Mushrooms, as fungi, reproduce through the release of spores, but the question of whether this process is sexual or asexual depends on the type of spores and the life cycle stage. Fungi can produce both asexual spores, such as conidia, which are formed through mitosis and allow for rapid reproduction, and sexual spores, such as basidiospores or asci, which result from meiosis and genetic recombination. In mushrooms, the most commonly observed spores are typically sexual, produced during the fruiting body stage through the fusion of haploid cells and subsequent meiosis. This sexual reproduction promotes genetic diversity and adaptability, making it a crucial aspect of fungal survival and evolution. Understanding whether mushroom spore production is sexual or asexual requires examining the specific fungal species and its reproductive mechanisms.

| Characteristics | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of Reproduction | Both sexual and asexual | |

| Sexual Reproduction | Involves the fusion of haploid nuclei from two compatible mycelia, forming a diploid zygote that develops into a basidium (in basidiomycetes) or an ascus (in ascomycetes), which then produces spores (meiosis involved) | |

| Asexual Reproduction | Occurs through vegetative means like fragmentation, budding, or asexual spores (e.g., conidia, chlamydospores) without nuclear fusion or meiosis | |

| Spores Produced | Sexual: Meiospores (basidiospores, ascospores) | Asexual: Mitospores (conidia, chlamydospores, etc.) |

| Genetic Diversity | Sexual: High (recombination of genetic material) | Asexual: Low (clonal, no genetic recombination) |

| Energy Investment | Sexual: Higher (requires compatible partners and complex structures) | Asexual: Lower (rapid and efficient) |

| Environmental Adaptation | Sexual: Better for long-term survival and adaptation | Asexual: Better for rapid colonization in stable environments |

| Examples | Sexual: Most mushroom-forming fungi (e.g., Agaricus bisporus) | Asexual: Molds like Penicillium, some mushroom fungi under stress |

| Role in Life Cycle | Sexual: Primary for reproduction and genetic diversity | Asexual: Secondary, often for survival or dispersal |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Methods: Mushrooms release spores via gills, pores, or teeth, often aided by wind or water

- Sexual Spores (Meiospores): Formed through meiosis, combining genetic material from two parents for diversity

- Asexual Spores (Mitospores): Produced by mitosis, cloning the parent fungus without genetic variation

- Basidiospores: Sexual spores produced on basidia, common in most mushroom-forming fungi

- Environmental Triggers: Sporulation is influenced by humidity, light, temperature, and nutrient availability

Sporulation Methods: Mushrooms release spores via gills, pores, or teeth, often aided by wind or water

Mushrooms employ various sporulation methods to release spores, primarily through structures like gills, pores, or teeth. These methods are essential for their reproductive cycle, which can be either sexual or asexual, depending on the species and environmental conditions. The release of spores is a critical step in the mushroom's life cycle, ensuring the dispersal of genetic material and the colonization of new habitats. Gills, found on the underside of the cap in many mushroom species, are thin, blade-like structures that provide a large surface area for spore production. As the mushroom matures, spores are formed on the gills and are eventually released into the environment. This process is often facilitated by air currents, which carry the lightweight spores to new locations.

Pores, another common sporulation structure, are found in mushrooms belonging to the genus *Boletus* and others. Instead of gills, these mushrooms have a spongy layer of tubes that open to the exterior as small pores. Spores are produced within these tubes and are released through the pores, often in a more controlled manner compared to gills. Water can play a significant role in spore dispersal for pored mushrooms, as raindrops falling on the cap can dislodge spores and carry them away. This method ensures that spores are distributed over a wider area, increasing the chances of successful colonization.

Toothed mushrooms, such as those in the genus *Hydnum*, have a unique sporulation method. Instead of gills or pores, they possess spines or teeth on the underside of the cap, which bear the spores. These teeth provide a surface for spore production, and the spores are released as the mushroom matures. Wind is a primary agent in dispersing spores from toothed mushrooms, as it can easily carry the spores away from the parent mushroom. This method is particularly effective in open environments where air movement is consistent.

