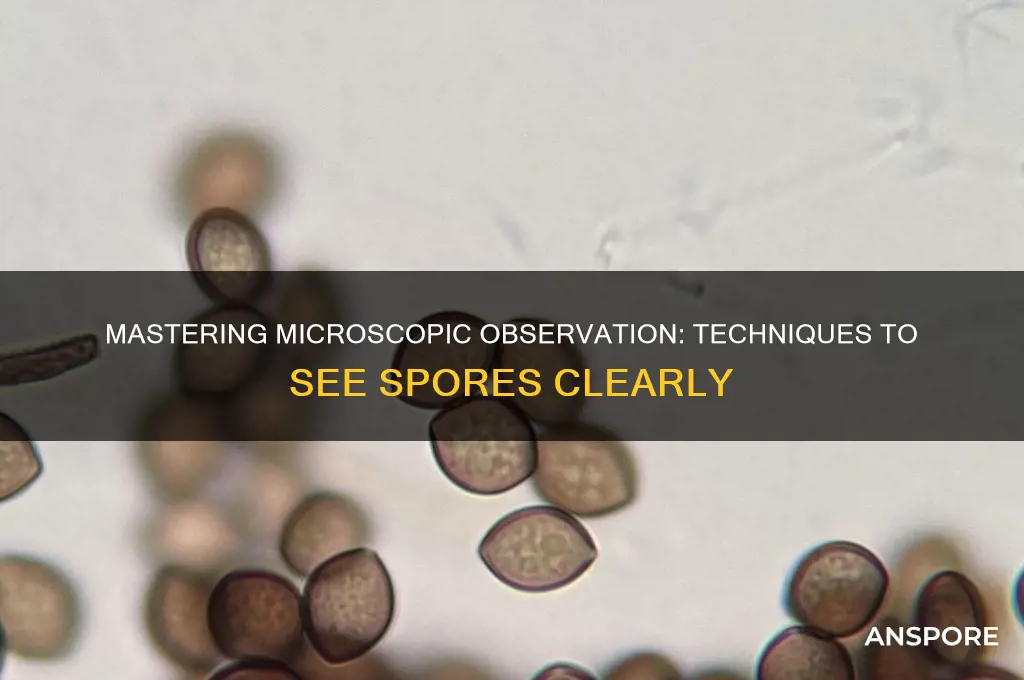

Seeing spores, the microscopic reproductive units of fungi, plants, and some bacteria, requires specific techniques and tools due to their tiny size, typically ranging from 2 to 100 micrometers. To observe spores, one can use a compound microscope with at least 400x magnification, as this allows for clear visualization of their structure and details. Preparing a spore sample involves collecting material from the organism, such as a fungal fruiting body or plant tissue, and placing it on a microscope slide. Techniques like wet mounts, where the sample is suspended in a drop of water or glycerin, or staining with dyes like cotton blue or lactophenol cotton blue, enhance contrast and visibility. Proper lighting and focus are crucial for clear observation, and advanced methods like scanning electron microscopy can provide even greater detail for research purposes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Method | Microscopy |

| Required Equipment | Compound microscope (400x magnification or higher), glass slides, cover slips, tweezers, scalpel, dropper |

| Sample Preparation | Collect spore-bearing material (e.g., mushroom gills, fern undersides, mold colonies) |

| Mounting Technique | Place a small sample on a glass slide, add a drop of water, cover with a cover slip |

| Staining (Optional) | Use cotton blue or methylene blue to enhance visibility |

| Lighting | Use brightfield illumination with a light source beneath the stage |

| Focusing | Adjust coarse and fine focus knobs to bring spores into clear view |

| Spore Identification | Look for small, oval, or spherical structures, often with distinct colors or shapes |

| Alternative Methods | Tape-lift method for mold spores, spore prints for mushrooms |

| Safety Precautions | Avoid inhaling spores; work in a well-ventilated area |

| Common Challenges | Overcrowding on slide, debris obscuring view, improper focus |

| Advanced Techniques | Phase contrast microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) |

| Educational Resources | Mycology textbooks, online microscopy guides, fungal identification apps |

What You'll Learn

- Preparing Slides: Clean slides, use clear tape or water to mount spore-bearing material for observation

