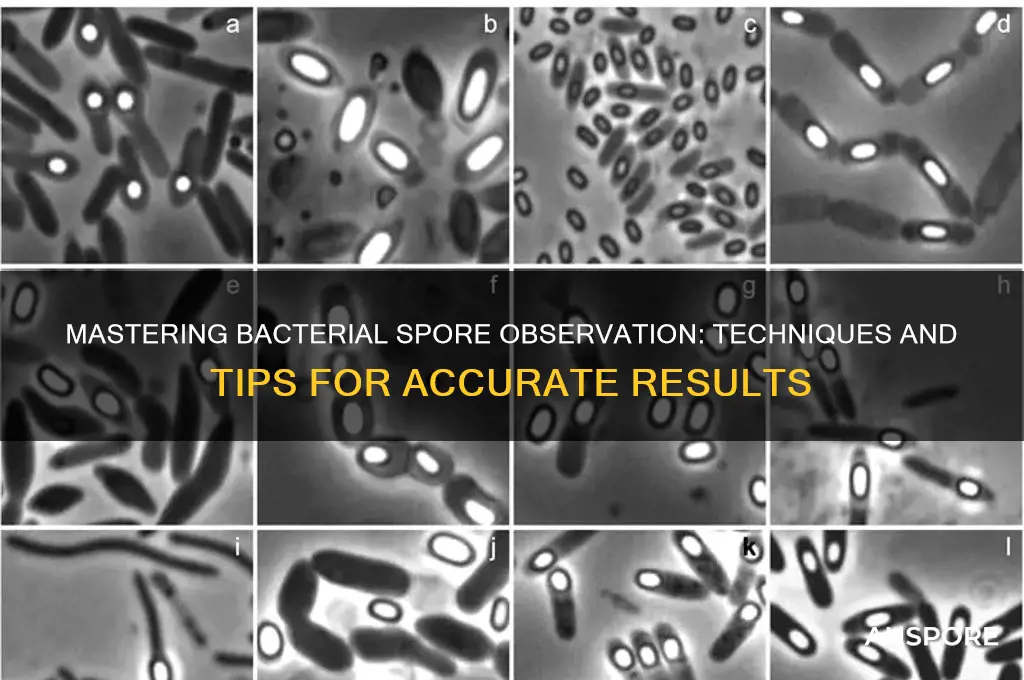

Observing bacterial spores requires careful preparation and the use of specific techniques to visualize these highly resistant structures. Bacterial spores, formed by certain species such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are dormant, resilient forms that can survive extreme conditions. To observe them, one typically begins by preparing a bacterial culture in a nutrient-rich medium under sporulation-inducing conditions, such as nutrient depletion or heat stress. Once spores are formed, they can be stained using specialized techniques like the Schaeffer-Fulton or Dorner methods, which employ heat and dyes such as malachite green to differentiate spores from vegetative cells. Microscopic examination under brightfield or phase-contrast microscopy allows for the identification of spores, which appear as refractile, oval bodies within or outside the bacterial cells. Proper controls and sterile techniques are essential to ensure accurate observation and avoid contamination.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Staining Method | Endospore staining (e.g., Schaeffer-Fulton method) |

| Stain Used | Malachite green (primary stain), Safranin (counterstain) |

| Heat Fixation | Required (e.g., 80°C for 1-2 minutes) |

| Spore Appearance | Green, refractile, oval or round structures within vegetative cells (which appear pink/red) |

| Magnification | 1000X (oil immersion) |

| Spore Size | Typically 0.5-1.5 μm in diameter |

| Refractility | High (appear as bright, refractile bodies under phase-contrast microscopy) |

| Location in Cell | Central or terminal within the bacterial cell |

| Resistance to Staining | Spores resist decolorization due to their impermeable outer layer |

| Common Bacteria with Spores | Bacillus spp., Clostridium spp., Sporosarcina spp. |

| Alternative Methods | Phase-contrast microscopy, fluorescence microscopy with DPA (dipicolinic acid) staining |

| DPA Detection | Spores contain high levels of DPA, detectable via fluorescent dyes like TB (thioflavin T) |

| Viability Testing | Spores are metabolically inactive but germinate under favorable conditions |

| Environmental Resistance | Highly resistant to heat, desiccation, chemicals, and radiation |

| Germination Time | Varies by species (e.g., Bacillus spores germinate within hours under optimal conditions) |

What You'll Learn

- Sample Preparation Techniques: Methods for preparing bacterial samples to ensure clear spore observation under microscopy

- Staining Procedures: Specific stains like Schaeffer-Fulton to differentiate spores from vegetative cells

