Agar, a gelatinous substance derived from seaweed, is a versatile tool in mushroom cultivation, serving as a nutrient-rich substrate for growing mycelium, the vegetative part of fungi. Widely used in both home and commercial setups, agar allows cultivators to isolate and propagate specific mushroom strains, create master cultures, and conduct experiments with precision. By combining agar with a nutrient source like malt extract or sugar, cultivators can prepare petri dishes or slants that provide a sterile environment for mycelium to thrive. This method is particularly useful for cloning mushrooms, preserving genetic purity, and avoiding contamination, making agar an essential component in the mycologist’s toolkit.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Sterile substrate for mushroom mycelium growth and isolation |

| Agar Type | Typically Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) or Malt Extract Agar (MEA) |

| Sterilization Method | Autoclaving at 121°C (250°F) for 15-30 minutes |

| Cooling | Allow agar to cool to 50-60°C (122-140°F) before use |

| Inoculation | Use sterile technique to transfer mushroom tissue or spores to agar |

| Incubation | Keep agar plates in a dark, warm (22-28°C/72-82°F) environment |

| Contamination Prevention | Work in a sterile environment, use gloves, and flame instruments |

| Mycelium Growth Time | 7-14 days depending on mushroom species |

| Transfer to Bulk Substrate | Once mycelium colonizes agar, transfer to grain or other substrate |

| Storage | Store unused agar plates at 4°C (39°F) for up to 2 weeks |

| Common Mushrooms | Oyster, Lion's Mane, Shiitake, Reishi, and others |

| Advantages | High success rate, contamination control, and genetic isolation |

| Disadvantages | Requires sterile technique, time-consuming, and initial setup cost |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Preparing Agar Medium: Sterilize agar, mix nutrients, autoclave, and cool for mushroom mycelium growth

- Inoculating Agar Plates: Use sterile technique to transfer mushroom spores or tissue to agar

- Incubating Agar Cultures: Maintain optimal temperature and humidity for mycelium colonization on agar plates

- Transferring Mycelium: Move healthy mycelium from agar to bulk substrate for fruiting

- Storing Agar Cultures: Preserve agar plates in a cool, dark place for long-term storage

Preparing Agar Medium: Sterilize agar, mix nutrients, autoclave, and cool for mushroom mycelium growth

Agar, derived from seaweed, serves as a stable, gelatinous foundation for mushroom mycelium growth, but its effectiveness hinges on proper preparation. Begin by sterilizing the agar to eliminate contaminants that could compete with or harm the mycelium. Autoclaving at 121°C (250°F) for 15–20 minutes is the gold standard, ensuring all microorganisms are eradicated. This step is non-negotiable; even a single contaminant can derail your cultivation efforts. Think of sterilization as laying a clean slate for your mycelium to thrive.

Once sterilized, the agar must be enriched with nutrients to support mycelial growth. A typical recipe includes 20–25 grams of agar powder per liter of water, supplemented with malt extract (10–20 grams), dextrose (20 grams), and optionally, vitamins or minerals. Stir until fully dissolved, ensuring no clumps remain. This nutrient-rich mixture mimics the organic matter mushrooms naturally colonize, providing the energy and building blocks for robust mycelium development. Precision in measurement is key—too little nutrient, and growth stalls; too much, and contamination risks rise.

Autoclaving the agar-nutrient mixture is the next critical step. Pour the solution into sterile containers, seal them loosely to allow steam escape, and place them in the autoclave. The high-pressure steam not only sterilizes but also ensures even distribution of nutrients. After autoclaving, let the mixture cool to around 50°C (122°F) before pouring into petri dishes or cultivation jars. Pouring too soon risks damaging the agar’s structure; too late, and it solidifies unevenly. Timing is everything here—a delicate balance between sterility and usability.

