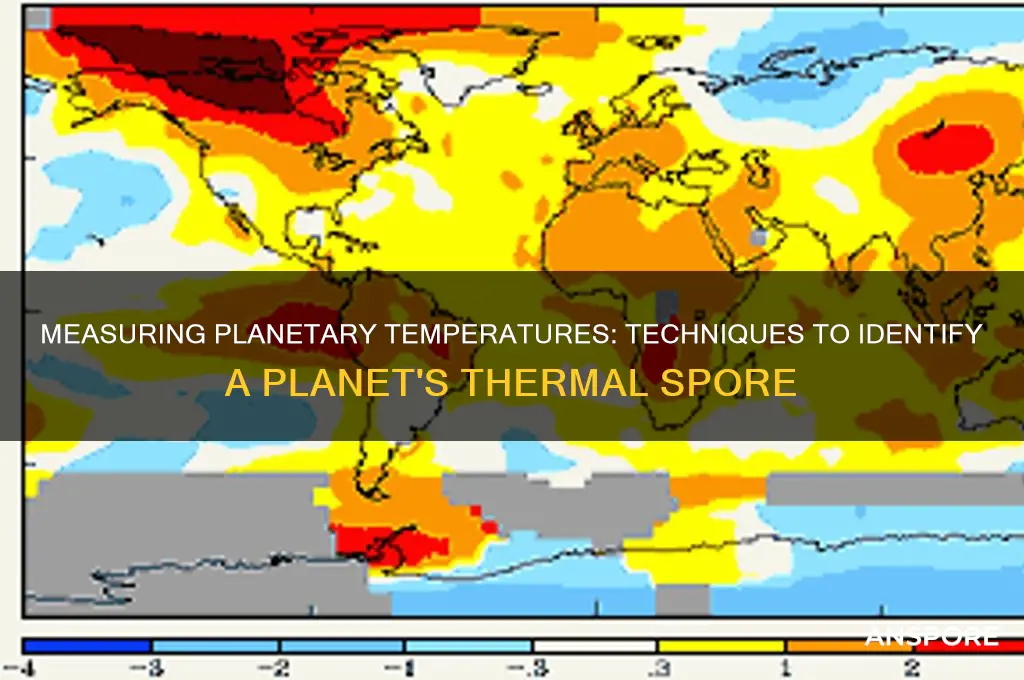

Determining a planet's temperature is a critical aspect of understanding its habitability, atmospheric composition, and potential for supporting life. Scientists employ various methods to measure planetary temperatures, including analyzing thermal emissions, studying atmospheric gases, and using remote sensing techniques. One intriguing approach involves examining temperature-sensitive spores, which can act as natural indicators of environmental conditions. These spores, often found in extremophile organisms, exhibit unique properties that change in response to temperature variations, offering a biological lens through which to assess a planet's thermal characteristics. By studying these spores, researchers can gain valuable insights into a planet's climate, surface conditions, and potential for hosting life, bridging the gap between biology and planetary science.

What You'll Learn

- Thermal Emission Spectroscopy: Analyzing infrared radiation emitted by planets to determine surface temperature

- Albedo Measurement: Calculating reflectivity to understand heat absorption and planetary temperature

- Atmospheric Composition: Studying gases like CO2 and methane to assess heat retention

- Orbital Distance: Using distance from the star to estimate temperature range

- Temperature Probes: Deploying spacecraft instruments to directly measure planetary temperatures

Thermal Emission Spectroscopy: Analyzing infrared radiation emitted by planets to determine surface temperature

Planets don't come with thermometers, so scientists rely on clever techniques to gauge their surface temperatures. One powerful method is thermal emission spectroscopy, which decodes the infrared radiation planets naturally emit. Unlike visible light, infrared is heat radiation, and its intensity and wavelength distribution act as a fingerprint, revealing the temperature of the emitting surface.

Imagine a blacksmith's forge. The glowing metal emits visible light, but it's also radiating intensely in the infrared, invisible to our eyes. Thermal emission spectroscopy captures this invisible heat signature, translating it into temperature data.

