Spores are reproductive structures produced by various organisms, including plants, fungi, and some bacteria, and their ploidy—whether they are haploid or diploid—varies depending on the organism and its life cycle. In the context of plants, such as ferns and mosses, spores are typically haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes. These haploid spores develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes (sperm and eggs) through mitosis. When fertilization occurs, the resulting zygote is diploid, and it grows into the sporophyte generation, which produces new haploid spores through meiosis. In fungi, spores can be either haploid or diploid, depending on the species and stage of the life cycle. Understanding whether a spore is haploid is crucial for grasping the reproductive strategies and life cycles of these organisms.

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation Process: Spores develop through meiosis, ensuring they carry haploid genetic material

- Haploid vs. Diploid: Spores are haploid; gametophytes develop from them, maintaining the alternation of generations

- Fungal Spores: Most fungal spores are haploid, produced via meiosis for asexual or sexual reproduction

- Plant Spores: In plants like ferns, spores are haploid, growing into gametophytes for sexual reproduction

- Bacterial Spores: Bacterial spores are not haploid; they are dormant, diploid survival structures

Spore Formation Process: Spores develop through meiosis, ensuring they carry haploid genetic material

Spores, the resilient survival structures of many organisms, are fundamentally defined by their haploid nature. This characteristic is not a coincidence but a direct result of the spore formation process, which hinges on meiosis. Unlike mitosis, which produces genetically identical cells, meiosis involves two rounds of cell division that reduce the chromosome number by half, ensuring the resulting spores carry a single set of chromosomes. This haploid state is critical for the spore’s role in the life cycle of organisms like fungi, plants, and some protozoa, enabling genetic diversity through subsequent fertilization.

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a classic example of spore-producing plants. The sporophyte generation (diploid) produces spores via meiosis in structures called sporangia. These spores, now haploid, germinate into gametophytes, which produce gametes. When fertilization occurs, a new sporophyte is formed, completing the cycle. This process underscores the efficiency of meiosis in spore formation, ensuring that each spore is a genetically unique, haploid entity ready to contribute to the next generation.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the haploid nature of spores is essential in fields like agriculture and biotechnology. For instance, in mushroom cultivation, spores are harvested and germinated to produce mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus. Knowing that spores are haploid allows cultivators to predict genetic outcomes and select desirable traits. Similarly, in plant breeding, haploid spores from ferns or mosses can be cultured to produce homozygous lines, streamlining genetic studies and improving crop varieties.

However, the spore formation process is not without challenges. Meiosis must be precisely regulated to ensure accurate chromosome segregation, as errors can lead to inviable spores. Environmental factors, such as temperature and humidity, can also influence spore development. For example, in *Aspergillus* fungi, optimal spore formation occurs at temperatures between 25°C and 30°C, with relative humidity above 80%. Deviations from these conditions can disrupt meiosis, reducing spore viability.

In conclusion, the spore formation process is a masterpiece of biological efficiency, driven by meiosis to produce haploid spores. This mechanism not only ensures genetic diversity but also equips spores with the adaptability needed to survive harsh conditions. Whether in natural ecosystems or controlled environments, the haploid nature of spores is a cornerstone of their function, making them indispensable in both scientific research and practical applications. Understanding this process empowers us to harness the potential of spores across diverse fields, from conservation to biotechnology.

Can Spores Survive Aerobic Conditions? Exploring Their Resilience and Survival Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Haploid vs. Diploid: Spores are haploid; gametophytes develop from them, maintaining the alternation of generations

Spores, the microscopic units of life, are inherently haploid, carrying a single set of chromosomes. This fundamental characteristic distinguishes them from diploid cells, which bear two sets of chromosomes, one from each parent. In the life cycle of plants, fungi, and some algae, spores serve as the critical link between generations, ensuring the continuity of species through a process known as alternation of generations. Understanding this haploid nature is essential to grasping how organisms reproduce and adapt to their environments.

