The question of whether a vegetative cell is harder to stain than a spore is a significant one in microbiology, as it directly impacts the accuracy and efficiency of bacterial identification and analysis. Vegetative cells, which are the actively growing and metabolizing form of bacteria, typically have a less complex cell wall structure compared to spores, which are dormant, highly resistant forms. This difference in cell wall composition and structure can affect the permeability and binding of stains, potentially making vegetative cells more susceptible to certain staining techniques. However, spores present a unique challenge due to their thick, impermeable outer layers, which may require specialized staining methods, such as the Schaeffer-Fulton or Dorner methods, to effectively penetrate and visualize the spore structure. Understanding these differences is crucial for microbiologists, as it enables them to select the most appropriate staining technique for a given sample, ensuring accurate results and informed decision-making in various applications, from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Cell Wall Composition | Vegetative cells have a thinner, less complex cell wall primarily composed of peptidoglycan. Spores have a thicker, multi-layered cell wall with additional protective layers like spore coat, cortex, and sometimes exosporium, making them more resistant to staining. |

| Permeability | Vegetative cells are more permeable due to their thinner cell wall, allowing stains to penetrate more easily. Spores are less permeable due to their thick, protective layers, making them harder to stain. |

| Heat Resistance | Vegetative cells are less heat-resistant and can be easily damaged by heat fixation, which may affect staining. Spores are highly heat-resistant and require more intense heat fixation, which can further reduce their permeability to stains. |

| Staining Techniques | Vegetative cells can be stained using simple techniques like Gram staining. Spores often require specialized techniques like the Schaeffer-Fulton or Dorner methods, which involve heat or chemical treatment to increase permeability. |

| Stain Retention | Vegetative cells retain stains well due to their higher permeability. Spores may retain stains poorly due to their low permeability, often appearing as unstained or lightly stained structures. |

| Endospore Presence | Vegetative cells do not have endospores. Spores are endospores themselves, which are highly resistant to staining due to their unique structure. |

| Metabolic Activity | Vegetative cells are metabolically active, which can influence staining results. Spores are metabolically dormant, making them less reactive to stains. |

| Size and Shape | Vegetative cells are generally larger and more varied in shape. Spores are smaller, more uniform, and often oval or spherical, which can affect staining uniformity. |

| Chemical Resistance | Vegetative cells are less resistant to chemicals used in staining. Spores are highly resistant to chemicals, requiring stronger reagents for effective staining. |

| Staining Time | Vegetative cells stain relatively quickly. Spores require longer staining times due to their resistance. |

What You'll Learn

Cell Wall Permeability Differences

The permeability of cell walls plays a pivotal role in determining how easily a cell can be stained, and this characteristic varies significantly between vegetative cells and spores. Vegetative cells, the actively growing and metabolizing form of bacteria, possess a cell wall that is more permeable compared to the highly resistant cell wall of a spore. This difference in permeability is primarily due to the composition and structure of the cell walls. Vegetative cell walls are typically composed of peptidoglycan, which allows for the passage of smaller molecules, including many stains. In contrast, spore cell walls are enriched with additional layers, such as a thick layer of spore-specific peptidoglycan and an outer coat of keratin-like proteins, making them far less permeable.

To illustrate, consider the staining process using a common dye like crystal violet in the Gram staining procedure. Vegetative cells readily take up the stain due to their more permeable cell walls, appearing purple under a microscope. Spores, however, often require more aggressive methods, such as heat fixation or prolonged exposure to the stain, to penetrate their robust cell wall. For instance, in the endospore staining process, a malachite green dye is applied at an elevated temperature (around 80°C) to force the dye through the spore’s impermeable layers. This example highlights how cell wall permeability directly influences staining efficiency.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these permeability differences is crucial for microbiologists and lab technicians. When working with mixed cultures containing both vegetative cells and spores, it’s essential to tailor staining techniques to account for these variations. For vegetative cells, standard staining protocols are often sufficient, but spores may require specialized techniques like the Schaeffer-Fulton method, which combines heat and prolonged staining to ensure accurate results. Ignoring these differences can lead to misinterpretation of microbial populations, particularly in environmental or clinical samples where both forms may coexist.

A comparative analysis reveals that the impermeability of spore cell walls is an evolutionary adaptation for survival in harsh conditions. While this impermeability protects spores from environmental stressors, it also presents a challenge in laboratory settings. Vegetative cells, being more permeable, are easier to stain and study, but their susceptibility to environmental damage underscores the trade-off between accessibility and resilience. This comparison emphasizes the importance of selecting appropriate staining methods based on the cell type being examined.

In conclusion, cell wall permeability differences between vegetative cells and spores are a critical factor in staining efficacy. By recognizing these differences and employing tailored techniques, researchers can ensure accurate and reliable results in microbial identification and analysis. Whether in a clinical lab or a research setting, this knowledge is indispensable for overcoming the unique challenges posed by each cell type.

