Pollen, often referred to as the male gametophyte in seed plants, plays a crucial role in plant reproduction. A common question in botany is whether pollen can be classified as a haploid spore. To address this, it is essential to understand that spores are reproductive units produced by plants, fungi, and some other organisms, typically through asexual reproduction. In the life cycle of plants, spores are generally haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes. Pollen, being the male reproductive cell, is indeed haploid, as it develops from microspore mother cells through meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number by half. Therefore, pollen can accurately be described as a haploid spore, specifically a microspore, in the context of plant reproduction.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Pollen is a fine powdery substance produced by the male parts of seed plants, including flowering plants (angiosperms) and cone-bearing plants (gymnosperms). |

| Haploid Nature | Yes, pollen grains are haploid, meaning they contain half the number of chromosomes found in the parent plant. They are produced by meiosis in the anthers of flowers or microsporangia of cones. |

| Function | Pollen serves as the male gametophyte in seed plants, responsible for fertilization of the female ovule to form seeds. |

| Structure | Each pollen grain consists of a protective outer wall (exine and intine), cytoplasm, and a generative cell that divides to form two sperm cells in angiosperms, or a single sperm nucleus in gymnosperms. |

| Dispersal | Pollen is dispersed by wind, water, or animals (e.g., insects) to reach the female reproductive structures. |

| Allergenicity | Many pollen types are allergens, causing hay fever or allergic rhinitis in susceptible individuals. |

| Fossil Record | Pollen has a rich fossil record, used in palynology to study ancient plant life and climates. |

| Economic Importance | Pollen is essential for agriculture, as it facilitates the production of fruits and seeds in crops. |

What You'll Learn

- Pollen Structure and Function: Pollen grains contain male gametes, essential for plant reproduction, and are haploid cells

- Haploid vs. Diploid Spores: Pollen is haploid, formed via meiosis, unlike diploid spores in some plants

- Pollination Process: Pollen transfer enables fertilization, ensuring genetic diversity in seed-producing plants

- Life Cycle Role: Pollen is a key part of the alternation of generations in plants

- Comparison with Other Spores: Pollen differs from spores in fungi and ferns, which are often haploid dispersers

Pollen Structure and Function: Pollen grains contain male gametes, essential for plant reproduction, and are haploid cells

Pollen grains, often invisible to the naked eye, are microscopic powerhouses of plant reproduction. Each grain is a male gametophyte, a haploid cell containing the genetic material necessary to fertilize the female ovule. This haploid nature—derived from the Greek "haploos" meaning single—is critical, as it ensures genetic diversity through the fusion of two haploid cells (male and female) to form a diploid zygote. Without this mechanism, plants would lack the variability essential for adapting to changing environments.

Consider the structure of a pollen grain: it consists of a protective outer wall (exine and intine) and the male gametes within. The exine, often adorned with intricate patterns (e.g., spines or ridges), aids in species identification and facilitates adhesion to pollinators. For instance, smooth pollen grains are more likely to be wind-dispersed, while spiky ones adhere to insect bodies. This design is not arbitrary; it ensures efficient delivery to the stigma, the first step in fertilization. Practical tip: gardeners can enhance pollination by planting flowers with complementary pollen structures and bloom times.

The haploid nature of pollen is a biological marvel, but it also poses challenges. Haploid cells are more susceptible to environmental stressors like UV radiation and desiccation. To counteract this, plants invest in robust pollen walls and produce vast quantities of pollen—a single flower can release millions of grains. For example, wind-pollinated plants like grasses produce lighter, smoother pollen in higher volumes compared to insect-pollinated plants, which invest in larger, more ornate grains. This trade-off highlights the balance between efficiency and protection in pollen function.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the haploid state of pollen grains is a strategic adaptation. By halving the genetic material, plants reduce the energy required to produce reproductive cells while maximizing the potential for genetic recombination. This efficiency is particularly vital for species in resource-limited environments. For instance, desert plants often produce smaller, more resilient pollen grains to ensure reproduction despite harsh conditions. Understanding this can guide conservation efforts, such as selecting plant species with hardy pollen for reforestation projects.

