Pteridophytes, a diverse group of vascular plants, are indeed spore-producing organisms, setting them apart from seed-bearing plants. This group includes ferns, horsetails, and clubmosses, which reproduce through spores rather than seeds, a characteristic feature of their life cycle. Unlike flowering plants, pteridophytes do not produce flowers or fruits; instead, they release spores that develop into gametophytes, which then give rise to the next generation of plants. This method of reproduction is a key aspect of their biology and is essential for understanding their classification and evolutionary significance in the plant kingdom.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction | Spores (not seeds) |

| Life Cycle | Alternation of generations (sporophyte dominant) |

| Vascular Tissue | Present (xylem and phloem) |

| Roots | True roots (but often simple and unbranched) |

| Stems | Rhizomes, often underground |

| Leaves | Microphylls (small, single-veined) or megaphylls (large, complexly veined) |

| Examples | Ferns, horsetails, clubmosses |

| Seed Production | Absent |

| Flower Production | Absent |

| Habitat | Moist, shaded environments |

| Evolutionary Position | Primitive vascular plants, bridging bryophytes and seed plants |

| Spore Dispersal | Wind or water |

| Photosynthesis | Occurs in leaves (fronds in ferns) |

| Growth Form | Herbaceous, rarely woody |

| Fossil Record | Abundant in Paleozoic era (e.g., Carboniferous period) |

| Economic Importance | Ornamental plants, soil stabilization, medicinal uses |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Production Mechanisms: How pteridophytes produce and disperse spores for reproduction and survival

- Life Cycle Stages: Alternation of generations in pteridophytes, from sporophyte to gametophyte

- Spore Structure: Characteristics and adaptations of pteridophyte spores for longevity and dispersal

- Habitat and Spore Dispersal: Role of spores in colonizing diverse environments, from forests to wetlands

- Evolutionary Significance: Spore-based reproduction as a key trait in pteridophyte evolution and survival

Spore Production Mechanisms: How pteridophytes produce and disperse spores for reproduction and survival

Pteridophytes, a group of vascular plants including ferns, horsetails, and lycophytes, are indeed spore-producing plants. Their reproductive strategy hinges on the production and dispersal of spores, a mechanism that has ensured their survival for over 400 million years. Unlike seed plants, pteridophytes rely on an alternation of generations, where the sporophyte (spore-producing) and gametophyte (gamete-producing) phases are distinct and free-living. Understanding how these plants produce and disperse spores is key to appreciating their ecological resilience and evolutionary success.