Discovering Your Next Nest Spore: A Beginner's Guide to Finding It

You may want to see also

Spore Coat Stain Resistance

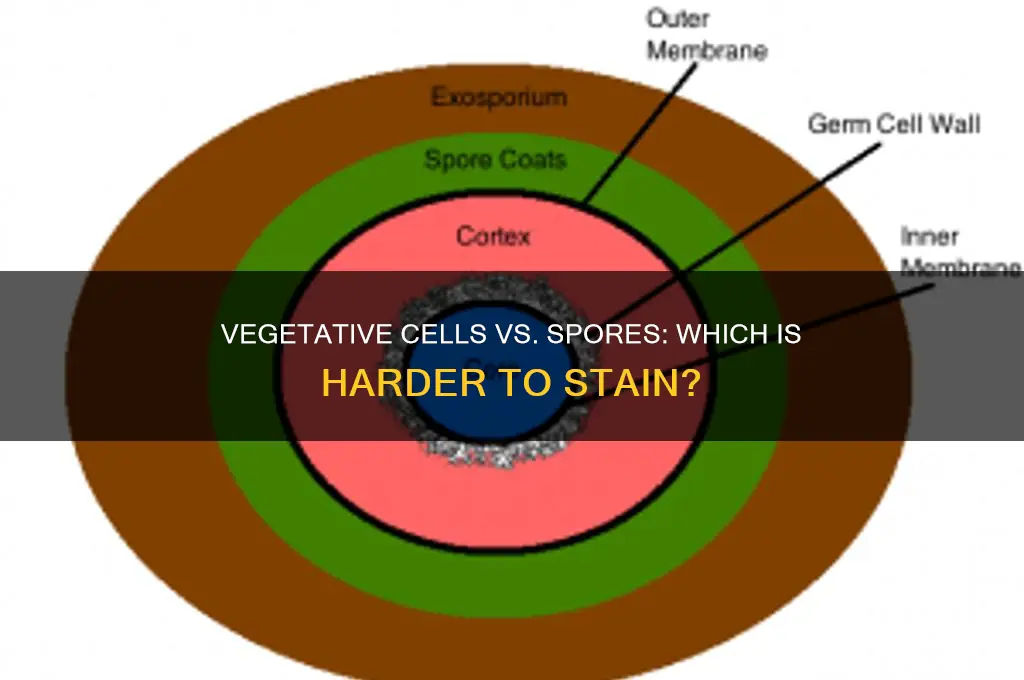

The spore coat, a multi-layered protective barrier surrounding bacterial spores, presents a unique challenge in staining techniques due to its inherent stain resistance. This resistance is a critical survival mechanism for spores, allowing them to withstand harsh environmental conditions, including desiccation, heat, and chemicals. However, for microbiologists, this resistance complicates the process of visualizing spores under a microscope, as traditional staining methods often fail to penetrate the spore coat effectively.

To overcome this challenge, specialized staining techniques have been developed, such as the Schaeffer-Fulton method, which employs a combination of heat and malachite green dye to force the stain through the spore coat. The process involves heating a smear of bacterial cells, including spores, to 80-100°C for 5-10 minutes, followed by the application of malachite green dye for 2-3 minutes. This heat treatment helps to weaken the spore coat, allowing the dye to penetrate and stain the spores a characteristic green color. After staining, the smear is counterstained with safranin to differentiate between spores and vegetative cells, which appear red.

In contrast to vegetative cells, which have a more permeable cell wall and membrane, spores require a more aggressive approach to staining due to their unique physiology. The spore coat's resistance to staining is not only a physical barrier but also a chemical one, as it contains dipicolinic acid, a compound that can interfere with dye binding. This highlights the importance of understanding the spore's structure and composition when selecting a staining technique. For instance, using a simple Gram stain may not be sufficient for spore visualization, as the spore coat can prevent the crystal violet dye from penetrating, resulting in false-negative results.

When working with spores, it is essential to consider the age and species of the bacteria, as these factors can influence the spore coat's stain resistance. Younger spores, for example, may have a more permeable coat, making them easier to stain than older, more mature spores. Additionally, certain bacterial species, such as Bacillus anthracis, have a particularly thick and resistant spore coat, requiring more specialized staining techniques. In these cases, a modified staining protocol, such as the Dorner method, which uses heat and a mixture of dyes, may be necessary to achieve adequate staining.

In practical terms, achieving successful spore staining requires attention to detail and adherence to specific protocols. Key considerations include maintaining a consistent heating temperature, using high-quality dyes, and ensuring proper smear preparation. For optimal results, it is recommended to use a heating block or water bath to control the temperature during the staining process. Furthermore, storing dyes in a cool, dark place can help preserve their potency and effectiveness. By understanding the unique challenges posed by spore coat stain resistance and employing specialized techniques, microbiologists can accurately visualize and identify spores, facilitating more effective diagnosis and research.

