Endomycorrhizae spores, which are crucial for the symbiotic relationship between fungi and plant roots, can be observed through a systematic process that combines soil sampling, spore extraction, and microscopic examination. To begin, collect soil samples from the rhizosphere of plants known to host endomycorrhizal fungi, ensuring the samples are free from debris. Next, employ techniques such as wet sieving or centrifugation to separate the spores from soil particles. The extracted spores can then be mounted on a microscope slide, often stained with dyes like trypan blue or ink vinegar to enhance visibility. Using a compound microscope with appropriate magnification (typically 400x or higher), carefully examine the slide to identify the characteristic features of endomycorrhizae spores, such as their size, shape, and surface texture. This method allows researchers and enthusiasts to study these vital fungal structures and their role in plant health and ecosystem dynamics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Microscopy | Light microscopy (LM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) are commonly used to visualize endomycorrhizal spores. LM allows for observation of spore morphology, color, and size, while SEM provides high-resolution images of spore surface structures. |

| Staining Techniques | Spores can be stained with dyes like trypan blue, lactophenol cotton blue, or ink vinegar to enhance contrast and visibility under LM. |

| Soil Sampling | Collect soil samples from the rhizosphere (root zone) of plants known to form endomycorrhizal associations. Samples should be air-dried, sieved, and stored in a cool, dry place. |

| Spore Extraction | Use wet sieving and sucrose density gradient centrifugation to separate spores from soil particles. This process concentrates spores for easier observation. |

| Spore Size | Endomycorrhizal spores typically range from 20 to 500 μm in diameter, depending on the fungal species. |

| Spore Shape | Spores can be globose, subglobose, ellipsoid, or irregular in shape. |

| Spore Color | Colors vary widely, including white, yellow, brown, black, or translucent, depending on the species and maturity. |

| Surface Features | SEM reveals surface details such as ornamentation, ridges, or reticulations, which are species-specific. |

| Germination Tests | Spores can be tested for viability by placing them on a suitable growth medium and observing germination under controlled conditions. |

| Molecular Identification | DNA sequencing (e.g., ITS region) can be used to confirm the identity of endomycorrhizal fungi, complementing morphological observations. |

| Field Identification Guides | Use field guides or atlases specific to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) to match spore characteristics with known species. |

| Environmental Factors | Spore abundance and diversity are influenced by soil type, pH, moisture, and plant host species. |

| Preservation | Spores can be preserved in polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) or other mounting media for long-term storage and reference. |

What You'll Learn

- Sample Collection Methods: Techniques for gathering soil or root samples to isolate endomycorrhizae spores effectively

- Spore Extraction Procedures: Steps to separate spores from soil or root material using sieving or centrifugation

- Microscopic Preparation: How to mount and stain spores for clear visualization under a microscope

- Microscopic Identification: Key features to recognize endomycorrhizae spores, such as size, shape, and color

- Advanced Imaging Techniques: Using fluorescence or electron microscopy for detailed spore structure analysis

Sample Collection Methods: Techniques for gathering soil or root samples to isolate endomycorrhizae spores effectively

Soil and root samples are the gateways to observing endomycorrhizae spores, but their delicate nature demands precise collection techniques. Improper handling can disrupt spore integrity or introduce contaminants, rendering samples useless. Here’s a step-by-step guide to ensure effective isolation.

Step 1: Site Selection and Sampling Depth

Choose sampling locations representative of the habitat, avoiding areas with obvious disturbances like foot traffic or recent tilling. For agricultural fields, collect samples from both high-yield and low-yield zones to compare mycorrhizal activity. Use a soil corer (5–10 cm diameter) to extract samples at depths of 0–15 cm for annual crops and 0–30 cm for perennials, as endomycorrhizae are most abundant in topsoil. For root samples, carefully excavate plants, ensuring the root system remains intact.

Step 2: Sterile Handling and Storage

Contamination is the arch-nemesis of spore isolation. Sterilize all tools (e.g., trowels, corers) with 70% ethanol before use. Place soil samples in airtight, labeled bags, and store root samples in damp paper towels within sealed containers. Keep samples cool (4°C) during transport to preserve spore viability. Avoid freezing, as it can rupture spore walls.

Cautions and Troubleshooting

Over-drying soil samples can reduce spore recovery, while excessive moisture promotes mold growth. If roots are muddy, gently rinse them with sterile water, but avoid scrubbing, as this can dislodge spores. For highly compacted soils, sieve samples through a 2-mm mesh to separate roots and fine soil particles without damaging spores.

