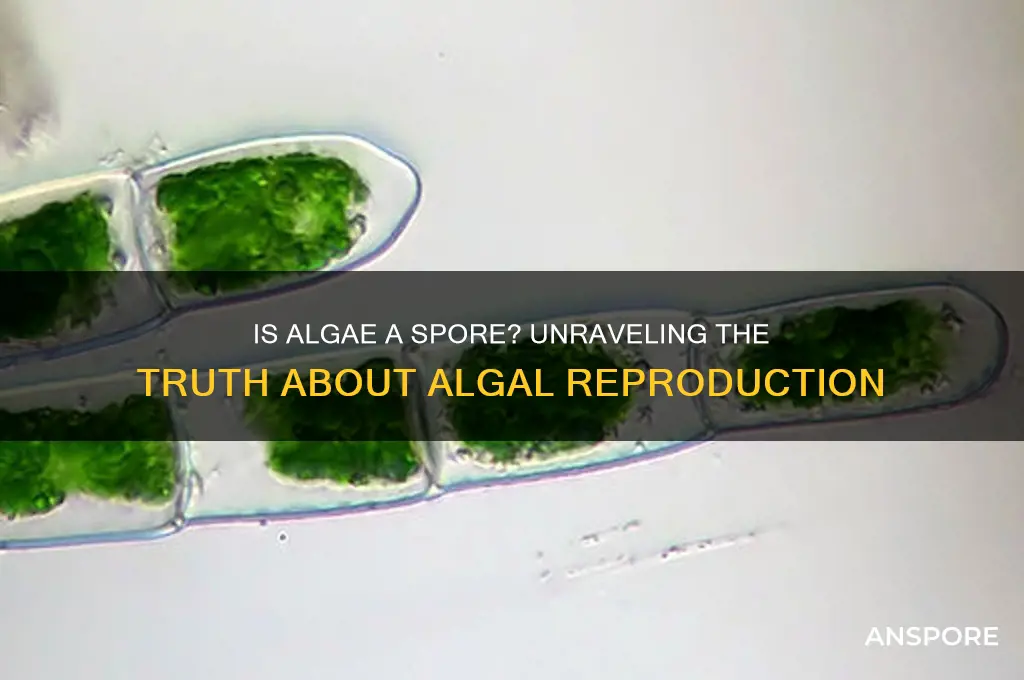

Algae, a diverse group of photosynthetic organisms, often raise questions about their reproductive methods, particularly whether they produce spores. While some algae, such as certain species of green algae (Chlorophyta) and red algae (Rhodophyta), do indeed release spores as part of their life cycle, not all algae follow this pattern. For instance, diatoms reproduce primarily through cell division, and many brown algae (Phaeophyta) rely on gametes for reproduction. The presence of spores in algae is therefore species-dependent, reflecting the wide variability in their life cycles and reproductive strategies. Understanding whether a specific type of algae produces spores requires examining its taxonomic classification and life cycle stages.

What You'll Learn

- Algae Reproduction Methods: Algae reproduce sexually, asexually, or via spores, depending on species and environmental conditions

- Spore Formation in Algae: Some algae produce spores as part of their life cycle for dispersal and survival

- Types of Algal Spores: Algae produce zoospores, aplanospores, and akinetes, each with unique functions

- Role of Spores in Algae: Spores aid in algae's resilience, dispersal, and adaptation to harsh environments

- Algae vs. Plants Spores: Algae spores differ from plant spores in structure, function, and life cycle stages

Algae Reproduction Methods: Algae reproduce sexually, asexually, or via spores, depending on species and environmental conditions

Algae, a diverse group of photosynthetic organisms, employ a range of reproductive strategies that ensure their survival across various environments. One of the most intriguing aspects of algae reproduction is their ability to switch between sexual, asexual, and spore-based methods depending on species and environmental cues. This adaptability allows them to thrive in conditions ranging from nutrient-rich waters to arid soils. For instance, some green algae like *Chlamydomonas* can reproduce sexually when nutrients are scarce, ensuring genetic diversity, while others, such as *Spirogyra*, fragment into smaller pieces asexually to rapidly colonize new areas.

To understand spore-based reproduction in algae, consider the life cycle of *Ulva* (sea lettuce), a common green alga. Under favorable conditions, *Ulva* reproduces asexually by releasing spores called zoospores, which swim using flagella to find suitable habitats. When environmental stress occurs, such as temperature changes or desiccation, *Ulva* may produce thicker-walled spores called aplanospores, which can survive harsh conditions until they germinate. This dual strategy highlights how spores act as a survival mechanism, bridging the gap between asexual and sexual reproduction in algae.