Understanding the Fascinating Process of Moss Spore Production and Dispersal

You may want to see also

Metabolism and Stain Uptake

Vegetative cells and spores exhibit distinct metabolic activities, which directly influence their susceptibility to staining. Vegetative cells, being metabolically active, maintain permeable cell membranes to facilitate nutrient uptake and waste removal. This permeability allows stains to penetrate more easily, often resulting in rapid and uniform staining. For instance, when using a basic dye like methylene blue, vegetative cells typically stain within 2–5 minutes due to their active transport systems and fluid membrane structure. In contrast, spores, with their dormant metabolic state, possess a highly impermeable cell wall and membrane, often reinforced with layers like the exosporium and spore coat. This impermeability significantly hinders stain penetration, requiring prolonged exposure or specialized techniques, such as heat fixation or chemical pretreatment, to achieve effective staining.

To optimize stain uptake in vegetative cells, consider the metabolic state and environmental conditions. For example, cells in logarithmic growth phase, where metabolic activity is highest, stain more readily than those in stationary phase. Maintaining optimal pH (typically 6.5–7.5) and temperature (37°C for most bacteria) ensures peak metabolic function, enhancing stain absorption. Conversely, staining spores demands strategies to bypass their protective barriers. A common method is the Schaeffer-Fulton technique, which involves heating spores in water to 80°C for 10 minutes, followed by rapid cooling and staining with malachite green. This process compromises the spore’s impermeability, allowing the stain to penetrate and bind to the spore’s inner structures.

The metabolic differences between vegetative cells and spores also affect the choice of stains and staining protocols. Vegetative cells respond well to simple stains like Gram stain, which relies on cell wall composition and membrane integrity. However, spores often require more robust stains, such as spore-specific dyes like nigrosin or India ink, which highlight spores by negative staining, leaving them unstained against a dark background. Understanding these metabolic nuances enables precise control over staining outcomes, ensuring accurate identification and differentiation in microbiological analyses.

A practical tip for researchers is to assess the metabolic activity of the sample prior to staining. For vegetative cells, a quick viability test using a dye like resazurin can confirm active metabolism, ensuring optimal staining conditions. For spores, pretreatment with lysozyme or enzymes like pronase can degrade the spore coat, enhancing stain uptake without resorting to heat shock. By tailoring the approach to the metabolic state of the cell or spore, microbiologists can achieve consistent and reliable staining results, critical for diagnostic and research applications.

In summary, the metabolic activity of vegetative cells and spores plays a pivotal role in stain uptake, dictating the choice of staining techniques and protocols. While vegetative cells stain readily due to their active metabolism and permeable membranes, spores require targeted methods to overcome their impermeable barriers. By leveraging this knowledge, microbiologists can optimize staining procedures, ensuring accurate and efficient differentiation between these two bacterial forms.

Can Steaming Effectively Eliminate Ringworm Spores? Expert Insights Revealed

You may want to see also

Dormancy vs. Active Staining

Vegetative cells and spores present distinct challenges in staining due to their contrasting physiological states. Dormant spores, characterized by their metabolically inactive state, often exhibit a robust outer coat that resists common staining techniques. This resistance necessitates specialized methods, such as heat or chemical pretreatments, to penetrate the spore’s protective layers. In contrast, vegetative cells, being metabolically active, generally lack this protective barrier, making them more receptive to standard staining procedures. However, their active state can also lead to rapid degradation or altered permeability, complicating the staining process in certain scenarios.

To effectively stain dormant spores, a process known as spore staining is employed, which typically involves heat fixation or treatment with chemicals like ethanol or acetone. For example, the Schaeffer-Fulton method uses heat to dehydrate the spore coat, allowing dyes like malachite green to penetrate. This method is particularly useful for differentiating spores from vegetative cells in a mixed sample. The key takeaway here is that dormancy in spores requires a more aggressive approach to achieve successful staining, whereas vegetative cells often respond well to milder techniques like simple fixation and staining with basic dyes such as Gram stain.

When working with active vegetative cells, the challenge shifts from penetration to preservation. These cells are more susceptible to damage from harsh chemicals or prolonged exposure to staining reagents. For instance, over-fixation can lead to cell wall hardening, reducing dye uptake, while under-fixation may result in cell lysis. Practical tips include using gentle fixatives like 10% formalin for 10–15 minutes and avoiding excessive heat. Additionally, staining should be performed promptly to minimize metabolic changes that could affect dye binding. This highlights the importance of balancing preservation and permeability when staining active cells.

