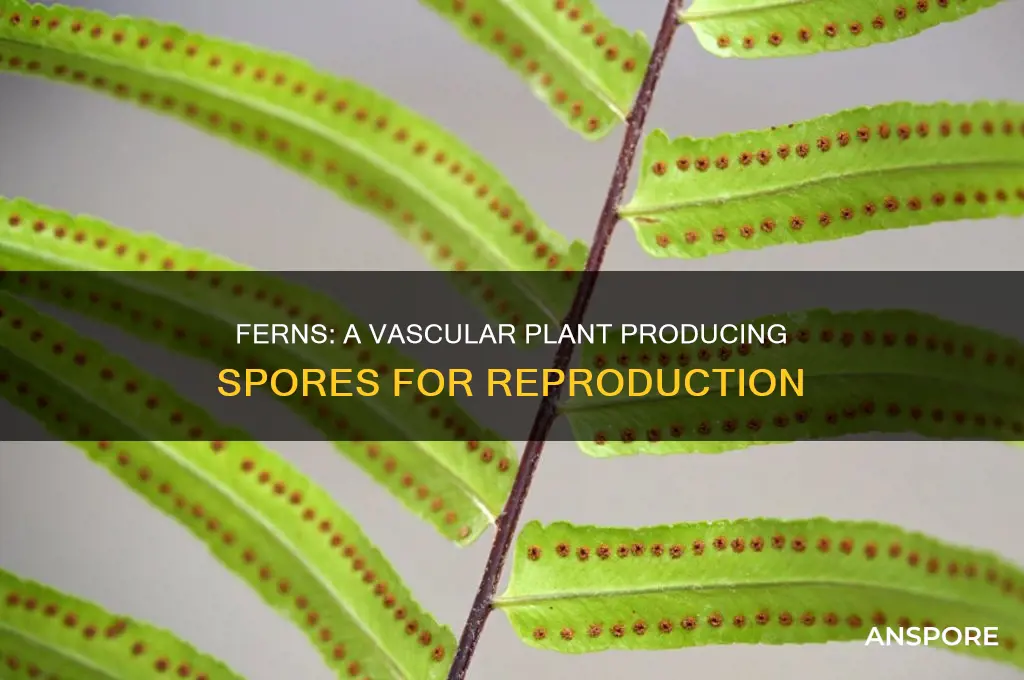

Ferns are a prime example of vascular plants that produce spores, distinguishing them from seed-bearing plants. Unlike flowering plants that reproduce through seeds, ferns rely on a unique life cycle involving alternation of generations, where they produce spores that develop into small, heart-shaped gametophytes. These gametophytes then release sperm and eggs, which, when fertilized, grow into the familiar fern plant. This reproductive strategy, combined with their vascular system for efficient nutrient and water transport, highlights ferns as a fascinating and ancient group of plants that have thrived for millions of years.

What You'll Learn

Ferns: Ancient vascular plants

Ferns, with their delicate fronds and ancient lineage, are a testament to the enduring success of vascular plants that reproduce via spores. Unlike seed-producing plants, ferns rely on a two-stage life cycle involving alternating generations: a spore-producing sporophyte and a gamete-producing gametophyte. This reproductive strategy, while complex, has allowed ferns to thrive for over 300 million years, predating even the dinosaurs. Their ability to colonize diverse habitats, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands, underscores their adaptability and resilience.

To cultivate ferns successfully, consider their preference for moist, shaded environments. They thrive in soil rich in organic matter with a pH between 5.5 and 6.5. For indoor ferns, maintain humidity by misting leaves daily or placing the pot on a tray of water-soaked pebbles. Outdoor ferns benefit from mulching to retain soil moisture. Avoid over-fertilization; a diluted liquid fertilizer applied monthly during the growing season suffices. Prune yellowing fronds to encourage new growth and improve air circulation, reducing the risk of fungal diseases.