Effective sample collection is not just about gathering material—it’s about preserving the microscopic world within. By adhering to these techniques, researchers can ensure that the endomycorrhizae spores they seek remain intact, visible, and ready for analysis. Each step, from site selection to storage, is a link in the chain of discovery, turning soil and roots into windows to the hidden symbiosis beneath our feet.

Effective Strategies to Eliminate OE Spores and Prevent Infections

You may want to see also

Spore Extraction Procedures: Steps to separate spores from soil or root material using sieving or centrifugation

Endomycorrhizae spores, though microscopic, play a pivotal role in soil health and plant nutrition. To observe these spores, they must first be separated from the complex matrix of soil or root material. Two primary methods dominate this process: sieving and centrifugation. Each technique offers distinct advantages and challenges, making them suitable for different laboratory settings and research objectives.

Sieving: A Mechanical Approach

Sieving is a straightforward, cost-effective method for isolating endomycorrhizae spores. Begin by air-drying soil or root samples to loosen the material, then pass it through a series of sieves with decreasing mesh sizes. Start with a coarse sieve (e.g., 2 mm) to remove large debris, followed by finer sieves (e.g., 500 µm and 300 µm) to capture spores. For root material, gently grind the roots before sieving to release spores trapped within tissues. A key advantage of sieving is its simplicity, requiring minimal equipment—just sieves, a brush, and a container. However, this method may not yield high purity, as spores can remain attached to fine soil particles. To enhance results, combine sieving with a density gradient solution (e.g., sucrose or Percoll) to separate spores from lighter organic matter.

Centrifugation: Precision Through Density Separation

Centrifugation offers a more precise alternative, leveraging differences in spore density to isolate them from soil or root extracts. First, suspend the sample in a sterile solution (e.g., water or 50% sucrose) and blend or sonicate to disperse spores. Pour the suspension into centrifuge tubes and spin at controlled speeds (e.g., 1,000–2,000 rpm for 10 minutes) to pellet spores. For finer separation, use a discontinuous density gradient (e.g., 30%, 50%, and 70% sucrose layers) and centrifuge at higher speeds (e.g., 3,000 rpm for 30 minutes). Spores will accumulate at the interface between layers, allowing for easy collection. While centrifugation yields higher purity, it demands specialized equipment and careful optimization of centrifugation parameters to avoid spore damage.

Comparative Analysis: Choosing the Right Method

The choice between sieving and centrifugation hinges on resources, sample type, and desired purity. Sieving is ideal for field studies or labs with limited equipment, offering quick results with moderate purity. Centrifugation, though more resource-intensive, is superior for research requiring high spore purity, such as molecular analysis or inoculant production. For root samples, centrifugation often outperforms sieving due to its ability to dislodge spores from complex tissues.

Practical Tips for Success

Regardless of method, start with well-preserved samples—store soil or roots at 4°C or freeze-dry to prevent spore degradation. When sieving, ensure sieves are clean and dry to prevent contamination. For centrifugation, calibrate rotor speeds based on spore size and density, and use sterile solutions to maintain sample integrity. Always examine extracted spores under a microscope (400x magnification) to confirm their presence and assess purity. With careful technique, either method can reveal the hidden world of endomycorrhizae spores, unlocking insights into their ecology and function.

Spore Prints Longevity: How Long Do They Remain Viable for Germination?

You may want to see also

Microscopic Preparation: How to mount and stain spores for clear visualization under a microscope

Endomycorrhizae spores, though microscopic, play a pivotal role in soil health and plant nutrition. To observe these spores effectively, proper mounting and staining techniques are essential. The process begins with collecting soil samples from the rhizosphere, the region of soil directly influenced by plant roots. Sieving the soil through a 2 mm mesh helps remove large debris, while subsequent sieving through a 45 µm mesh isolates the spore-sized fraction. This concentrated sample is then ready for microscopic preparation.

Mounting the spores on a slide requires precision. Place a small drop of water or a mounting medium like glycerol on a clean microscope slide. Using a fine brush or pipette, transfer a tiny amount of the sieved soil suspension onto the drop. Gently spread the suspension to create a thin, even layer, ensuring spores are not clumped. Cover the sample with a cover slip, taking care to avoid air bubbles, which can obscure visualization. For added stability, seal the edges of the cover slip with clear nail polish. This preparation method ensures spores are immobilized and evenly distributed for examination.