A comparative analysis reveals that the staining difficulty between vegetative cells and spores is largely determined by their physiological state. Dormant spores require methods that overcome their protective mechanisms, making staining more labor-intensive but often more consistent once the barrier is breached. Active vegetative cells, while easier to stain initially, demand careful handling to maintain their integrity during the process. For researchers and lab technicians, understanding these differences is crucial for selecting the appropriate staining protocol and interpreting results accurately.

In conclusion, the dormancy of spores and the active state of vegetative cells dictate distinct staining strategies. While spores necessitate pretreatments to access their interior, vegetative cells require gentle handling to preserve their structure. By tailoring the approach to the cell’s physiological state, one can achieve reliable and reproducible staining results, ensuring clarity in microbiological analyses. This nuanced understanding bridges the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application in staining techniques.

Are C. Diff Spores Airborne? Unraveling the Transmission Mystery

You may want to see also

Staining Techniques Comparison

Vegetative cells and spores present distinct challenges in staining due to their structural and physiological differences. Vegetative cells, being metabolically active, have more permeable cell walls and membranes, which can facilitate the uptake of stains but also make them more susceptible to damage during the staining process. Spores, on the other hand, are dormant, highly resistant structures with thick, impermeable coats that often require pretreatment to allow stains to penetrate. This fundamental difference necessitates tailored staining techniques to achieve accurate and reliable results.

Analytical Comparison of Staining Techniques

For vegetative cells, simple staining methods like Gram staining are often sufficient. The Gram stain, which involves crystal violet, iodine, alcohol, and safranin, effectively differentiates Gram-positive and Gram-negative cells based on cell wall composition. The permeable nature of vegetative cells allows for rapid dye penetration, making this technique efficient. However, spores’ impermeable exosporium and cortex layers require more aggressive methods. One common approach is the Schaeffer-Fulton stain, which uses heat to rupture the spore coat, allowing malachite green to penetrate. This technique highlights spores in contrast to vegetative cells, stained with safranin, but requires careful temperature control to avoid damaging the sample.

Instructive Guide to Pretreatment Steps

To enhance spore staining, pretreatment is essential. Heat fixation, as in the Schaeffer-Fulton method, is a standard practice, but alternatives like chemical pretreatment with hydrochloric acid or enzymatic digestion can also improve dye penetration. For vegetative cells, fixation with methanol or heat is typically milder, preserving cell integrity while preparing the sample for staining. When working with mixed cultures, such as *Bacillus* species, which produce both vegetative cells and spores, combining these techniques ensures both forms are adequately stained. For example, a 5-minute heat treatment at 80°C followed by a 15-minute immersion in malachite green effectively stains spores, while a subsequent safranin counterstain highlights vegetative cells.

Persuasive Argument for Technique Selection

Choosing the right staining technique depends on the research question and sample composition. For clinical microbiology, where rapid identification of pathogens is critical, the Gram stain’s speed and simplicity make it indispensable for vegetative cells. However, in environmental or food microbiology, where spore detection is paramount, the Schaeffer-Fulton stain’s specificity for spores is invaluable. Researchers must weigh the trade-offs: simpler techniques may sacrifice detail, while more complex methods require additional time and resources. For instance, while the Gram stain takes 3–5 minutes, the Schaeffer-Fulton method requires 30–45 minutes, including pretreatment and staining steps.

Descriptive Example and Practical Tips

Consider a scenario where a soil sample contains *Bacillus subtilis*, a bacterium known to form spores. A standard Gram stain might reveal vegetative cells but fail to highlight spores, leading to an incomplete analysis. By employing the Schaeffer-Fulton stain, the spores appear green against a pink background of vegetative cells, providing a comprehensive view of the sample. Practical tips include using a water bath for consistent heat application during spore staining and ensuring all reagents are fresh to avoid false results. For mixed samples, always counterstain to differentiate cell types, and use a 100x oil immersion objective for clear visualization of spore morphology.

Comparative Takeaway

While vegetative cells are generally easier to stain due to their permeability, spores require specialized techniques to overcome their resistance. The choice of staining method should align with the sample’s characteristics and the study’s objectives. By understanding the structural differences between these cell types and applying appropriate techniques, researchers can achieve accurate, reproducible results, whether in a clinical lab or field study. Mastery of these techniques not only enhances diagnostic accuracy but also deepens our understanding of microbial diversity and behavior.

Understanding Spore Mods: How They Work on Steam Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, vegetative cells are generally easier to stain than spores due to their less complex cell wall structure, which allows stains to penetrate more readily.

Spores have a thick, impermeable cell wall composed of materials like sporopollenin, which resists most stains, requiring specialized techniques like heat fixation or chemical treatment to enhance staining.

While some staining methods work for both, spores often require additional steps, such as heat or chemical pretreatment, to break down their resistant cell wall, whereas vegetative cells can typically be stained directly.