Spores are often described as miniature, dormant forms of life, but are they truly mini plants? While spores share some similarities with plant seeds, such as their role in reproduction and dispersal, they are fundamentally different. Spores are produced by non-flowering plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi, as well as some bacteria and algae, and are typically unicellular or consist of a few cells. Unlike seeds, which contain an embryo and stored nutrients, spores are simpler structures that develop into new organisms under favorable conditions. This distinction raises the question: can a spore be considered a mini plant, or is it more accurate to view it as a unique reproductive mechanism in the natural world?

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A spore is a reproductive cell capable of developing into a new individual without fusion with another cell. |

| Size | Typically microscopic, ranging from 5 to 50 micrometers in diameter. |

| Structure | Simple, single-celled or multicellular, often with a protective outer wall (spore coat). |

| Function | Serves as a dispersal and survival mechanism for plants, fungi, and some bacteria. |

| Reproduction | Asexual (sporulation) in most cases, though some spores can undergo sexual reproduction. |

| Dormancy | Can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh conditions. |

| Dispersal | Dispersed by wind, water, animals, or other means to colonize new environments. |

| Comparison to Mini Plant | Not a mini plant; lacks roots, stems, leaves, and vascular tissue. It is a potential precursor to a plant under favorable conditions. |

| Organisms Producing Spores | Plants (ferns, mosses), fungi, algae, and some bacteria. |

| Development | Develops into a gametophyte (in plants) or a new organism (in fungi) upon germination. |

| Environmental Resistance | Highly resistant to desiccation, extreme temperatures, and UV radiation. |

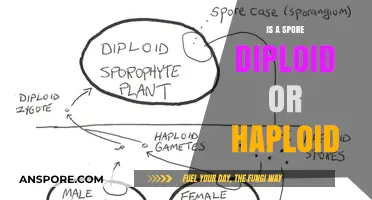

| Genetic Material | Contains a haploid nucleus (in plants) or a full set of genetic material (in fungi and bacteria). |

| Role in Ecosystem | Essential for the life cycle of spore-producing organisms and ecosystem regeneration. |

What You'll Learn

- Spore Structure: Simple, single-celled, and lightweight for dispersal, lacking plant complexity

- Germination Process: Spores develop into gametophytes, not directly into mature plants

- Role in Life Cycle: Spores are reproductive units, not miniature plants themselves

- Comparison to Seeds: Seeds contain embryos; spores are simpler, unicellular structures

- Survival Mechanisms: Spores withstand harsh conditions, while plants require immediate growth resources

Spore Structure: Simple, single-celled, and lightweight for dispersal, lacking plant complexity

Spores are nature’s masterclass in minimalism, designed for survival rather than complexity. Unlike seeds, which carry embryonic plants and nutrient stores, spores are single-celled and stripped of excess. This simplicity is their superpower: it allows them to be lightweight, easily dispersed by wind, water, or animals. For instance, a single fern can release millions of spores, each weighing mere micrograms, ensuring at least a few land in favorable conditions. This design isn’t about growth potential but about reaching the next stage of life—germination—under the right circumstances.

Consider the structure of a spore: it’s a cell encased in a protective wall, often reinforced with layers like the exine and intine in pollen grains. This wall is no accident; it’s a shield against harsh environments, from desiccation to UV radiation. For example, fungal spores can survive years in dormancy, waiting for moisture to trigger germination. Compare this to a seedling, which requires immediate resources to grow. Spores don’t need soil, water, or sunlight to persist—they need only the promise of these elements in the future.

If you’re curious how this simplicity translates to function, think of spores as biological time capsules. They lack the complexity of multicellular plants, such as roots, stems, or leaves, but this isn’t a limitation—it’s an adaptation. Their single-celled nature allows them to remain dormant for decades, even centuries, as seen in Antarctic moss spores revived after 1,500 years. This resilience makes them ideal for colonizing new or disturbed habitats, from volcanic ash to forest clearings.

Practically speaking, understanding spore structure can inform gardening, conservation, and even medicine. For gardeners, knowing that spores require specific triggers (e.g., warmth, moisture) to germinate can improve propagation success. In conservation, spore banks could preserve plant species threatened by climate change, much like seed banks. And in medicine, spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium* highlight the challenges of eradication, as their simple, durable structure resists antibiotics and heat.

The takeaway? Spores aren’t mini plants—they’re survival pods. Their simplicity and single-celled design aren’t signs of incompleteness but of evolutionary brilliance. By shedding complexity, they gain the ability to travel farther, wait longer, and endure more. In a world where survival often hinges on adaptability, spores are a lesson in doing more with less.

Are Spores Legal in Texas? Understanding the Current Laws and Regulations

You may want to see also

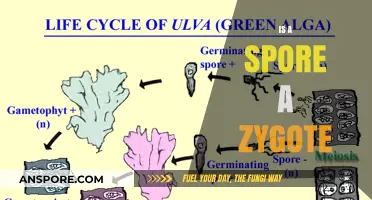

Germination Process: Spores develop into gametophytes, not directly into mature plants

Spores, often mistaken for miniature plants, are actually the starting point of a complex journey in the plant kingdom. Unlike seeds, which contain embryonic plants ready to grow, spores are single-celled structures that develop into gametophytes—a crucial but often overlooked stage in the life cycle of ferns, mosses, and other non-seed plants. This distinction is fundamental to understanding why spores are not mini plants but rather the precursors to a unique reproductive process.