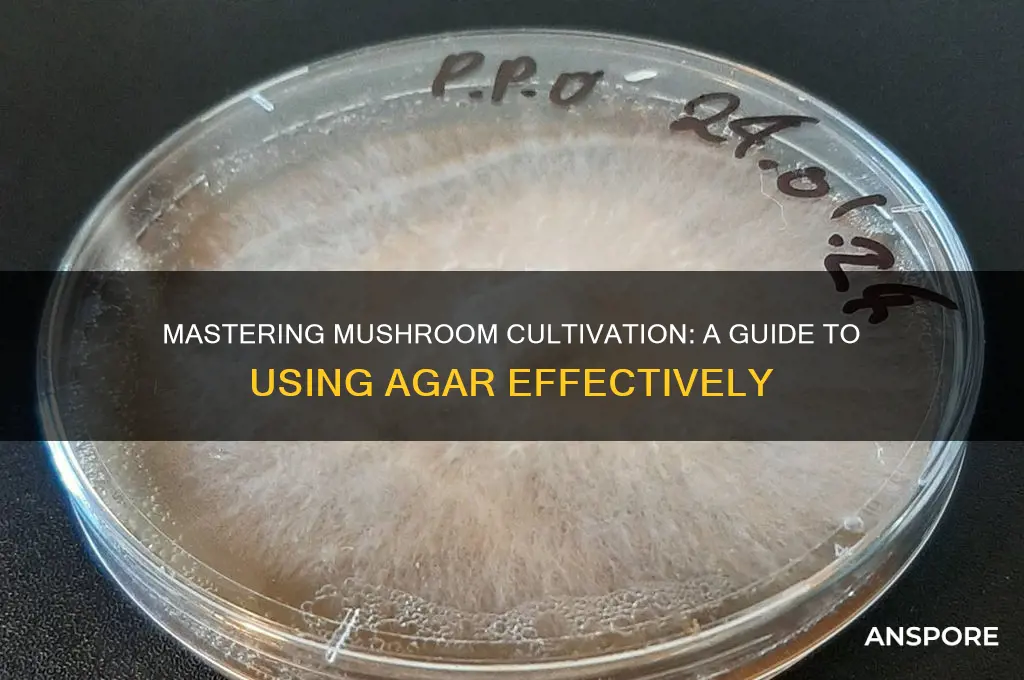

Cooling the agar medium requires patience and attention to detail. Place the containers in a clean, sterile environment, away from drafts or airborne particles. Allow the agar to solidify at room temperature, which typically takes 30–60 minutes. Once set, the medium should be clear, firm, and free of bubbles or discoloration. Any deviations signal potential issues—bubbles indicate improper mixing, while discoloration suggests contamination. A perfectly prepared agar medium is a thing of beauty, a transparent canvas ready to nurture mushroom mycelium into flourishing colonies.

In practice, this process is both art and science. Beginners often struggle with contamination, so maintaining a sterile workspace and using a laminar flow hood or still air box is highly recommended. For advanced cultivators, experimenting with nutrient ratios or adding specific supplements like gypsum can optimize growth. Regardless of skill level, the goal remains the same: creating a pristine, nutrient-rich environment where mycelium can flourish. Master this technique, and you’ll unlock the potential to cultivate a wide variety of mushroom species with precision and consistency.

Optimal Mushroom Compost Usage: Timing Tips for Healthy Garden Growth

You may want to see also

Inoculating Agar Plates: Use sterile technique to transfer mushroom spores or tissue to agar

Sterilization is paramount when inoculating agar plates with mushroom spores or tissue. Even a single contaminant can derail your entire cultivation effort. Begin by sterilizing all equipment—petri dishes, scalpels, and inoculation loops—using an autoclave or pressure cooker. Flame-sterilize your inoculation loop by passing it through a Bunsen burner flame until it glows red, allowing it to cool momentarily before use. Work in a sterile environment, such as a laminar flow hood or a still-air box, to minimize airborne contaminants. Every step must be executed with precision to ensure a clean transfer.

The inoculation process requires a steady hand and attention to detail. Start by preparing your agar plates, ensuring the agar has solidified and cooled to room temperature. Using a flame-sterilized scalpel, carefully open the petri dish, lifting the lid just enough to access the agar surface. Dip your sterilized inoculation loop into your spore solution or scrape a small piece of mushroom tissue onto the loop. Lightly streak the loop across the agar surface in a zigzag pattern, ensuring even distribution without overworking the agar. Close the dish immediately and incubate it in a dark, warm environment (around 75°F) for 7–14 days, depending on the mushroom species.

