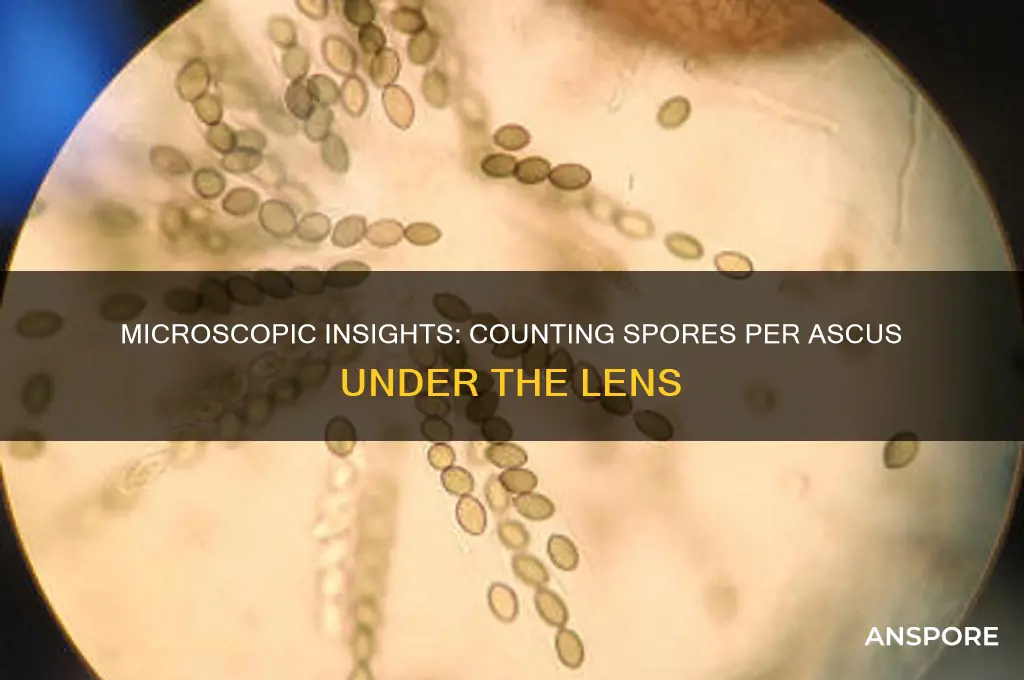

When examining fungal structures under a microscope, one of the key features to observe is the number of spores contained within an ascus, a sac-like structure characteristic of Ascomycota fungi. The typical number of spores per ascus is eight, a feature often referred to as octosporic. However, this count can vary depending on the fungal species, with some producing fewer or more spores. Accurately identifying the number of spores per ascus is crucial for taxonomic classification and understanding fungal reproduction. Under proper magnification and staining techniques, these spores appear as distinct, often neatly arranged structures within the ascus, allowing for precise enumeration and analysis.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of spores per ascus | Typically 8 |

| Arrangement of spores | Linear or in a row |

| Visibility under microscope | Clearly visible |

| Shape of spores | Elliptical or oval |

| Color of spores | Usually hyaline |

| Size of spores | Varies by species |

| Ascus structure | Sac-like or cylindrical |

| Method of spore release | Operculate or inoperculate |

| Common fungi with 8-spored asci | Saccharomyces, Aspergillus (some species) |

| Exceptions (number of spores) | Some fungi may have 1-4 or more than 8 spores per ascus |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Ascus Structure and Spore Arrangement

The ascus, a sac-like structure in Ascomycete fungi, is a marvel of microscopic architecture. Typically, each ascus contains eight spores, a consistent arrangement that serves as a diagnostic feature for this fungal group. When viewed under a microscope, these spores appear as neatly packaged, lens-shaped cells, often aligned in a linear or circular pattern within the ascus. This precise organization is not merely aesthetic; it reflects the ascus's role in spore dispersal and fungal reproduction. Understanding this structure is crucial for mycologists and microbiologists, as it aids in species identification and the study of fungal life cycles.