- Microscopy Settings: Optimal magnification and lighting adjustments for visualizing bacterial spores effectively

- Environmental Conditions: Controlling temperature, humidity, and media to induce spore formation in cultures

- Documentation Methods: Techniques for capturing and recording spore images for analysis and reporting

Sample Preparation Techniques: Methods for preparing bacterial samples to ensure clear spore observation under microscopy

Effective spore observation begins with meticulous sample preparation, a critical step often overlooked in microbial studies. Bacterial spores, renowned for their resilience, require specific techniques to ensure clarity under microscopy. The process involves not only isolating the spores but also preserving their structural integrity while enhancing contrast for visualization. Without proper preparation, spores may appear indistinct, clustered, or damaged, rendering analysis futile. Thus, mastering these methods is essential for accurate and reproducible results.

One widely adopted technique is the heat shock method, which exploits the spores' heat resistance to separate them from vegetative cells. By suspending the bacterial sample in a buffered solution (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline) and heating it to 80°C for 10–15 minutes, vegetative cells are inactivated, while spores remain viable. This step is followed by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 10 minutes to pellet the spores, which are then washed twice to remove debris. The final suspension, when stained with malachite green or safranin, provides a clear contrast against the spores' thick exosporium, facilitating detailed observation under bright-field microscopy.

Alternatively, the sonication method offers a gentler approach for spore extraction, particularly useful for heat-sensitive samples. Here, the bacterial suspension is subjected to ultrasonic waves (20–30 kHz) for 5–10 minutes, disrupting cell walls and releasing spores without compromising their structure. This technique, combined with density gradient centrifugation using solutions like Nycodenz (40% w/v), allows for precise separation of spores from cellular debris. The purified spores can then be mounted on a slide with a mounting medium like glycerol, ensuring they remain immobilized and evenly distributed for high-resolution imaging.

For advanced applications, such as electron microscopy, critical point drying (CPD) is indispensable. This technique involves fixing the spore sample in glutaraldehyde (2.5% in cacodylate buffer), followed by dehydration in a graded ethanol series (30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, and 100%). The sample is then transferred to a CPD chamber, where it is dried under high pressure with liquid carbon dioxide, preserving the spores' three-dimensional structure. The dried sample, coated with a thin layer of gold or platinum, reveals intricate surface details under scanning electron microscopy, offering insights into spore morphology and architecture.

In conclusion, the choice of sample preparation technique depends on the observational goal and the spore's characteristics. While heat shock and sonication cater to light microscopy, CPD is tailored for electron microscopy. Each method demands precision and adherence to protocol to ensure clarity and accuracy in spore observation. By selecting the appropriate technique, researchers can unlock the microscopic world of bacterial spores, advancing our understanding of their biology and applications.

Beyond Fungi: Exploring the Diverse World of Spore-Producing Organisms

You may want to see also

Staining Procedures: Specific stains like Schaeffer-Fulton to differentiate spores from vegetative cells

Bacterial spores, with their resilient nature, often require specialized techniques for visualization. One such method is the Schaeffer-Fulton stain, a differential staining procedure that effectively distinguishes spores from vegetative cells. This technique leverages the spores' resistance to decolorization, allowing them to retain the primary stain while the vegetative cells are decolorized.

The Staining Process

To perform the Schaeffer-Fulton stain, begin by preparing a bacterial smear on a clean glass slide. Heat-fix the smear to adhere the cells to the slide, ensuring they remain intact during the staining process. Next, flood the slide with malachite green, the primary stain, and gently heat the slide to facilitate dye penetration into the spores. Allow the slide to cool, then rinse it with water to remove excess stain. Decolorize the slide using a mixture of 95% ethanol and 0.5% hydrochloric acid, taking care not to over-decolorize, as this may affect the spores' staining. Counterstain the slide with safranin to impart a pink color to the vegetative cells, providing a clear contrast against the green spores.

Key Considerations

When performing the Schaeffer-Fulton stain, it is essential to maintain proper timing and temperature control. Overheating the slide during the primary staining step can cause the spores to become overstained, while insufficient heating may result in inadequate dye penetration. Similarly, over-decolorization can lead to the loss of spore staining, whereas under-decolorization may leave vegetative cells stained with malachite green. To optimize results, use a water bath or a slide warmer to maintain a consistent temperature during the staining process.

Comparative Advantages

Compared to other staining techniques, such as the endospore stain, the Schaeffer-Fulton method offers several advantages. Its use of malachite green as the primary stain provides a more intense and durable color, making it easier to distinguish spores from vegetative cells. Additionally, the counterstaining step with safranin enhances the contrast between the two cell types, facilitating more accurate identification. This method is particularly useful for studying spore-forming bacteria, such as Bacillus and Clostridium species, in various fields, including microbiology, food science, and environmental monitoring.

