The question of whether a spore is a virus or a mould stems from the diverse nature of microorganisms and their reproductive strategies. Spores are actually neither viruses nor moulds but rather a dormant, resilient form of certain bacteria, fungi, plants, and some protozoa, designed to survive harsh conditions. Moulds, on the other hand, are a type of fungus that grows in multicellular, thread-like structures called hyphae, often visible as fuzzy patches on organic matter. Viruses are entirely different, being microscopic infectious agents that require a host to replicate and lack the cellular structure of living organisms. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for grasping the roles these entities play in ecosystems, health, and various industries.

What You'll Learn

Spore vs. Virus: Key Differences

Spores and viruses, though both microscopic entities, differ fundamentally in their nature, structure, and behavior. Spores are dormant, highly resistant reproductive units produced by certain bacteria, fungi, and plants. They are designed to survive harsh conditions—extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemicals—until they find a suitable environment to germinate and grow. Viruses, on the other hand, are obligate intracellular parasites. They lack cellular structure, consisting only of genetic material (DNA or RNA) encased in a protein coat. Viruses cannot replicate independently; they hijack host cells to multiply, often causing disease in the process. This distinction in survival strategy and dependency on a host underscores their contrasting roles in biology.

Consider the practical implications of these differences. Spores, such as those from *Bacillus anthracis* (the causative agent of anthrax), can remain viable in soil for decades, posing long-term risks in contaminated environments. To neutralize spores, extreme measures are required—autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes or exposure to strong disinfectants like bleach. Viruses, however, are more fragile outside a host. For instance, influenza viruses can survive on surfaces for only 24–48 hours, and they are easily inactivated by alcohol-based hand sanitizers (at least 60% alcohol) or soap and water. Understanding these vulnerabilities is critical for effective disinfection protocols in healthcare and everyday settings.

From a health perspective, the mechanisms of infection further highlight the spore-virus divide. Spores, once inhaled or ingested, germinate into active cells that multiply and produce toxins, as seen in botulism caused by *Clostridium botulinum*. Treatment often involves antibiotics and antitoxins. Viruses, however, insert their genetic material into host cells, disrupting normal functions. Antibiotics are ineffective against viruses; antiviral medications like oseltamivir (for influenza) target viral replication, while vaccines prevent infection by priming the immune system. For example, the COVID-19 vaccine trains the body to recognize and neutralize SARS-CoV-2, a virus, whereas no vaccine exists for fungal spores like *Aspergillus*, which cause infections in immunocompromised individuals.

A comparative analysis reveals that spores and viruses also differ in their ecological roles. Spores are essential for the survival and dispersal of organisms like mushrooms and ferns, contributing to biodiversity and nutrient cycling in ecosystems. Viruses, while often pathogenic, play a dual role—they regulate populations by infecting bacteria (as seen with bacteriophages) and drive genetic diversity through horizontal gene transfer. For instance, 8% of the human genome consists of endogenous retroviruses, remnants of ancient viral infections. This duality contrasts with spores, which are primarily reproductive tools rather than agents of genetic exchange.

In summary, spores and viruses diverge in structure, survival mechanisms, and impact. Spores are resilient, self-sufficient units that ensure species continuity, while viruses are dependent parasites that exploit hosts for replication. Recognizing these differences informs strategies for disinfection, treatment, and ecological understanding. Whether addressing a fungal outbreak in agriculture or a viral pandemic, tailored approaches rooted in these distinctions are essential for effective management.

Hand Sanitizer vs. C. Diff Spores: Does It Really Kill Them?

You may want to see also

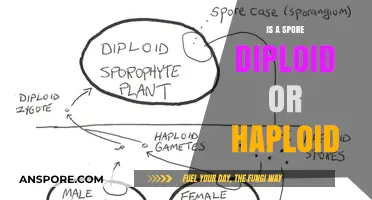

Spore vs. Mould: Structural Variances

Spores and moulds, though often conflated, exhibit distinct structural differences that define their roles in nature. Spores are reproductive units produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, designed for dispersal and survival in harsh conditions. They are typically unicellular, encased in a protective outer layer called a spore wall, which shields them from desiccation, radiation, and predators. Moulds, on the other hand, are multicellular fungi composed of thread-like structures called hyphae, which collectively form a mycelium. This mycelium is the vegetative part of the fungus, responsible for nutrient absorption and growth. Structurally, spores are dormant and singular, while moulds are active, growing entities.

To illustrate, consider the lifecycle of a common mould like *Aspergillus*. When conditions are favorable, the mycelium produces spore-bearing structures called conidiophores, which release spores into the environment. These spores are not moulds themselves but rather the means by which moulds propagate. Once a spore lands in a suitable environment, it germinates, forming new hyphae and eventually a mycelium. This distinction is critical: spores are the dispersal agents, while moulds are the living, growing organisms. For practical purposes, understanding this difference is essential in fields like food safety, where spore contamination (e.g., from *Bacillus cereus*) requires different handling than mould growth (e.g., *Penicillium*).