The process begins with a telescope equipped with a spectrograph, an instrument that splits incoming light into its component wavelengths, like a prism. When observing a planet, the spectrograph captures the infrared radiation emanating from its surface. This spectrum isn't a smooth curve; it's riddled with peaks and valleys, each corresponding to the absorption and emission characteristics of specific molecules in the planet's atmosphere and on its surface. By analyzing these features, scientists can identify the presence of certain gases and minerals, but crucially, they can also determine the temperature at which the planet is radiating.

Hotter objects emit more radiation at shorter wavelengths, while cooler objects emit more at longer wavelengths. This relationship, described by Planck's law, allows scientists to calculate the planet's surface temperature by analyzing the shape and intensity of its thermal emission spectrum.

Thermal emission spectroscopy isn't without its challenges. Atmospheres can absorb and scatter infrared radiation, complicating the interpretation of the spectrum. Additionally, the technique is most effective for planets with thin or transparent atmospheres, as thick atmospheres can mask the surface signal. Despite these limitations, thermal emission spectroscopy remains a vital tool for exoplanet characterization, providing valuable insights into the temperature regimes of distant worlds. It allows us to distinguish between scorching hot Jupiters and potentially habitable rocky planets, guiding our search for extraterrestrial life.

Mastering the Art of Obtaining a Perfect White Spore Print

You may want to see also

Albedo Measurement: Calculating reflectivity to understand heat absorption and planetary temperature

Planets don't wear thermometers, so scientists rely on clever tricks to gauge their temperatures. One powerful tool is albedo measurement, which quantifies a planet's reflectivity. Imagine a snow-covered planet versus a charcoal-black one – the snow reflects sunlight, staying cooler, while the charcoal absorbs it, heating up. Albedo, measured on a scale from 0 (perfect absorber) to 1 (perfect reflector), reveals this crucial difference.

High albedo planets, like Venus with its thick, reflective clouds (albedo around 0.75), bounce much sunlight back into space, keeping surface temperatures relatively cooler despite their proximity to the Sun. Conversely, low albedo planets, like Mercury with its dark, rocky surface (albedo around 0.1), absorb more sunlight, leading to scorching temperatures.

Measuring albedo isn't as simple as holding up a mirror. Scientists use spectrometers on spacecraft to analyze the wavelengths of light reflected by a planet. By comparing the intensity of incoming sunlight to the reflected light at different wavelengths, they can calculate the planet's albedo. This data, combined with knowledge of the planet's distance from its star and atmospheric composition, allows them to estimate surface temperature.

Think of it like this: albedo is the planet's sunscreen factor. A high SPF (albedo) means less harmful (heating) radiation reaches the surface. Understanding a planet's albedo is crucial for deciphering its climate, habitability, and even its potential for supporting life.

For aspiring planetary scientists, albedo measurement offers a fascinating glimpse into the intricate dance between sunlight and planetary surfaces. By deciphering this reflectivity code, we unlock secrets about distant worlds, from their scorching deserts to their icy poles, and perhaps even find clues about our own planet's past and future.

Do Fungi and Mold Produce Spores? Understanding Their Reproduction Process

You may want to see also

Atmospheric Composition: Studying gases like CO2 and methane to assess heat retention

The Earth's atmosphere is a complex mixture of gases, with nitrogen and oxygen making up the majority. However, it's the trace gases, such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4), that play a critical role in regulating the planet's temperature. These gases have the ability to absorb and re-emit infrared radiation, creating a natural greenhouse effect that keeps the Earth warm enough to support life. To understand a planet's temperature, scientists often study its atmospheric composition, particularly the concentrations of CO2 and methane, which can provide valuable insights into the planet's heat retention capabilities.

Analyzing Gas Concentrations:

Measuring the concentrations of CO2 and methane in a planet's atmosphere is crucial for assessing its temperature. On Earth, CO2 levels have increased from approximately 280 parts per million (ppm) in pre-industrial times to over 420 ppm today, primarily due to human activities like burning fossil fuels. This increase has led to a rise in global temperatures, highlighting the significance of monitoring these gases. Methane, although present in smaller quantities (around 1.8 ppm), is even more potent at trapping heat, with a global warming potential 28-36 times that of CO2 over a 100-year period. By studying these gas concentrations, scientists can estimate a planet's greenhouse effect and predict its temperature trends.