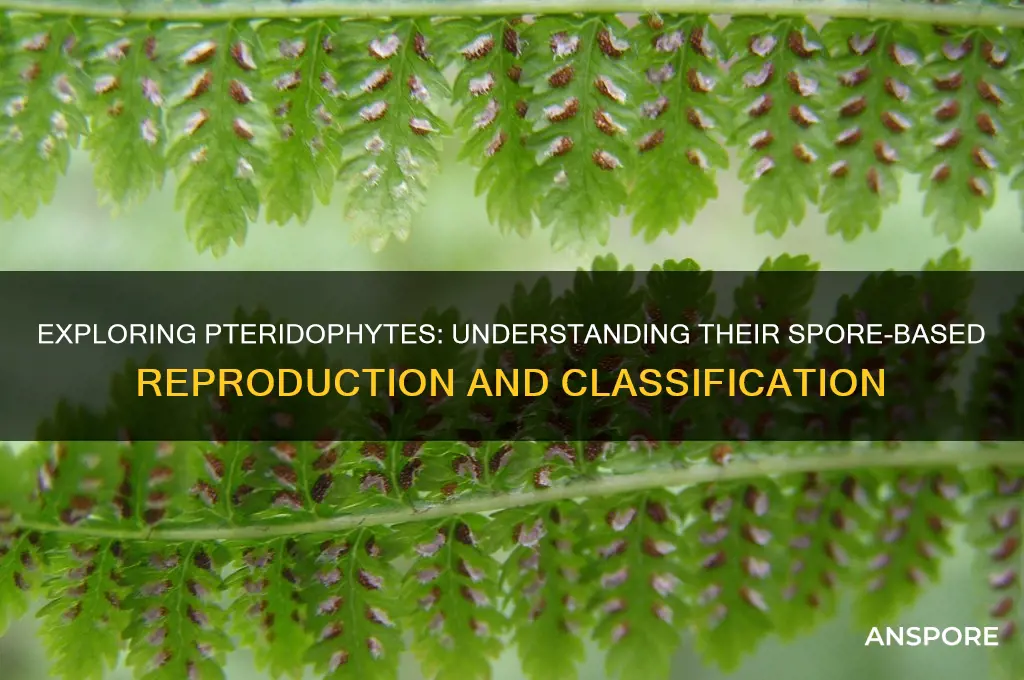

Spore production in pteridophytes begins in specialized structures called sporangia, typically located on the undersides of leaves or fronds. These sporangia develop from a single cell and mature into sac-like structures containing hundreds to thousands of spores. The process is highly regulated, with environmental cues such as light, humidity, and temperature influencing the timing and quantity of spore production. For example, many fern species release spores during dry, windy conditions to maximize dispersal. The sporangia often have intricate mechanisms, like the elastic annulus in leptosporangiate ferns, which aids in the forceful ejection of spores when conditions are optimal.

Dispersal of spores is a critical step in the pteridophyte life cycle, ensuring genetic diversity and colonization of new habitats. Spores are lightweight and often equipped with structures like elaters (in horsetails) or wings (in some lycophytes) that enhance their ability to travel on air currents. Once released, spores can be carried over long distances, though most settle within a few meters of the parent plant. This short-range dispersal is balanced by the sheer volume of spores produced, increasing the likelihood of finding suitable environments for germination. Water also plays a role in dispersal, particularly in moist habitats where spores can be washed into crevices or soil.

The survival of spores is another fascinating aspect of pteridophyte reproduction. Spores are highly resilient, capable of withstanding desiccation, extreme temperatures, and other harsh conditions. This dormancy allows them to persist in the environment until conditions are favorable for germination. Once a spore lands in a suitable location, it develops into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure that produces gametes. The gametophyte phase is dependent on moisture for fertilization, highlighting the importance of habitat selection in the spore dispersal process.

Practical observations of spore production and dispersal can be made by examining mature fern fronds under a magnifying glass, where sporangia appear as clusters of brown dots. For enthusiasts, collecting spores for propagation is straightforward: place a mature frond in a paper bag, and within days, spores will accumulate at the bottom. These spores can then be sown on a moist substrate to grow new gametophytes. Understanding these mechanisms not only deepens appreciation for pteridophytes but also informs conservation efforts, as many species are threatened by habitat loss and climate change. By studying their spore production and dispersal, we gain insights into the delicate balance that sustains these ancient plants in modern ecosystems.

Are Ivy Spores Harmful? Uncovering the Truth About Ivy Spores

You may want to see also

Life Cycle Stages: Alternation of generations in pteridophytes, from sporophyte to gametophyte

Pteridophytes, commonly known as ferns and their allies, are indeed spore plants, and their life cycle is a fascinating example of alternation of generations. This process involves two distinct phases: the sporophyte and the gametophyte, each with unique structures and functions. Understanding this cycle is crucial for anyone studying plant biology or cultivating these plants.

The Sporophyte Phase: Dominance and Spore Production

The sporophyte generation is the most visible and long-lived stage in pteridophytes. It is a diploid organism, meaning it has two sets of chromosomes. The sporophyte produces spores through structures called sporangia, typically located on the undersides of fern fronds. These spores are haploid, carrying a single set of chromosomes. The production of spores occurs via meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number. For example, in the common Bracken fern (*Pteridium aquilinum*), sporangia cluster into structures called sori, which release spores when mature. This phase is critical for dispersal, as spores are lightweight and can travel long distances by wind or water.

Transition to the Gametophyte: A Hidden but Vital Stage

Once released, spores germinate under suitable conditions of moisture and light to form the gametophyte generation. Unlike the sporophyte, the gametophyte is small, inconspicuous, and short-lived. It is a haploid organism that develops into a heart-shaped structure called a prothallus. The prothallus is typically 3–10 mm in size and requires a damp environment to survive. It produces both male (sperm) and female (egg) gametes. The sperm are flagellated and swim through a thin film of water to fertilize the egg, a process dependent on moisture. This stage highlights the pteridophyte's reliance on water for reproduction, a trait shared with other non-seed plants.

Fertilization and Return to the Sporophyte

After fertilization, the zygote develops into a new sporophyte, completing the life cycle. This transition is a critical step in alternation of generations. The young sporophyte remains attached to the gametophyte initially, drawing nutrients from it until it can photosynthesize independently. For instance, in the Maidenhair fern (*Adiantum*), the sporophyte grows rapidly once established, overshadowing the gametophyte. This phase underscores the interdependence of the two generations in the pteridophyte life cycle.

