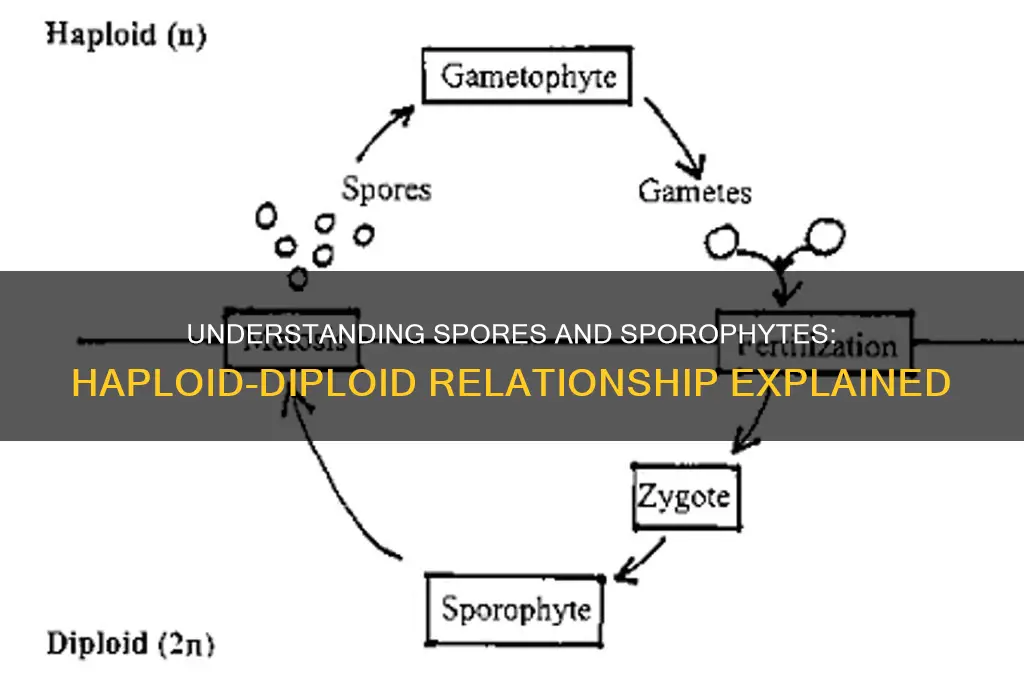

The relationship between a spore and a sporophyte is a fundamental concept in the life cycles of plants, particularly in bryophytes, ferns, and seed plants. In this context, the spore is typically a haploid cell, meaning it contains a single set of chromosomes. When a spore germinates, it develops into a gametophyte, which produces gametes (sperm and egg cells). In contrast, the sporophyte is the diploid stage of the life cycle, containing two sets of chromosomes. The sporophyte produces spores through a process called meiosis, which reduces the chromosome number from diploid to haploid. This alternation between haploid and diploid phases, known as the alternation of generations, is a hallmark of plant life cycles, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability. Understanding this relationship is crucial for grasping the reproductive strategies and evolutionary success of various plant groups.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spore | Haploid (n) |

| Sporophyte | Diploid (2n) |

| Origin | Spores are produced by the sporophyte through meiosis. |

| Function | Spores develop into gametophytes, which produce gametes. |

| Life Cycle | Part of the alternation of generations in plants (e.g., ferns, mosses, and seed plants). |

| Structure | Single-celled or multicellular, often with protective walls. |

| Development | Spores germinate into gametophytes, which are haploid. |

| Example | Fern spores grow into small, heart-shaped gametophytes. |

| Sporophyte | Develops from the fusion of gametes (fertilization) and is diploid. |

| Role | Produces spores via meiosis, completing the life cycle. |

| Example | The leafy, vascular plant in ferns is the sporophyte. |

| Genetic Composition | Spore (n) vs. Sporophyte (2n) reflects haploid and diploid phases. |

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation: Spores develop from haploid cells via meiosis in sporangia of parent sporophyte plants

- Sporophyte Development: Diploid sporophyte grows from zygote formed by haploid gamete fusion during fertilization

- Alternation of Generations: Haploid gametophyte and diploid sporophyte phases alternate in plant life cycles

- Haploid Gametophyte Role: Produces gametes (sperm, eggs) for sexual reproduction in the plant life cycle

- Diploid Sporophyte Function: Generates spores through meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity in offspring

Spore Formation: Spores develop from haploid cells via meiosis in sporangia of parent sporophyte plants

Spores are the unsung heroes of plant reproduction, particularly in the life cycles of ferns, mosses, and fungi. These microscopic structures are not just dormant survival pods; they are the product of a precise biological process that ensures genetic diversity and species continuity. At the heart of spore formation lies meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, creating haploid cells. This process occurs within specialized structures called sporangia, which are housed on the parent sporophyte plant. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for anyone studying plant biology or cultivating spore-producing species.