Comparative Planetology:

Comparing the atmospheric compositions of different planets can provide valuable insights into the relationship between gases and temperature. For instance, Venus has a thick atmosphere composed mostly of CO2, with surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead. In contrast, Mars has a thin atmosphere with low CO2 levels, resulting in frigid temperatures. By examining these extremes, scientists can better understand the role of atmospheric gases in heat retention. A practical tip for aspiring astronomers is to use spectral analysis tools, which can identify the unique fingerprints of gases like CO2 and methane in a planet's atmosphere, allowing for remote temperature assessments.

Instructive Guide to Gas-Temperature Relationships:

To assess a planet's temperature based on its atmospheric composition, follow these steps: (1) Measure the concentrations of CO2 and methane using remote sensing techniques or in-situ probes. (2) Calculate the greenhouse effect by considering the gases' radiative forcing, which quantifies their impact on the planet's energy balance. (3) Apply climate models to simulate the planet's temperature response to its atmospheric composition. Caution should be exercised when interpreting results, as other factors like albedo (reflectivity) and atmospheric circulation can also influence temperature. By combining these methods, scientists can develop a comprehensive understanding of a planet's temperature and its relationship to atmospheric gases.

Persuasive Argument for Monitoring Atmospheric Gases:

The study of atmospheric composition is not just an academic exercise; it has real-world implications for understanding and mitigating climate change. By monitoring CO2 and methane levels, scientists can track the effectiveness of emission reduction efforts and inform policy decisions. For example, the Paris Agreement aims to limit global warming to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, which requires significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Practical tips for individuals include supporting renewable energy initiatives, reducing personal carbon footprints, and advocating for evidence-based climate policies. As we continue to explore and study other planets, the lessons learned from atmospheric composition analysis can inform our understanding of Earth's climate and guide efforts to protect our planet's temperature balance.

Wet Shirts and Mold: Do Damp Fabrics Shield or Spread Spores?

You may want to see also

Orbital Distance: Using distance from the star to estimate temperature range

The temperature of a planet is fundamentally tied to its distance from its star. This relationship, governed by the inverse square law, dictates that the intensity of stellar radiation decreases with the square of the distance from the star. For instance, if Planet A orbits at twice the distance of Planet B, it receives only one-fourth the stellar energy. This principle forms the basis for estimating a planet's temperature range using its orbital distance.

To apply this concept, start by calculating the planet's distance from its star in astronomical units (AU), where 1 AU is the average Earth-Sun distance. Next, use the formula for effective temperature: *T = (L / (16πσD^2))^(1/4)*, where *T* is temperature, *L* is the star's luminosity, *σ* is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, and *D* is the orbital distance in AU. For a quick estimate, compare the planet's distance to Earth's. A planet at 0.5 AU receives four times the solar energy, while one at 2 AU gets one-fourth. This method provides a baseline temperature before accounting for atmospheric effects.

However, orbital distance alone doesn’t tell the full story. Planetary atmospheres play a critical role in modifying temperature through greenhouse effects or albedo. For example, Venus, despite being closer to the Sun than Earth, has a far hotter surface due to its thick CO2 atmosphere. Conversely, Mars, farther from the Sun, has a thin atmosphere that fails to retain heat. Thus, while orbital distance provides a starting point, atmospheric composition and pressure must be considered for accurate temperature predictions.

Practical application of this method is evident in exoplanet studies. Astronomers use orbital distance to classify exoplanets as "hot Jupiters" (close-orbiting gas giants) or "super-Earths" in habitable zones. For instance, Kepler-186f, orbiting its red dwarf star at 0.4 AU, lies within the habitable zone due to the star’s lower luminosity. By combining orbital distance with stellar properties, scientists narrow down candidates for potentially habitable worlds.