The role of wind and water in spore dispersal cannot be overstated. Wind is a dominant force in carrying spores over long distances, especially for mushrooms with gills or teeth, which produce spores that are lightweight and easily airborne. Water, on the other hand, is more crucial for pored mushrooms, where raindrops or splashes can dislodge spores and transport them to new locations. Both elements work in tandem with the mushroom's sporulation structures to ensure efficient and widespread dispersal.

Understanding these sporulation methods is key to determining whether mushroom spore production is sexual or asexual. In most cases, the spores produced via gills, pores, or teeth are the result of sexual reproduction, involving the fusion of gametes and the formation of a diploid zygote. However, some mushrooms can also produce spores asexually through processes like fragmentation or budding, though this is less common. The primary mode of spore production in mushrooms is sexual, and the structures (gills, pores, teeth) are highly adapted to maximize the efficiency of spore release and dispersal, often with the aid of natural elements like wind and water.

In summary, mushrooms release spores through specialized structures—gills, pores, or teeth—each adapted to their specific environment and dispersal needs. These methods are predominantly sexual, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability. The involvement of wind and water in spore dispersal highlights the intricate relationship between mushrooms and their environment, facilitating their survival and propagation across diverse ecosystems.

Mushroom Mystery: Black Interior Explained

You may want to see also

Sexual Spores (Meiospores): Formed through meiosis, combining genetic material from two parents for diversity

Mushrooms, like many fungi, produce spores as part of their reproductive cycle. Among these, sexual spores, also known as meiospores, play a crucial role in genetic diversity. These spores are formed through the process of meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, creating haploid cells. This process is fundamentally different from asexual spore production, which involves mitosis and results in genetically identical offspring. In mushrooms, meiosis occurs in specialized structures called basidia (in basidiomycetes) or asci (in ascomycetes), where genetic material from two parent nuclei is combined and then divided to form spores with unique genetic combinations.

The formation of sexual spores begins with the fusion of two compatible haploid hyphae, a process known as plasmogamy. This is followed by karyogamy, where the nuclei of the two parents merge, creating a diploid cell. This diploid cell then undergoes meiosis, producing four haploid nuclei. Each of these nuclei migrates into a developing spore, resulting in spores that carry a mix of genetic material from both parents. This genetic recombination is essential for the survival and adaptation of mushroom species, as it allows them to respond to changing environments and resist diseases.

One of the key advantages of sexual spores is their ability to introduce genetic diversity. Unlike asexual spores, which are clones of the parent organism, meiospores inherit a unique combination of traits from two parents. This diversity is critical for the long-term success of mushroom populations, as it increases the likelihood that some individuals will possess traits advantageous for survival in varying conditions. For example, genetic variation can lead to differences in spore dispersal mechanisms, resistance to pathogens, or the ability to colonize new habitats.

The production of sexual spores is often tied to specific environmental cues, such as changes in temperature, humidity, or light. These cues signal the fungus to initiate the sexual reproductive cycle, ensuring that spores are released under conditions favorable for germination and growth. In mushrooms, this typically involves the development of fruiting bodies (the visible mushroom structure), which serve as the site for meiosis and spore formation. The release of these spores into the environment marks the culmination of the sexual reproductive process, allowing the fungus to disperse and colonize new areas.

In summary, sexual spores (meiospores) in mushrooms are formed through meiosis, a process that combines genetic material from two parents to create genetically diverse offspring. This mechanism is essential for the adaptability and survival of fungal species, as it fosters variation and resilience in changing environments. Understanding the distinction between sexual and asexual spore production highlights the complexity and sophistication of fungal reproductive strategies, underscoring their importance in ecosystems worldwide.