Consider the germination process of a fern spore. When a spore lands in a suitable environment, it absorbs water and begins to divide, forming a tiny, heart-shaped gametophyte. This gametophyte is a self-sustaining organism with its own photosynthetic capabilities, but it is not a mature plant. Instead, it serves as the platform for sexual reproduction, producing sperm and eggs that eventually give rise to the next generation. This intermediate step highlights the spore’s role as a bridge between generations, not a condensed version of the final plant.

To illustrate, imagine a gardener attempting to grow a fern from spores. After sowing the spores on a moist substrate, they must wait patiently as the gametophytes develop over several weeks. Only when these gametophytes mature and environmental conditions trigger fertilization does the sporophyte (the familiar fern plant) begin to grow. This process underscores the spore’s function as a reproductive unit, not a miniature plant. Practical tip: Maintain high humidity and avoid direct sunlight during the gametophyte stage to ensure successful development.

Comparatively, seeds bypass this gametophyte phase entirely. In flowering plants, the embryo within the seed grows directly into a mature plant, making seeds more akin to “mini plants” than spores. This contrast reveals the evolutionary divergence between seed plants and spore-producing plants, with the latter relying on a two-step process involving distinct life forms. For educators or hobbyists, demonstrating this difference can deepen understanding of plant diversity and life cycles.

In conclusion, while spores may seem like mini plants due to their small size and potential for growth, they are fundamentally different. Their development into gametophytes, rather than directly into mature plants, is a critical aspect of their biology. Recognizing this distinction not only clarifies the role of spores but also enriches our appreciation of the intricate pathways plants use to propagate and thrive.

Mastering Spore: Tips and Tricks for Enhanced Gameplay and Creativity

You may want to see also

Role in Life Cycle: Spores are reproductive units, not miniature plants themselves

Spores are often mistaken for miniature plants, but this misconception overlooks their true purpose. Unlike seeds, which contain embryonic plants, spores are single-celled reproductive units that develop into new organisms under favorable conditions. This distinction is critical in understanding their role in the life cycle of plants, fungi, and some bacteria. For instance, fern spores, when dispersed, require specific environmental cues like moisture and warmth to germinate into tiny heart-shaped gametophytes, which then produce the next generation. This process highlights that spores are not mini plants but rather the starting point of a complex reproductive journey.

To clarify, consider the life cycle of a moss. After a spore lands in a suitable environment, it grows into a protonema, a thread-like structure that eventually develops into the gametophyte stage. This gametophyte produces eggs and sperm, which, after fertilization, grow into the sporophyte—the familiar moss plant. Here, the spore’s role is purely reproductive; it initiates the cycle but does not itself resemble a plant. This step-by-step progression underscores the spore’s function as a survival mechanism rather than a miniature organism.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this distinction is vital for horticulture and conservation. Gardeners cultivating ferns or orchids, for example, must recognize that spores require specific conditions—such as sterile substrates and controlled humidity—to develop successfully. Mistaking spores for mini plants could lead to mismanagement, such as overwatering or inadequate light, which would hinder germination. Similarly, in conservation efforts, knowing that spores are reproductive units helps in strategies like spore banking for endangered plant species, ensuring genetic diversity without confusing them with mature plant material.

A comparative analysis further illustrates the spore’s unique role. While seeds contain stored nutrients and a protective coat, spores are lightweight and resilient, often surviving harsh conditions like drought or fire. This adaptability makes them ideal for dispersal over long distances, as seen in fungal spores carried by wind or water. However, their simplicity also means they lack the immediate growth potential of seeds. This trade-off between durability and developmental complexity reinforces the idea that spores are not mini plants but specialized reproductive tools.

In conclusion, spores serve as the cornerstone of reproductive strategies in various organisms, but they are not miniature plants. Their role is to ensure survival and dispersal, initiating life cycles under precise conditions. By recognizing this, we can better appreciate their ecological significance and apply this knowledge in practical fields like gardening and conservation. The next time you encounter a spore, remember: it’s not a tiny plant but a powerful agent of renewal.

Flood Spore Survival: Understanding Longevity in Waterlogged Conditions

You may want to see also

Comparison to Seeds: Seeds contain embryos; spores are simpler, unicellular structures

Spores and seeds are both reproductive units, yet their structures and functions diverge significantly. Seeds, the hallmark of angiosperms and gymnosperms, encapsulate a plant embryo—a miniature, multicellular precursor to a new plant. This embryo, nestled within protective layers, contains the rudimentary root, shoot, and cotyledon(s), poised for germination under favorable conditions. Spores, in contrast, are unicellular and far simpler. Produced by plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi, they lack an embryo and instead rely on a single cell to initiate growth. This fundamental difference underscores their distinct evolutionary strategies and ecological roles.