Practical Applications and Tips

In practical applications, the Schaeffer-Fulton stain can be used to assess the efficacy of sterilization processes, detect spore-forming contaminants in food and water samples, and study the development and germination of bacterial spores. To ensure consistent results, prepare fresh staining solutions for each use, as prolonged storage can lead to degradation of the dyes. When working with potentially hazardous bacteria, follow proper laboratory safety protocols, including the use of personal protective equipment and sterile techniques. By mastering the Schaeffer-Fulton staining procedure, researchers and laboratory professionals can gain valuable insights into the world of bacterial spores, informing their work in various scientific and industrial contexts.

Spore Formation: A Key Mechanism Boosting Microbial Pathogenicity

You may want to see also

Microscopy Settings: Optimal magnification and lighting adjustments for visualizing bacterial spores effectively

Bacterial spores, with their resilient nature and compact structure, demand precise microscopy settings for clear visualization. The optimal magnification range typically falls between 1000x and 10,000x, depending on the spore size and the microscope’s capabilities. Lower magnifications may fail to reveal spore-specific features like the exosporium or spore coat, while excessively high magnifications can introduce distortion or reduce the field of view unnecessarily. For most standard light microscopes, a 100x oil immersion objective paired with a 10x eyepiece provides a practical starting point, offering a balance between detail and clarity.

Lighting adjustments are equally critical, as bacterial spores often exhibit subtle contrasts that require enhancement. Phase-contrast microscopy is highly effective for this purpose, as it converts phase shifts in light passing through the spore into visible differences in brightness. This technique highlights the spore’s internal structures without the need for staining, preserving the sample’s integrity. Alternatively, differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy can be employed to create a pseudo-3D image, emphasizing the spore’s surface topography and making it easier to distinguish from the surrounding medium. Both methods rely on precise alignment of the microscope’s condenser and light source, so ensure the condenser aperture is fully open and the light intensity is adjusted to maximize contrast.

For stained samples, such as those treated with malachite green or safranin, brightfield microscopy with careful lighting control is sufficient. Here, the key is to avoid overexposure, which can wash out the stain’s color and obscure details. Use a 50-70% light intensity setting and a neutral density filter if available to reduce glare. When working with fluorescently labeled spores, switch to fluorescence microscopy, ensuring the excitation wavelength matches the fluorophore’s absorption spectrum. For example, DAPI-stained spores require a UV light source (350-400 nm), while GFP-labeled spores need blue light (450-490 nm). Adjust the emission filter to capture only the fluorescent signal, minimizing background noise.

Practical tips can further enhance spore visualization. Always use a high-quality immersion oil with a refractive index matching the microscope’s objective (typically 1.518) to minimize spherical aberration. Clean the slide and coverslip thoroughly to eliminate debris that could mimic spores under high magnification. For live samples, maintain a stable temperature using a microscope stage incubator, as temperature fluctuations can alter spore morphology. Finally, capture multiple focal planes using z-stack imaging to reconstruct a complete 3D profile of the spore, particularly useful for thick samples or clustered spores.

In summary, effective visualization of bacterial spores hinges on a combination of magnification, lighting technique, and practical considerations. By selecting the appropriate magnification range, optimizing lighting for contrast, and employing specific microscopy modes tailored to the sample type, researchers can reveal the intricate details of these resilient structures. Attention to detail in setup and technique ensures that the observed features are accurately represented, facilitating both qualitative and quantitative analysis.

Can Alcohol Effectively Eliminate Mold Spores? Facts and Myths Revealed

You may want to see also

Environmental Conditions: Controlling temperature, humidity, and media to induce spore formation in cultures

Bacterial spores are a resilient survival mechanism, but their formation isn't spontaneous. To observe them, you need to recreate the environmental pressures that trigger this response. Think of it as coaxing a seed to germinate – specific conditions are required for success.

The Temperature Trigger: Temperature acts as a primary signal for spore formation. Many spore-forming bacteria, like *Bacillus subtilis*, initiate sporulation when faced with nutrient depletion and a temperature shift. A common protocol involves cultivating the bacteria at their optimal growth temperature (around 37°C for many species) until late exponential phase, then shifting to a lower temperature, typically 25-30°C. This mimics the natural transition from a nutrient-rich to a nutrient-limited environment, prompting the cells to enter a dormant state.

Precision is key. Use a temperature-controlled incubator and monitor the culture closely. A sudden, drastic temperature drop can shock the cells, while a gradual shift allows for a more natural response.