Mushroom Magic: Unveiling the Dirty Trich's Secrets

You may want to see also

Asexual Spores (Mitospores): Produced by mitosis, cloning the parent fungus without genetic variation

Mushrooms, like many fungi, produce spores as a means of reproduction. Among these, asexual spores, also known as mitospores, play a crucial role in the fungal life cycle. These spores are produced through the process of mitosis, a type of cell division that results in genetically identical daughter cells. Unlike sexual reproduction, which involves the fusion of gametes and genetic recombination, asexual spore production is a form of cloning. This means that the spores inherit the exact genetic material of the parent fungus, without any variation. Mitospores are therefore a direct and efficient way for fungi to reproduce rapidly under favorable conditions, ensuring the survival and spread of the species without the need for a mate.

The production of asexual spores occurs in specialized structures such as conidia or sporangiospores, depending on the fungal species. For example, molds like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium* produce conidia on structures called conidiophores. These spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by air or water, allowing the fungus to colonize new environments quickly. Because mitospores are genetically identical to the parent, they are well-suited for environments where the fungus is already thriving. However, this lack of genetic diversity can be a limitation in changing or challenging conditions, as the spores may not possess the traits needed to adapt to new stressors.

One of the key advantages of asexual spore production is its speed and efficiency. Mitosis is a relatively fast process compared to the complex steps involved in sexual reproduction, such as meiosis and fertilization. This allows fungi to produce large quantities of spores in a short time, maximizing their chances of survival and dispersal. Additionally, asexual reproduction does not require the energy investment needed to produce specialized reproductive structures like fruiting bodies (e.g., mushrooms), which are typically associated with sexual reproduction. This makes mitospores particularly advantageous in stable, resource-rich environments.

Despite their efficiency, asexual spores have limitations. The absence of genetic variation means that populations of fungi reproducing asexually are more vulnerable to diseases, pests, or environmental changes. If a pathogen or adverse condition affects one individual, it is likely to affect all genetically identical offspring. This lack of diversity also reduces the potential for evolution and adaptation over time. Therefore, while asexual spores are a successful reproductive strategy in the short term, many fungi also engage in sexual reproduction to ensure long-term survival and genetic resilience.

In summary, asexual spores (mitospores) are a vital component of fungal reproduction, produced through mitosis to clone the parent fungus without introducing genetic variation. This method is fast, efficient, and well-suited for rapid colonization of favorable environments. However, the lack of genetic diversity limits adaptability and long-term survival in changing conditions. Understanding the role of asexual spores in the fungal life cycle highlights the balance between efficiency and resilience in the reproductive strategies of mushrooms and other fungi.

Boost Libido with These Magical Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Explore related products

