While both spores and sporangia are essential structures in the life cycles of certain organisms, particularly fungi and plants, they are not the same thing. A spore is a single-celled reproductive unit capable of developing into a new organism under favorable conditions. Spores are typically lightweight and durable, allowing them to disperse widely through air, water, or other means. In contrast, a sporangia (singular: sporangium) is the structure in which spores are produced and stored. It acts as a protective casing, often attached to the parent organism, and releases spores when mature. Thus, the sporangia is the spore-bearing organ, while the spores themselves are the individual reproductive units. Understanding this distinction is crucial for grasping the reproductive strategies of spore-producing organisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A spore is a single-celled reproductive unit capable of developing into a new organism without fertilization. A sporangia is a structure that produces and contains spores. |

| Function | Spores are the actual reproductive units that can grow into new organisms. Sporangia are the containers or organs where spores are produced and stored. |

| Location | Spores are found inside sporangia or released into the environment. Sporangia are located on specialized structures like ferns, fungi, or mosses. |

| Size | Spores are microscopic, typically ranging from 5 to 50 micrometers. Sporangia are larger, visible structures that house multiple spores. |

| Role in Life Cycle | Spores are part of the dispersal and survival stage in the life cycle. Sporangia are part of the reproductive stage, producing spores. |

| Mobility | Spores can be dispersed by wind, water, or animals. Sporangia are stationary structures attached to the parent organism. |

| Examples | Fern spores, fungal spores (e.g., mold). Fern sporangia, fungal sporangia (e.g., in Zygomycota). |

| Dependency | Spores are dependent on sporangia for their initial production and release. Sporangia are dependent on the parent organism for their development. |

| Structure | Spores are single-celled and often have protective walls. Sporangia are multicellular structures with walls that open to release spores. |

| Lifespan | Spores can remain dormant for long periods, sometimes years. Sporangia are temporary structures that degrade after releasing spores. |

What You'll Learn

- Spore Definition: A single-celled reproductive unit capable of growing into a new organism

- Sporangia Definition: A structure that produces and contains spores in plants and fungi

- Key Differences: Spores are cells; sporangia are spore-containing structures

- Function Comparison: Spores disperse; sporangia protect and release spores

- Examples in Nature: Ferns have sporangia on leaves; fungi release spores from sporangia

Spore Definition: A single-celled reproductive unit capable of growing into a new organism

Spores are single-celled reproductive units with an extraordinary ability to develop into new organisms under favorable conditions. This definition highlights their role as survival mechanisms in various life forms, particularly fungi, plants, and some bacteria. Unlike seeds, which contain embryonic plants and stored food, spores are minimalistic—often just a nucleus encased in a protective wall. This simplicity allows them to withstand harsh environments, such as extreme temperatures, drought, or chemical exposure, making them nature’s ultimate survivalists. For instance, fungal spores can remain dormant for years, only germinating when conditions are ideal for growth.

To understand spores, consider their function in reproduction. They are asexual units, meaning they do not require fertilization to develop into a new organism. This efficiency is crucial for species that thrive in unpredictable environments. For example, ferns release spores that disperse via wind, landing in diverse habitats where they can grow into new plants. Similarly, bacterial endospores, like those of *Clostridium botulinum*, can survive boiling water and only germinate when nutrients become available. This adaptability underscores the spore’s role as a resilient reproductive strategy.

While spores are the reproductive units themselves, sporangia are the structures that produce and contain them. This distinction is critical: a sporangium is a sac-like organ where spores are formed through cell division. For instance, in fungi like molds, sporangia release spores into the air, facilitating their dispersal. In plants like mosses, sporangia develop on the tips of stalks, releasing spores when mature. Confusing the two is common, but remembering that sporangia are the factories and spores are the products simplifies the relationship.

Practical applications of spore biology abound, particularly in agriculture and medicine. Farmers use fungal spores as bio-pesticides to control harmful insects without chemical toxins. For example, *Bacillus thuringiensis* spores are applied to crops to target caterpillars and beetles. In medicine, understanding spore resistance helps combat infections caused by spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridioides difficile*. Sterilization methods, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, are designed to destroy these resilient structures. This knowledge is essential for industries where contamination prevention is critical.

