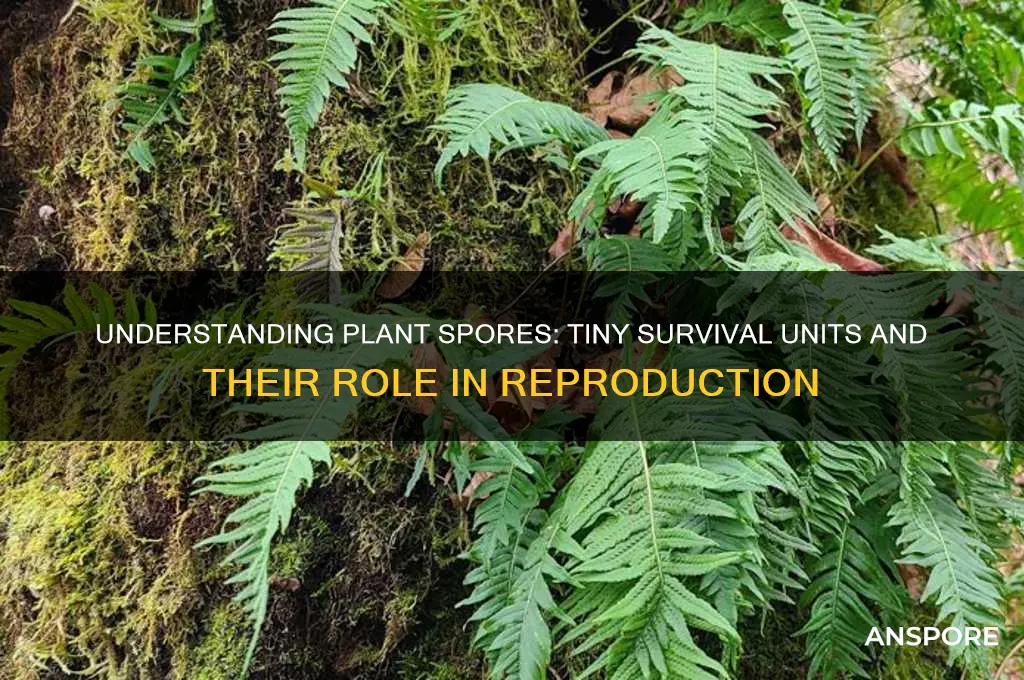

Spores in plants are microscopic, single-celled reproductive units that play a crucial role in the life cycles of many plant species, particularly ferns, mosses, and fungi. Unlike seeds, which contain a developing embryo, spores are simpler structures that can develop into new individuals under favorable conditions. They are typically produced in large quantities and dispersed through wind, water, or animals, allowing plants to colonize new environments efficiently. In plants like ferns, spores are formed in structures called sporangia and undergo a process called alternation of generations, where they grow into a gametophyte stage before producing the next generation. This method of reproduction enables plants to thrive in diverse habitats and ensures their survival in challenging conditions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Spores are microscopic, unicellular or multicellular reproductive units produced by plants, fungi, and some microorganisms. In plants, they are primarily associated with non-seed plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi. |

| Function | Spores serve as a means of asexual reproduction, allowing plants to disperse and colonize new environments. They can also function in sexual reproduction in certain plant groups. |

| Types | Asexual Spores (e.g., gemmae in liverworts) and Sexual Spores (e.g., spores produced via meiosis in ferns and mosses). |

| Size | Typically range from 10 to 50 micrometers in diameter, though sizes vary among species. |

| Structure | Usually consist of a single cell with a protective outer wall, often containing stored nutrients and a nucleus. |

| Dispersal | Dispersed by wind, water, or animals. Some spores have specialized structures (e.g., elaters in hornworts) to aid in dispersal. |

| Dormancy | Many spores can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh conditions until favorable environments trigger germination. |

| Germination | Spores germinate under suitable conditions (e.g., moisture, light) to produce new individuals, such as gametophytes in ferns. |

| Role in Life Cycle | In non-seed plants, spores develop into gametophytes, which produce gametes for sexual reproduction. In fungi, spores grow into new fungal structures. |

| Environmental Adaptation | Spores are highly resistant to desiccation, extreme temperatures, and other environmental stresses, making them effective survival structures. |

| Examples | Fern spores, moss spores, fungal spores (e.g., from mushrooms), and algal spores. |

Explore related products

$24.95 $19.99

$23.29 $24.99

What You'll Learn

- Spores vs. Seeds: Key differences in structure, function, and reproductive strategies in plants

- Types of Spores: Classification into microspores, megaspores, and their roles in plant reproduction

- Spore Formation: Process of sporogenesis in plants, including meiosis and sporangium development