Practical Implications and Takeaways

Understanding the alternation of generations in pteridophytes has practical applications, especially in horticulture and conservation. For example, gardeners cultivating ferns must ensure consistent moisture to support gametophyte development and fertilization. In conservation, protecting habitats that maintain humidity is essential for preserving fern species. Additionally, this life cycle provides insights into the evolution of plants, as it represents an intermediate step between simpler algae and more complex seed plants. By studying pteridophytes, we gain a deeper appreciation for the diversity and adaptability of plant life cycles.

Unveiling the Truth: Does Moss Have Spores and How Do They Spread?

You may want to see also

Spore Structure: Characteristics and adaptations of pteridophyte spores for longevity and dispersal

Pteridophytes, a group of vascular plants that includes ferns, horsetails, and lycophytes, are indeed spore plants. Their reproductive strategy hinges on the production and dispersal of spores, which are remarkably adapted for both longevity and efficient dissemination. These adaptations are critical for the survival and propagation of pteridophytes in diverse environments, from tropical rainforests to arid landscapes.

One of the key characteristics of pteridophyte spores is their protective outer wall, composed of sporopollenin, a highly resistant biopolymer. This wall shields the spore’s genetic material from desiccation, UV radiation, and microbial attack, ensuring its viability over extended periods. For instance, spores of certain fern species can remain dormant in soil for decades, only germinating when conditions are optimal. This resilience is particularly advantageous in unpredictable habitats, where water availability and temperature fluctuate widely.

Dispersal mechanisms of pteridophyte spores are equally ingenious. Many species produce lightweight, single-celled spores that can be carried over long distances by wind. The shape and size of these spores—often less than 50 micrometers in diameter—maximize their aerodynamic potential. Additionally, some pteridophytes, like the filmy ferns (Hymenophyllaceae), have evolved elaters, spring-like structures that propel spores away from the parent plant when dry, enhancing dispersal efficiency. This combination of lightweight design and active mechanisms ensures that spores reach new, potentially favorable habitats.

Another adaptation is the biparental inheritance of spore traits. In heterosporous pteridophytes, such as water ferns (Salviniales), two types of spores are produced: megaspores, which develop into female gametophytes, and microspores, which develop into male gametophytes. This division of labor allows for specialized adaptations in each spore type. Megaspores, larger and nutrient-rich, are better suited for local colonization, while microspores, smaller and more numerous, are optimized for long-distance dispersal. This strategy increases the species’ adaptability to varying environmental conditions.

Practical observations of these adaptations can inform conservation efforts and horticulture. For example, when propagating ferns, gardeners should mimic natural dispersal by scattering spores on moist, well-drained soil and maintaining high humidity. Additionally, understanding spore longevity can aid in the restoration of degraded ecosystems, where dormant spores in the soil seed bank can be activated by appropriate environmental cues. By studying these characteristics, we gain insights into the evolutionary success of pteridophytes and tools for their preservation.

Exploring Fungal Spores: Are They Found on Sporangium Structures?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Habitat and Spore Dispersal: Role of spores in colonizing diverse environments, from forests to wetlands

Pteridophytes, a group of vascular plants that includes ferns, horsetails, and lycophytes, are indeed spore plants. Unlike seed plants, they rely on spores for reproduction and dispersal, a strategy that has allowed them to colonize a remarkable range of habitats, from dense forests to waterlogged wetlands. This adaptability hinges on the unique characteristics of spores—lightweight, resilient, and capable of surviving in diverse environmental conditions. Understanding how spores function in habitat colonization reveals the evolutionary success of pteridophytes and their ecological significance.

Consider the process of spore dispersal in a forest ecosystem. When a fern releases spores from the undersides of its fronds, these microscopic units are carried by wind currents, often traveling significant distances. Upon landing in a suitable microhabitat—a damp, shaded area with organic matter—the spores germinate into gametophytes, the sexual stage of the plant’s life cycle. This stage is critical, as it requires moisture for fertilization, highlighting why forests with their high humidity and canopy cover are ideal. However, the spore’s ability to remain dormant for extended periods ensures that even if conditions are temporarily unfavorable, colonization can occur when the environment shifts.

In contrast, wetlands present a different set of challenges and opportunities for spore dispersal. Here, water acts as both a medium and a barrier. Spores released near water bodies can be transported by surface currents, allowing pteridophytes to colonize distant areas within the wetland. For example, species like the marsh fern (*Thelypteris palustris*) thrive in these conditions, their spores dispersing effectively in shallow, slow-moving water. However, the constant moisture also increases the risk of fungal pathogens, which spores must resist to ensure successful germination. This dual role of water—as both facilitator and threat—underscores the spore’s adaptability in wetland colonization.

