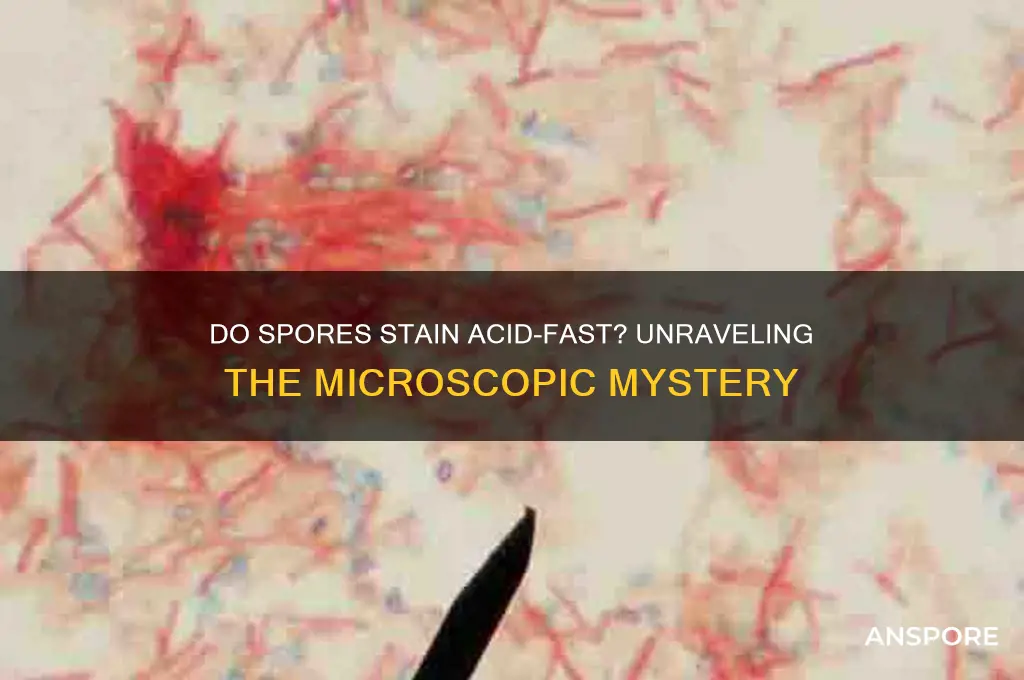

The question of whether spores stain with acid-fast techniques is a critical one in microbiology, particularly in the identification and differentiation of certain bacterial species. Acid-fast staining, a method commonly used to detect *Mycobacterium* species, relies on the unique cell wall composition of these bacteria, which resists decolorization by acid-alcohol. While the primary focus of this staining method is the bacterial cell wall, the behavior of spores—dormant, highly resistant structures produced by some bacteria—under acid-fast staining conditions is less straightforward. Spores, known for their robust outer layers, may exhibit varying degrees of staining depending on their structure and the specific staining protocol used. Understanding whether and how spores stain with acid-fast techniques is essential for accurate microbial identification and diagnostic applications, especially in clinical and environmental settings where spore-forming bacteria may coexist with acid-fast organisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Staining Result | Spores do not typically stain with the acid-fast technique. |

| Reason | Spores have a thick, lipid-rich cell wall that resists decolorization by acid-alcohol, a key step in acid-fast staining. |

| Exception | Some spores, like those of Mycobacterium species, may retain the primary stain (e.g., carbol fuchsin) due to their waxy cell wall, but they are not considered acid-fast because they do not resist decolorization. |

| Appearance | Spores may appear as lightly stained or unstained structures in acid-fast stained smears. |

| Contrast | Vegetative cells of acid-fast bacteria (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis) stain red and remain so after acid-alcohol treatment, while spores do not. |

| Alternative Staining | Spores are better visualized with methods like the Wirtz-Conklin or Schaeffer-Fulton stains, which specifically target spore structures. |

| Clinical Relevance | Acid-fast staining is primarily used for detecting acid-fast bacteria, not spores, in clinical samples. |

Explore related products

$51.99

What You'll Learn

- Acid-Fast Stain Mechanism: How acid-fast stain works on bacterial cell walls, including mycolic acid retention

- Spores vs. Acid-Fast Bacteria: Differences in spore and mycobacterial cell wall structures affecting staining

- Common Acid-Fast Spores: Identification of spore-forming bacteria that may react to acid-fast staining

- Staining Techniques: Steps and reagents used in acid-fast staining for accurate results

- Clinical Relevance: Importance of acid-fast staining in diagnosing mycobacterial infections like tuberculosis

Acid-Fast Stain Mechanism: How acid-fast stain works on bacterial cell walls, including mycolic acid retention

Spores, the resilient survival structures of certain bacteria, present a unique challenge in staining due to their impermeable nature. Unlike vegetative bacterial cells, spores possess a thick, multilayered coat that resists many common staining techniques. This raises the question: can acid-fast staining, a method renowned for its ability to differentiate mycobacteria, effectively penetrate and stain spores?

