foraging, the sense of smell and taste can be powerful allies. They provide an immediate, sensory connection to the mushroom, offering clues that visual inspection alone might miss. By understanding the subtle differences in aroma and flavor, foragers can make more informed decisions, increasing their confidence in identifying edible boletes and avoiding potential lookalikes. This sensory approach adds a layer of depth to the art of mushroom hunting, engaging multiple senses in the pursuit of a delicious, wild harvest.

Can You Eat Cremini Mushroom Stems? A Tasty Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Edible boletes typically have a spongy underside (pore surface instead of gills), a fleshy cap, and a stout stem. Look for a smooth or slightly reticulated (netted) stem, pores that are white to yellow when young, and a cap color ranging from brown to reddish-brown. Avoid any with a slimy cap, bright red pores, or a bulbous base.

Edible boletes generally have pores that do not bruise blue or brown immediately when touched. Their caps and stems should not have prominent netting or scaling. Poisonous boletes often have a blue or brown bruising reaction, a strongly reticulated stem, or a bulbous base. Always cross-reference with a reliable guide or expert.

Yes, the *Boletus edulis* (Porcini) is a popular and easy-to-identify edible bolete. It has a brown cap, white pores that turn yellow with age, and a smooth or slightly reticulated stem. Another beginner-friendly species is *Boletus barrowsii*, which has a similar appearance but is larger. Always verify with multiple sources before consuming.