Staining enhances contrast and highlights spore structures under the microscope. Common stains like trypan blue or ink vinegar are effective for endomycorrhizae spores. Prepare a 0.05% trypan blue solution in a mixture of lactic acid, glycerol, and distilled water (1:1:1 ratio). Place the mounted slide in a staining jar filled with this solution and heat gently at 60°C for 1–2 minutes. This process softens the spore walls, allowing the stain to penetrate. After staining, rinse the slide with distilled water to remove excess dye and blot dry. The stained spores will now exhibit distinct features, such as walls and contents, facilitating detailed observation.

While mounting and staining are straightforward, several cautions ensure success. Overheating during staining can damage spore structures, so monitor the temperature carefully. Using too much soil suspension can lead to overcrowding on the slide, making individual spores difficult to distinguish. Always handle slides and cover slips with clean hands or gloves to prevent contamination. For beginners, practicing with known spore samples can build confidence before working with field-collected material.

In conclusion, mastering the art of mounting and staining endomycorrhizae spores transforms them from invisible soil components to observable entities under the microscope. This technique not only aids in identifying spore types but also deepens our understanding of their ecological significance. With attention to detail and adherence to best practices, even novice microscopists can achieve clear, informative visualizations of these vital organisms.

Crafting the Majestic Pegasus in Spore: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

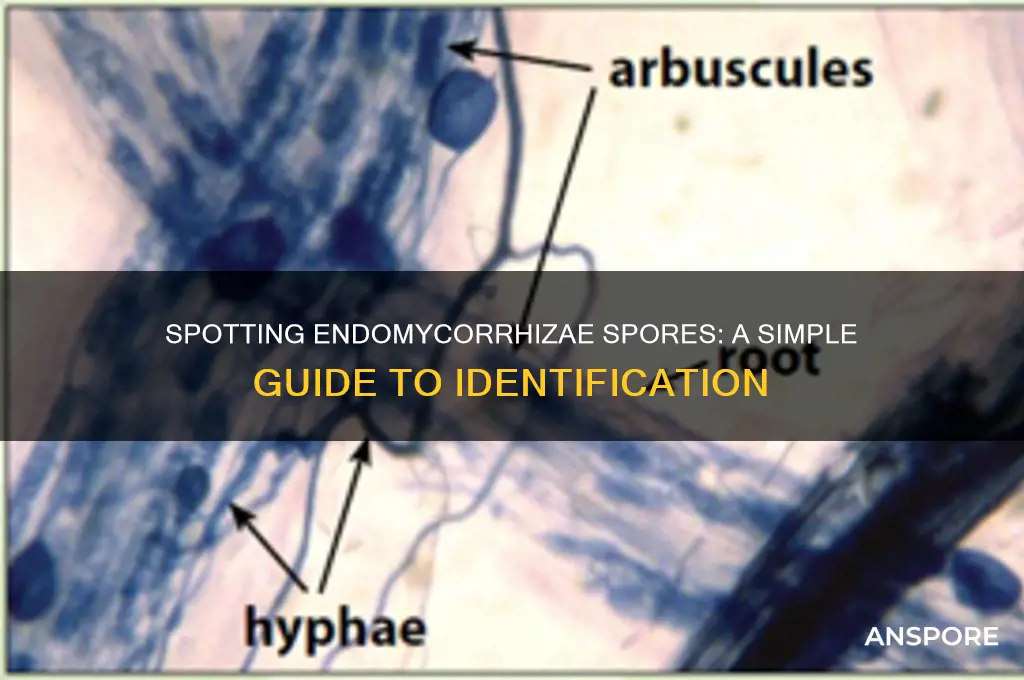

Microscopic Identification: Key features to recognize endomycorrhizae spores, such as size, shape, and color

Endomycorrhizae spores, though microscopic, exhibit distinct features that allow for their identification under a microscope. Size is a critical characteristic, with most spores ranging from 20 to 200 micrometers in diameter. This variability is influenced by the species and environmental conditions, making precise measurement essential for accurate identification. A calibrated eyepiece micrometer can aid in determining spore size, ensuring consistency across observations.