While acid-fast staining is primarily used to identify mycobacteria, its mechanism relies on the unique composition of their cell walls, particularly the presence of mycolic acids. These long-chain fatty acids create a waxy, hydrophobic barrier that resists decolorization by acid-alcohol, allowing the primary stain (carbol fuchsin) to remain within the cell.

The key to understanding why spores generally don't stain acid-fast lies in their distinct structure. Spores lack the mycolic acid layer found in mycobacteria. Instead, their coat is composed of proteins, peptidoglycan, and dipicolinic acid, which contribute to their resistance to staining and environmental stresses. The absence of mycolic acids means spores lack the crucial component that enables acid-fastness in mycobacteria.

Consequently, when subjected to the acid-fast staining procedure, spores typically decolorize along with non-acid-fast organisms, appearing colorless against the red background of acid-fast bacteria. This highlights the specificity of the acid-fast stain for mycolic acid-containing organisms.

It's important to note that some spore-forming bacteria, like *Nocardia*, possess a cell wall structure similar to mycobacteria and can exhibit acid-fast properties. However, this is an exception rather than the rule. In most cases, the absence of mycolic acids in spores renders them non-acid-fast, emphasizing the importance of understanding the underlying mechanism of staining techniques for accurate microbial identification.

Can Psilocybin Spores Survive Digestion? Exploring the Science Behind It

You may want to see also

Spores vs. Acid-Fast Bacteria: Differences in spore and mycobacterial cell wall structures affecting staining

Spores and acid-fast bacteria, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, exhibit distinct cell wall structures that fundamentally influence their staining properties. Spores, produced by certain bacteria and fungi, are characterized by a thick, multilayered cell wall composed primarily of peptidoglycan, secondary metabolites like dipicolinic acid, and a proteinaceous outer coat. This robust structure provides spores with extreme resistance to heat, chemicals, and desiccation. In contrast, mycobacteria possess a unique cell wall rich in mycolic acids, long-chain fatty acids that form a waxy, hydrophobic barrier. This mycolic acid layer is responsible for the "acid-fast" property, allowing mycobacteria to retain stains like carbol fuchsin even after acid-alcohol decolorization.

The staining behavior of spores and acid-fast bacteria diverges due to these structural differences. Spores typically do not stain acid-fast because their cell wall lacks mycolic acids. Instead, they are often visualized using specialized techniques like the Schaeffer-Fulton stain, which employs heat and malachite green to penetrate the spore’s resistant layers. Acid-fast bacteria, however, are specifically targeted by the Ziehl-Neelsen or Kinyoun stains, which leverage the mycolic acid layer’s ability to retain carbol fuchsin. This distinction is critical in clinical microbiology, where accurate identification of pathogens relies on understanding these staining mechanisms.

To illustrate, consider the practical application in a laboratory setting. When testing a sputum sample for tuberculosis, the Ziehl-Neelsen stain is applied, heating the sample to drive carbol fuchsin into the mycobacterial cell wall. After decolorization with acid-alcohol, mycobacteria remain red (acid-fast), while other microorganisms are decolorized. Spores, if present, would not retain the stain and would appear colorless or require an alternative staining method. This highlights the importance of selecting the appropriate staining technique based on the target organism’s cell wall composition.

A key takeaway is that the structural uniqueness of spores and mycobacteria dictates their staining behavior. While mycobacteria’s mycolic acid-rich wall enables acid-fast staining, spores’ multilayered, mycolic acid-free structure necessitates different approaches. Clinicians and laboratory technicians must recognize these differences to avoid misidentification, ensuring accurate diagnosis and treatment. For instance, mistaking a spore for an acid-fast bacillus could lead to inappropriate antibiotic therapy, underscoring the practical implications of this knowledge.

In summary, the interplay between cell wall structure and staining properties is a cornerstone of microbiological identification. Spores and acid-fast bacteria exemplify how evolutionary adaptations in cell wall composition result in distinct staining behaviors. By understanding these differences, professionals can employ the correct staining techniques, enhancing diagnostic precision and patient outcomes. This nuanced approach is essential in fields where microbial identification directly impacts clinical decision-making.

Exploring Spore-Based Plants: Do They Feature Hanging Roots?