Consider the process of germination. A seed’s embryo, already differentiated into distinct parts, requires only water, oxygen, and warmth to activate its pre-programmed development. For instance, a bean seed’s radicle emerges first, followed by the plumule, a process observable within 3–5 days under optimal conditions (20–25°C). Spores, however, must first divide and develop into a gametophyte—a multicellular stage that produces gametes. In ferns, this gametophyte is a heart-shaped structure called a prothallus, which can take weeks to mature. This additional step highlights the spore’s reliance on environmental cues and its less direct path to plant formation.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these differences is crucial for horticulture and conservation. Gardeners propagating ferns from spores must provide a humid, shaded environment to mimic the spore’s natural habitat, often using a sterile medium to prevent contamination. Seeds, with their robust structure, can be sown directly into soil or started in trays with minimal protection. For example, tomato seeds (Solanum lycopersicum) germinate reliably within 6–8 days when kept at 25°C, while fern spores may take 4–6 weeks to show visible growth. This disparity in handling reflects the spore’s fragility and the seed’s resilience.

Persuasively, the simplicity of spores offers evolutionary advantages in harsh environments. Their unicellular nature allows for rapid dispersal and dormancy, enabling survival in conditions where seeds might fail. For instance, fungal spores can persist in soil for years, waiting for the right moisture and temperature to activate. This adaptability makes spores indispensable in ecosystems prone to disturbance, such as fire-dependent forests or arid landscapes. Seeds, while more complex, are better suited to stable environments where resources are predictable and competition is high.

In conclusion, while both spores and seeds serve reproductive purposes, their structural and functional differences are profound. Seeds, with their embryos, represent a direct and efficient pathway to plant development, whereas spores rely on a more circuitous, environmentally dependent process. Whether you’re a gardener, ecologist, or enthusiast, recognizing these distinctions enhances your ability to cultivate, conserve, and appreciate the diversity of plant life.

Maximizing Mushroom Yield: Understanding Spores per Jar for Optimal Growth

You may want to see also

Survival Mechanisms: Spores withstand harsh conditions, while plants require immediate growth resources

Spores are nature's ultimate survivalists, capable of enduring conditions that would annihilate most life forms. Unlike plants, which require immediate access to water, sunlight, and nutrients to grow, spores enter a state of dormancy, biding their time until the environment becomes favorable. This ability to withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and even radiation is rooted in their cellular structure. Spores have thick, protective walls composed of materials like sporopollenin, which act as a shield against environmental stressors. For instance, bacterial endospores can survive boiling temperatures for hours, while fungal spores can persist in soil for decades, waiting for the right conditions to germinate.

Consider the practical implications of this survival mechanism. For gardeners, understanding spore resilience can inform strategies for controlling unwanted fungi. Fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, can remain dormant in soil or on surfaces until humidity levels rise above 70%. To prevent mold growth, maintain indoor humidity below 60% and ensure proper ventilation. Similarly, in agriculture, crop rotation disrupts the life cycle of spore-producing pathogens by denying them a consistent host, reducing the need for chemical fungicides. This knowledge transforms spore resilience from a biological curiosity into a tool for managing ecosystems.

From an evolutionary perspective, the contrast between spores and plants highlights a trade-off between endurance and immediacy. Plants invest energy in rapid growth, producing roots, stems, and leaves to compete for resources. Spores, however, prioritize longevity, sacrificing immediate development for the ability to survive in hostile environments. This strategy is particularly advantageous in unpredictable habitats, such as deserts or polar regions, where resources are scarce and conditions fluctuate drastically. For example, *Selaginella lepidophylla*, a desert plant, produces spores that can survive temperatures ranging from -20°C to 50°C, ensuring species continuity even when adult plants perish.

To harness the survival mechanisms of spores, industries are exploring their applications in biotechnology and conservation. Spores of *Bacillus subtilis*, for instance, are used in probiotics and soil remediation due to their ability to withstand harsh conditions. In conservation, scientists are banking spores of endangered plants to preserve biodiversity. By storing spores in cryogenic facilities at temperatures as low as -196°C, they can be revived centuries later, offering a hedge against extinction. This approach underscores the value of spores not just as biological curiosities, but as resources for safeguarding the future.

In contrast to the passive resilience of spores, plants rely on active growth strategies that demand immediate resources. This vulnerability makes them more susceptible to environmental changes, such as drought or nutrient depletion. However, it also allows plants to colonize stable environments rapidly, outcompeting slower-growing organisms. The dichotomy between spores and plants illustrates the diversity of survival strategies in nature, each tailored to specific ecological niches. By studying these mechanisms, we gain insights into how life adapts to Earth’s extremes, offering lessons for both biology and human innovation.

Spore Tribal Dynamics: How Parts Influence Gameplay and Strategy

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, a spore is not a mini plant. A spore is a reproductive cell produced by plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi. It can develop into a new plant under the right conditions but is not a plant itself.

A spore is a single-celled reproductive structure that can grow into a new plant without fertilization, while a seed is a multicellular structure containing an embryo, stored food, and a protective coat, requiring fertilization to develop.

Yes, spores can grow into full-sized plants, but only under specific environmental conditions, such as adequate moisture, light, and nutrients. They typically develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes to form new plants.