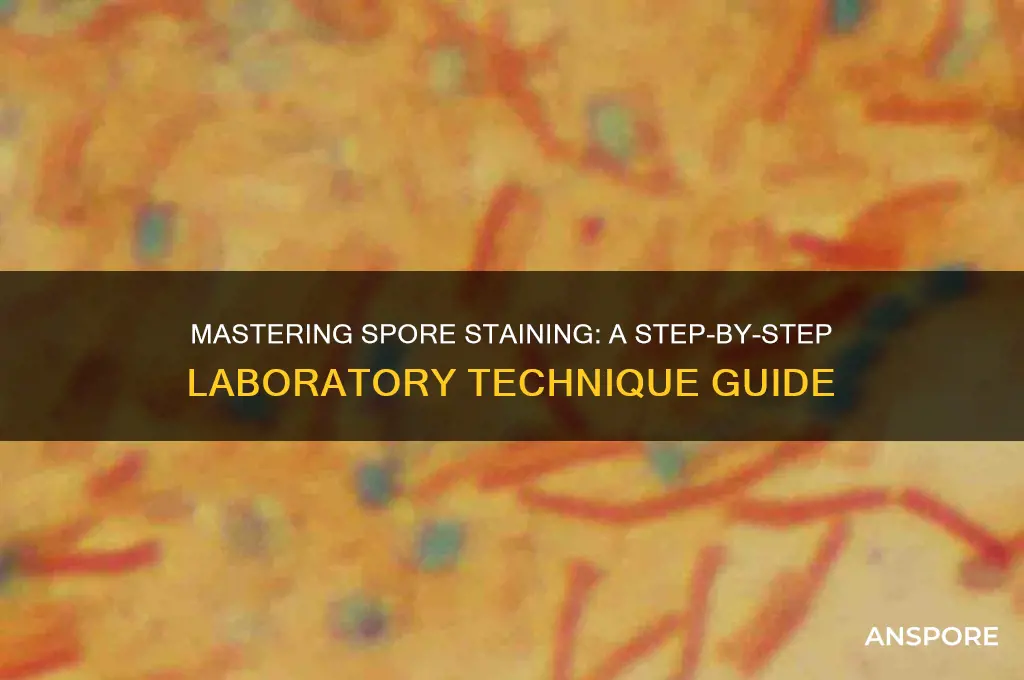

Spore staining is a specialized microbiological technique used to differentiate bacterial spores from vegetative cells, leveraging their unique resistance to heat, chemicals, and dyes. Unlike vegetative cells, spores possess a thick, impermeable outer layer that requires a more rigorous staining process. The most common method, the Schaeffer-Fulton technique, involves heat fixation, primary staining with malachite green, and counterstaining with safranin. The heat treatment helps drive the malachite green into the spore’s durable coat, staining it green, while the vegetative cells and background are stained red by safranin. This contrast allows for clear visualization of spores under a microscope, making spore staining an essential tool in identifying spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species, in clinical, environmental, and industrial samples.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Purpose | To visualize and differentiate bacterial spores from vegetative cells |

| Principle | Spores are highly resistant to heat, chemicals, and dyes, allowing them to survive the staining process while vegetative cells are stained |

| Staining Technique | Differential staining (uses two dyes: a primary dye and a counterstain) |

| Primary Dye | Malachite green (applied with heat to force dye into spores) |

| Counterstain | Safranin (stains vegetative cells and background) |

| Heat Fixation | Required to adhere cells to slide and enhance spore staining |

| Heat Application | Steam or gentle heat (e.g., over a water bath) for 3-5 minutes during malachite green application |

| Decolorization | Not typically required, as spores retain malachite green while vegetative cells take up safranin |

| Spore Appearance | Green, refractile, and oval or round under microscope |

| Vegetative Cell Appearance | Pink or red under microscope |

| Common Applications | Identifying spore-forming bacteria (e.g., Bacillus, Clostridium) in clinical, environmental, or food samples |

| Safety Precautions | Handle bacterial cultures with care; use appropriate PPE (gloves, lab coat, goggles) |

| Limitations | Does not differentiate between spore-forming species; requires additional tests for identification |

| Advantages | Simple, cost-effective, and rapid method for spore detection |

| Disadvantages | Subjective interpretation; requires skilled microscopist |

| Quality Control | Use known spore-forming and non-spore-forming controls for validation |