For those cultivating algae, understanding these reproductive methods is crucial. In aquaculture, controlling light, temperature, and nutrient levels can manipulate algae to reproduce asexually for biomass production. For example, maintaining a temperature of 25–30°C and a pH of 7–8.5 in *Chlorella* cultures promotes rapid asexual division. Conversely, inducing sexual reproduction in species like *Dunaliella* requires nutrient deprivation, which triggers the formation of gametes. Practical tip: monitor nitrate and phosphate levels; reducing them below 0.5 ppm can initiate sexual phases in some species.

Comparatively, spore-based reproduction in algae shares similarities with fungal and fern life cycles but differs in key ways. While fungal spores are primarily for dispersal, algal spores often serve as both dispersal agents and dormant survival structures. For instance, *Zygnema*, a filamentous green alga, produces akinetes—thick-walled spores resistant to freezing and drying. This contrasts with asexual fragmentation, which lacks such resilience. Takeaway: spores are not just a reproductive tool but a survival strategy, making algae uniquely resilient in fluctuating environments.

Finally, the choice of reproductive method in algae is deeply tied to their ecological role. In aquatic ecosystems, asexual reproduction via spores or fragmentation allows algae to dominate nutrient-rich zones rapidly, contributing to blooms. However, sexual reproduction ensures genetic diversity, critical for adapting to long-term environmental changes. For researchers and hobbyists, observing these transitions—such as the formation of zygotes in *Volvox* under a microscope—offers insights into algal ecology. Practical tip: use a 40x objective lens to observe spore germination, a process that typically occurs within 24–48 hours under optimal conditions.

Using Grub Control with Milky Spore: Compatibility and Best Practices

You may want to see also

Spore Formation in Algae: Some algae produce spores as part of their life cycle for dispersal and survival

Algae, often overlooked in discussions of spore-producing organisms, play a fascinating role in the natural world through their unique reproductive strategies. Among these strategies, spore formation stands out as a critical mechanism for dispersal and survival. Unlike plants that rely on seeds, certain algae species produce spores as part of their life cycle, ensuring their persistence in diverse and often harsh environments. These spores are lightweight, resilient, and capable of traveling long distances via wind, water, or other vectors, allowing algae to colonize new habitats efficiently.

Consider the life cycle of *Chara*, a genus of green algae commonly found in freshwater environments. During its reproductive phase, *Chara* develops specialized structures called sporangia, which release spores known as zoospores. These zoospores are motile, equipped with flagella that enable them to swim through water until they find a suitable substrate to settle and grow. This process not only ensures the survival of the species but also facilitates its spread across different aquatic ecosystems. Such adaptability highlights the evolutionary advantage of spore formation in algae.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore formation in algae has implications for both ecological conservation and biotechnology. For instance, algae spores can be harnessed in aquaculture to enhance water quality and provide food for aquatic organisms. In biotechnology, spores from algae like *Dunaliella* are studied for their high beta-carotene content, which has applications in nutraceuticals and biofuel production. To cultivate algae spores effectively, maintain a controlled environment with optimal light (10,000–20,000 lux), temperature (20–25°C), and nutrient levels (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus in balanced ratios). Regular monitoring of pH (6.5–8.5) and salinity is also crucial for successful spore germination and growth.

Comparatively, spore formation in algae differs significantly from that in fungi or ferns, primarily due to the aquatic nature of algae and their simpler cellular structures. While fungal spores are often airborne and ferns produce spores in large quantities, algae spores are typically waterborne and produced in smaller, more targeted quantities. This distinction underscores the specialized role of spores in algae’s survival strategies, particularly in dynamic aquatic environments. For example, red algae like *Porphyra* release spores that can remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate, a trait less common in terrestrial spore-producing organisms.

In conclusion, spore formation in algae is a remarkable adaptation that ensures their dispersal and survival in diverse ecosystems. By studying this process, we gain insights into the resilience of algal species and their potential applications in various fields. Whether in ecological restoration, biotechnology, or aquaculture, understanding and harnessing algal spores can lead to innovative solutions for both environmental and industrial challenges. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, exploring the intricacies of algal spore formation opens a window into the extraordinary world of these microscopic organisms.