One of the most fascinating aspects of ferns is their role in ecological systems. As vascular plants, they efficiently transport water and nutrients, contributing to soil stability and moisture retention. Their spore-producing nature allows for rapid colonization of disturbed areas, making them pioneers in forest regeneration. For instance, the Bracken fern (*Pteridium aquilinum*) is a prolific colonizer of burned or cleared lands, though its aggressive growth can sometimes outcompete native species. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for conservation efforts and sustainable land management.

Comparatively, ferns offer a unique aesthetic in landscaping and interior design. Their feathery fronds and varied textures create visual interest, contrasting sharply with broad-leaved plants. Species like the Boston fern (*Nephrolepis exaltata*) and Maidenhair fern (*Adiantum spp.*) are popular choices for indoor spaces due to their elegance and low maintenance requirements. In outdoor gardens, ferns can serve as ground cover or focal points in shaded areas, providing a lush, prehistoric ambiance. Their ability to thrive in low-light conditions makes them ideal for areas where other plants struggle.

In conclusion, ferns exemplify the ingenuity of nature’s design as ancient vascular plants that produce spores. Their dual life cycle, ecological significance, and aesthetic appeal make them a subject of both scientific interest and practical utility. Whether you’re a gardener, ecologist, or simply an admirer of natural beauty, ferns offer a wealth of opportunities for exploration and appreciation. By understanding their needs and roles, we can better integrate these timeless plants into our environments and preserve their legacy for future generations.

Perfect Spore Solution Dosage for Optimal Cake Colonization Results

You may want to see also

Clubmosses: Small spore-producing plants

Clubmosses, often overlooked in the plant kingdom, are a fascinating group of small, spore-producing vascular plants that have been around for over 400 million years. Unlike their more prominent relatives, ferns and flowering plants, clubmosses (Lycopodiopsida) thrive in diverse habitats, from moist woodlands to rocky outcrops. Their diminutive size belies their ecological significance, as they play a crucial role in soil stabilization and nutrient cycling. These plants are characterized by their simple, branching stems and microphylls (small, single-veined leaves), which give them a distinctive, almost prehistoric appearance. Despite their ancient lineage, clubmosses remain relevant today, offering insights into plant evolution and serving as a reminder of the resilience of early land plants.

One of the most intriguing aspects of clubmosses is their reproductive strategy. Unlike seed-producing plants, clubmosses rely on spores for reproduction, a trait they share with ferns and other non-seed vascular plants. Their spores are produced in structures called strobili, which are often club-shaped, giving the group its common name. These strobili are typically found at the tips of branches and release spores into the wind for dispersal. Interestingly, clubmoss spores are not only a means of reproduction but also have historical significance. For instance, *Lycopodium clavatum*, a common species, produces spores that were once used as a flash powder in photography due to their highly flammable nature. This dual role—both biological and practical—highlights the versatility of these tiny plants.

From a horticultural perspective, clubmosses are low-maintenance plants that can add a unique texture to shade gardens or terrariums. They prefer moist, well-drained soil and indirect light, making them ideal for woodland gardens or as ground cover in cooler climates. When cultivating clubmosses, it’s essential to avoid overwatering, as their shallow root systems are susceptible to rot. Propagation is best achieved through division of established clumps in spring or by sowing spores, though the latter requires patience, as spore germination can be slow and unpredictable. For enthusiasts looking to incorporate clubmosses into their gardens, species like *Lycopodium japonicum* or *Huperzia lucidula* are excellent choices due to their hardiness and aesthetic appeal.

Comparatively, clubmosses offer a stark contrast to more familiar vascular plants like ferns and flowering plants. While ferns often dominate shaded areas with their large, feathery fronds, clubmosses contribute a finer, more delicate texture to the understory. Their spore-producing method also sets them apart from seed plants, which have evolved more complex reproductive strategies. However, this simplicity does not diminish their importance; rather, it underscores their adaptability and longevity. In ecosystems where larger plants struggle, clubmosses often thrive, demonstrating their ability to exploit niche environments. This resilience makes them valuable subjects for studying plant survival strategies in challenging conditions.