What You'll Learn

- Sample Preparation: Properly prepare the sample by fixing it to a slide for staining

- Heat Fixation: Apply heat to adhere organisms firmly to the slide surface

- Primary Stain: Apply the primary stain (e.g., Malachite Green) to color spores

- Decolorization: Use a decolorizer (e.g., alcohol) to remove excess primary stain

- Counterstain: Apply a counterstain (e.g., Safranin) to color vegetative cells

Sample Preparation: Properly prepare the sample by fixing it to a slide for staining

Effective spore staining begins with meticulous sample preparation, as the integrity of your results hinges on how well the sample adheres to the slide. Fixation is the cornerstone of this process, ensuring that spores remain securely attached and properly oriented for staining. Without adequate fixation, spores may detach during subsequent steps, leading to inconsistent or unreliable results. This stage demands precision and attention to detail, as even minor errors can compromise the entire procedure.

To fix your sample, start by placing a small drop of water or a suitable fixative, such as formaldehyde or methanol, onto a clean microscope slide. The choice of fixative depends on the spore type and the specific staining protocol you’re following. For most bacterial endospores, a simple heat fixation method is often sufficient. Briefly pass the slide through a flame 2–3 times using a bunsen burner, ensuring the slide is evenly heated without overheating. This process kills the organisms and adheres them firmly to the slide surface. Alternatively, for more delicate samples, chemical fixation with 10% formaldehyde for 10 minutes followed by gentle washing with distilled water can be employed.

A critical yet often overlooked aspect of sample preparation is the concentration of the spore suspension. Too dense a suspension can lead to overcrowding on the slide, making it difficult to distinguish individual spores during staining. Conversely, a suspension that is too dilute may result in an insufficient number of spores for analysis. Aim for a suspension with a concentration of approximately 10^6 to 10^7 spores per milliliter. This range ensures adequate coverage without overcrowding, allowing for clear visualization under the microscope.

Once fixed, the slide must be air-dried thoroughly before proceeding to the staining step. Residual moisture can interfere with the staining reagents, leading to uneven or incomplete staining. After fixation, allow the slide to air-dry at room temperature for 10–15 minutes. Avoid using external heat sources like a hairdryer, as excessive heat can damage the sample. Proper drying ensures that the spores are ready to interact optimally with the staining solutions, setting the stage for accurate and reproducible results.

In summary, sample preparation is a critical step in spore staining that requires careful attention to fixation, suspension concentration, and drying. By following these guidelines—whether using heat or chemical fixation, optimizing spore concentration, and ensuring thorough drying—you can create a robust foundation for the staining process. Mastery of this stage not only enhances the reliability of your results but also streamlines the overall workflow, making it a cornerstone of successful spore staining.

Do All 370Z Touring Models Include the Sport Package?

You may want to see also

Heat Fixation: Apply heat to adhere organisms firmly to the slide surface

Heat fixation is a critical step in spore staining, serving as the foundation for subsequent procedures by securely anchoring microorganisms to the slide. Without this step, organisms can be washed away during staining, leading to false negatives or inconsistent results. The process involves applying gentle, controlled heat to the slide, typically using a flame or specialized heating device. This denatures cellular proteins and alters the cell wall structure, effectively "gluing" the organisms to the glass surface. For optimal results, ensure the slide is clean and dry before applying a thin, even smear of the sample. Overheating must be avoided, as it can distort cellular morphology or char the specimen, rendering it unsuitable for staining.

The technique of heat fixation varies slightly depending on the equipment available. If using an open flame, such as a Bunsen burner, pass the slide through the flame 2–3 times, ensuring the entire smear is exposed to heat. The slide should be held in a clothespin or crucible tongs to prevent burns. Alternatively, an electric slide warmer or incubator set to 65–70°C for 10–15 minutes can be used, particularly in settings where open flames are impractical. For heat-sensitive organisms, reduce exposure time or temperature to minimize damage. Always observe the slide during fixation; a faint yellowing of the smear indicates adequate heat application, while browning or blackening signals overheating.

Comparing heat fixation to alternative methods, such as chemical fixation with methanol, highlights its advantages and limitations. While chemical fixation is quicker and avoids heat-related artifacts, it may not provide the same level of adherence for spore-forming bacteria, which have robust cell walls. Heat fixation is particularly essential for endospore staining techniques like the Schaeffer-Fulton method, where spores must remain firmly attached during the rigorous decolorization step. However, heat fixation is less suitable for delicate organisms like Rickettsia or Chlamydia, which require gentler methods to preserve morphology.