- Using a Microscope: Adjust magnification, focus on spores, and use proper lighting for clear visibility

- Identifying Spores: Study shape, size, and color to differentiate between various types of spores

- Collecting Samples: Gather material from plants, fungi, or soil for spore extraction and examination

- Staining Techniques: Apply dyes like cotton blue or lactophenol to enhance spore visibility under microscope

Preparing Slides: Clean slides, use clear tape or water to mount spore-bearing material for observation

Cleanliness is paramount when preparing slides for spore observation. Even a speck of dust or a smudge can obscure your view, turning a clear observation into a frustrating guessing game. Start by washing your slides with mild soap and distilled water, ensuring no residue remains. Rinse thoroughly and dry them with lens tissue or a lint-free cloth to avoid introducing new contaminants. A pristine slide is the foundation for a successful observation, allowing you to focus on the spores rather than distractions.

Mounting spore-bearing material requires precision and the right technique. Clear tape is a simple yet effective method for capturing spores from surfaces like leaves or mushrooms. Place a small piece of transparent tape over the spore-bearing area, press gently, and lift it carefully. Transfer the tape, spore-side down, onto the clean slide. This method preserves the spores’ structure and arrangement, offering a clear view under magnification. For delicate samples, water mounting is preferable. Place a drop of distilled water on the slide, gently deposit the spore- bearing material into the drop, and cover it with a cover slip, ensuring no air bubbles remain. This technique is ideal for observing spores in their natural state, though it requires a steady hand to avoid damaging the sample.

Choosing between tape and water mounting depends on the material and your observational goals. Tape mounting is quick and ideal for dry, sturdy samples, while water mounting suits fragile or moist specimens. For instance, fern spores are best observed using the water method, as it maintains their natural dispersal mechanism. Conversely, mushroom gills are easily captured with tape, providing a clear, intact sample. Experimenting with both methods will help you determine which works best for your specific needs.

Caution is key when handling spore-bearing materials, especially those from fungi or plants that may cause allergies or irritation. Wear gloves and work in a well-ventilated area to minimize exposure. Additionally, ensure your tools—tweezers, scalpels, or brushes—are clean and dedicated to laboratory use to prevent cross-contamination. Proper preparation not only enhances your observation but also ensures safety and accuracy in your work.

In conclusion, preparing slides for spore observation is a blend of art and science. Clean slides, careful mounting techniques, and attention to detail transform a simple sample into a window into the microscopic world. Whether using tape or water, the goal remains the same: to reveal the hidden beauty and complexity of spores. With practice and patience, you’ll master this skill, unlocking new insights into the natural world.

Amanita Spore Prints: Unveiling the Mystery of Their Drop Patterns

You may want to see also

Using a Microscope: Adjust magnification, focus on spores, and use proper lighting for clear visibility

Spores, often invisible to the naked eye, reveal their intricate structures under a microscope. To observe them effectively, start by selecting the appropriate magnification. A 40x objective lens is ideal for initial scanning, offering a balance between detail and field of view. For finer details, switch to a 100x oil immersion lens, which magnifies spores up to 1,000 times their actual size. However, higher magnification reduces the depth of field, so precise focusing becomes critical. Adjust the coarse focus knob first to bring the spores into rough view, then refine with the fine focus knob for sharp clarity. This two-step process ensures you capture the spore’s delicate features without damaging the slide or lens.

Lighting plays a pivotal role in spore visibility. Brightfield microscopy, the most common technique, relies on transmitted light passing through the specimen. For spores, which often lack inherent contrast, adjust the condenser diaphragm to optimize illumination. A slightly closed diaphragm enhances contrast by reducing scattered light, making spore walls and internal structures more distinct. Alternatively, phase contrast microscopy can be employed, which uses interference to highlight transparent structures like spores without staining. This method is particularly useful for live specimens, as it avoids the potential toxicity of dyes. Experiment with lighting techniques to find the best clarity for your sample.

Focusing on spores requires patience and precision. Begin by centering the specimen under the lens, ensuring it’s securely mounted on a clean slide. If using a wet mount, add a coverslip to flatten the sample and reduce distortion. When adjusting focus, move the stage slowly to avoid losing the spores’ position. For oil immersion, apply a drop of immersion oil directly onto the coverslip before switching to the 100x lens. This oil eliminates the air gap between the lens and slide, maximizing resolution. Remember to clean the lens and slide thoroughly after use to prevent oil residue from affecting future observations.