You may want to see also

Common Acid-Fast Spores: Identification of spore-forming bacteria that may react to acid-fast staining

Spores of certain bacteria exhibit unique staining characteristics when subjected to acid-fast techniques, a critical aspect of microbiological identification. Acid-fast staining, traditionally used for mycobacteria, relies on the mycolic acid in their cell walls, which resists decolorization by acid-alcohol. However, some spore-forming bacteria, despite lacking mycolic acid, may retain the primary stain (carbol fuchsin) due to their robust spore coats. This phenomenon can lead to false-positive interpretations if not carefully analyzed. For instance, *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* spores, though not inherently acid-fast, may appear red under certain staining conditions, necessitating additional tests for accurate identification.

To identify spore-forming bacteria that may react to acid-fast staining, follow these steps: First, prepare a heat-fixed smear of the bacterial sample on a glass slide. Apply carbol fuchsin as the primary stain for 5 minutes, followed by heating (either via steam or a flame) to enhance penetration. Decolorize with 3% acid-alcohol for 1–2 minutes, then counterstain with methylene blue or Lugol’s iodine. Examine under oil immersion (1000X magnification). If spores appear red, confirm their identity through additional tests, such as spore staining with malachite green or molecular methods like PCR. This approach ensures differentiation between true acid-fast organisms and spore-forming bacteria with artifactual staining.

A comparative analysis reveals that while mycobacteria like *Mycobacterium tuberculosis* consistently retain the red color due to their waxy cell walls, spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus anthracis* may show variable staining. The spore coat’s chemical composition and thickness influence its interaction with the stain. For example, *B. anthracis* spores, when stained with acid-fast techniques, may retain carbol fuchsin due to their resistant exosporium, but this is not a definitive identifier. In contrast, *Mycobacterium* species exhibit uniform staining across their cell bodies, highlighting the importance of morphological and structural context in interpretation.

Practitioners must exercise caution when interpreting acid-fast staining results for spore-forming bacteria. False positives can occur due to incomplete decolorization or over-staining, particularly in samples with high spore concentrations. To mitigate this, standardize staining protocols, including precise timing and reagent concentrations. For instance, decolorization with 3% acid-alcohol should not exceed 2 minutes to avoid removing the primary stain from true acid-fast organisms. Additionally, always correlate staining results with clinical context and supplementary tests, such as spore morphology or biochemical assays, to ensure accurate identification.

In conclusion, while acid-fast staining is invaluable for identifying mycobacteria, its application to spore-forming bacteria requires careful consideration. Spores of *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* may artifactually retain the primary stain, mimicking acid-fast organisms. By understanding the mechanisms behind this staining behavior and employing rigorous protocols, microbiologists can avoid misidentification. This nuanced approach ensures that acid-fast staining remains a reliable tool in the diagnostic arsenal, even when dealing with the complexities of spore-forming bacteria.

Do Mold Spores Die When They Dry Out? The Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Staining Techniques: Steps and reagents used in acid-fast staining for accurate results

Acid-fast staining is a specialized technique used to differentiate bacteria based on their ability to retain certain dyes, even after treatment with acid and alcohol. This method is particularly crucial for identifying mycobacteria, including *Mycobacterium tuberculosis*, which are known for their waxy cell walls rich in mycolic acids. The question of whether spores stain with acid-fast techniques is relevant, as spores possess a unique, highly resistant structure. However, the focus here is on the precise steps and reagents required to achieve accurate results in acid-fast staining, ensuring clarity and reliability in microbiological analysis.

The process begins with heat fixation of the bacterial smear, which adheres the organisms to the slide and enhances their interaction with the stain. The primary stain, carbol fuchsin, is then applied, typically for 5 minutes with gentle heating. This basic fuchsin dye penetrates the cell wall, staining both acid-fast and non-acid-fast bacteria red. Heating is critical, as it drives the dye through the lipid-rich barriers of mycobacteria. After rinsing, the slide is treated with acid-alcohol (a 1:1 mixture of 95% ethanol and 3% hydrochloric acid) for 3 minutes. This decolorizes non-acid-fast bacteria while leaving acid-fast organisms intact due to their mycolic acid-rich walls, which resist decolorization. Precision in timing and reagent concentration is essential, as over-decolorization can lead to false-negative results.

Following decolorization, the slide is counterstained with methylene blue or Loeffler’s methylene blue for 30 seconds to 1 minute. This stains the non-acid-fast bacteria blue, providing a clear contrast against the red acid-fast organisms. The choice of counterstain can influence background clarity, with methylene blue offering a sharper distinction. After a final rinse and air-drying, the slide is ready for examination under a microscope. Proper execution of these steps ensures that acid-fast bacteria appear bright red against a blue background, while non-acid-fast bacteria and spores, if present, will appear blue.