In practice, mastering heat fixation requires attention to detail and consistency. Beginners often struggle with uneven heating, leading to partial detachment of organisms. To mitigate this, ensure the smear is uniformly thin and spread across the slide. For educational settings, pre-prepared slides can be used to demonstrate the process, allowing students to observe the effects of proper and improper fixation. Advanced users may experiment with different heat sources to determine the most efficient method for their workflow. Ultimately, a well-executed heat fixation step is the cornerstone of reliable spore staining, ensuring accurate and reproducible results.

Does E. Coli Release Airborne Spores? Unraveling the Facts

You may want to see also

Primary Stain: Apply the primary stain (e.g., Malachite Green) to color spores

The primary stain is the cornerstone of spore staining, and Malachite Green is the dye of choice for this critical step. Its deep green color penetrates the tough spore coat, providing a vivid contrast against the lighter background of the vegetative cells. This contrast is essential for accurate identification and enumeration of spores under a microscope. Malachite Green's ability to bind to the spore's heat-resistant coat, even after the intense heat fixation step, makes it the ideal candidate for this procedure.

Applying the primary stain requires precision and attention to detail. Begin by heating the Malachite Green solution to a gentle simmer, typically around 60-70°C. This temperature range ensures the dye's optimal penetration without causing excessive damage to the spore structure. Using a staining rack, carefully suspend the slide containing the heat-fixed smear over the staining jar, allowing the steam to carry the dye onto the specimen. Maintain this position for 5-7 minutes, ensuring even exposure to the stain. The duration of this step is crucial, as insufficient staining may result in faint or uneven coloration, while over-staining can lead to background noise and reduced contrast.

A common challenge in this step is achieving uniform staining across the entire slide. To address this, gently agitate the staining jar or use a staining dish with a built-in platform to ensure consistent exposure. Additionally, consider using a staining timer to monitor the duration accurately. For laboratories processing multiple samples, a staining rack with individual slide holders can help maintain organization and prevent cross-contamination. It's also essential to use high-quality Malachite Green solution, as impurities or degraded dye can compromise the staining results.

In comparative terms, Malachite Green offers several advantages over alternative primary stains. Its high specificity for spores, combined with its resistance to decolorization during the subsequent steps, makes it a reliable choice for both routine and diagnostic applications. While other dyes like Brilliant Green or Methyl Green may be used in specific circumstances, Malachite Green remains the gold standard due to its consistency and ease of use. However, it's crucial to handle this dye with care, as it can be toxic if ingested or inhaled. Always wear appropriate personal protective equipment, such as gloves and a lab coat, and work in a well-ventilated area or fume hood.

To optimize the primary staining step, consider the following practical tips: pre-warm the staining solution to reduce heating time, use a staining jar with a tight-fitting lid to minimize evaporation, and clean the slide surface thoroughly before staining to remove any debris or contaminants. After staining, carefully rinse the slide with distilled water to remove excess dye, taking care not to wash away the stained spores. With practice and attention to detail, the primary staining step can be mastered, providing a solid foundation for the subsequent decolorization and counterstaining stages. By following these guidelines, you'll be well on your way to producing high-quality spore stains that meet the standards of even the most demanding microbiological applications.

Can Alcohol-Based Hand Rubs Effectively Kill Spores? The Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Decolorization: Use a decolorizer (e.g., alcohol) to remove excess primary stain

Decolorization is a critical step in spore staining, serving as the bridge between primary staining and counterstaining. Its purpose is precise: to remove the primary stain from the vegetative cells while leaving the spores stained. This contrast is essential for clear visualization under a microscope. The decolorizer, typically a solution of alcohol (such as 95% ethanol) or acetone, acts by solubilizing the primary stain (often malachite green) from the less resilient cell walls of vegetative cells, while the spores, with their thicker, more impermeable walls, retain the stain. This differential staining ensures that spores stand out distinctly against the unstained or counterstained background.