To observe the ascus and its spores effectively, follow these steps: prepare a slide by placing a small sample of the fungal tissue in a drop of water or mounting medium, cover it with a coverslip, and examine under a compound microscope at 400x to 1000x magnification. The key is to ensure the sample is thin enough to allow light to pass through, enhancing visibility. Under proper conditions, the ascus will appear as a translucent, elongated sac, with the spores inside clearly distinguishable. Note that the number of spores per ascus is usually eight, but variations can occur due to species differences or developmental anomalies.

From a comparative perspective, the ascus structure contrasts with other fungal spore-bearing structures, such as the basidium in Basidiomycetes, which typically bears four spores externally. The enclosed nature of the ascus provides protection for the spores, ensuring their viability during dispersal. This internal arrangement also allows for efficient ejection mechanisms, where the spores are forcibly released through a small pore, or operculum, at the tip of the ascus. Such adaptations highlight the evolutionary sophistication of Ascomycetes in ensuring successful reproduction.

Practical tips for enhancing observation include using differential staining techniques, such as cotton blue or lactophenol cotton blue, to increase contrast between the ascus wall and the spores. Additionally, adjusting the microscope's condenser and light intensity can improve clarity. For beginners, starting with common Ascomycete species like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* or *Penicillium* can provide clear, textbook examples of ascus structure. Advanced users might explore less common species to observe variations in spore number or arrangement, contributing to a deeper understanding of fungal diversity.

In conclusion, the ascus's structure and spore arrangement are not only fascinating but also functionally significant. By mastering the techniques for observing these microscopic features, one gains insights into the intricate world of fungi. Whether for academic research, medical diagnostics, or personal curiosity, the ability to identify and analyze ascus structure is a valuable skill. With practice and attention to detail, even the subtlest variations in spore arrangement become apparent, opening doors to a richer appreciation of fungal biology.

Mastering Spore: A Beginner's Guide to Evolving Your Creature

You may want to see also

Microscopic Techniques for Spore Counting

The number of spores per ascus visible under a microscope depends heavily on the fungal species and the magnification used. Asci, the sac-like structures containing spores, vary in size and spore count across different fungi. For instance, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* typically contains 1 to 4 spores per ascus, while *Aspergillus* species may have 8 or more. To accurately count spores, a systematic approach combining proper sample preparation and microscopic techniques is essential.

Sample Preparation: The Foundation of Accuracy

Begin by preparing a clean, thin slide to avoid overcrowding, which can obscure individual spores. Heat-fixing the sample at 50–60°C for 5 minutes stabilizes the asci and prevents distortion during staining. Use a 10% aqueous solution of cotton blue or lactophenol blue to stain the spores, enhancing contrast and visibility. For fungi with thick cell walls, a brief treatment with 10% KOH can soften the tissue, allowing better spore release. Always use a coverslip to ensure even distribution and minimize air bubbles, which interfere with counting.

Microscopic Techniques: Precision in Practice

Start with a 40x objective to locate asci, then switch to a 100x oil-immersion lens for detailed spore counting. Systematically scan the slide in a zigzag pattern to avoid recounting. Use a mechanical stage to track coordinates and ensure comprehensive coverage. For fungi with clustered asci, employ a graticule or hemocytometer grid to estimate spore density per unit area. Digital microscopes with built-in counters can automate this process, reducing human error. Always count spores in at least 10 different asci to ensure statistical reliability.

Challenges and Solutions in Spore Counting

One common challenge is differentiating mature spores from debris or immature cells. Look for uniform size, shape, and staining intensity to confirm spore identity. In species with overlapping spores, adjust the focus slightly to visualize all layers within the ascus. For fungi with highly variable spore counts, such as *Neurospora*, consider using a phase-contrast microscope to enhance edge definition. If spore clumping occurs, dilute the sample 1:10 with distilled water and gently remix before reapplying to the slide.

Practical Tips for Consistent Results

Maintain consistent lighting and magnification settings across samples to ensure comparability. Record environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity) as these can affect spore release and ascus integrity. For longitudinal studies, use the same microscope and staining protocol to minimize variability. When working with pathogenic fungi, handle samples in a biosafety cabinet and dispose of slides in 10% bleach solution to prevent contamination. With practice, these techniques enable accurate, reproducible spore counts, essential for research and diagnostics.