In conclusion, clubmosses are a testament to the diversity and adaptability of vascular plants that produce spores. Their small size, ancient lineage, and unique reproductive methods make them a fascinating subject for both botanists and gardeners. Whether appreciated for their ecological role, historical uses, or aesthetic qualities, clubmosses deserve recognition as more than just relics of the past. By understanding and cultivating these plants, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate web of life that sustains our planet’s ecosystems.

Preserve Your Spore Creations: Easy Offline Saving Guide

You may want to see also

Horsetails: Hollow-stemmed vascular species

Horsetails, scientifically known as *Equisetum*, are a living relic of ancient plant lineages, offering a unique glimpse into the evolution of vascular plants. Their hollow stems, a defining feature, are not merely structural but serve as a testament to their efficient adaptation over millennia. Unlike the solid stems of many modern plants, the hollow design of horsetails allows for lightweight yet sturdy growth, enabling them to thrive in diverse environments, from wetlands to woodlands. This anatomical peculiarity is a key factor in their resilience, making them one of the few surviving genera of a once-dominant plant group.

To cultivate horsetails successfully, consider their preference for moist, sandy soils rich in silica, a mineral they absorb in high quantities. This silica accumulation contributes to their rigid structure and is a notable characteristic distinguishing them from other vascular plants. For gardeners, planting horsetails near water features or in consistently damp areas can mimic their natural habitat. However, caution is advised: their aggressive rhizomatous growth can quickly invade neighboring plants, so containment within barriers or pots is recommended. Regular monitoring and division of clumps every 2–3 years can prevent overgrowth while maintaining their health.

From a comparative perspective, horsetails stand apart from other spore-producing vascular plants, such as ferns, due to their jointed stems and whip-like appearance. While ferns rely on fronds for photosynthesis, horsetails utilize their green stems as primary photosynthetic organs, with reduced leaves forming sheath-like structures around the stem nodes. This distinction highlights their evolutionary specialization, which has allowed them to occupy ecological niches inaccessible to other plants. Their ability to produce spores in cone-like structures at the tips of fertile stems further underscores their unique reproductive strategy, bridging the gap between ancient and modern plant forms.

For those intrigued by their historical significance, horsetails have been used traditionally for their abrasive qualities, owing to their high silica content. In practical applications, dried stems can be employed as natural scouring tools for cleaning pots or smoothing wood. However, their consumption is not advised, as some species contain toxic alkaloids. Instead, their value lies in their ecological role as indicators of wetland health and their educational potential in demonstrating the diversity of plant adaptations. By studying horsetails, enthusiasts and researchers alike can gain deeper insights into the mechanisms that have sustained life on Earth for over 300 million years.

Growing Ostrich Ferns from Spores: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Whisk ferns: Simple vascular structures

Whisk ferns, belonging to the genus *Psilotum*, are living fossils that defy conventional plant anatomy. Unlike most vascular plants, they lack true roots, leaves, and seeds, yet they thrive in tropical and subtropical regions. Their vascular system, though simple, is remarkably efficient, consisting of a central stele with xylem and phloem arranged in a rudimentary pattern. This minimal structure allows whisk ferns to transport water and nutrients effectively, showcasing the elegance of evolutionary simplicity.

To cultivate whisk ferns, consider their epiphytic nature—they often grow on tree bark or rocks in humid environments. Provide a well-draining substrate like orchid bark mixed with sphagnum moss, and maintain high humidity levels around 70-80%. Water sparingly but consistently, ensuring the substrate never fully dries out. These plants are sensitive to overwatering, so monitor moisture levels closely. For optimal growth, place them in bright, indirect light, mimicking their natural understory habitat.

Comparatively, whisk ferns stand apart from other spore-producing vascular plants like ferns and lycophytes. While ferns exhibit complex fronds and lycophytes have microphylls, whisk ferns present as dichotomously branching stems with tiny, scale-like structures called enations. This stark contrast highlights their evolutionary divergence and underscores their role as a bridge between non-vascular and more complex vascular plants. Their simplicity makes them an ideal subject for studying the origins of vascular tissue in plants.