Consider the life cycle of a fern, a classic example of alternation of generations. A haploid spore germinates into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure that produces gametes (sperm and eggs). When fertilization occurs, the resulting zygote develops into a diploid sporophyte, the familiar fern plant we often see. This sporophyte then produces spores through meiosis, reducing the chromosome number back to haploid and completing the cycle. This intricate dance between haploid and diploid phases ensures genetic diversity and resilience in changing conditions.

From a practical standpoint, recognizing the haploid nature of spores has significant implications in agriculture and conservation. For instance, in crop breeding, understanding spore haploidy allows scientists to manipulate genetic traits more efficiently. By inducing sporophyte plants to produce haploid spores, breeders can quickly identify desirable traits in the gametophyte stage, reducing the time and resources required for traditional breeding methods. Similarly, in conservation efforts, preserving spore-producing species ensures the maintenance of genetic diversity, which is crucial for ecosystem stability.

Comparatively, the diploid phase in organisms like animals and humans lacks the spore-mediated alternation of generations. Instead, diploid cells directly produce haploid gametes through meiosis, leading to sexual reproduction. This contrast highlights the evolutionary adaptability of spore-producing organisms, which can thrive in diverse environments by leveraging both haploid and diploid stages. For example, fungi use spores to disperse over vast distances, colonizing new habitats and surviving harsh conditions, a strategy unavailable to strictly diploid organisms.

In conclusion, the haploid nature of spores is not merely a biological detail but a cornerstone of life’s diversity and resilience. By maintaining the alternation of generations, spores ensure genetic variation, adaptability, and survival across species. Whether in the delicate fronds of a fern or the resilient hyphae of a fungus, this haploid-diploid interplay underscores the elegance and efficiency of nature’s design. Understanding this process empowers us to innovate in agriculture, conserve biodiversity, and appreciate the intricate mechanisms that sustain life on Earth.

Do Pines Produce Spores? Unraveling the Mystery of Pine Reproduction

You may want to see also

Fungal Spores: Most fungal spores are haploid, produced via meiosis for asexual or sexual reproduction

Fungal spores, the microscopic units of dispersal and survival, are predominantly haploid, a genetic state where they carry a single set of chromosomes. This haploid nature is a cornerstone of fungal biology, enabling rapid adaptation and proliferation in diverse environments. Unlike diploid cells, which contain two sets of chromosomes, haploid spores are lighter, more resilient, and better suited for wind or water dispersal. This characteristic is essential for fungi to colonize new habitats, whether it’s a decaying log in a forest or the surface of a human nail. The haploid state also simplifies genetic recombination, allowing fungi to evolve quickly in response to environmental pressures such as antifungal agents or climate changes.

The production of these haploid spores occurs through meiosis, a specialized cell division process that reduces the chromosome number by half. Meiosis is not exclusive to sexual reproduction; in fungi, it often precedes asexual spore formation, ensuring genetic diversity even in the absence of mating. For example, in *Aspergillus* species, haploid spores called conidia are produced asexually via meiosis, allowing the fungus to spread efficiently without a mate. This dual role of meiosis—serving both sexual and asexual reproduction—highlights its evolutionary significance in fungi. By maintaining a haploid phase, fungi minimize the energy costs of producing diploid cells while maximizing their reproductive potential.

One practical implication of haploid fungal spores is their role in human health and agriculture. For instance, *Candida albicans*, a common human pathogen, alternates between haploid and diploid phases during infection, with haploid spores being more resistant to antifungal drugs. Understanding this haploid state can guide the development of targeted therapies. In agriculture, haploid spores of plant pathogens like *Fusarium* or *Botrytis* are responsible for crop losses worldwide. Farmers can mitigate this by using fungicides that disrupt spore germination or by breeding crops resistant to haploid spore invasion. Knowing the haploid nature of these spores is thus crucial for effective disease management.