Practical tips can enhance your spore-viewing experience. Always calibrate your microscope before use, ensuring the stage and lenses are aligned. Keep slides and coverslips free of dust and fingerprints, as these can obscure details. For stubborn samples, consider staining with a simple dye like cotton blue or methylene blue to enhance contrast. When working with high magnification, stabilize the microscope on a vibration-free surface to avoid blurring. Finally, document your observations with sketches or digital images, noting magnification and lighting settings for future reference. With these techniques, even the smallest spores become a world of discovery.

Gram-Negative Bacteria: Do They Form Spores? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Identifying Spores: Study shape, size, and color to differentiate between various types of spores

Spores, the microscopic reproductive units of fungi, algae, and some plants, exhibit remarkable diversity in shape, size, and color. These characteristics are not merely aesthetic; they serve as critical identifiers for distinguishing between species. For instance, the spores of *Aspergillus niger* are typically globose to subglobose, measuring 3–5 µm in diameter, while those of *Penicillium* species are often elliptical and smaller, around 2–3 µm. Observing these features under a microscope, preferably at 400x to 1000x magnification, allows for precise classification. A drop of water or mounting medium on a slide can enhance visibility, but avoid overloading the sample to prevent clustering.

Color is another distinguishing trait, often linked to the spore’s maturity or species. For example, *Rust fungi* produce spores in shades of orange or brown, while *Powdery mildew* spores are typically white or gray. Some spores, like those of *Alternaria*, have a dark brown to black hue, making them easily identifiable against a clear background. To accurately assess color, use a brightfield microscope with proper lighting and consider staining techniques, such as cotton blue or lactophenol cotton blue, which can highlight structural details and enhance contrast.

Size is a fundamental parameter in spore identification, often measured along the longest axis. For beginners, a micrometer slide can calibrate the microscope’s scale, ensuring accurate measurements. For example, *Fern spores* range from 20–50 µm, making them visible under lower magnification, while *Yeast spores* are significantly smaller, around 5–10 µm, requiring higher magnification. Consistency in measurement technique is key; always measure multiple spores to account for natural variation within a species.

Shape is perhaps the most visually striking characteristic, varying from spherical to elongated, smooth to ornamented. *Cladosporium* spores, for instance, are often described as lemon-shaped, while *Fusarium* spores are elongated with a distinctive curved appearance. Sketching or photographing spores under the microscope can aid in documentation and comparison. For advanced identification, consult reference guides or databases like the *Index Fungorum*, which provide detailed morphological descriptions and images for thousands of species.

In practice, combining these traits—shape, size, and color—yields a robust identification framework. For example, a spore that is oval, 4–6 µm in length, and pale green is likely from a *Cladophialophora* species. However, caution is necessary; environmental factors like humidity or nutrient availability can subtly alter spore morphology. Always cross-reference observations with multiple samples and, if possible, use molecular techniques like DNA sequencing for confirmation. Mastery of these morphological cues transforms spore identification from guesswork into a precise science.

Do Spores Stain Acid-Fast? Unraveling the Microscopic Mystery

You may want to see also

Collecting Samples: Gather material from plants, fungi, or soil for spore extraction and examination

Spores are microscopic, resilient structures produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, often serving as a means of reproduction and dispersal. To observe them, you first need to collect viable samples from their natural habitats. For plant spores, focus on ferns, mosses, or fungi like mushrooms, as these are prolific spore producers. Gently gather fronds, caps, or gills using clean tools to avoid contamination. Soil samples, rich in bacterial and fungal spores, can be collected by scooping a small amount from the top layer, ensuring it’s free from debris. Proper collection is critical; mishandling can damage spores or introduce foreign particles, skewing your examination.

When collecting fungal material, timing is crucial. Mushrooms release spores most actively when their gills are fully developed but not yet degraded. Use a sharp knife or scalpel to cut the cap or remove a gill segment, placing it spore-side down on a clean surface or slide. For soil samples, a trowel or spoon works well, but sterilize it with alcohol wipes to prevent cross-contamination. Plant samples, like fern leaves, should be collected during their reproductive phase, identifiable by small dots (sori) on the underside of fronds. Handle these delicately to keep the spores intact for extraction.