Consider the sporophyte, the dominant phase in the life cycles of many plants, which is diploid, meaning it carries two sets of chromosomes. Within its sporangia, haploid spores are generated through meiosis, a step that introduces genetic variation by shuffling and recombining genetic material. This diversity is essential for adaptation and survival in changing environments. For instance, in ferns, the sporophyte produces sporangia on the undersides of its fronds, where spores develop and are eventually released. Gardeners cultivating ferns should note that maintaining humidity around the plant can enhance spore viability, as dry conditions may hinder their dispersal and germination.

The formation of spores is a delicate balance of timing and environmental conditions. Meiosis must occur under optimal circumstances to ensure the spores are viable. For example, in mosses, sporangia are often elevated on stalks to aid in spore dispersal by wind. Hobbyists growing mosses in terrariums should mimic natural conditions by providing adequate airflow and avoiding overcrowding, as stagnant air can trap spores and prevent their spread. Additionally, temperature plays a critical role; most spore-producing plants thrive in temperatures between 60°F and 75°F (15°C to 24°C), with fluctuations encouraging sporulation in some species.

From a comparative perspective, spore formation in fungi differs slightly but shares the same foundational principle of meiosis. Fungal sporangia release spores that can travel vast distances, colonizing new habitats. This adaptability is why fungi are found in nearly every ecosystem on Earth. For those experimenting with mushroom cultivation, maintaining sterile conditions during spore inoculation is paramount, as contamination can derail the entire process. Using a laminar flow hood or a DIY setup with a HEPA filter can significantly improve success rates.

In conclusion, spore formation is a testament to nature’s ingenuity, blending precision and adaptability. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or enthusiast, understanding the role of meiosis in sporangia provides actionable insights for nurturing spore-producing plants. By replicating their natural conditions and respecting their biological rhythms, you can foster thriving ecosystems, whether in a forest or a terrarium. This knowledge not only deepens appreciation for plant life cycles but also empowers practical applications in horticulture and conservation.

Mastering Spore: Crafting Complex and Advanced Creatures Step-by-Step

You may want to see also

Sporophyte Development: Diploid sporophyte grows from zygote formed by haploid gamete fusion during fertilization

The fusion of haploid gametes during fertilization marks the inception of sporophyte development, a process fundamental to the life cycles of plants and certain algae. This union results in a diploid zygote, which serves as the foundational cell for the sporophyte generation. Unlike the haploid phase, which is often associated with spores and gametophytes, the sporophyte phase is characterized by its diploid nature, reflecting the combined genetic material from two parent gametes. This developmental stage is crucial for the organism's ability to thrive in diverse environments, as it allows for greater genetic complexity and adaptability.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern as an illustrative example. Following fertilization, the zygote undergoes mitotic divisions, giving rise to the embryonic sporophyte. This embryo develops within the protective confines of the gametophyte, which provides essential nutrients and support during the early stages of growth. As the sporophyte matures, it eventually emerges as an independent plant, capable of photosynthesis and resource acquisition. The transition from zygote to mature sporophyte is a testament to the intricate coordination of cellular processes, ensuring the successful establishment of the diploid phase.

From an analytical perspective, sporophyte development highlights the evolutionary advantages of the alternation of generations. This lifecycle strategy, common in plants and some algae, alternates between haploid and diploid phases, each with distinct roles. The sporophyte phase, being diploid, is better equipped to withstand environmental stresses due to its genetic diversity. For instance, in angiosperms (flowering plants), the sporophyte generation dominates the lifecycle, with the haploid phase reduced to microscopic gametophytes. This shift underscores the importance of the sporophyte in ensuring species survival and reproductive success.

Practical insights into sporophyte development can inform agricultural and horticultural practices. For example, understanding the nutrient requirements of the developing sporophyte can optimize fertilization techniques in crop plants. In tissue culture, manipulating environmental conditions such as light, temperature, and humidity can enhance sporophyte growth from zygotes. For hobbyists cultivating ferns or mosses, providing adequate moisture and shade during the early sporophyte stages can significantly improve survival rates. These applications demonstrate the tangible benefits of comprehending sporophyte development in both scientific and practical contexts.