Finally, the study of spores offers insights into evolution and ecology. Their ability to disperse widely and survive extreme conditions has allowed species to colonize diverse habitats, from deserts to deep-sea hydrothermal vents. For enthusiasts, observing spore germination under a microscope can be a fascinating experiment. Simply place a fern spore on a damp paper towel, keep it in a sealed container, and watch as it develops into a tiny plant. This hands-on approach not only illustrates the spore’s potential but also deepens appreciation for its role in the natural world.

Do All Mushrooms Reproduce with Spores? Unveiling Fungal Reproduction Secrets

You may want to see also

Sporangia Definition: A structure that produces and contains spores in plants and fungi

Spores and sporangia are often confused, but they serve distinct roles in the life cycles of plants and fungi. While a spore is a reproductive cell capable of developing into a new organism, the sporangia is the specialized structure that produces and houses these spores. Think of it this way: if spores are the seeds, sporangia are the seed pods. This fundamental difference is crucial for understanding how these organisms propagate and survive in diverse environments.

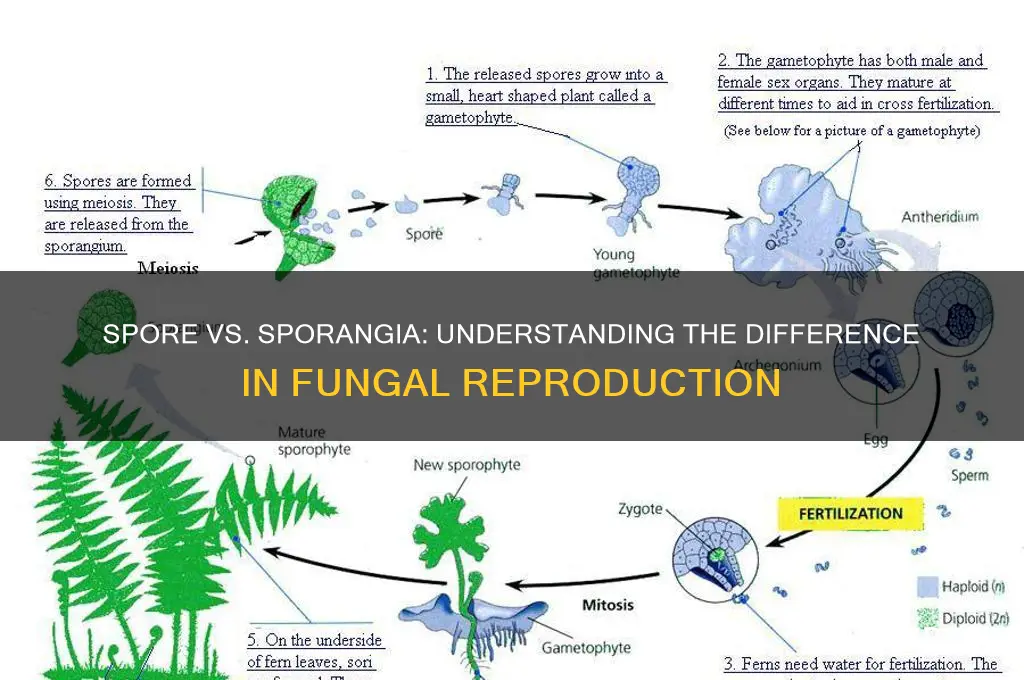

In plants, sporangia are commonly found in ferns and mosses, where they appear as small, often spherical or sac-like structures on the undersides of leaves or stems. For instance, in ferns, the sporangia cluster into structures called sori, which release spores when mature. These spores, once dispersed, can grow into new plants under favorable conditions. In fungi, sporangia are equally vital, particularly in species like bread mold (*Rhizopus*), where they form at the tips of stalks and release spores into the air. This process ensures widespread dispersal, increasing the chances of colonization in new habitats.