Extraction methods vary by source. For fungi, cover the spore-bearing surface with a glass slide or tape for a few hours to allow spores to fall naturally. Soil samples require a more involved process: mix a small amount with distilled water, agitate gently, and filter through a fine mesh to concentrate spores. Plant spores can be extracted by placing the reproductive parts in a paper bag or envelope, allowing them to dry and release spores naturally. Each method preserves spore integrity, ensuring they remain observable under a microscope.

Caution is essential during collection and extraction. Wear gloves to avoid transferring oils or contaminants to the samples. Label all containers with collection details (date, location, source) to maintain traceability. Store samples in cool, dry conditions until ready for examination. Improper handling, such as crushing fungal caps or overheating soil, can destroy spores or alter their structure. By following these steps, you’ll gather high-quality material that yields clear, detailed spore observations, whether for scientific study or personal curiosity.

Mastering Spore's Glow Effect: Enhancing Antler Designs with Radiant Light

You may want to see also

Staining Techniques: Apply dyes like cotton blue or lactophenol to enhance spore visibility under microscope

Spores, often microscopic and translucent, can be nearly invisible under a standard microscope. Staining techniques address this challenge by introducing dyes that bind to spore structures, making them stand out against their surroundings. Cotton blue and lactophenol cotton blue are two commonly used stains, each with unique properties that enhance spore visibility. These dyes not only highlight spore walls but also help differentiate them from debris or other microorganisms, ensuring accurate identification.

To apply these staining techniques, begin by preparing a spore suspension. Place a small sample of the material containing spores (e.g., fungal hyphae or plant tissue) onto a microscope slide. Add a drop of water or sterile buffer to create a thin, even layer. Next, heat-fix the sample by gently passing the slide over a flame or using a slide warmer. This step adheres the spores to the slide, preventing them from washing away during staining. Once fixed, add a single drop of cotton blue or lactophenol cotton blue to the sample. Lactophenol cotton blue, a mixture of phenol, glycerin, lactic acid, and cotton blue dye, is particularly effective due to its preservative properties, which also help mount the sample for long-term observation.

The staining process is both art and science. Allow the dye to sit on the slide for 3–5 minutes, ensuring complete coverage. Blot excess stain gently with absorbent paper, taking care not to disturb the sample. For lactophenol cotton blue, a coverslip can be added after staining, sealing the sample and preserving it for extended periods. When viewed under a microscope, stained spores will appear distinctly blue against a lighter background, their walls and structures clearly defined. This contrast is critical for identifying spore morphology, such as size, shape, and surface features, which are essential for taxonomic classification.

While these techniques are effective, they require precision and caution. Over-staining can obscure details, while under-staining may leave spores inadequately visible. Always use fresh dye solutions, as old or contaminated reagents can yield poor results. For beginners, practice with known spore samples to familiarize yourself with the process and expected outcomes. Additionally, ensure proper ventilation when working with phenol-based stains like lactophenol cotton blue, as phenol is toxic and should be handled with care.

In conclusion, staining techniques using dyes like cotton blue or lactophenol cotton blue are indispensable tools for visualizing spores under a microscope. By following precise steps and exercising caution, even novice microscopists can achieve clear, detailed images of these microscopic structures. Mastery of these techniques not only enhances observational skills but also opens doors to deeper exploration of fungal, bacterial, and plant biology.

Are Ringworm Spores Airborne? Uncovering the Truth About Transmission

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

To see spores, you will need a microscope with at least 400x magnification, a clean glass slide, a cover slip, and a light source. Some spores may require staining with a dye like methylene blue for better visibility.

Spores can be found in various environments, such as on moldy bread, ferns, mushrooms, or in soil samples. You can also collect spores from plants like ferns by placing a sheet of paper under the fronds and waiting for them to drop.

To prepare a spore sample, place a small amount of the material (e.g., mold, fern, or soil) in a drop of water on a glass slide. Gently spread it with a toothpick, cover with a cover slip, and examine under the microscope. For better contrast, add a stain like methylene blue before covering.