Identifying yeast spores is a crucial skill in microbiology and fermentation processes, as it helps distinguish yeast from other microorganisms and ensures the purity of cultures. Yeast spores, also known as ascospores, are typically formed during the sexual reproduction phase of certain yeast species, such as *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*. To identify them, one must first examine the yeast under a microscope, looking for small, oval-shaped structures often found within asci, the sac-like structures that contain the spores. Staining techniques, such as Gram staining or ascospore staining, can enhance visibility and confirm their presence. Additionally, observing the yeast's life cycle and environmental conditions, such as nutrient availability and temperature, can provide contextual clues. Accurate identification is essential for applications in brewing, baking, and biotechnology, where yeast purity and viability directly impact product quality.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Size | Typically 2-5 μm in diameter, smaller than vegetative yeast cells |

| Shape | Generally spherical or oval, depending on the yeast species |

| Wall Thickness | Thicker cell wall compared to vegetative cells, providing resistance to harsh conditions |

| Staining | Spores often stain differently from vegetative cells; may appear more refractive or take up specific stains like ascospore-specific dyes |

| Budding | Absence of budding scars or buds, as spores are non-replicating |

| Germination | Ability to germinate under favorable conditions, forming a new vegetative cell |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to heat, desiccation, and chemicals due to their thick wall and dormant state |

| Location | Formed within asci (sac-like structures) in ascomycetes or directly on the cell in basidiomycetes |

| Microscopy | Visible under light microscopy, often requiring staining or phase-contrast techniques for clear identification |

| Molecular Markers | May have distinct genetic or molecular markers compared to vegetative cells, detectable via PCR or sequencing |

| Metabolic Activity | Minimal or no metabolic activity in the dormant state |

| Species-Specific Traits | Some species have unique spore characteristics, such as color, texture, or arrangement in asci |

What You'll Learn

- Microscopic Examination: Use a microscope to observe spore size, shape, and arrangement under high magnification

- Staining Techniques: Apply stains like lactophenol cotton blue to enhance spore visibility and structure

- Cultural Characteristics: Grow yeast on specific media to observe spore formation and colony traits

- Spore Morphology: Identify spores based on their distinct shapes, colors, and surface features

- Molecular Methods: Use PCR or DNA sequencing to confirm spore identity at the genetic level

Microscopic Examination: Use a microscope to observe spore size, shape, and arrangement under high magnification