Are Psilocybe Mushroom Spores Legal to Own? Exploring the Law

You may want to see also

Types of Algal Spores: Algae produce zoospores, aplanospores, and akinetes, each with unique functions

Algae, often misunderstood as simple organisms, exhibit remarkable complexity in their reproductive strategies. Among their diverse spore types, zoospores stand out for their motility. These microscopic, flagellated cells propel themselves through water, seeking optimal conditions for growth. This mobility is a survival advantage, allowing algae to colonize new habitats swiftly. For instance, in aquaculture, zoospores of *Ulva* (sea lettuce) can rapidly spread, sometimes leading to green tides if left unchecked. Understanding zoospore behavior is crucial for both ecological management and biotechnological applications, such as algae cultivation for biofuels.

In contrast to the active zoospores, aplanospores are non-motile spores produced by algae under unfavorable conditions. These spores serve as a dormant survival mechanism, akin to seeds in plants. Aplanospores are often thicker-walled, providing resistance to harsh environments like desiccation or extreme temperatures. For example, *Chlamydomonas*, a common green alga, forms aplanospores when water availability decreases. This adaptability highlights the resilience of algae and their ability to thrive in fluctuating ecosystems. Researchers studying algal blooms often focus on aplanospore formation to predict and mitigate outbreaks.

Akinetes represent another specialized spore type, primarily found in cyanobacteria and certain algae like *Anabaena*. These spores are larger and metabolically inactive, designed for long-term survival in adverse conditions. Akinetes can remain dormant for years, only germinating when environmental cues signal favorable conditions. This trait is particularly useful in nutrient-poor environments, where sudden resource availability triggers akinete activation. For instance, in agricultural settings, akinetes of *Nostoc* can enhance soil fertility by fixing nitrogen upon germination. Harnessing akinete biology could revolutionize sustainable farming practices.

Each spore type—zoospores, aplanospores, and akinetes—serves a distinct ecological role, reflecting algae’s adaptability to diverse environments. Zoospores facilitate rapid colonization, aplanospores ensure short-term survival, and akinetes provide long-term persistence. This diversity underscores algae’s importance in ecosystems and their potential in biotechnology. For hobbyists cultivating algae at home, recognizing these spores can optimize growth conditions. For example, maintaining water circulation encourages zoospore dispersal, while controlled drying can induce aplanospore formation. Practical knowledge of these spores transforms algae from a scientific curiosity into a manageable resource.

In summary, the study of algal spores reveals a sophisticated reproductive toolkit tailored to environmental challenges. Whether through zoospore motility, aplanospore resilience, or akinete dormancy, algae demonstrate evolutionary ingenuity. This knowledge not only deepens our understanding of microbial life but also offers practical applications in industries from aquaculture to agriculture. By focusing on these spore types, we unlock the full potential of algae as both ecological indicators and biotechnological assets.

Exploring Pteridophytes: Understanding Their Spore-Based Reproduction and Classification

You may want to see also

Role of Spores in Algae: Spores aid in algae's resilience, dispersal, and adaptation to harsh environments

Algae, often perceived as simple organisms, exhibit remarkable complexity in their reproductive strategies. One of their most fascinating adaptations is the production of spores, which serve as a cornerstone for survival in diverse and often hostile environments. These microscopic structures are not merely reproductive units but are key to the algae’s resilience, dispersal, and ability to thrive in conditions that would be lethal to many other life forms.

Consider the harsh realities of environments where algae flourish: arid deserts, freezing polar regions, and even the depths of the ocean. Spores act as algae’s survival capsules, enabling them to endure extreme temperatures, desiccation, and nutrient scarcity. For instance, certain species of cyanobacteria form akinetes—thick-walled spores that can remain dormant for years, reactivating when conditions improve. This dormancy is a strategic pause, ensuring that the algae’s genetic lineage persists even when active growth is impossible. Practical applications of this resilience are seen in biotechnology, where algae spores are studied for their potential in developing drought-resistant crops.

Dispersal is another critical role of spores, allowing algae to colonize new habitats far from their origin. Wind, water, and even animals carry these lightweight, durable structures across vast distances. Take *Chlamydomonas*, a green alga that produces zoospores equipped with flagella, enabling them to swim to favorable environments. Similarly, fungal-like algae such as *Vaulotaxus* release spores that can travel through air currents, settling in nutrient-rich areas. This dispersal mechanism is not just a passive process but a calculated strategy to maximize the species’ geographic reach. For hobbyists cultivating algae in aquariums, understanding spore dispersal can help in maintaining diverse and healthy ecosystems by ensuring proper water circulation and filtration.