The process of decolorization requires careful technique to avoid over-decolorizing, which can strip stain from the spores, or under-decolorizing, which leaves vegetative cells stained and obscures the spores. A common method involves gently rinsing the slide with the decolorizer for 30–60 seconds, followed by a brief water rinse to stop the decolorizing action. The timing is crucial: too long, and the spores may lose their stain; too short, and vegetative cells remain stained. For optimal results, use a dropper or wash bottle to apply the decolorizer evenly, ensuring all areas of the smear are treated uniformly.

Comparing decolorizers, alcohol is the most commonly used due to its effectiveness and accessibility. However, acetone can be a stronger alternative for more stubborn stains, though it requires careful handling due to its volatility and flammability. Regardless of the decolorizer chosen, the principle remains the same: it must act quickly and selectively. This step highlights the importance of understanding the properties of both the decolorizer and the microbial structures being stained, as it directly influences the clarity and accuracy of the final result.

A practical tip for beginners is to practice timing and technique on control slides before working with critical samples. Observing the slide under a microscope immediately after decolorization can provide real-time feedback, allowing adjustments to be made in subsequent attempts. Additionally, maintaining a consistent room temperature during the procedure helps ensure reproducibility, as temperature can affect the rate of decolorization. Mastery of this step transforms spore staining from a hit-or-miss process into a reliable, precise technique.

Understanding Fungal Spores: Their Role in Fungus Reproduction and Survival

You may want to see also

Counterstain: Apply a counterstain (e.g., Safranin) to color vegetative cells

After the primary stain has differentiated spores from vegetative cells, the counterstaining step becomes crucial for visualizing the latter. Safranin, a pink-red dye, is commonly employed here due to its affinity for cellular material not already stained by the primary agent. This step ensures that both spore and vegetative cell populations are distinctly visible under microscopy, allowing for accurate identification and enumeration.

Application Technique:

To apply the counterstain, flood the slide with a 0.1% safranin solution, ensuring complete coverage of the smear. Allow the stain to act for 2–5 minutes at room temperature (20–25°C). This duration balances penetration efficiency with minimal background staining. Gently rinse the slide with distilled water to remove excess dye, blotting the edges with filter paper to avoid smudging.

Mechanism and Contrast:

Safranin binds to RNA and proteins in vegetative cells, which remain unstained by the primary agent (e.g., malachite green used for spores). This differential staining creates a stark contrast: spores appear green, while vegetative cells take on a pink-red hue. Such clarity is essential for distinguishing between dormant and metabolically active cells, particularly in samples from soil, water, or clinical specimens.

Practical Considerations:

Over-staining with safranin can obscure spore details, so adhere strictly to the recommended time frame. For heat-fixed smears, ensure the slide is thoroughly dried before staining to prevent dye runoff. If using alternative counterstains (e.g., fuchsine), adjust concentrations and exposure times accordingly, as each dye has unique binding properties.

Troubleshooting Tips:

If vegetative cells appear faint or unevenly stained, verify the safranin solution’s concentration and freshness. Expired or diluted stains may lack efficacy. In cases of excessive background staining, reduce the staining time or perform a brief counter-rinse with 95% ethanol before applying safranin. Proper slide preparation, including even smear thickness, also minimizes artifacts in this step.

By mastering the counterstaining process, technicians can produce slides where both spore and vegetative cells are clearly delineated, facilitating precise microbiological analysis. This step transforms a monochrome image into a dual-toned, informative visual tool, critical for applications ranging from environmental monitoring to diagnostic pathology.

Troubleshooting Spore Code Redemption Issues on Steam: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spore staining is a technique used to differentiate between bacterial spores and vegetative cells. It helps in identifying spore-forming bacteria, such as Bacillus and Clostridium species, by staining the spores a distinct color, typically green or red, while leaving the vegetative cells unstained or stained a different color.

The main steps in spore staining are: 1) Heat fixation of the bacterial smear to adhere cells to the slide, 2) Application of the primary stain (e.g., malachite green) and heating to force the stain into the spores, 3) Decolorization with water to remove the primary stain from vegetative cells, 4) Counterstaining with a contrasting dye (e.g., safranin) to stain the vegetative cells, and 5) Examination under a microscope to observe the stained spores and cells.

Heat application is necessary to drive the malachite green stain into the spore's inner layers, as spores have a tough outer coat that resists staining. Precautions include using a water bath or gentle heat source to avoid overheating, ensuring the slide is heat-fixed properly to prevent detachment of cells, and monitoring the process to avoid over-decolorization or damage to the sample.