- Spore Dispersal: Mechanisms like wind, water, and animals aiding spore spread in plants

- Spore Germination: Conditions and steps required for spores to develop into gametophytes

Spores vs. Seeds: Key differences in structure, function, and reproductive strategies in plants

Plants employ two primary methods of reproduction: spores and seeds. While both serve the ultimate purpose of perpetuating the species, they differ fundamentally in structure, function, and the strategies they employ. Spores, typically single-celled and microscopic, are produced by plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi. They are lightweight, often dispersed by wind or water, and require moisture to germinate. Seeds, on the other hand, are multicellular structures found in flowering plants (angiosperms) and gymnosperms like conifers. They contain an embryo, stored food, and protective layers, enabling them to survive harsh conditions and germinate when resources are available.

Structurally, spores are simpler and more fragile. They lack the protective coat and nutrient reserves of seeds, making them dependent on immediate favorable conditions for growth. For instance, fern spores must land in a damp, shaded environment to develop into a gametophyte, which then produces reproductive organs. Seeds, however, are designed for resilience. A sunflower seed, for example, can remain dormant in dry soil for months, only sprouting when water and warmth signal optimal conditions. This difference highlights how spores prioritize rapid dispersal and immediate reproduction, while seeds invest in long-term survival and delayed growth.

Functionally, spores and seeds reflect distinct reproductive strategies. Spores are part of an alternation of generations, where the plant alternates between a haploid gametophyte and a diploid sporophyte phase. This cycle allows for genetic diversity through sexual reproduction in the gametophyte stage. Seeds, however, bypass this complexity. They develop directly from the fertilized ovule of the parent plant, ensuring the offspring inherits traits from both parents. This direct approach reduces reliance on external conditions for fertilization, making seeds more efficient in stable environments.

Consider the practical implications for gardeners and ecologists. If you’re cultivating ferns, ensure the soil remains consistently moist to support spore germination. For seed-bearing plants, focus on providing the right balance of light, water, and nutrients during germination. Understanding these differences can also aid in conservation efforts. Spores’ reliance on specific habitats makes spore-producing plants more vulnerable to environmental changes, while seeds’ adaptability allows seed-bearing species to thrive in diverse ecosystems.

In summary, spores and seeds represent contrasting approaches to plant reproduction. Spores excel in simplicity and rapid dispersal, suited for environments where moisture is abundant. Seeds, with their complexity and resilience, dominate in varied and unpredictable habitats. By recognizing these differences, we can better appreciate the diversity of plant life and tailor our care and conservation efforts accordingly. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or nature enthusiast, understanding spores and seeds unlocks deeper insights into the strategies plants use to survive and thrive.

Shroomish's Spore Move: When and How to Unlock It

You may want to see also

Types of Spores: Classification into microspores, megaspores, and their roles in plant reproduction

Spores are the microscopic units of reproduction in plants, fungi, and some other organisms, serving as a means to disperse and survive in diverse environments. Among plants, spores play a critical role in the life cycle, particularly in seedless vascular plants like ferns and in the reproductive processes of seed plants. Within the plant kingdom, spores are classified primarily into microspores and megaspores, each with distinct roles in reproduction. Understanding these types and their functions provides insight into the intricate mechanisms of plant life.

Microspores are smaller spores produced in the male parts of plants, typically within structures like anthers in flowering plants or microsporangia in ferns. In seed plants, microspores develop into pollen grains, which are essential for fertilization. Each microspore contains a haploid nucleus, meaning it carries half the genetic material of the parent plant. Upon maturation, microspores are released and dispersed, often by wind or animals, to reach the female reproductive structures. For example, in angiosperms, pollen grains germinate on the stigma of a flower, grow down the style, and fertilize the ovule, leading to seed formation. This process highlights the microspore’s role as a male gametophyte, initiating the next generation of the plant.

In contrast, megaspores are larger spores produced in the female parts of plants, such as the ovules of seed plants or the megasporangia of ferns. Megaspores are also haploid but are fewer in number and remain within the parent plant’s tissues. In seed plants, one megaspore typically develops into the female gametophyte, which contains the egg cell. This gametophyte is crucial for fertilization, as it provides the environment for the fusion of the male and female gametes. For instance, in angiosperms, the megaspore undergoes mitosis to form the embryo sac, where double fertilization occurs, resulting in the formation of the seed and endosperm. This process underscores the megaspore’s role in nurturing and sustaining the developing embryo.

The distinction between microspores and megaspores is not merely one of size but also of function and destiny. Microspores are prolific and mobile, adapted for dispersal and fertilization, while megaspores are fewer and more protected, focusing on the development of the next generation. This division of labor ensures genetic diversity and the continuity of plant species. For gardeners and botanists, understanding these roles can inform practices like pollination management, seed collection, and plant breeding. For example, knowing the wind-dispersed nature of microspores can guide the placement of plants to optimize pollination, while awareness of megaspore development can aid in seed viability assessments.