Can Mold Spores Cause a Burning Sensation in Your Throat?

You may want to see also

Factors Affecting Spore Visibility

The number of spores visible per ascus under a microscope is not a fixed value but a variable influenced by several factors. Understanding these factors is crucial for accurate observation and analysis in mycology. One primary factor is the developmental stage of the ascus. In immature asci, spores may not be fully formed or visible, while in mature asci, the typical 8 spores are clearly discernible. However, overmature asci may collapse or degrade, reducing spore visibility. For optimal observation, aim to examine asci in the late mature stage, where spore walls are fully developed but the ascus structure remains intact.

Magnification and microscope quality play a pivotal role in spore visibility. A standard compound microscope with 400x to 1000x magnification is sufficient to observe individual spores within an ascus. However, lower-quality lenses or inadequate magnification may blur spore boundaries, making it difficult to count them accurately. For precise counts, use a high-resolution microscope with oil immersion and ensure proper calibration. Additionally, consider using differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy to enhance contrast and highlight spore structures, especially in transparent or lightly pigmented species.

The preparation technique significantly impacts spore visibility. Poorly prepared slides can obscure asci or damage spores, leading to inaccurate counts. To prepare an optimal slide, place a small fragment of the fungal tissue in a drop of lactic acid or water on a slide, cover with a coverslip, and apply gentle pressure to spread the tissue without crushing it. Lactic acid clears the tissue, making spores more visible, while water is suitable for less delicate samples. Avoid excessive heat or pressure, as these can distort ascus structure and reduce spore clarity.

Species-specific characteristics also affect spore visibility. Some fungi produce asci with thick walls or pigmented spores, which can obscure internal structures. For example, in *Morchella* species, the asci are often densely packed and pigmented, making individual spore counting challenging. In contrast, *Saccharomyces* species have thin-walled asci and clear spores, facilitating easy observation. Familiarize yourself with the morphology of the species you are studying to anticipate and address visibility challenges.

Environmental conditions during fungal growth can influence spore size and arrangement, further affecting visibility. Nutrient availability, humidity, and temperature impact spore development. For instance, nutrient-rich substrates may produce larger spores, while stress conditions can lead to smaller or irregularly shaped spores. To standardize observations, cultivate fungi under controlled conditions (e.g., 25°C, 70% humidity, and consistent nutrient medium) to ensure uniform spore development. This reduces variability and enhances the reliability of spore counts.

Lastly, observer skill and experience cannot be overlooked. Accurate spore counting requires practice and familiarity with fungal morphology. Beginners may struggle to distinguish spores from debris or other structures, leading to undercounting or overcounting. To improve accuracy, start with well-characterized species and compare your observations with published images or expert guidance. Over time, developing a keen eye for detail will enhance your ability to assess spore visibility and count reliably.

Root Fungus Spread: Spores vs. Roots – Which Dominates Transmission?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Species-Specific Spore Numbers per Ascus

The number of spores per ascus varies significantly across fungal species, reflecting their unique reproductive strategies and ecological niches. For instance, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, a well-studied yeast, typically produces four spores per ascus, a trait linked to its haploid-diploid life cycle. In contrast, species like *Neurospora crassa* also form eight spores per ascus, a characteristic that supports its role in genetic research. These differences are not arbitrary; they are adaptations that influence survival, dispersal, and genetic diversity. Observing these variations under a microscope requires proper staining techniques, such as using cotton blue or lactophenol cotton blue, to enhance spore visibility and ascertain accurate counts.