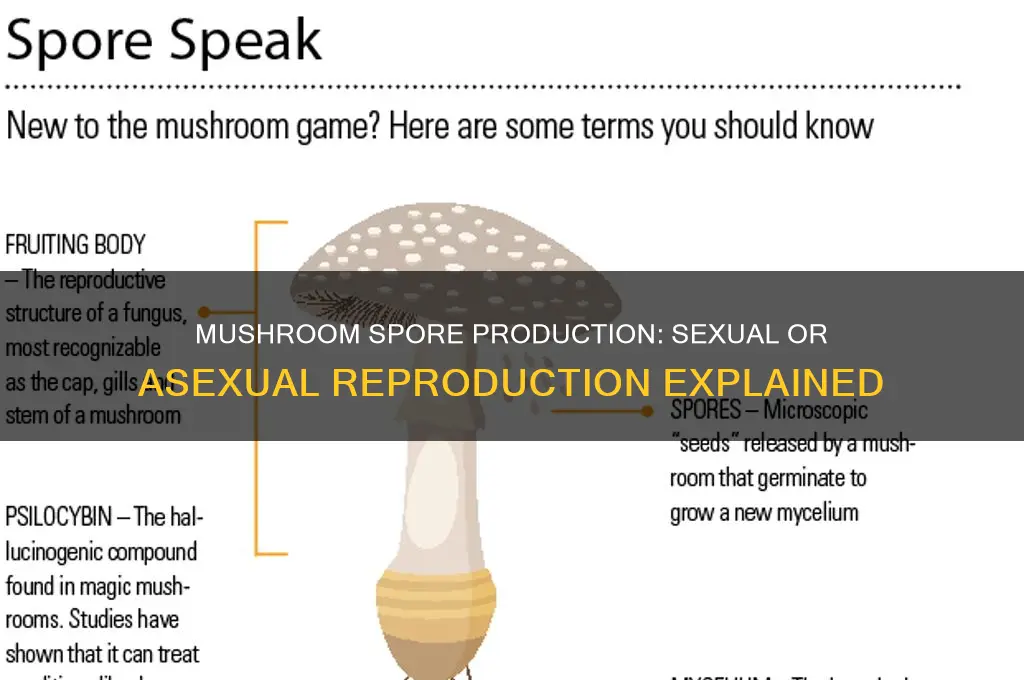

Basidiospores: Sexual spores produced on basidia, common in most mushroom-forming fungi

Mushrooms, like many fungi, produce spores as part of their reproductive cycle. The question of whether these spores are produced sexually or asexually depends on the type of spore and the fungal species in question. Among the various types of spores, basidiospores are of particular interest because they are sexual spores produced by most mushroom-forming fungi. These spores are formed on specialized structures called basidia, which are club-shaped cells typically found on the gills, pores, or teeth of mushrooms. Understanding basidiospores is crucial to grasping the sexual reproduction process in these fungi.

Basidiospores are the result of a complex sexual reproductive cycle known as meiosis, which involves the fusion of haploid cells (gametes) from two compatible individuals. This process begins when hyphae (thread-like structures of the fungus) from two different mating types come into contact and fuse, forming a dikaryotic mycelium. This dikaryotic phase is unique to basidiomycetes and involves the coexistence of two haploid nuclei within the same cell. As the mushroom fruiting body develops, basidia are formed, each containing a pair of haploid nuclei. These nuclei fuse, followed by meiosis, which produces four haploid nuclei. Each nucleus then migrates into a basidiospore, which matures and is eventually released into the environment.

The production of basidiospores is a hallmark of basidiomycetes, the fungal division that includes most mushroom-forming species. This sexual mode of reproduction ensures genetic diversity, which is essential for the survival and adaptation of fungal populations. Once released, basidiospores can disperse via wind, water, or animals, germinating under suitable conditions to form new haploid mycelia. If these mycelia encounter compatible mates, the cycle repeats, leading to the formation of new fruiting bodies and the continuation of the species.

In contrast to basidiospores, some fungi produce asexual spores, such as conidia, which are formed through mitosis without the involvement of genetic recombination. However, basidiospores are distinctly sexual in nature, as they arise from meiosis and genetic mixing. This distinction is critical for understanding fungal biology, as it highlights the different strategies fungi employ to reproduce and propagate. While asexual spores allow for rapid multiplication in stable environments, sexual spores like basidiospores provide the genetic variability needed to adapt to changing conditions.

In summary, basidiospores are sexual spores produced on basidia, a process common in most mushroom-forming fungi. Their formation involves meiosis and genetic recombination, ensuring diversity within fungal populations. This contrasts with asexual spores, which lack genetic mixing. By studying basidiospores, we gain insight into the intricate reproductive strategies of fungi and their role in maintaining ecological balance. For anyone interested in mycology, understanding basidiospores is fundamental to appreciating the complexity and importance of fungal life cycles.

Frying Mushrooms: Tips for a Perfect Sizzle

You may want to see also

Environmental Triggers: Sporulation is influenced by humidity, light, temperature, and nutrient availability

Mushrooms produce spores as a means of reproduction, and the process of sporulation can be either sexual or asexual, depending on the species and environmental conditions. Asexual sporulation, known as vegetative or mitotic spore production, occurs through mechanisms like fragmentation or budding, while sexual sporulation involves the fusion of gametes, resulting in genetically diverse spores. Regardless of the type, sporulation in mushrooms is significantly influenced by environmental triggers, including humidity, light, temperature, and nutrient availability. These factors act as cues that signal the optimal conditions for spore release, ensuring the survival and dispersal of the fungal species.