In practical applications, the haploid nature of pollen is leveraged in plant breeding. Techniques like haploid induction, where plants are manipulated to produce haploid embryos, allow breeders to rapidly develop homozygous lines. This accelerates the creation of new crop varieties with desirable traits, such as drought resistance or higher yield. For home gardeners, selecting plants with known pollen viability (often indicated by vibrant flower colors) can improve garden health and productivity. In essence, pollen’s haploid structure is not just a biological curiosity but a cornerstone of plant survival and human innovation.

Effective Methods to Remove Mold Spores from Your Clothes Safely

You may want to see also

Haploid vs. Diploid Spores: Pollen is haploid, formed via meiosis, unlike diploid spores in some plants

Pollen grains, those microscopic carriers of plant fertility, are indeed haploid structures, a fact that sets them apart in the world of botany. This haploid nature is a direct consequence of their formation through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half. In contrast, some plants produce diploid spores, which retain the full set of chromosomes. Understanding this distinction is crucial for anyone delving into plant reproduction, as it highlights the diversity in how plants ensure their survival and propagation.

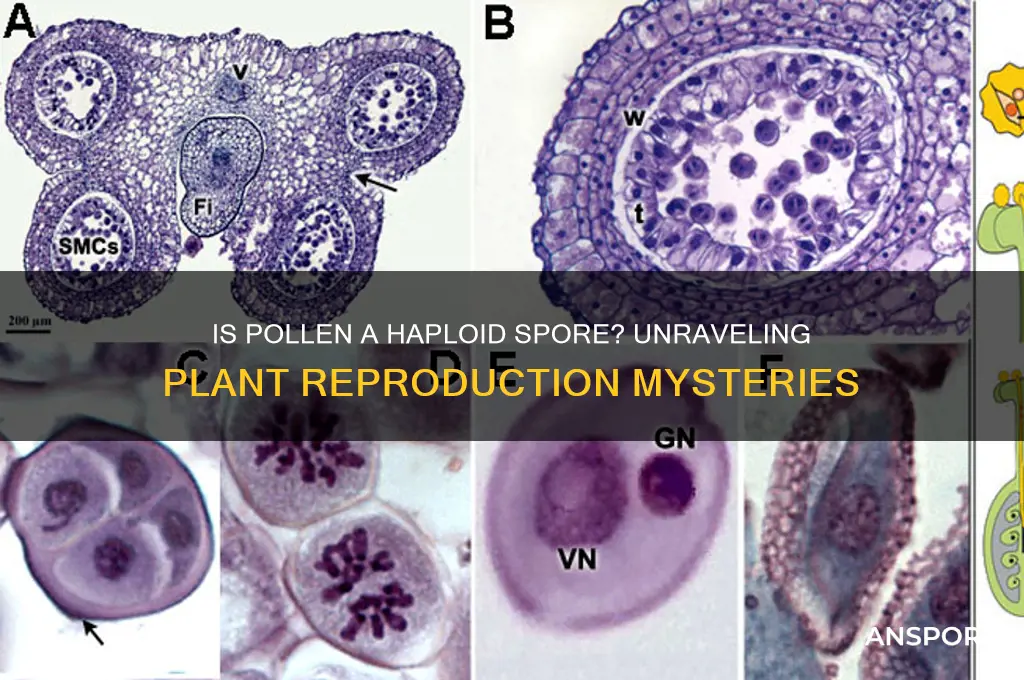

Consider the process of meiosis, a specialized cell division that occurs in the anthers of flowering plants. Here, diploid cells undergo two rounds of division, resulting in four haploid cells, each destined to become a pollen grain. This reduction in chromosome number is not arbitrary; it is a strategic move by plants to introduce genetic diversity. When a pollen grain fertilizes an egg, the resulting zygote is diploid, combining genetic material from both parents. This mechanism ensures that each new generation of plants has a unique genetic makeup, enhancing their ability to adapt to changing environments.

Diploid spores, on the other hand, are less common but equally fascinating. Found in certain groups of plants, such as ferns and some algae, these spores are produced without the reduction in chromosome number. Instead, they are formed through mitosis, a type of cell division that maintains the diploid state. This approach has its advantages, particularly in stable environments where genetic diversity may be less critical. For instance, ferns often thrive in shaded, moist habitats where their ability to reproduce quickly and efficiently is more important than genetic variation.