From a structural perspective, the spore’s protective wall is its defining feature. Composed of layers like the exosporium, spore coat, and cortex, it provides resilience against extreme temperatures, chemicals, and UV radiation. For example, bacterial endospores can survive boiling water for hours, making them a challenge in sterilization processes. Moulds lack such a protective structure; their hyphae are vulnerable to environmental stressors, relying instead on rapid growth and nutrient acquisition. This vulnerability is why moulds thrive in damp, nutrient-rich environments but perish quickly in dry or hostile conditions.

A comparative analysis reveals that spores are nature’s survival capsules, optimized for endurance and dispersal, while moulds are growth machines, adapted for resource exploitation. For instance, in agriculture, spore-forming pathogens like *Claviceps purpurea* (ergot fungus) can persist in soil for years, waiting for optimal conditions to infect crops. Moulds like *Fusarium*, however, require immediate access to nutrients and moisture to establish themselves. This structural variance dictates their control strategies: spores may require heat treatment or chemical sterilants, while moulds are often managed through humidity control and physical removal.

In practical terms, distinguishing between spores and moulds is crucial for effective management. For homeowners dealing with mould, reducing indoor humidity below 60% and promptly drying wet materials can prevent mycelial growth. In contrast, eliminating spore-forming bacteria from surfaces may necessitate autoclaving (121°C for 15–20 minutes) or using spore-specific disinfectants like hydrogen peroxide or chlorine bleach. Understanding these structural differences not only clarifies their biological roles but also informs targeted interventions, ensuring both safety and efficiency.

Mastering Fungal Spore Collection: Techniques for Successful Harvesting

You may want to see also

Are Spores Harmful to Humans?

Spores are not viruses or molds; they are reproductive structures produced by certain bacteria, fungi, and plants. Unlike viruses, which require living hosts to replicate, and molds, which are multicellular fungi, spores are dormant, resilient forms designed to survive harsh conditions. This distinction is crucial when assessing their potential harm to humans.

While most spores are harmless, some can pose health risks under specific conditions. For instance, fungal spores like those from *Aspergillus* or *Stachybotrys* (black mold) can trigger allergic reactions, asthma, or infections in immunocompromised individuals. Bacterial spores, such as those from *Clostridium botulinum* or *Bacillus anthracis*, can cause severe illnesses like botulism or anthrax if ingested or inhaled. However, exposure alone is not always dangerous; it’s the dose, duration, and individual susceptibility that determine harm. For example, inhaling a few mold spores in a well-ventilated area is unlikely to cause issues, but prolonged exposure in damp environments can lead to respiratory problems.

To minimize risks, practical steps include maintaining indoor humidity below 60%, promptly fixing water leaks, and using air purifiers with HEPA filters. For those with allergies or weakened immune systems, wearing masks during outdoor activities in spore-heavy seasons (like fall) can be beneficial. Additionally, proper food storage and handling are critical to prevent bacterial spore contamination, as temperatures above 75°C (167°F) are needed to destroy them effectively.

Comparatively, while viruses and molds are often immediate concerns, spores’ harm is more insidious, requiring specific conditions to activate. Unlike viruses, which spread rapidly, spores rely on environmental factors like moisture and warmth to germinate. Unlike molds, which grow visibly, spores remain invisible until they colonize. This makes prevention—through environmental control and awareness—key to avoiding spore-related health issues.

In conclusion, spores are neither viruses nor molds but can be harmful under certain circumstances. Understanding their nature, potential risks, and preventive measures empowers individuals to protect themselves effectively. Whether in homes, workplaces, or outdoor settings, proactive steps can mitigate spore-related health threats, ensuring a safer environment for all.

Mobile Genetic Elements: Can They Integrate into C. difficile Spore Genomes?

You may want to see also

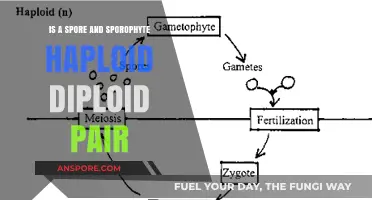

Virus, Mould, or Spore: Reproduction Methods

Spores, viruses, and moulds are often conflated, yet their reproductive strategies reveal distinct identities. Spores, produced by fungi, plants, and some bacteria, are resilient, dormant structures designed to survive harsh conditions. They reproduce through sporulation, a process where a parent organism releases spores that germinate under favorable conditions, growing into new individuals. Mould, a type of fungus, reproduces via hyphal growth and spore dispersal, spreading through lightweight, airborne spores that colonize new surfaces. Viruses, however, lack cellular structure and reproduce by hijacking host cells, injecting their genetic material to force the cell to produce viral copies. Understanding these methods clarifies why spores are neither viruses nor mould but a survival mechanism used by diverse organisms.