Shape is another defining feature, with endomycorrhizae spores typically presenting as globose, subglobose, or ellipsoid. Some species may display unique shapes, such as peanut-like or irregular forms, which can serve as diagnostic traits. For instance, *Glomus* species often produce spherical spores, while *Gigaspora* spores are characterized by their large, irregular shapes. Observing the spore’s surface texture, whether smooth, rough, or ornamented, further refines identification.

Color is a less consistent but still valuable trait, as spores can range from hyaline (colorless) to yellow, brown, or even black. Pigmentation is often species-specific and can be influenced by maturity or environmental factors. For example, mature *Sclerocystis* spores are typically brown, while *Acaulospora* spores may remain hyaline. Using a brightfield microscope with proper lighting enhances color detection, though additional staining techniques, such as trypan blue, can highlight internal structures for clearer visualization.

Analyzing these features collectively—size, shape, and color—provides a robust framework for identifying endomycorrhizae spores. However, it’s crucial to cross-reference observations with taxonomic keys or databases, as some species share overlapping characteristics. Practicing with known samples and consulting expert guides can improve accuracy, making microscopic identification a powerful tool in mycorrhizal research and application.

Mastering Spore: Creative Techniques for Crafting Invisible Limbs in Your Creatures

You may want to see also

Advanced Imaging Techniques: Using fluorescence or electron microscopy for detailed spore structure analysis

Endomycorrhizae spores, often invisible to the naked eye, reveal their intricate structures through advanced imaging techniques. Fluorescence microscopy, for instance, employs specific dyes or genetically encoded fluorescent proteins to highlight cellular components, such as chitin in spore walls or lipid droplets within the spore cytoplasm. By exciting these fluorophores with precise wavelengths of light, researchers can visualize the spore’s internal architecture with remarkable clarity. This method is particularly useful for identifying symbiotic fungi like *Glomus* species, where spore wall thickness and hyphal attachments are critical for species identification. For optimal results, use a DAPI stain (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) at a concentration of 1 μg/mL to label DNA, or try FM4-64 (5 μM) to delineate cell membranes, ensuring spores are fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde before staining.

Electron microscopy (EM), on the other hand, offers unparalleled resolution for examining spore ultrastructure. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) can reveal details as small as 0.1 nanometers, allowing researchers to study the lamellate structure of spore walls, the arrangement of lipid bodies, and even the presence of germ pores. To prepare spores for TEM, fix them in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 2 hours, followed by post-fixation in 1% osmium tetroxide. Dehydrate the samples in an ethanol series, embed them in epoxy resin, and section them to 70–90 nm thickness. Caution: Osmium tetroxide is highly toxic; handle in a fume hood and wear appropriate PPE. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) complements TEM by providing 3D surface topography, ideal for studying spore ornamentation or hyphal attachments. Coat samples with a thin layer of gold-palladium before imaging to enhance conductivity and contrast.

Comparing these techniques, fluorescence microscopy is faster and more accessible, making it suitable for live-cell imaging and large-scale studies. However, it lacks the resolution to discern fine ultrastructural details. Electron microscopy, while more labor-intensive and costly, provides definitive structural insights, particularly for taxonomic studies or understanding spore germination mechanisms. For instance, a study on *Rhizophagus irregularis* spores used TEM to confirm the presence of a three-layered wall structure, a key diagnostic feature. Combining both methods can yield comprehensive data, with fluorescence microscopy identifying target structures and EM providing detailed validation.

Practical tips for success: Maintain spore viability during preparation by working at room temperature and minimizing exposure to harsh chemicals. For fluorescence microscopy, use mounting media with anti-fade properties to preserve signal intensity. In EM, ensure proper dehydration to avoid artifact formation, and practice sectioning on less valuable samples before working with limited spore material. Advanced imaging techniques not only enhance our understanding of endomycorrhizae spores but also pave the way for applications in agriculture, ecology, and biotechnology, where precise spore identification and characterization are critical.

Can a Surface Pro Handle Spore? Performance and Compatibility Explored

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The most effective methods include staining techniques such as trypan blue or ink and vinegar, followed by microscopic examination. These stains highlight the spores against the soil or root material, making them easier to see under a compound microscope.

No, endomycorrhizae spores are microscopic, typically ranging from 10 to 100 micrometers in size. A microscope is necessary to observe them clearly.

A magnification of at least 400x is recommended to clearly observe endomycorrhizae spores. Higher magnifications (up to 1000x) can provide more detailed views of spore structures.