Humidity plays a critical role in triggering sporulation in mushrooms. High humidity levels are often necessary for the development and release of spores, as water is essential for the maturation of spore-bearing structures like gills or pores. In many species, a relative humidity above 85% is required for sporulation to occur. Insufficient moisture can hinder the process, leading to incomplete or aborted spore formation. Conversely, excessive humidity can promote the growth of competing microorganisms or cause spore clumping, reducing dispersal efficiency. Therefore, mushrooms have evolved to detect and respond to specific humidity ranges that optimize sporulation success.

Light is another environmental factor that influences sporulation in mushrooms. While fungi are not photosynthetic, they are sensitive to light, particularly in terms of wavelength and duration. Light acts as a signal for the developmental timing of sporulation, with many species requiring specific light conditions to initiate the process. For example, some mushrooms sporulate only in the presence of near-ultraviolet or blue light, which mimics natural daylight conditions. Light can also affect the orientation and structure of spore-bearing tissues, ensuring that spores are released in a manner that maximizes dispersal. In the absence of appropriate light cues, sporulation may be delayed or inhibited, highlighting its importance as an environmental trigger.

Temperature is a key regulator of sporulation in mushrooms, with different species having specific temperature ranges that promote spore production. Generally, temperatures between 20°C and 25°C (68°F and 77°F) are optimal for sporulation in many mushroom species, though this can vary widely depending on the fungus's ecological niche. Extreme temperatures, either too hot or too cold, can disrupt the sporulation process by affecting enzyme activity, membrane integrity, or metabolic pathways. Additionally, temperature fluctuations can serve as a cue for seasonal sporulation, allowing mushrooms to synchronize their reproductive cycles with environmental conditions that favor spore survival and germination.

Nutrient availability also plays a significant role in triggering sporulation in mushrooms. When nutrients become scarce, fungi may shift their energy from vegetative growth to reproductive structures as a survival strategy. This is particularly true for saprotrophic mushrooms, which decompose organic matter and rely on nutrient-rich substrates for growth. Adequate levels of carbon, nitrogen, and other essential elements are required for the development of spores and spore-bearing structures. In nutrient-limited conditions, mushrooms may prioritize sporulation to ensure genetic continuity and dispersal to new environments. Conversely, an abundance of nutrients may delay sporulation, as the fungus focuses on expanding its mycelial network.

In conclusion, sporulation in mushrooms, whether sexual or asexual, is a complex process regulated by multiple environmental triggers. Humidity, light, temperature, and nutrient availability act as critical cues that signal the optimal conditions for spore production and release. Understanding these factors not only sheds light on the reproductive strategies of fungi but also has practical applications in fields like agriculture, mycology, and conservation. By manipulating these environmental triggers, researchers and cultivators can enhance sporulation efficiency, improve mushroom yields, and study fungal ecology in greater detail.

White Mushrooms: Carb Content and Nutrition Facts

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushroom spore production can be both sexual and asexual, depending on the species and environmental conditions. Most mushrooms produce spores through a sexual process called meiosis, where genetic material from two parent cells combines to create genetically diverse spores. However, some mushrooms can also produce spores asexually through processes like fragmentation or budding.

Mushrooms produce spores sexually through a process involving the fusion of haploid cells (gametes) from two compatible individuals. This results in the formation of a diploid zygote, which then undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores. These spores are genetically unique and are released into the environment to grow into new fungal organisms.

Yes, some mushrooms can produce spores without a partner through asexual methods like vegetative propagation or spore formation via mitosis. This process does not involve genetic recombination and results in spores that are genetically identical to the parent fungus. However, this is less common than sexual spore production in most mushroom species.