Consider the practical implications of these reproductive methods. Mould spores, for instance, thrive in damp environments, making bathrooms and basements prime breeding grounds. To control mould, maintain humidity below 60% and ventilate areas prone to moisture. Spores from plants, like those of ferns or mushrooms, require specific triggers—light, water, or temperature—to germinate, making them less invasive but highly adaptable. Viruses, on the other hand, demand direct intervention: disinfectants like 70% isopropyl alcohol or bleach solutions (1:10 dilution) can inactivate many viruses on surfaces, but preventing transmission relies on barriers like masks and vaccines. Each reproductive strategy dictates unique management approaches, emphasizing the importance of targeted solutions.

A comparative analysis highlights the efficiency of these methods. Viral replication is rapid but dependent on hosts, limiting their survival outside living organisms. Mould spores are prolific, with a single colony releasing millions of spores daily, ensuring widespread dispersal. Spores, however, prioritize longevity over immediacy, remaining dormant for years until conditions are ideal. This contrasts with viruses, which degrade quickly without a host, and mould, which requires ongoing moisture to sustain growth. For example, fungal spores in soil can persist for decades, while influenza viruses on surfaces typically remain infectious for only 24–48 hours. Such differences underscore why spores are a survival tool, not a pathogen like viruses or a colonizer like mould.

To illustrate, imagine a scenario where a basement floods. Mould spores, already present in the air, land on damp surfaces and begin hyphal growth within 24–48 hours, forming visible colonies. Meanwhile, bacterial spores in the soil, activated by moisture, germinate to repair damaged ecosystems. Viruses, absent a host, would remain inactive or degrade. This example demonstrates how reproductive methods dictate ecological roles: mould as a decomposer, spores as survivors, and viruses as obligate parasites. Recognizing these distinctions not only clarifies their identities but also informs effective control strategies, whether through dehumidifiers, sterilization, or antiviral measures.

Do Pistils Release Spores? Unraveling the Mystery of Plant Reproduction

You may want to see also

Where Do Spores Come From?

Spores are not viruses or molds; they are reproductive units produced by certain plants, fungi, and bacteria. Understanding their origin requires a dive into the biological mechanisms of these organisms. Plants like ferns release spores through sporangia, often located on the underside of leaves. Fungi, such as mushrooms, disperse spores via gills or pores, while bacteria form endospores as a survival strategy. Each method is tailored to the organism’s environment, ensuring spores can travel and germinate under favorable conditions.

Consider the lifecycle of a fungus, a primary spore producer. When a mushroom matures, it releases billions of spores into the air, each capable of growing into a new organism if it lands in a suitable habitat. This process, called sporulation, is triggered by environmental cues like humidity or nutrient availability. Unlike viruses, which require hosts to replicate, spores are self-contained units designed for dispersal and survival. Similarly, bacterial endospores can withstand extreme conditions, from heat to radiation, making them distinct from both viruses and molds.

To observe spores firsthand, try this simple experiment: Place a mature mushroom gill-side down on a piece of paper for 24 hours. The spores will drop, creating a visible pattern. This demonstrates their passive dispersal method, relying on air currents or gravity. In contrast, plant spores often require wind or water for transport. For instance, fern spores are lightweight and easily carried by breezes, while bacterial endospores may attach to surfaces or organisms for relocation.

Practical knowledge of spore origins can inform strategies to control their spread. In homes, mold spores thrive in damp areas like bathrooms or basements. Reducing humidity below 60% and fixing leaks can inhibit their growth. For gardeners, understanding plant spore dispersal helps optimize conditions for ferns or mosses. Bacterial spores, though resilient, can be neutralized by boiling water for 10–15 minutes or using autoclaves in lab settings. Each approach targets the unique biology of spore-producing organisms.

Ultimately, spores originate from specialized structures in plants, fungi, and bacteria, each adapted to their ecological niche. Their production is a survival mechanism, not a pathogenic process like viruses or a colonial growth like molds. By recognizing these distinctions, we can better manage their presence in environments, from homes to laboratories. Whether you’re a gardener, homeowner, or scientist, understanding spore origins empowers practical and informed decision-making.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: Growing Spawn from Spore Prints

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, a spore is not a virus. Spores are reproductive structures produced by certain organisms like fungi, plants, and bacteria, while viruses are microscopic infectious agents that require a host to replicate.

A spore is not mould itself but can develop into mould under the right conditions. Mould is a type of fungus, and spores are the reproductive units that allow mould to spread and grow.

No, spores and viruses are unrelated. Spores are living cells or structures that can grow into new organisms, whereas viruses are non-living particles that infect host cells to replicate.

Spores can cause infections in certain cases, such as fungal infections, but they function differently from viruses. Viruses invade host cells to replicate, while spores can germinate and grow into organisms that may cause harm.

Mould spores can be harmful, especially to individuals with allergies or weakened immune systems, but they are not the same as viruses. Mould spores can trigger respiratory issues, while viruses cause infectious diseases by invading host cells.