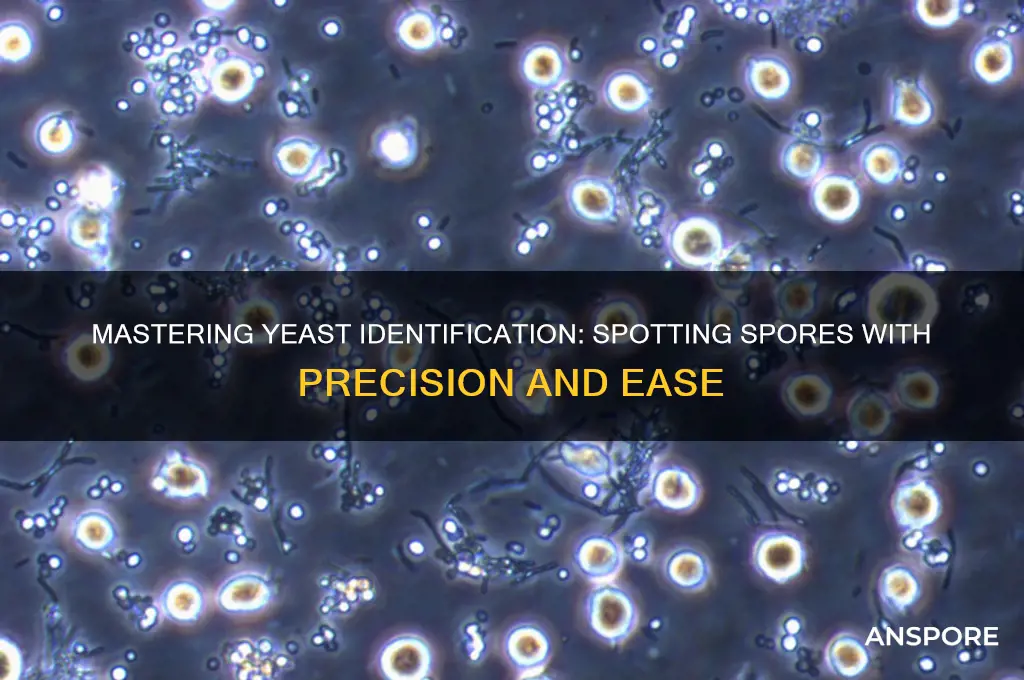

Under high magnification, yeast spores reveal intricate details that distinguish them from vegetative cells and other microorganisms. A compound microscope with at least 400x magnification is essential for clear observation, as spores typically range from 2 to 5 micrometers in diameter—smaller than the average yeast cell. Begin by preparing a wet mount slide with a stained sample, using methylene blue or cotton blue to enhance contrast. This simple step transforms the spores from nearly invisible to distinct, allowing you to assess their size, shape, and arrangement with precision.

The shape of yeast spores is a critical identifier. Unlike the round or oval vegetative cells, spores often appear elliptical or oval with a slightly pointed end, particularly in species like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*. Some spores may also exhibit a thickened, refractive wall, visible as a dark line under brightfield microscopy. Arrangement is another key feature: spores are typically produced in asci (spore-containing sacs) in ascomycetes, with 1 to 8 spores arranged linearly or in clusters. Observing these patterns can confirm the presence of spores and differentiate them from bacterial endospores or other fungal structures.

To maximize the utility of microscopic examination, follow a systematic approach. First, adjust the focus to capture the entire depth of the sample, as spores may lie at different planes. Use the fine focus knob to scan through the specimen, noting variations in spore morphology. For advanced analysis, consider using phase-contrast or differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy, which enhances the visibility of unstained spores by exploiting differences in refractive index. These techniques are particularly useful for identifying spores in their natural state without altering their structure.

Despite its effectiveness, microscopic examination has limitations. Overlapping spores or debris can obscure accurate counting or measurement, requiring careful sample preparation. Additionally, distinguishing between immature spores and mature ones demands experience, as immature spores may appear smaller or less distinct. To mitigate these challenges, compare your observations with reference images or consult taxonomic keys specific to yeast species. With practice, this method becomes a powerful tool for identifying yeast spores and understanding their role in fungal reproduction.

Surviving Flu Season: Understanding the Lifespan of Flu Spores

You may want to see also

Staining Techniques: Apply stains like lactophenol cotton blue to enhance spore visibility and structure

Yeast spores, often elusive under standard microscopy, require specialized techniques to reveal their intricate structures. Staining is a cornerstone method, transforming these microscopic entities from near-invisible to vividly detailed. Among the array of stains available, lactophenol cotton blue stands out for its ability to enhance both visibility and structural clarity. This technique is not merely about adding color; it’s about precision, ensuring that every spore’s morphology is distinctly outlined for accurate identification.

To apply lactophenol cotton blue effectively, begin by preparing a clean slide with a thin smear of the yeast sample. Heat-fix the sample gently to adhere it to the slide without distorting the spores. Add a single drop of the stain to the specimen, ensuring it spreads evenly. The stain’s composition—a blend of cotton blue, phenol, and lactic acid—penetrates the spore walls, highlighting their chitinous layers. Allow the slide to sit for 3–5 minutes, providing ample time for the stain to bind. Blot excess stain carefully with filter paper, avoiding smudges that could obscure details.

While lactophenol cotton blue is widely used, its application requires caution. Over-staining can lead to a dark, uniform background that masks spore features, while under-staining may leave spores faint and indistinct. Optimal results are achieved with a balanced approach: use a 1:1 ratio of stain to sample volume for most yeast species. For thicker samples, dilute the stain slightly with distilled water to maintain clarity. Always examine the slide under a 100X oil immersion objective to capture the fine details of spore structure, such as size, shape, and septation.

Comparatively, lactophenol cotton blue outperforms simpler stains like methylene blue in revealing spore-specific characteristics. While methylene blue provides basic contrast, it lacks the ability to differentiate chitinous layers or highlight structural nuances. Lactophenol cotton blue, however, binds selectively to these layers, producing a distinct blue coloration that delineates spore morphology. This specificity makes it an indispensable tool for mycologists and microbiologists studying yeast sporulation.