Understanding the function of sporangia is essential for practical applications, such as horticulture and mycology. For example, gardeners cultivating ferns must ensure proper humidity and light conditions to encourage sporangia development and spore release. Similarly, in fungal studies, researchers manipulate environmental factors like temperature and moisture to optimize sporangia formation, aiding in the study of fungal diseases or biotechnological applications. Knowing the difference between spores and sporangia allows for targeted interventions, whether in plant propagation or fungal control.

A comparative analysis highlights the efficiency of sporangia in ensuring survival. Unlike seeds, which require specific conditions to germinate, spores are highly resilient, capable of withstanding harsh environments such as drought or extreme temperatures. This adaptability is a direct result of the sporangia’s protective role, which shields spores until they are ready for dispersal. For instance, fungal sporangia often have thick walls that prevent desiccation, while plant sporangia may have mechanisms to release spores only when conditions are optimal.

In conclusion, while spores are the agents of reproduction, sporangia are the architects of their production and dispersal. This relationship underscores the sophistication of plant and fungal life cycles. By focusing on the sporangia’s role, we gain insights into the mechanisms that drive biodiversity and survival strategies in these organisms. Whether for scientific research, agriculture, or conservation, distinguishing between spores and sporangia is key to harnessing their potential effectively.

Exploring Fungal Diversity: Do Tropical Islands Harbor More Spores?

You may want to see also

Key Differences: Spores are cells; sporangia are spore-containing structures

Spores and sporangia, though often mentioned together, serve distinct roles in the life cycles of plants and fungi. A spore is a single, specialized cell capable of developing into a new organism under favorable conditions. Think of it as a microscopic survival pod, equipped with a protective coat to withstand harsh environments. In contrast, a sporangium is a multicellular structure that houses and produces spores. Imagine a sporangium as a factory, where spores are manufactured and stored until they are ready to be released.

To illustrate, consider the fern life cycle. On the underside of fern leaves, you’ll find clusters of sporangia, each containing hundreds of spores. When mature, these sporangia release their spores into the wind. Each spore, if it lands in a suitable environment, can grow into a tiny, heart-shaped gametophyte, which eventually develops into a new fern. Here, the spore is the reproductive unit, while the sporangium is the protective and productive housing.

Understanding this distinction is crucial for practical applications, such as gardening or laboratory work. For instance, if you’re cultivating mosses or ferns, knowing that sporangia are the spore-bearing structures helps you identify the right time to collect spores for propagation. Similarly, in microbiology, recognizing that spores are individual cells aids in sterilization processes, as spores often require specific conditions (e.g., high heat or pressure) to be inactivated.

From an evolutionary perspective, the separation of spores and sporangia highlights a division of labor. Spores focus on dispersal and survival, while sporangia ensure efficient production and protection. This specialization allows organisms to thrive in diverse environments, from arid deserts to humid forests. For example, fungal sporangia often have mechanisms to eject spores forcefully, maximizing their reach, while the spores themselves can remain dormant for years, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate.

In summary, while spores and sporangia are interconnected, their functions are fundamentally different. Spores are the reproductive cells, designed for dispersal and growth, whereas sporangia are the structures that produce, store, and release these cells. Recognizing this distinction not only clarifies biological concepts but also enhances practical skills in fields like horticulture, microbiology, and ecology.

How Moss Reproduces: Understanding the Role of Spores in Growth

You may want to see also

Function Comparison: Spores disperse; sporangia protect and release spores

Spores and sporangia, though often mentioned together, serve distinct roles in the life cycles of plants and fungi. Spores are the reproductive units designed for dispersal, capable of traveling through air, water, or soil to colonize new environments. In contrast, sporangia are the protective structures that house and nurture these spores until conditions are optimal for release. Understanding this functional difference is key to grasping their unique contributions to survival and propagation.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern, a classic example of spore-sporangia interaction. On the underside of fern fronds, you’ll find clusters of sporangia, often referred to as sori. Inside each sporangium, spores develop through meiosis, a process that ensures genetic diversity. Once mature, the sporangium dries and splits open, releasing spores into the wind. This release mechanism is not random; it’s triggered by environmental cues like humidity and temperature, ensuring spores disperse when conditions favor germination. For gardeners cultivating ferns, maintaining moderate humidity and avoiding overwatering can mimic these natural triggers, promoting healthy spore release.