Comparatively, fungal spores differ from those of plants, which are typically diploid and produced via mitosis. This distinction reflects the unique life cycles of fungi, where the haploid phase dominates. For example, in the model fungus *Neurospora crassa*, the entire life cycle is haploid except for a brief diploid zygote stage. This contrasts with plants like ferns, where the sporophyte (diploid) phase is more prominent. Such comparisons underscore the evolutionary flexibility of fungi, which have harnessed the haploid state to thrive in nearly every ecosystem on Earth.

In conclusion, the haploid nature of most fungal spores is a key to their success, enabling efficient dispersal, genetic diversity, and adaptability. Whether produced sexually or asexually, these spores are the result of meiosis, a process that ensures their lightweight, resilient structure. From medical challenges to agricultural threats, understanding this haploid state offers practical insights for combating fungal diseases. By focusing on the unique biology of fungal spores, researchers and practitioners can develop more effective strategies to manage these ubiquitous organisms.

Mastering Spore Syringe Techniques: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners

You may want to see also

Plant Spores: In plants like ferns, spores are haploid, growing into gametophytes for sexual reproduction

In the life cycle of plants like ferns, spores play a pivotal role as the starting point for a new generation. These spores are haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes, a genetic blueprint that is half the number found in the parent plant. This haploid nature is crucial because it sets the stage for sexual reproduction, a process that reintroduces genetic diversity. When a spore germinates, it grows into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure that produces gametes—sperm and eggs. This gametophyte is the sexual phase of the fern's life cycle, where the fusion of gametes will eventually restore the diploid condition in the next generation.

Consider the practical implications of this process for gardeners or botanists. If you’re cultivating ferns, understanding that spores are haploid can guide your propagation efforts. Spores are incredibly lightweight and disperse easily, often carried by wind or water. To collect them, place a mature fern frond on a sheet of paper for a few days, allowing the spores to drop naturally. Once collected, sow the spores on a sterile medium like peat moss or vermiculite, keeping the environment humid and warm (around 70–75°F). Within a few weeks, you’ll observe tiny gametophytes emerging, signaling the beginning of a new fern’s life cycle.

From an evolutionary perspective, the haploid nature of spores in ferns and other plants is a testament to the efficiency of their reproductive strategy. Unlike seed-producing plants, which invest energy in protecting and nourishing embryos, spore-producing plants rely on sheer numbers and adaptability. A single fern can release thousands of spores, increasing the likelihood that some will land in favorable conditions. This strategy, combined with the haploid-diploid alternation of generations, ensures genetic diversity and resilience in changing environments. For instance, ferns have thrived for over 360 million years, surviving mass extinctions and adapting to diverse habitats, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrast between spore-producing plants like ferns and seed-producing plants like angiosperms. While both rely on alternation of generations, the haploid phase in ferns is free-living and independent, whereas in seed plants, it is highly reduced and dependent on the parent. This difference underscores the evolutionary trade-offs between investing in individual spores or seeds. For educators or students, this comparison offers a rich opportunity to explore the diversity of plant reproduction and its ecological implications. By examining both systems, one gains a deeper appreciation for the ingenuity of nature’s solutions to the challenge of perpetuating life.

Finally, for those interested in conservation or restoration ecology, understanding the haploid nature of plant spores is essential. Ferns and other spore-producing plants often play critical roles in ecosystem recovery, particularly in disturbed or shaded environments. Their ability to colonize bare soil quickly makes them pioneers in succession processes. When planning reforestation or habitat restoration projects, incorporating spore-producing species can enhance soil stability and biodiversity. Practical tips include using local spore sources to ensure genetic compatibility and creating microhabitats that mimic natural conditions, such as maintaining high humidity and partial shade during the early stages of gametophyte development. This knowledge not only aids in conservation efforts but also deepens our connection to the intricate web of life that sustains our planet.