In summary, the classification of spores into microspores and megaspores reveals a sophisticated system of plant reproduction. Microspores, as male gametophytes, are dispersed to initiate fertilization, while megaspores, as female gametophytes, nurture the developing embryo. Together, they ensure the survival and diversity of plant species, offering practical insights for horticulture and conservation efforts. By appreciating these roles, we gain a deeper understanding of the natural world and the mechanisms that sustain it.

Lysol's Effectiveness: Can It Eliminate Ringworm Spores Effectively?

You may want to see also

Spore Formation: Process of sporogenesis in plants, including meiosis and sporangium development

Spores are the microscopic, dormant units through which many plants reproduce, serving as a survival mechanism in harsh conditions. Understanding spore formation—or sporogenesis—is key to grasping how plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi perpetuate their species. This process involves meiosis, a specialized cell division, and the development of sporangia, the structures where spores mature. Let’s dissect this intricate process step by step.

Step 1: Meiosis Initiates Spore Formation

Sporogenesis begins with meiosis, a reductive cell division occurring in spore mother cells within the sporangium. Unlike mitosis, which produces genetically identical cells, meiosis halves the chromosome number, creating genetically diverse spores. This diversity is crucial for adaptation in changing environments. For example, in ferns, a single spore mother cell undergoes meiosis to produce four haploid spores, each capable of developing into a new plant under favorable conditions.

Step 2: Sporangium Development and Maturation

The sporangium, a sac-like structure, plays a pivotal role in spore formation. It develops on specialized plant parts, such as the undersides of fern fronds or the tips of moss stems. As the sporangium matures, it becomes a protective chamber where spores grow. In fungi, sporangia often burst open to release spores, while in plants like ferns, they rely on dehydration-induced mechanisms to disperse spores. Proper sporangium development ensures spores are shielded until they are ready for release.

Cautions in Observing Sporogenesis

Studying sporogenesis requires precision. For instance, the sporangia of mosses are tiny (often <1 mm), necessitating magnification tools like microscopes. Additionally, environmental factors like humidity and temperature influence sporangium development. For classroom experiments, maintain a controlled environment (e.g., 25°C and 60% humidity) to observe sporogenesis in real time. Avoid disturbing the sporangia prematurely, as this can disrupt spore maturation.

Practical Takeaway: Harnessing Sporogenesis

Understanding sporogenesis has practical applications, especially in horticulture and conservation. For example, orchid growers use spore cultivation techniques to propagate rare species. By mimicking natural conditions—such as providing sterile substrates and controlled light—growers can induce spore germination. Similarly, conservationists use spore banking to preserve endangered plant species, storing spores in low-temperature environments (e.g., -20°C) for future reintroduction.

In essence, sporogenesis is a marvel of plant biology, blending meiosis and sporangium development to ensure species survival. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or enthusiast, grasping this process unlocks new ways to appreciate and utilize the resilience of spore-producing plants.

Unveiling the Survival Secrets: How Spores Work and Thrive

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$13.99 $17.99

Spore Dispersal: Mechanisms like wind, water, and animals aiding spore spread in plants

Spores are microscopic, lightweight structures produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, serving as a means of reproduction and dispersal. In plants, spores are typically associated with ferns, mosses, and fungi, playing a crucial role in their life cycles. To ensure the survival and propagation of their species, plants have evolved ingenious mechanisms for spore dispersal, harnessing the power of wind, water, and animals.

The Wind's Whisper: A Gentle Nudge for Spores

Wind dispersal is a common and efficient method employed by many spore-producing plants. Ferns, for instance, release spores from the undersides of their leaves, which are then carried away by the slightest breeze. This mechanism is particularly effective due to the spores' minuscule size and lightweight nature. As wind currents rise and fall, they create a turbulent flow that lifts and transports spores over considerable distances. Imagine a summer meadow filled with delicate fern fronds; each spore release is a silent, aerial journey, potentially reaching new habitats and colonizing distant areas. This natural process highlights the importance of wind as a dispersal agent, especially in open environments where air movement is unimpeded.

Aqua Adventure: Spores' Aquatic Journey

Water, too, plays a significant role in spore dispersal, particularly in aquatic or moist environments. Mosses and certain liverworts release their spores near water bodies, relying on currents to carry them away. This strategy is especially advantageous in dense forests or shaded areas where wind dispersal might be less effective. As raindrops fall or streams flow, they dislodge spores from their parent plants, initiating a watery voyage. These spores, often equipped with hydrophobic coatings, float on the water's surface, traveling downstream until they encounter a suitable substrate for germination. This method ensures that spores reach new territories, even in the absence of strong winds.