In conclusion, sporophyte development exemplifies the transformative journey from a single diploid zygote to a complex, multicellular organism. This process is not merely a biological curiosity but a cornerstone of plant and algal lifecycles, with profound implications for ecology, agriculture, and conservation. By dissecting the mechanisms and significance of sporophyte growth, we gain valuable insights into the resilience and diversity of life on Earth. Whether in the lab, the field, or the garden, appreciating this developmental phase enriches our understanding of the natural world and our ability to interact with it sustainably.

Mastering Spore: A Step-by-Step Guide to Installing the Epic Mod

You may want to see also

Alternation of Generations: Haploid gametophyte and diploid sporophyte phases alternate in plant life cycles

In the intricate dance of plant reproduction, the alternation of generations stands as a cornerstone, a cyclical process where haploid gametophytes and diploid sporophytes take turns dominating the life cycle. This phenomenon is not merely a biological curiosity but a strategic adaptation that ensures genetic diversity and survival across varying environments. For instance, in ferns, the visible plant we often see is the sporophyte generation, which produces spores through structures called sporangia. These spores, being haploid, develop into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes that are often hidden from plain sight, yet they play a crucial role in the next phase of reproduction.

Consider the practical implications of this alternation in horticulture. Gardeners cultivating mosses, which are predominantly gametophytes, must understand that the green, carpet-like structures they nurture are haploid. To propagate these plants, one must either allow them to produce gametes and undergo fertilization or rely on fragmentation, a form of asexual reproduction. In contrast, when dealing with seed-producing plants like angiosperms, the focus shifts to the sporophyte phase, where seeds are the result of a complex interplay between haploid gametophytes (pollen and embryo sacs) and the diploid parent plant. This knowledge informs techniques such as seed collection and sowing, ensuring that the next generation of plants thrives.

From an evolutionary perspective, the alternation of generations is a testament to the ingenuity of nature. By alternating between haploid and diploid phases, plants maximize their adaptability. Haploid gametophytes, being more susceptible to environmental stresses due to their single set of chromosomes, are typically short-lived and focused on reproduction. Diploid sporophytes, with their greater genetic stability, invest in growth and resource accumulation. This division of labor allows plants to exploit different ecological niches, from the damp, shaded habitats favored by fern gametophytes to the sunlit canopies dominated by sporophytes.

A comparative analysis reveals the diversity in how different plant groups execute this alternation. In bryophytes, such as liverworts and mosses, the gametophyte is the more prominent and long-lived phase, while the sporophyte remains dependent on it. In contrast, vascular plants like ferns and seed plants invert this relationship, with the sporophyte taking center stage. This variation underscores the flexibility of the alternation of generations as a reproductive strategy, tailored to the specific needs and environments of each plant group.

For educators and students, understanding this concept opens doors to deeper exploration of botany. A hands-on activity could involve observing the life cycles of mosses and ferns side by side, highlighting the differences in their dominant phases. For instance, placing a fern spore on a damp substrate and monitoring its development into a gametophyte, followed by fertilization and the emergence of a new sporophyte, provides a tangible demonstration of the alternation. Similarly, examining the microscopic structure of an angiosperm ovule can reveal the hidden gametophyte within, bridging the gap between theory and practice. This approach not only reinforces learning but also fosters an appreciation for the complexity and beauty of plant life cycles.

Install and Play Spore on Windows 10: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Haploid Gametophyte Role: Produces gametes (sperm, eggs) for sexual reproduction in the plant life cycle

In the intricate dance of plant reproduction, the haploid gametophyte plays a pivotal role as the gamete factory. This diminutive, often overlooked phase of the plant life cycle is responsible for producing the sperm and eggs necessary for sexual reproduction. Unlike the more robust sporophyte generation, the gametophyte is a delicate, short-lived structure, yet its function is indispensable. In ferns, for instance, the gametophyte is a small, heart-shaped organism that grows independently in moist environments, developing both male and female reproductive organs on its surface. This dual capability underscores its efficiency in ensuring the continuation of the species.