Humidity's Role: While less directly influential than temperature, humidity plays a supporting role. Spores are designed to withstand desiccation, but the initial stages of sporulation are sensitive to moisture levels. Maintaining a humid environment (around 70-80% relative humidity) during the temperature shift can enhance spore yield. This can be achieved by using a humidified incubator or placing a water reservoir within the growth chamber.

Think of it as providing a buffer zone – enough moisture to support the initial stages of sporulation, but not so much that it hinders the drying process necessary for mature spore formation.

Media Manipulation: The composition of the growth medium is crucial. Nutrient depletion is a key trigger for sporulation. As the bacteria exhaust readily available nutrients, they sense starvation and initiate the sporulation pathway. To induce spore formation, gradually reduce the nutrient concentration in the media. This can be done by serially diluting the culture into fresh, nutrient-limited media or by using defined media specifically formulated to promote sporulation.

The Art of Observation: Once you've manipulated the environment to encourage spore formation, observing them requires specific techniques. Microscopy is the primary tool. Phase-contrast microscopy allows you to visualize the characteristic oval shape and refractile nature of spores. For more detailed analysis, staining techniques like the Schaeffer-Fulton stain can differentiate spores from vegetative cells.

Remember, inducing spore formation is a delicate balance. Too harsh conditions can kill the cells, while too gentle conditions may not trigger the sporulation pathway. Careful control of temperature, humidity, and media composition, combined with patient observation, will reward you with the fascinating sight of bacterial spores, nature's tiny survival capsules.

Can TB Spores Float in the Air? Understanding Tuberculosis Transmission

You may want to see also

Documentation Methods: Techniques for capturing and recording spore images for analysis and reporting

Effective documentation of bacterial spores hinges on clarity, precision, and reproducibility. High-resolution microscopy is the cornerstone of this process, with phase-contrast and differential interference contrast (DIC) techniques offering superior contrast for spore visualization without staining. For instance, DIC microscopy enhances the three-dimensional structure of spores, revealing surface details critical for identification. Pairing these methods with digital cameras capable of capturing at least 12-megapixel images ensures data integrity for subsequent analysis.

The choice of staining technique significantly impacts image quality and analytical utility. Endospore-specific stains like Schaeffer-Fulton or Dorner’s method employ malachite green and safranin to differentiate spores from vegetative cells. While these methods are reliable, they require heat fixation, which may alter spore morphology. For live-cell imaging, fluorescent dyes such as DAPI or SYTO 9 can be used, but their application must be carefully calibrated—typically 1-2 μL of a 1:1000 dilution per slide—to avoid phototoxicity or background noise.

Post-capture processing is where raw data transforms into actionable insights. Software like ImageJ or Adobe Photoshop enables adjustments to brightness, contrast, and color balance, but alterations must be documented to maintain transparency. For quantitative analysis, automated tools can measure spore size, shape, and density, though manual verification is recommended for accuracy. Reporting should adhere to standardized formats, including metadata such as magnification, staining protocol, and environmental conditions, ensuring replicability across studies.

Archiving and sharing spore images demand robust systems to preserve both visual data and associated metadata. Cloud-based platforms like Figshare or institutional repositories offer long-term storage solutions, while open-access journals require compliance with FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles. When exporting files, use lossless formats like TIFF or PNG to retain image fidelity, and embed metadata directly into files using tools like ExifTool to prevent information loss during transfer.

Finally, ethical considerations cannot be overlooked in spore documentation. Images used for publication or training must respect intellectual property rights, with proper attribution and permissions secured. For clinical or environmental samples, anonymization protocols should be applied to protect patient or location confidentiality. By integrating technical rigor with ethical mindfulness, researchers ensure that spore documentation serves as a reliable foundation for scientific advancement.

Assessing Bacillus Subtilis Spores Viability: A Comprehensive Testing Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The best methods include staining techniques such as the Schaeffer-Fulton stain or the Moeller stain, which differentiate spores from vegetative cells. Spores appear as refractile, green, or red bodies depending on the stain used. Phase-contrast or bright-field microscopy can also be employed to visualize spores without staining, though staining enhances clarity.

Yes, bacterial spores can be observed without staining using phase-contrast microscopy or dark-field microscopy. Spores appear as bright, refractile bodies due to their high refractive index compared to the surrounding cell material. However, staining provides better contrast and detail for identification.

Always work in a biosafety cabinet or fume hood to prevent spore aerosolization. Wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), including lab coats, gloves, and safety goggles. Heat-fix slides before staining to kill spores and prevent contamination. Properly dispose of all materials and decontaminate surfaces after use.