Contamination risks lurk at every step, so vigilance is key. Common contaminants include mold, bacteria, and competing fungi, which can quickly overtake your agar plate. To mitigate this, inspect your spore or tissue source for signs of contamination before inoculation. If using wild-collected material, sterilize it by rinsing with 70% isopropyl alcohol or a dilute hydrogen peroxide solution. Label each plate with the date, species, and source to track progress and identify issues early. Regularly monitor plates for unusual growth patterns or discoloration, discarding any compromised samples immediately.

Mastering agar inoculation opens doors to advanced mushroom cultivation techniques, such as tissue culture and strain isolation. By isolating specific mushroom tissues, you can propagate unique genetic traits or preserve rare species. Agar plates also serve as a diagnostic tool, allowing you to test spore viability or identify contaminants in your substrate. While the process demands precision and patience, the rewards—healthy mycelium, consistent yields, and deeper understanding of fungal biology—make it a cornerstone of successful mushroom cultivation. With practice, sterile technique becomes second nature, transforming agar inoculation from a daunting task into a rewarding skill.

Does On The Border's Queso Include Mushrooms? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Incubating Agar Cultures: Maintain optimal temperature and humidity for mycelium colonization on agar plates

Incubating agar cultures is a delicate dance of temperature and humidity, where precision fosters mycelium colonization. The ideal temperature range for most mushroom species falls between 70°F and 75°F (21°C and 24°C). Deviations above 80°F (27°C) can stress the mycelium, while temperatures below 65°F (18°C) slow growth significantly. Humidity levels must remain consistently high, ideally between 90-95%, to prevent the agar from drying out and to encourage mycelial expansion. Achieving these conditions requires a controlled environment, such as an incubation chamber or a DIY setup with a thermostat-controlled heating mat and a humidity-regulated container.

Consider the incubation process as a nurturing phase for your mycelium. Once your agar plates are inoculated, place them in a dark, undisturbed area. Use a digital hygrometer and thermometer to monitor conditions daily, adjusting as needed. For humidity control, a simple yet effective method involves placing a tray of water or a damp towel at the bottom of the incubation container. If using a heating mat, ensure it’s set to maintain the target temperature range, and avoid direct contact with the plates to prevent overheating. Patience is key; mycelium colonization on agar typically takes 7–14 days, depending on the species and environmental conditions.

While maintaining optimal temperature and humidity is crucial, avoid over-manipulating the setup. Frequent opening of the incubation container can introduce contaminants or disrupt the delicate microclimate. Instead, observe progress through the container’s transparent lid or by using a flashlight to minimize disturbance. If mold appears, isolate the affected plate immediately to prevent cross-contamination. Remember, consistency is more important than perfection; small fluctuations within the ideal range are less harmful than sudden, drastic changes.

For advanced cultivators, experimenting with slight temperature variations during incubation can yield interesting results. Some species, like *Pleurotus ostreatus* (oyster mushrooms), exhibit faster colonization at the higher end of the temperature range, while others, such as *Lentinula edodes* (shiitake), thrive in slightly cooler conditions. Documenting these nuances for each species can refine your incubation techniques over time. Ultimately, successful agar incubation hinges on creating a stable, controlled environment that mimics the mycelium’s natural habitat, fostering robust growth for subsequent stages of mushroom cultivation.

Revitalize Your Dishes: Creative Ways to Use Dried Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Transferring Mycelium: Move healthy mycelium from agar to bulk substrate for fruiting

Healthy mycelium on agar is a promising start, but it’s just the beginning. To unlock the full potential of your mushroom cultivation, you must transfer this mycelium to a bulk substrate where fruiting bodies can develop. This critical step bridges the gap between sterile lab conditions and the natural environment mushrooms thrive in.

Steps for Transferring Mycelium:

- Prepare the Bulk Substrate: Sterilize your chosen substrate (e.g., straw, wood chips, or grain) using a pressure cooker at 15 psi for 1–2 hours. Allow it to cool to room temperature in a clean environment to prevent contamination.

- Inoculate the Substrate: In a still air box or under a laminar flow hood, break the agar into small pieces and mix it thoroughly into the substrate. Aim for a 10–20% inoculation rate (e.g., 1–2 cups of agar per 10 cups of substrate).

- Incubate for Colonization: Place the inoculated substrate in a dark, warm area (70–75°F) for 2–4 weeks. Monitor for contamination and ensure even mycelial growth.

Cautions to Consider:

- Contamination Risks: Even a small spore or bacteria can outcompete your mycelium. Always work in a sterile environment and use gloves.