In summary, orbital distance is a powerful tool for estimating planetary temperatures, but it’s just one piece of the puzzle. Pairing this method with atmospheric analysis and stellar characteristics yields more precise results. Whether studying our solar system or distant exoplanets, understanding this relationship is key to unraveling the thermal mysteries of planets.

Microscopic Insights: Counting Spores per Ascus Under the Lens

You may want to see also

Temperature Probes: Deploying spacecraft instruments to directly measure planetary temperatures

Directly measuring a planet's temperature isn't as simple as sticking a thermometer in the ground. Planetary surfaces can be inhospitable, with extreme pressures, corrosive atmospheres, and unpredictable terrain. This is where temperature probes, deployed by spacecraft, become invaluable tools. These instruments are designed to withstand the rigors of space travel and planetary entry, providing scientists with precise thermal data from alien worlds.

Example: The Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity rover carries a suite of instruments, including the Rover Environmental Monitoring Station (REMS). REMS includes a temperature sensor mounted on the rover's mast, capable of measuring air temperature at a height of 1.6 meters above the Martian surface. This data has been crucial in understanding Mars' daily and seasonal temperature fluctuations.

Deploying temperature probes requires careful planning and engineering. Probes must be robust enough to survive the harsh conditions of space travel, including extreme temperatures, radiation exposure, and the violent forces of atmospheric entry. Upon landing, they need to be able to withstand the planet's environment, whether it's the crushing pressure of Venus or the frigid vacuum of Europa. Analysis: Material selection is critical. Probes often utilize high-temperature alloys, ceramics, and specialized coatings to endure extreme conditions. For example, the Galileo probe that descended into Jupiter's atmosphere in 1995 was equipped with a heat shield made of carbon phenolic, a material capable of withstanding temperatures exceeding 16,000 degrees Celsius.

Takeaway: The success of temperature probes hinges on meticulous engineering and material science, ensuring they can function reliably in the most unforgiving environments.

Different planets demand different probe designs. For Venus, with its scorching surface temperatures and corrosive sulfuric acid clouds, probes need to be highly heat-resistant and chemically inert. In contrast, probes destined for the icy moons of Jupiter or Saturn must be able to operate in extremely cold temperatures and potentially penetrate thick ice crusts. Comparative: The Huygens probe, which landed on Titan in 2005, was equipped with a heat shield for atmospheric entry and a suite of instruments designed to function in the moon's frigid methane lakes. This contrasts with the design of the Venera probes sent to Venus, which prioritized heat resistance and corrosion protection.

Practical Tip: When designing temperature probes, consider not only the target planet's average temperature but also its extremes, atmospheric composition, and potential surface hazards.

Temperature probes provide invaluable data for understanding planetary climates, geological processes, and potential habitability. By directly measuring temperatures at various depths and locations, scientists can construct detailed thermal profiles of planets, revealing insights into their internal heat sources, atmospheric circulation patterns, and even the presence of subsurface oceans. Persuasive: Investing in the development of advanced temperature probes is crucial for expanding our knowledge of the solar system and beyond. These instruments are the key to unlocking the secrets hidden beneath the surfaces of alien worlds, paving the way for future exploration and potentially even the search for extraterrestrial life.

Does Therapure Air Purifier Effectively Remove Spores from Indoor Air?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

It appears there might be a typo or confusion in the term. If you're referring to measuring a planet's temperature, it typically involves analyzing thermal radiation emitted by the planet using space probes, telescopes, or spectral data.

Scientists measure a planet's temperature by studying its thermal emissions, often using infrared sensors on spacecraft or telescopes. They analyze the planet's albedo (reflectivity) and atmospheric composition to calculate surface and atmospheric temperatures.

In the game *Spore*, planetary temperatures are part of the planet's characteristics and are not measured by the player. The game assigns temperature ranges (e.g., hot, cold, or temperate) based on the planet's proximity to its star and atmospheric conditions.

The term "spore" typically refers to a reproductive structure in plants, fungi, or bacteria and is unrelated to measuring planetary temperature. If you meant something else, please clarify for a more accurate answer.