Mushroom Spore Release: Unveiling the Astonishing Quantity and Impact

You may want to see also

Bacterial Spores: Bacterial spores are not haploid; they are dormant, diploid survival structures

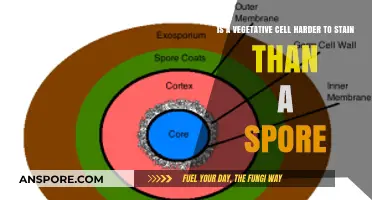

Bacterial spores defy the haploid assumption often associated with spores in general. Unlike fungal or plant spores, which are typically haploid (containing a single set of chromosomes), bacterial spores are diploid, retaining the full genetic complement of the parent cell. This distinction is crucial for understanding their role as survival structures. When environmental conditions turn harsh—extreme temperatures, desiccation, or chemical exposure—bacterial cells like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* form spores to endure. These spores are not reproductive units but rather protective shells housing the bacterium’s DNA and essential enzymes. Their diploid nature ensures genetic stability during dormancy, allowing the spore to revive and resume growth once conditions improve.

Consider the process of sporulation as a meticulous survival strategy. It begins with DNA replication, followed by the formation of a protective endospore within the mother cell. This endospore is encased in multiple layers, including a cortex rich in peptidoglycan and a proteinaceous coat, which provide resistance to heat, radiation, and chemicals. Notably, the spore’s diploid state is maintained throughout this process, ensuring that upon germination, the emerging bacterium retains its full genetic potential. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis* spores can survive in soil for decades, only to germinate and cause anthrax when ingested by a host. This resilience underscores the importance of their diploid structure in long-term survival.

From a practical standpoint, understanding bacterial spores’ diploid nature is vital for industries like food safety and healthcare. Spores of *Clostridium botulinum*, for example, can survive boiling temperatures (100°C) for hours, making them a significant concern in canned foods. To eliminate such spores, food manufacturers employ sterilization techniques like autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes, depending on the product. Similarly, in medical settings, spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridioides difficile* pose challenges due to their resistance to standard disinfectants. Using spore-specific disinfectants, such as chlorine bleach (5,000–10,000 ppm), is essential for infection control. These measures highlight the need to target the spore’s robust, diploid structure to ensure effective eradication.

Comparatively, the diploid nature of bacterial spores contrasts sharply with haploid fungal spores, which serve primarily reproductive functions. While fungal spores disperse to colonize new environments, bacterial spores focus on endurance. This difference reflects their evolutionary strategies: fungi prioritize proliferation, whereas bacteria prioritize persistence. For instance, fungal spores like those of *Aspergillus* are haploid and germinate quickly in favorable conditions, whereas bacterial spores can remain dormant for years, waiting for optimal conditions. This comparison emphasizes the unique role of bacterial spores as diploid survival structures, rather than agents of immediate reproduction.

In conclusion, bacterial spores are not haploid but diploid, a trait central to their function as survival mechanisms. Their ability to withstand extreme conditions relies on this genetic completeness, coupled with a multi-layered protective structure. Whether in food preservation, medical disinfection, or environmental microbiology, recognizing this diploid nature is key to managing spore-forming bacteria effectively. By targeting their unique biology, we can develop strategies to control or eliminate them, ensuring safety in various contexts. Thus, bacterial spores serve as a testament to the ingenuity of microbial survival, rooted in their diploid, dormant design.

Are Spore-Grown Plants Harmful? Unveiling the Truth About Their Safety

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spores are typically haploid, meaning they contain half the number of chromosomes found in the parent organism.

Spores are produced through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid cells.

Most spores, such as those in fungi, plants (e.g., ferns and mosses), and some bacteria, are haploid. However, there are exceptions, like certain bacterial endospores, which are not involved in sexual reproduction and remain diploid.

Haploid spores are crucial for sexual reproduction in many organisms, as they can fuse with another haploid cell (gamete) to form a diploid zygote, restoring the full chromosome set for the next generation.