- Over-Inoculation: Too much agar can lead to slow colonization or nutrient depletion. Stick to recommended ratios.

- Temperature Fluctuations: Mycelium is sensitive to temperature changes. Avoid drafts or extreme conditions during incubation.

Why This Matters: Transferring mycelium to bulk substrate is where the magic happens. Agar provides a sterile starting point, but the bulk substrate offers the nutrients and space mushrooms need to fruit. Master this step, and you’ll set the stage for a bountiful harvest.

Pro Tip: For faster colonization, use a fully colonized grain spawn instead of agar. This method reduces contamination risk and speeds up the process, especially for beginners.

Should You Strain Jarred Mushrooms Before Cooking? A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

Storing Agar Cultures: Preserve agar plates in a cool, dark place for long-term storage

Agar plates are the unsung heroes of mushroom cultivation, providing a sterile environment for mycelium to thrive. However, their longevity is often overlooked. To maximize the lifespan of your agar cultures, proper storage is crucial. A cool, dark place is ideal, as it minimizes the risk of contamination and slows down the growth of unwanted microorganisms. Aim for a temperature range of 4–8°C (39–46°F), similar to a refrigerator, but avoid placing them directly in the fridge unless you’re using a dedicated lab fridge. Fluctuations in temperature and exposure to light can degrade the agar and compromise the culture, so consistency is key.

Consider the humidity levels in your storage area as well. Excess moisture can lead to condensation on the plates, creating an environment ripe for contamination. Use airtight containers or sealed plastic bags to protect the agar plates from humidity and airborne particles. For added security, include a desiccant packet in the container to absorb any excess moisture. Label each plate with the date, mushroom species, and any relevant notes to track viability over time. This simple step can save you from confusion and ensure you use the freshest cultures first.

While a cool, dark place is optimal, it’s not always feasible for long-term storage beyond a few months. For extended preservation, consider storing cultures at sub-zero temperatures, such as in a -20°C (-4°F) freezer. However, this method requires transferring the mycelium to a cryogenic medium like glycerol or sterile water before freezing. Thawing and reviving frozen cultures can be delicate, so reserve this method for when you need to store cultures for years rather than months. For most hobbyists, a cool pantry or cabinet will suffice.

One common mistake is underestimating the impact of light on agar cultures. Even ambient light can degrade the agar and stress the mycelium over time. If your storage area isn’t completely dark, wrap the plates in aluminum foil or store them in opaque containers. This small step can significantly extend the life of your cultures. Additionally, avoid stacking plates directly on top of each other, as this can lead to pressure points and potential contamination. Instead, use racks or dividers to keep them organized and spaced apart.

Finally, periodically inspect your stored agar plates for signs of contamination or degradation. Even under ideal conditions, cultures can deteriorate over time. If you notice discoloration, unusual growth, or a foul odor, discard the plate immediately to prevent cross-contamination. Aim to use stored cultures within 3–6 months for best results, though some can remain viable for up to a year with proper care. By mastering the art of storage, you’ll ensure a reliable supply of healthy agar cultures for your mushroom cultivation endeavors.

Do Mushrooms Use Chemosynthesis? Unraveling Their Unique Energy Source

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Agar is a gelatinous substance derived from seaweed, commonly used as a solidifying agent in mushroom cultivation. It provides a sterile, nutrient-rich medium for mushroom mycelium to grow and colonize before transferring to bulk substrates.

To prepare agar, mix agar powder with water and a nutrient source (like light malt extract or sugar) in a sterile container. Heat the mixture until it dissolves, sterilize it using an autoclave or pressure cooker, and then pour it into sterile Petri dishes or jars to cool and solidify.

Yes, agar is ideal for cloning mushrooms. Sterilize a small piece of mushroom tissue (e.g., gill or cap) and place it on the agar surface. The mycelium will grow from the tissue, allowing you to isolate and propagate a specific mushroom strain.

Colonization time varies by mushroom species, but it typically takes 1–4 weeks for mycelium to fully colonize agar. Factors like temperature, humidity, and sterility also influence the speed of growth.

Once the agar is fully colonized, you can transfer the mycelium to a bulk substrate (e.g., grain or sawdust) for further growth. Alternatively, you can store the agar culture in a refrigerator for future use or to preserve the strain.