Consider the process in angiosperms, where the gametophyte is highly reduced but no less critical. The male gametophyte, or pollen grain, consists of just three cells: one vegetative cell and two sperm cells. Upon landing on the stigma of a flower, the pollen grain germinates, producing a pollen tube that delivers the sperm to the ovule. The female gametophyte, or embryo sac, is equally specialized, containing seven cells, including one egg cell. This precision in structure and function highlights the gametophyte’s role as a finely tuned reproductive machine, optimized for the sole purpose of producing and delivering gametes.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the gametophyte’s role is essential for horticulture and agriculture. For example, in seed production, ensuring optimal conditions for gametophyte development—such as adequate moisture for ferns or proper pollination in flowering plants—can significantly impact yield. In tissue culture, scientists often manipulate gametophytes to produce haploid plants, which are then doubled to create homozygous lines, reducing the time required for traditional breeding. This technique is particularly valuable in crops like wheat and rice, where rapid genetic improvement is crucial for food security.

Comparatively, the gametophyte’s role in plants contrasts sharply with that in animals, where gametes are produced directly by diploid organisms. This distinction reflects the alternation of generations in plants, a unique evolutionary strategy that balances genetic diversity and stability. While the sporophyte dominates in size and longevity, the gametophyte’s transient existence is a testament to its singular focus: producing gametes. This division of labor ensures that each generation contributes uniquely to the life cycle, optimizing both survival and reproductive success.

In conclusion, the haploid gametophyte’s role in producing gametes is a cornerstone of the plant life cycle, blending simplicity with sophistication. Its specialized structures and functions exemplify nature’s ingenuity in ensuring sexual reproduction. Whether in the wild or under cultivation, appreciating and supporting the gametophyte’s role can enhance our stewardship of plant life, from preserving biodiversity to improving agricultural productivity. This tiny yet mighty phase reminds us that even the smallest players can have the most significant impact.

Are Spores Legal in Maryland? Understanding Current Laws and Regulations

You may want to see also

Diploid Sporophyte Function: Generates spores through meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity in offspring

In the life cycle of plants and certain algae, the diploid sporophyte plays a pivotal role in ensuring genetic diversity. This phase, characterized by its double set of chromosomes, is responsible for producing spores through meiosis. Meiosis, a type of cell division, reduces the chromosome number by half, creating haploid spores. These spores then develop into the gametophyte generation, which ultimately produces gametes for sexual reproduction. This process is fundamental to the alternation of generations, a life cycle pattern seen in many organisms, including ferns, mosses, and some algae.

Consider the fern as an illustrative example. The sporophyte, the visible fern plant we commonly recognize, generates spores on the undersides of its fronds. Each spore, being haploid, carries a single set of chromosomes. When conditions are favorable, these spores germinate into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes. These gametophytes produce both sperm and eggs, which, upon fertilization, restore the diploid state, giving rise to a new sporophyte. This cyclical process not only ensures the continuation of the species but also introduces genetic variation through the shuffling of genetic material during meiosis and fertilization.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this mechanism is crucial for horticulture and conservation efforts. For instance, in cultivating ferns, knowing that spores require specific humidity and light conditions to develop into gametophytes can significantly improve propagation success. Similarly, in preserving endangered plant species, conserving both sporophyte and gametophyte stages ensures genetic diversity, which is vital for the species’ resilience to environmental changes. This knowledge also aids in educational settings, where demonstrating the alternation of generations can deepen students’ appreciation for plant biology.

A comparative analysis highlights the efficiency of this system in promoting genetic diversity. Unlike organisms that rely solely on mitosis for reproduction, the inclusion of meiosis and fertilization in the life cycle allows for the recombination of genetic material. This recombination is essential for adaptation, as it produces offspring with unique traits that may better suit changing environments. For example, in a population of mosses, some individuals might develop greater drought tolerance due to genetic variation, ensuring the species’ survival in arid conditions.

In conclusion, the diploid sporophyte’s function of generating spores through meiosis is a cornerstone of genetic diversity in many organisms. This process not only sustains the life cycle but also fosters adaptability through the creation of genetically distinct offspring. Whether in the classroom, the garden, or conservation efforts, recognizing the significance of this mechanism enhances our ability to interact with and protect the natural world. By focusing on this specific function, we gain a deeper understanding of the intricate balance between continuity and variation in life.

Effective Strategies to Halt Recurrence in Spore: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A spore is haploid, meaning it contains a single set of chromosomes.

A sporophyte is diploid, meaning it contains two sets of chromosomes.

In the plant life cycle, a spore develops into a gametophyte, which produces gametes. The fusion of gametes forms a zygote, which then grows into a sporophyte. The sporophyte produces spores, completing the cycle.

No, spores and sporophytes belong to alternating generations in plants. Spores develop into the gametophyte generation, while sporophytes represent the sporophyte generation.