Adaptation is where spores truly shine, showcasing algae’s evolutionary ingenuity. Spores can undergo genetic recombination, producing offspring with traits better suited to their environment. This is particularly evident in red algae, which alternate between diploid and haploid life stages, with spores playing a pivotal role in this cycle. Such adaptability is crucial in rapidly changing climates, where algae must evolve to survive shifting temperatures, salinity levels, and light conditions. For researchers, studying these adaptive mechanisms offers insights into combating climate change, as algae’s ability to sequester carbon and produce biofuels hinges on their spore-driven resilience.

In essence, spores are not just a means of reproduction for algae but a multifaceted tool for survival. They encapsulate the organism’s ability to withstand adversity, spread across uncharted territories, and evolve in response to environmental pressures. Whether in a laboratory, an aquarium, or the wild, understanding the role of spores in algae provides a deeper appreciation for these organisms’ ecological significance and their potential applications in science and industry.

Buying Death Cap Spores: Legal, Ethical, and Safety Concerns Explored

You may want to see also

Algae vs. Plants Spores: Algae spores differ from plant spores in structure, function, and life cycle stages

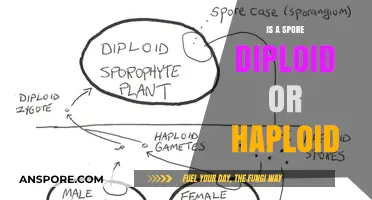

Algae and plant spores, though both reproductive units, exhibit distinct differences in structure, function, and life cycle stages. Algae spores, often referred to as zoospores or aplanospores, are typically unicellular and motile, equipped with flagella for movement in aquatic environments. In contrast, plant spores, such as those produced by ferns or mosses, are multicellular, non-motile, and adapted for dispersal through air or water currents. This fundamental structural disparity reflects their evolutionary divergence and ecological niches.

Consider the life cycle stages to understand their functional differences. Algae spores are part of a haplontic or diplontic life cycle, where the dominant phase is either haploid (e.g., in Chlorophyta) or diploid (e.g., in Rhodophyta). These spores directly develop into new individuals without an alternation of generations. Plant spores, however, are integral to an alternation of generations, where the haploid gametophyte and diploid sporophyte phases are both multicellular and free-living. For instance, fern spores grow into small gametophytes that produce eggs and sperm, which then form a new sporophyte. This complexity in plant life cycles contrasts sharply with the simpler, often unicellular development of algae spores.

From a practical perspective, these differences have implications for cultivation and control. Algae spores, due to their motility and rapid reproduction, can quickly colonize aquatic systems, making them both a boon for biotechnology (e.g., biofuel production) and a bane for water management (e.g., algal blooms). Plant spores, with their reliance on specific environmental cues for germination, are more predictable but require precise conditions for successful growth. For example, gardeners must ensure adequate moisture and light for fern spores to develop, whereas algae spores thrive in nutrient-rich water with minimal intervention.

To illustrate, compare the dispersal mechanisms. Algae spores often rely on water currents or self-propulsion to spread, making them highly effective in aquatic ecosystems. Plant spores, such as those of dandelions or ferns, are lightweight and aerodynamically shaped for wind dispersal. This adaptation allows plants to colonize diverse terrestrial habitats, whereas algae remain largely confined to water bodies. Understanding these mechanisms can inform strategies for both conservation and pest control, such as using barriers to prevent algal spread or optimizing airflow for plant spore germination.

In conclusion, while both algae and plant spores serve reproductive purposes, their structural, functional, and life cycle differences highlight distinct evolutionary strategies. Algae spores prioritize rapid, unicellular development in aquatic environments, whereas plant spores support complex, multicellular life cycles on land. Recognizing these disparities not only deepens our understanding of biology but also guides practical applications in agriculture, biotechnology, and environmental management.

Earthquakes and Spores: Unraveling the Myth of Seismic Fungal Release

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, algae are not spores. Algae are photosynthetic organisms that can be unicellular or multicellular, while spores are reproductive structures produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria.

Some types of algae, particularly certain species of green algae and red algae, produce spores as part of their life cycle. These spores are used for reproduction and dispersal.

While algae and spores are distinct, some algae use spores for reproduction. However, not all algae produce spores, and spores are not exclusive to algae, as they are also found in other organisms like fungi and plants.

Yes, in species of algae that produce spores, new algae can grow from these spores under suitable conditions. This is a common method of reproduction and dispersal in certain algal groups.