In practice, mastering this staining technique requires patience and attention to detail. Beginners should start with known yeast cultures to familiarize themselves with expected staining outcomes. For instance, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* spores will exhibit a characteristic oval shape with a prominent blue stain, while *Candida* species may show smaller, more rounded spores. Documenting results with annotated micrographs can serve as a reference for future identifications. With consistent practice, lactophenol cotton blue staining becomes a reliable method for unlocking the hidden world of yeast spores.

Understanding Plant Spores: Tiny Survival Units and Their Role in Reproduction

You may want to see also

Cultural Characteristics: Grow yeast on specific media to observe spore formation and colony traits

Yeast spores, known as ascospores or basidiospores depending on the species, are critical for identification and understanding yeast biology. To observe spore formation and colony traits, cultivating yeast on specific media is essential. Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) is a common medium for yeast cultivation, providing the carbohydrates and nutrients necessary for growth. However, to specifically induce spore formation, sporulation medium such as Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) supplemented with potassium acetate or sporulation agar (1% potassium acetate, 0.5% dextrose, 0.05% glucose, and 0.1% yeast extract) is recommended. These media mimic nutrient-depleted conditions, triggering yeast cells to enter the sporulation phase.

The process begins by inoculating the yeast onto the selected medium using a sterile loop or swab. Incubate the plates at the optimal temperature for the yeast species, typically 25–30°C, for 3–7 days. During this period, observe the colonies daily for changes in morphology. Mature colonies often exhibit a creamy or granular texture, and under a microscope, spores appear as oval or round structures within the ascus or basidium. For example, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* forms tetrads of ascospores, while *Schizosaccharomyces pombe* produces spores in a linear arrangement.

Microscopic examination is crucial for confirming spore formation. Prepare a wet mount by gently scraping a small portion of the colony with a sterile needle and suspending it in a drop of distilled water or lactophenol cotton blue stain. The stain enhances spore visibility and helps differentiate spores from vegetative cells. Under a 40x–100x objective, spores will appear as distinct, refractile bodies, often smaller than vegetative cells. For quantitative analysis, count the number of spores per ascus or basidium to confirm the spore pattern characteristic of the species.

While culturing yeast on specific media is effective, certain cautions must be observed. Contamination by bacteria or molds can interfere with spore formation and colony observation. To minimize this, use sterile techniques and include antibiotic supplements like chloramphenicol (50 mg/L) in the medium if necessary. Additionally, not all yeast species sporulate under the same conditions; some may require specific environmental cues, such as pH adjustments or exposure to stress factors like ethanol. Always consult species-specific protocols for optimal results.

In conclusion, growing yeast on tailored media provides a reliable method to observe spore formation and colony traits. By selecting the appropriate medium, maintaining sterile conditions, and employing microscopic techniques, researchers and enthusiasts can accurately identify yeast spores. This approach not only aids in taxonomic classification but also offers insights into yeast life cycles and stress responses, making it a valuable tool in both academic and industrial settings.

Can Marijuana Spores Trigger Hives? Exploring the Allergic Reaction Link

You may want to see also

Spore Morphology: Identify spores based on their distinct shapes, colors, and surface features

Yeast spores, often referred to as ascospores or basidiospores depending on the species, exhibit a remarkable diversity in morphology that can be pivotal for identification. Shape is the first characteristic to observe: ascospores are typically oval or spherical, while basidiospores may be more elongated or cylindrical. For instance, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, a common yeast in baking and brewing, produces oval ascospores arranged in a tetrad pattern. In contrast, *Schizosaccharomyces pombe* forms elongated spores with a distinct cylindrical shape. A high-magnification microscope (1000x) is essential for accurately measuring spore dimensions, which can range from 2 to 10 micrometers in length, depending on the species.

Color and pigmentation are equally diagnostic features. While many yeast spores are hyaline (colorless), some species develop distinct hues under specific conditions. For example, *Cryptococcus neoformans* produces spores with a brown capsule visible under India ink staining, a critical trait for clinical identification. Similarly, *Rhodotorula* species often exhibit pink or red spores due to the presence of carotenoid pigments. To enhance color observation, a lactophenol cotton blue stain can be applied, which not only highlights cell walls but also accentuates any natural pigmentation.