Analyzing species-specific spore numbers reveals insights into fungal evolution and taxonomy. For example, the genus *Aspergillus* often produces eight spores per ascus, but exceptions like *Aspergillus nidulans* with its distinctive double-layered asci highlight the complexity within a single genus. Such variations are critical for identification in mycology labs, where misidentification can lead to incorrect diagnoses or research conclusions. Microscopic examination should include noting ascus shape, size, and spore arrangement, as these features, combined with spore count, form a diagnostic fingerprint for each species.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore numbers per ascus is essential for applications in agriculture, medicine, and biotechnology. In crop protection, knowing the spore count of pathogens like *Magnaporthe oryzae* (which produces eight spores per ascus) helps in estimating disease spread and planning fungicide applications. Similarly, in pharmaceutical research, species like *Penicillium chrysogenum* (producing chains of spores rather than a fixed number per ascus) are cultivated for antibiotic production, where spore density directly impacts yield. Researchers should use hemocytometers or automated cell counters for precise quantification, especially when scaling up cultures.

Comparatively, spore numbers also reflect ecological roles. Species in nutrient-rich environments, such as *Coprinus comatus*, often produce larger asci with more spores to maximize dispersal. Conversely, fungi in harsh conditions, like *Claviceps purpurea*, may produce fewer spores per ascus but invest in hardier structures for survival. When examining these species under a microscope, adjust magnification (400x to 1000x) to balance detail and field of view, and consider using phase-contrast microscopy for unstained samples to preserve structural integrity.

In conclusion, species-specific spore numbers per ascus are a window into fungal biology, with implications ranging from taxonomy to applied science. Accurate observation requires a combination of proper staining, careful microscopy, and contextual knowledge of the species in question. Whether for research, industry, or education, mastering this aspect of mycology enhances our ability to work with fungi effectively and responsibly.

Understanding Spore Syringes: Mechanism, Uses, and Effective Application Techniques

You may want to see also

Common Errors in Spore Counting

Accurate spore counting is crucial in mycology, yet even experienced microscopists fall prey to common pitfalls. One frequent error is misinterpreting ascus structure. Asci often contain eight spores, but this isn’t universal. Some species produce fewer or more, and immature asci may appear empty or partially filled. Mistaking septa or debris for spores, or failing to account for overlapping spores in crowded asci, leads to overestimation. Always consult species-specific references to confirm expected spore counts and ascus morphology before drawing conclusions.

Another critical mistake is inadequate sample preparation. Crushing or overheating the specimen during mounting can rupture asci, releasing spores into the background and obscuring their true arrangement. Use a gentle touch when preparing slides, and opt for lower heat settings when necessary. Over-staining or under-staining can also distort spore visibility; follow protocols precisely, using recommended stain concentrations (e.g., 0.05% cotton blue in lactophenol) to ensure clarity without damage.

Human error in counting methodology further compounds inaccuracies. Relying solely on a single field of view skews results, as spore distribution within asci can vary across the sample. To mitigate this, count spores in at least 10–15 asci from different areas of the slide, then calculate the average. Automated counters or gridded slides can improve precision, but manual verification remains essential. Avoid fatigue-induced miscounts by taking breaks during prolonged sessions.

Lastly, equipment limitations often go unnoticed. Low-magnification objectives (e.g., 10x or 20x) may fail to resolve individual spores in tightly packed asci, while high magnification (e.g., 60x or 100x) can limit the field of view, making it difficult to assess the entire ascus. Use a 40x objective with a 10x eyepiece for optimal balance, and ensure proper calibration of the microscope’s stage micrometer to accurately measure spore size and arrangement. Regularly clean lenses and adjust illumination to eliminate artifacts that mimic spores.

By addressing these errors—misinterpretation of structure, poor preparation, flawed counting techniques, and equipment oversight—microscopists can significantly enhance the reliability of spore counts. Precision in this process not only aids taxonomic identification but also ensures consistency in research and diagnostic applications.

Shelf Life of Spores: How Long Do They Remain Viable?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Typically, 8 spores per ascus are visible under a microscope, as most ascomycete fungi produce asci containing 8 spores.

Yes, the number of spores per ascus can vary depending on the fungal species. While 8 spores are common, some species may produce 4, 16, or even a single spore per ascus.

Most ascomycete fungi undergo a process called octosporous development, resulting in 8 spores per ascus. This is due to two rounds of nuclear division followed by cell division, producing 8 haploid spores.