Animal Allies: Unintentional Couriers of Spores

In a fascinating twist, animals become unwitting partners in spore dispersal. This mechanism is particularly prevalent in fungi, where spores attach themselves to passing creatures. As animals move through spore-rich environments, the microscopic particles adhere to their fur, feathers, or skin. A classic example is the common mushroom, whose spores are dispersed by insects, slugs, and even small mammals. These animals, in their daily activities, transport spores to new locations, facilitating the fungi's colonization of diverse habitats. This symbiotic relationship showcases the ingenuity of nature, where one species' movement inadvertently aids another's propagation.

Strategic Dispersal: A Survival Tactic

The various spore dispersal mechanisms are not random but rather strategic adaptations. Wind dispersal, for instance, is favored by plants in open areas, ensuring wide-reaching distribution. Water dispersal is ideal for plants near rivers or in humid environments, utilizing natural water flow. Animal-aided dispersal, on the other hand, provides a targeted approach, especially for fungi seeking specific habitats. These methods collectively enhance the chances of spore survival and colonization, demonstrating the remarkable ways plants and fungi have evolved to thrive and reproduce in diverse ecosystems. Understanding these processes offers valuable insights into the intricate relationships between organisms and their environments.

Understanding Mold Spore Size: Invisible Threats and Their Impact

You may want to see also

Spore Germination: Conditions and steps required for spores to develop into gametophytes

Spores, the microscopic units of plant reproduction, hold the potential to develop into gametophytes under the right conditions. This process, known as spore germination, is a delicate dance of environmental cues and intrinsic factors. For successful germination, spores require a combination of specific conditions, including adequate moisture, optimal temperature, and sufficient light. In the case of ferns, for instance, spores germinate best in humid environments with temperatures ranging from 20°C to 25°C (68°F to 77°F). Moisture is particularly critical, as it triggers the spore's metabolism and initiates growth.

The steps involved in spore germination are intricate and sequential. First, the spore absorbs water, causing it to swell and rupture its protective outer layer. This process, known as imbibition, is essential for activating the spore's internal enzymes. Next, the spore undergoes cell division, forming a small cluster of cells called a prothallus. In ferns, this prothallus is a heart-shaped structure that develops archegonia (female reproductive organs) and antheridia (male reproductive organs). The prothallus must be kept consistently moist during this stage, as dehydration can halt development.

Environmental factors play a pivotal role in guiding spore germination. Light, for example, can influence the direction and rate of growth. Some spores, like those of mosses, require specific light wavelengths to trigger germination. Red light, in particular, has been shown to stimulate spore germination in certain species. Conversely, excessive light or exposure to UV radiation can inhibit germination, underscoring the need for controlled conditions. For hobbyists or researchers cultivating spores, using grow lights with adjustable spectra can help optimize these conditions.

Practical tips for facilitating spore germination include preparing a sterile substrate, such as a mixture of peat moss and perlite, to prevent contamination. Spores should be evenly distributed on the surface and lightly pressed into the medium to ensure contact. Covering the container with a clear lid or plastic wrap helps maintain humidity, but it’s crucial to ventilate periodically to prevent mold growth. Regular monitoring of temperature and moisture levels is essential, as fluctuations can disrupt germination. For example, using a hygrometer to measure humidity and adjusting it to 80-90% can significantly improve success rates.

In conclusion, spore germination is a precise process requiring careful attention to environmental conditions and developmental stages. By understanding the specific needs of different plant species and implementing practical techniques, one can effectively guide spores through their transformation into gametophytes. Whether for botanical research or gardening, mastering these conditions opens the door to appreciating the remarkable resilience and adaptability of plant life.

Unbelievable Lifespan: How Long Can Spores Survive in Extreme Conditions?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores in plants are microscopic, single-celled reproductive units produced by plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi. They are used for asexual or sexual reproduction and can develop into new plants under favorable conditions.

Plants produce spores through a process called sporogenesis, which occurs in specialized structures like sporangia. In ferns, for example, sporangia are found on the undersides of leaves, while in mosses, they develop on stalk-like structures called sporophytes.

Seeds are produced by flowering plants (angiosperms) and gymnosperms and contain an embryo, stored food, and a protective coat. Spores, on the other hand, are simpler, single-celled structures produced by non-seed plants like ferns and mosses, and they do not contain an embryo or stored food.

Spores are crucial for plant survival because they are lightweight, easily dispersed by wind or water, and can remain dormant for long periods until conditions are suitable for growth. This adaptability allows plants to colonize new environments and survive harsh conditions.