Caution must be exercised in handling reagents, particularly acid-alcohol, which is corrosive and requires adequate ventilation. Heat application during staining should be controlled to avoid overheating, which can damage the slide or alter staining results. Additionally, while spores themselves do not typically retain the primary stain due to their distinct composition, they may appear as blue structures under the counterstain, highlighting the importance of interpreting results within the context of the organism’s morphology and known characteristics.

In conclusion, acid-fast staining is a meticulous process requiring attention to detail in both technique and reagent use. By following these steps precisely, microbiologists can reliably differentiate acid-fast bacteria from other organisms, including spores, contributing to accurate diagnosis and research. Mastery of this technique is invaluable in clinical and laboratory settings, particularly in the identification of mycobacterial infections.

Do Moss Plants Produce Spores? Unveiling the Truth About Moss Reproduction

You may want to see also

Clinical Relevance: Importance of acid-fast staining in diagnosing mycobacterial infections like tuberculosis

Acid-fast staining is a critical diagnostic tool in the detection of mycobacterial infections, particularly tuberculosis (TB), a disease that remains one of the top 10 causes of death worldwide. The unique cell wall composition of mycobacteria, rich in mycolic acids, allows them to retain the primary stain (carbol fuchsin) even after an acid-alcohol decolorization step, hence the term "acid-fast." This characteristic staining pattern—bright red bacilli against a blue background—provides rapid, presumptive evidence of *Mycobacterium tuberculosis* in clinical specimens like sputum, making it an indispensable technique in resource-limited settings where advanced diagnostics are unavailable.

From a practical standpoint, the acid-fast staining procedure is straightforward yet requires precision. A heat-fixed smear of the specimen is stained with carbol fuchsin for 5 minutes, followed by decolorization with acid-alcohol for 15–30 seconds, and counterstaining with methylene blue for 30 seconds. The entire process takes less than 15 minutes, yielding results that guide immediate clinical decisions. For instance, a positive acid-fast smear in a patient with symptoms of TB (e.g., chronic cough, weight loss, fever) warrants urgent initiation of anti-TB therapy, even as confirmatory tests like culture or molecular assays are pending. This rapid turnaround is vital for diseases like TB, where delayed treatment increases transmission risk.

Comparatively, while molecular tests like Xpert MTB/RIF offer higher sensitivity and can detect rifampicin resistance, they are costly and require specialized equipment. Acid-fast staining, in contrast, is inexpensive, requires minimal infrastructure, and remains the backbone of TB diagnosis in low-income countries. However, its limitations—such as low sensitivity in paucibacillary specimens (e.g., extrapulmonary TB) and inability to differentiate between *M. tuberculosis* and nontuberculous mycobacteria—highlight the need for complementary diagnostics. For example, a negative acid-fast smear does not rule out TB, especially in HIV-coinfected patients, where bacterial loads may be lower.

Persuasively, the clinical relevance of acid-fast staining extends beyond TB. It is equally valuable in diagnosing other mycobacterial infections, such as leprosy (*Mycobacterium leprae*) and infections caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) like *Mycobacterium avium* complex (MAC). In leprosy, acid-fast bacilli are detected in skin smears from patients with the multibacillary form, guiding treatment decisions. For NTM infections, while acid-fast staining cannot differentiate species, it provides a rapid indication of mycobacterial presence, prompting further speciation and susceptibility testing. This versatility underscores its enduring importance in clinical microbiology.

In conclusion, acid-fast staining remains a cornerstone of mycobacterial diagnosis, particularly for TB, due to its simplicity, speed, and cost-effectiveness. While it is not without limitations, its ability to provide rapid, actionable results in diverse clinical settings makes it an irreplaceable tool. Clinicians and laboratory professionals must remain adept at interpreting acid-fast smears, ensuring timely diagnosis and treatment of mycobacterial infections, especially in regions with high TB burden. Mastery of this technique, combined with awareness of its constraints, optimizes patient care and public health outcomes.

Bacteria Spores: Hyperthermophiles, Thermophiles, or Neither? Exploring Heat Tolerance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spores can stain with acid-fast techniques, but they typically retain the primary stain (e.g., carbol fuchsin) and appear red, as they are highly resistant to decolorization by acid-alcohol.

Spores appear acid-fast due to their thick, waxy cell walls composed of sporopollenin, which resists decolorization by acid-alcohol during the staining process.

While most bacterial spores (e.g., *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*) stain acid-fast, fungal spores may not always retain the stain due to differences in their cell wall composition.