The practical implications of these differences are significant, especially in agriculture and horticulture. For example, understanding that pollen is haploid helps breeders predict and control genetic outcomes in hybridization programs. By selecting specific pollen donors, breeders can introduce desirable traits into new plant varieties, a technique widely used in crop improvement. Conversely, knowledge of diploid spores can aid in the cultivation of ferns and other spore-producing plants, where maintaining genetic consistency may be a priority.

In conclusion, the distinction between haploid and diploid spores is a fundamental aspect of plant biology, with far-reaching implications for both natural ecosystems and human endeavors. Pollen’s haploid nature, a result of meiotic division, ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, while diploid spores offer stability and rapid reproduction in certain plant groups. By grasping these concepts, one can better appreciate the intricate strategies plants employ to thrive and evolve. Whether you’re a botanist, a gardener, or simply curious about the natural world, this knowledge provides valuable insights into the mechanisms that drive plant life.

Does Black Mold Release Spores into the Air? Understanding the Risks

You may want to see also

Pollination Process: Pollen transfer enables fertilization, ensuring genetic diversity in seed-producing plants

Pollen, a fine powdery substance produced by the male parts of seed-bearing plants, plays a pivotal role in the reproductive cycle of angiosperms and gymnosperms. It is, indeed, a haploid spore, carrying half the genetic material of the parent plant. This haploid nature is crucial for the pollination process, which facilitates fertilization and ensures genetic diversity in offspring. When pollen is transferred from the anther (male reproductive organ) to the stigma (female receptive part), it germinates, forming a pollen tube that delivers sperm cells to the ovule. This intricate journey is the foundation of sexual reproduction in plants, blending genetic material from two parents to create seeds with unique traits.

Consider the mechanics of pollen transfer, a process both delicate and diverse. Pollination can occur via abiotic agents like wind and water or biotic agents such as insects, birds, and bats. For instance, wind-pollinated plants like grasses and pines produce lightweight, dry pollen in large quantities to increase the likelihood of reaching distant stigmas. In contrast, insect-pollinated plants like orchids and sunflowers invest in colorful petals, nectar, and scented fragrances to attract pollinators. Each method is tailored to the plant’s environment, maximizing efficiency while minimizing energy expenditure. Understanding these mechanisms highlights the adaptability of plants in ensuring successful fertilization.

The genetic diversity resulting from pollination is essential for plant survival and evolution. When pollen from one plant fertilizes the ovule of another, the offspring inherit a combination of traits from both parents. This genetic recombination allows plant populations to adapt to changing environments, resist diseases, and thrive in diverse ecosystems. For example, in agricultural settings, cross-pollination between crop varieties can lead to hardier, more productive plants. However, this process is fragile; habitat destruction, pesticide use, and climate change threaten pollinators, jeopardizing the genetic diversity that sustains ecosystems and food systems alike.

Practical steps can be taken to support pollination and preserve genetic diversity. Home gardeners can plant a variety of flowering species to attract pollinators, avoiding pesticides that harm bees and butterflies. Farmers can adopt crop rotation and intercropping techniques to enhance natural pollination. On a larger scale, conservation efforts must focus on protecting pollinator habitats, such as meadows and forests, and promoting sustainable agricultural practices. By safeguarding the pollination process, we ensure the resilience of plant species and the stability of ecosystems that depend on them.

In conclusion, the pollination process, driven by the transfer of haploid pollen, is a cornerstone of plant reproduction and genetic diversity. From the microscopic journey of pollen grains to the macroscopic impact on ecosystems, this process underscores the interconnectedness of life. By appreciating its complexity and vulnerability, we can take informed actions to protect it, ensuring a biodiverse and sustainable future for generations to come.

Can Bleach Kill Spores? Uncovering the Truth About Disinfection

You may want to see also

Life Cycle Role: Pollen is a key part of the alternation of generations in plants

Pollen, often seen as mere allergens or plant dust, plays a pivotal role in the alternation of generations, a fundamental life cycle process in plants. This cycle involves the alternation between a diploid sporophyte generation and a haploid gametophyte generation. Pollen, being a male gametophyte, is indeed a haploid spore, carrying half the genetic material of the parent plant. This haploid nature is crucial for genetic diversity, as it allows for the recombination of traits when pollen fertilizes the female gametophyte, or embryo sac.