Practical observations of spore dispersal in diverse environments reveal actionable insights. For instance, gardeners cultivating ferns in humid, shaded areas can mimic forest conditions by maintaining consistent moisture levels and using organic mulch to support gametophyte development. In wetland restoration projects, introducing spore-bearing pteridophytes can enhance biodiversity, but care must be taken to ensure spores are sourced from compatible ecosystems to avoid invasive spread. Monitoring spore viability—through simple tests like germination rates under controlled conditions—can provide valuable data for conservation efforts.

Ultimately, the role of spores in colonizing diverse environments highlights the resilience and efficiency of pteridophytes’ reproductive strategy. Whether in the understory of a forest or the heart of a wetland, spores leverage environmental factors to their advantage, ensuring the survival and spread of these ancient plants. By studying their dispersal mechanisms, we gain not only ecological insights but also practical tools for conservation and horticulture, reinforcing the importance of spores in shaping plant communities across habitats.

Optimal Autoclave Spore Testing Frequency for Reliable Sterilization Results

You may want to see also

Evolutionary Significance: Spore-based reproduction as a key trait in pteridophyte evolution and survival

Pteridophytes, a group of vascular plants including ferns, horsetails, and lycophytes, are indeed spore plants. This fundamental characteristic of spore-based reproduction has been pivotal in their evolutionary journey and continued survival. Unlike seed plants, which rely on seeds for reproduction, pteridophytes produce spores that can disperse over vast distances, ensuring their presence in diverse and often challenging environments. This adaptability has allowed them to thrive for over 400 million years, even as ecosystems have undergone dramatic changes.

One of the key evolutionary advantages of spore-based reproduction lies in its efficiency and resilience. Spores are lightweight and can be carried by wind or water, enabling pteridophytes to colonize new habitats rapidly. For instance, ferns often dominate forest understories and rocky crevices, areas where seed-based reproduction might struggle due to limited soil or light. Additionally, spores can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh conditions such as droughts or frosts, only to germinate when conditions improve. This dormancy mechanism acts as a biological insurance policy, ensuring the species’ continuity even in unpredictable environments.

From a comparative perspective, spore-based reproduction offers pteridophytes a unique edge over seed plants in certain niches. While seeds require more energy to produce and are heavier, spores are produced in vast quantities with minimal energy investment. This strategy allows pteridophytes to allocate resources to other survival mechanisms, such as developing extensive root systems or chemical defenses. For example, horsetails (Equisetum) produce silica-rich tissues that deter herbivores, a trait that complements their spore-based reproductive strategy. This combination of traits highlights how spore reproduction has shaped pteridophytes into highly specialized and resilient organisms.

To understand the practical significance of this trait, consider the role of pteridophytes in ecosystem restoration. Their ability to disperse spores widely makes them ideal candidates for rehabilitating degraded lands. In areas affected by deforestation or mining, ferns and lycophytes can quickly establish themselves, preventing soil erosion and creating conditions suitable for other plant species. For instance, in tropical regions, ferns are often the first plants to colonize lava flows or landslide scars, paving the way for more complex vegetation. This underscores the evolutionary brilliance of spore-based reproduction—it not only ensures the survival of pteridophytes but also contributes to the health and stability of ecosystems.

In conclusion, spore-based reproduction is not merely a defining trait of pteridophytes but a cornerstone of their evolutionary success. Its efficiency, resilience, and adaptability have allowed these plants to persist through geological epochs, occupy diverse habitats, and play critical ecological roles. By studying this reproductive strategy, we gain insights into the mechanisms of survival and the enduring legacy of life’s earliest innovations. Pteridophytes remind us that sometimes, the simplest strategies can yield the most profound results.

Moss Spores vs. Sporangium: Unraveling the Tiny Reproductive Structures

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, pteridophytes are spore plants. They reproduce via spores rather than seeds, which is a defining characteristic of this group.

Pteridophytes produce spores in structures called sporangia, typically located on the undersides of their leaves (fronds). These spores are released and develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes for sexual reproduction.

Examples of pteridophytes include ferns, horsetails, and clubmosses. These plants are vascular but lack flowers and seeds, relying on spores for reproduction.

Pteridophytes are considered primitive because they reproduce via spores, lack seeds, and have a dominant sporophyte generation. These traits are characteristic of earlier plant evolutionary stages.