Surface features provide another layer of detail for spore identification. Smooth surfaces are common, but some spores exhibit intricate patterns. *Aspergillus* species, though not yeasts, share fungal spore characteristics like echinulated (spiny) or rough surfaces, which can serve as a comparative reference. For yeast, *Candida albicans* forms chlamydospores with a thick, rough outer wall, while *Debaryomyces hansenii* spores may appear slightly wrinkled under high magnification. A scanning electron microscope (SEM) can reveal ultrastructural details, such as pores or ridges, that are invisible under light microscopy.

Practical tips for accurate identification include preparing a wet mount with a 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution to dissolve background debris and enhance spore visibility. For color analysis, compare samples under both brightfield and phase-contrast microscopy to capture subtle differences. When documenting morphology, sketch or photograph spores at multiple focal planes to capture three-dimensional features. Cross-referencing observations with databases like the *Atlas of Clinical Fungi* or *The Yeasts: A Taxonomic Study* ensures accuracy, especially for less common species.

In conclusion, spore morphology is a cornerstone of yeast identification, offering a wealth of information through shape, color, and surface features. By combining meticulous observation with the right tools and techniques, even novice microbiologists can differentiate between species with confidence. This approach not only aids in taxonomic classification but also has practical applications in industries like food production, medicine, and biotechnology, where precise identification is critical.

A Beginner's Guide to Purchasing Shroom Spore Syringes Safely

You may want to see also

Molecular Methods: Use PCR or DNA sequencing to confirm spore identity at the genetic level

Yeast spores, particularly those of ascomycetes like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, can be morphologically indistinguishable from other fungal spores, making molecular methods essential for precise identification. PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) and DNA sequencing offer unparalleled accuracy by targeting species-specific genetic markers, ensuring reliable classification even when spores are in dormant or resistant states. These techniques are particularly valuable in industries like food production, biotechnology, and clinical diagnostics, where misidentification can have costly or health-related consequences.

To employ PCR for yeast spore identification, begin by extracting genomic DNA from the spore sample using a kit or protocol optimized for fungal cells, such as the CTAB method. Design primers targeting conserved regions like the Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) or D1/D2 domains of the 26S rRNA gene, which exhibit sufficient variability for species-level discrimination. Amplify the DNA using a thermal cycler with a standard protocol: 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. Analyze the amplicons via gel electrophoresis to confirm successful amplification before proceeding to sequencing.

While PCR provides rapid preliminary identification, DNA sequencing offers definitive confirmation. Sanger sequencing of the amplified region generates a nucleotide sequence that can be compared against databases like GenBank or UNITE using tools such as BLAST. A sequence identity match of ≥98% to a known yeast species is generally accepted for classification. For greater precision, whole-genome sequencing or metagenomic analysis can be employed, though these methods are more resource-intensive and typically reserved for research or complex cases.

Despite their power, molecular methods require careful execution to avoid pitfalls. Contamination with foreign DNA, low-quality templates, or non-specific amplification can yield misleading results. Always include negative controls and replicate samples to ensure reliability. Additionally, database limitations may hinder identification of novel or poorly characterized yeast species, necessitating complementary approaches like microscopy or biochemical assays. When executed correctly, however, PCR and DNA sequencing remain the gold standard for confirming yeast spore identity at the genetic level.

Fixing Weird Walking Spore: Simple Solutions for Healthy Plant Growth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yeast spores, also known as ascospores, are reproductive structures formed by certain yeast species during sexual reproduction. Identifying them is important for distinguishing between yeast species, understanding their life cycles, and assessing their role in fermentation, food production, or infection.

Yeast spores appear as small, oval or round structures often found within a sac-like structure called an ascus. They are typically 1-5 micrometers in size and may be arranged in a specific pattern (e.g., 1-8 spores per ascus). Staining techniques like Gram staining or ascospore staining can enhance visibility.

Techniques include microscopic examination after staining, ascospore isolation using spore discharge methods, and molecular methods like PCR or DNA sequencing to identify the species based on genetic markers.

No, not all yeast species produce spores. Only those capable of sexual reproduction, such as *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* and *Schizosaccharomyces pombe*, form spores. Refer to species-specific literature or conduct a sporulation assay to determine if your yeast can produce spores.

Sporulation in yeast typically requires nutrient-limited conditions, such as low nitrogen and high non-fermentable carbon sources. Specific temperature and pH conditions may also be necessary, depending on the species.