The protective role of sporangia is particularly critical in harsh environments. In fungi like *Phycomyces*, sporangia are encased in thick walls that shield spores from desiccation, UV radiation, and predators. This protective barrier ensures that spores remain viable until they reach a suitable habitat. For instance, in arid regions, sporangia may remain dormant for years, only releasing spores after rare rainfall events. This adaptive strategy highlights the sporangium’s role as a survival capsule, contrasting sharply with the spore’s mission to explore and colonize.

From a practical standpoint, distinguishing between spores and sporangia is essential in fields like agriculture and medicine. Farmers combating fungal pathogens, such as *Phytophthora*, must target sporangia to prevent spore dispersal, which can devastate crops. Fungicides are often applied during periods of high humidity, when sporangia are most likely to release spores. Similarly, in mycology labs, researchers isolate sporangia to study spore development, a process requiring sterile techniques to avoid contamination. This targeted approach underscores the importance of understanding their functional differences.

In summary, while spores are the pioneers of colonization, sporangia are the guardians of their journey. Their symbiotic relationship ensures the continuity of species across diverse ecosystems. Whether you’re a gardener, farmer, or scientist, recognizing their distinct functions allows for more effective strategies in cultivation, pest control, and research. By appreciating this division of labor, we gain deeper insight into the intricate mechanisms driving life’s persistence.

Troubleshooting 'Could Not Start the Renderer' Error in Spore: A Guide

You may want to see also

Examples in Nature: Ferns have sporangia on leaves; fungi release spores from sporangia

Ferns provide a vivid example of how sporangia function in nature. On the underside of their fronds, often in clusters called sori, these plants develop sporangia—tiny, sac-like structures that produce and contain spores. Each sporangium is a microcosm of reproductive efficiency, releasing hundreds of spores when mature. Unlike seeds, spores are single-celled and lightweight, allowing them to disperse easily on wind currents. This adaptation ensures ferns can colonize new areas, even in challenging environments like dense forests or rocky crevices.

Fungi, on the other hand, showcase a different utilization of sporangia. In species like bread mold (*Rhizopus*), sporangia are swollen structures at the tips of stalks, filled with spores. When mature, the sporangium wall ruptures, releasing spores into the environment. This mechanism is crucial for fungal reproduction, enabling rapid spread across substrates like decaying organic matter. Unlike ferns, fungi often produce spores in vast quantities, compensating for the low probability of individual spore survival. This strategy highlights the sporangium’s role as a spore factory, optimized for mass dispersal.

Comparing ferns and fungi reveals distinct evolutionary strategies tied to their sporangia. Ferns rely on external conditions—like moisture for spore germination—and thus invest in protective structures like the indusium, a thin membrane covering the sori. Fungi, however, thrive in diverse habitats, from soil to living hosts, and their sporangia are adapted for quick release and dispersal. Both organisms illustrate how sporangia serve as specialized organs for spore production, yet their design and function diverge based on ecological needs.

For enthusiasts or educators, observing these processes firsthand can deepen understanding. To study fern sporangia, collect mature fronds and examine the underside with a magnifying glass or microscope. For fungi, cultivate mold on bread in a sealed container, noting the development of sporangia over days. These activities not only clarify the distinction between spores and sporangia but also demonstrate their symbiotic relationship in reproductive biology. By focusing on these examples, one can appreciate the precision with which nature employs sporangia to ensure species survival.

Surviving Spores: Understanding Their Longevity at Room Temperature

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, a spore is a single reproductive cell produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, while a sporangia is the structure or organ in which spores are produced and stored.

The main function of a spore is to serve as a means of asexual reproduction and dispersal, allowing organisms to survive harsh conditions and colonize new environments.

Sporangia are typically found in ferns, mosses, fungi, and other spore-producing organisms, often located on specialized structures like the undersides of fern leaves or fungal hyphae.

Yes, some organisms, like certain fungi, produce different types of spores (e.g., sexual and asexual spores) within the same sporangia or in separate structures.

Spores are haploid, single-celled structures produced by asexual or sexual reproduction, while seeds are diploid, multicellular structures that contain an embryo and stored food, typically produced by flowering plants.