A persuasive argument for preserving whisk ferns lies in their ecological and scientific value. As primitive vascular plants, they offer insights into the transition from non-vascular to vascular plant life. Their ability to survive in nutrient-poor environments also makes them indicators of ecosystem health. Conservation efforts should focus on protecting their natural habitats, particularly tropical forests, and promoting their cultivation in botanical gardens to safeguard their genetic diversity.

In conclusion, whisk ferns exemplify the beauty of simplicity in vascular plant evolution. Their unique structure, cultivation needs, and ecological significance make them a fascinating subject for botanists and hobbyists alike. By understanding and appreciating these ancient plants, we gain a deeper insight into the diversity and resilience of plant life on Earth.

Achieve Borderless Spore Gameplay: Simple Windowed Mode Setup Guide

You may want to see also

Quillworts: Aquatic spore-bearing plants

Quillworts, scientifically known as *Isoetes*, are a fascinating group of aquatic and semi-aquatic plants that defy conventional expectations of vascular flora. Unlike most vascular plants that produce seeds, quillworts reproduce via spores, a trait more commonly associated with non-vascular plants like ferns and mosses. This unique combination of vascular tissue and spore-bearing reproduction places quillworts at an evolutionary crossroads, offering insights into the transition from simpler to more complex plant forms. Their ability to thrive in diverse aquatic environments, from freshwater ponds to cold mountain streams, underscores their adaptability and ecological significance.

To identify quillworts in the wild, look for their distinctive, quill-like leaves that emerge from a central corm. These leaves are not true leaves in the botanical sense but rather modified structures called microphylls, each bearing sporangia where spores develop. The spores themselves are dimorphic: megaspores, which grow into female gametophytes, and microspores, which develop into male gametophytes. This reproductive strategy ensures genetic diversity and resilience in varying environmental conditions. For enthusiasts or researchers, collecting and observing these spores under a microscope can reveal their intricate structures and life cycles, making quillworts an excellent subject for botanical study.

From a conservation perspective, quillworts are indicators of water quality and ecosystem health. Their presence often signifies clean, unpolluted aquatic environments, as they are sensitive to contaminants like heavy metals and excessive nutrients. However, habitat destruction, water pollution, and invasive species pose significant threats to their survival. Efforts to protect quillworts should include monitoring water quality, restoring degraded habitats, and raising awareness about their ecological importance. For instance, in regions where *Isoetes* species are endangered, such as certain parts of North America and Europe, targeted conservation programs can help prevent their decline.

Cultivating quillworts in aquariums or water gardens can be a rewarding endeavor for hobbyists. To successfully grow them, ensure the substrate is rich in organic matter, such as sand mixed with peat or clay. Maintain a water depth of 6–12 inches, and provide moderate light conditions to mimic their natural habitat. Avoid over-fertilization, as quillworts are adapted to nutrient-poor environments. Regularly inspect the plants for signs of stress, such as yellowing leaves or reduced spore production, which may indicate poor water quality or inadequate conditions. With proper care, quillworts can become a striking and educational addition to any aquatic collection.

In conclusion, quillworts exemplify the diversity and complexity of vascular plants that produce spores. Their evolutionary uniqueness, ecological role, and potential for cultivation make them a subject of both scientific and practical interest. By understanding and appreciating these aquatic spore-bearing plants, we not only gain insights into plant biology but also contribute to their conservation and sustainable enjoyment. Whether in the wild or in a controlled setting, quillworts remind us of the intricate connections between form, function, and environment in the natural world.

Planting Ancient Fern Spores: A Step-by-Step Guide to Revival

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Ferns are a classic example of vascular plants that produce spores.

Vascular plants like ferns produce spores in structures called sporangia, typically located on the undersides of their leaves (fronds).

No, not all vascular plants produce spores. While ferns and other pteridophytes do, seed plants like gymnosperms and angiosperms reproduce via seeds, not spores.

Spores are the reproductive units in the life cycle of vascular plants like ferns. They develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes for sexual reproduction.

No, vascular plants that produce spores, such as ferns, do not produce seeds. Seed production is a characteristic of more advanced vascular plants like gymnosperms and angiosperms.