To understand pollen’s role, consider the steps of its journey. First, it is produced within the anther of a flower, where microspores undergo meiosis to become haploid. These microspores develop into pollen grains, each containing a generative cell that will divide to form two sperm cells. When pollen lands on the stigma of a compatible flower, it germinates, growing a pollen tube that carries the sperm to the ovule. This process, known as double fertilization in angiosperms, results in the formation of a diploid zygote (future embryo) and a triploid endosperm, ensuring the next generation’s survival.

From a practical standpoint, gardeners and farmers can leverage this knowledge to improve plant breeding. For instance, hand-pollination or controlled pollination techniques can be employed to ensure cross-fertilization between desired plant varieties. This is particularly useful in crops like corn or apples, where specific traits (e.g., disease resistance or fruit size) are sought. Timing is critical: pollen viability typically lasts 24–48 hours, so pollination must occur during the flower’s receptive period. For indoor plants, using a small brush to transfer pollen can mimic natural processes, increasing fruit set and seed production.

Comparatively, pollen’s role in the alternation of generations contrasts with that of spores in ferns or mosses, where the gametophyte generation is dominant and free-living. In flowering plants, the gametophyte (pollen and embryo sac) is highly reduced, relying on the sporophyte for nutrition and support. This evolutionary adaptation allows angiosperms to allocate more resources to growth and reproduction, contributing to their success as the most diverse group of land plants.

In conclusion, pollen’s status as a haploid spore is not just a biological curiosity but a cornerstone of plant reproduction. Its role in the alternation of generations ensures genetic diversity, supports ecosystem stability, and provides practical applications for agriculture and horticulture. By understanding this process, we can better appreciate the intricate balance of nature and harness it for sustainable plant cultivation.

Is Buying Shroom Spores Legal? Understanding the Laws and Risks

You may want to see also

Comparison with Other Spores: Pollen differs from spores in fungi and ferns, which are often haploid dispersers

Pollen, often mistaken for a typical spore, diverges significantly from the spores of fungi and ferns in its role and life cycle. While both pollen and these other spores are haploid—carrying a single set of chromosomes—their functions and dispersal mechanisms are distinct. Fungal spores, for instance, are primarily agents of asexual reproduction, dispersing to colonize new environments. Fern spores, similarly, are haploid dispersers that develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes. Pollen, however, serves a unique purpose in seed plants: it is a male gametophyte that travels to the female reproductive structure to fertilize the egg, a process integral to sexual reproduction in angiosperms and gymnosperms.

To understand this difference, consider the journey of a pollen grain versus a fern spore. A fern spore lands on a suitable substrate, grows into a small, heart-shaped gametophyte, and produces sperm that requires water to reach the egg. In contrast, pollen grains are transported by wind, insects, or other vectors directly to the stigma of a flower or cone, where they germinate and form a pollen tube to deliver sperm cells. This direct, targeted approach highlights pollen’s specialized role in fertilization, setting it apart from the more generalized dispersal strategies of fungal and fern spores.

From a practical standpoint, this distinction has implications for agriculture and ecology. Farmers and gardeners must consider pollen’s specific dispersal needs—such as attracting pollinators or ensuring wind flow—to optimize plant reproduction. For example, apple orchards rely on bees to transfer pollen between flowers, while grasses depend on wind dispersal. In contrast, managing fungal or fern spore dispersal often involves controlling moisture levels or physical barriers to prevent unwanted colonization. Understanding these differences allows for more effective strategies in both cultivation and conservation efforts.

A persuasive argument can be made for the evolutionary sophistication of pollen compared to other spores. While fungal and fern spores are successful in their roles, pollen’s integration into the complex reproductive systems of flowering plants has enabled the diversification and dominance of angiosperms in terrestrial ecosystems. This specialization reflects a higher level of adaptation, where pollen’s function is not just survival but also the facilitation of genetic diversity through sexual reproduction. Such a comparison underscores the unique evolutionary trajectory of seed plants and their reliance on pollen as a key reproductive agent.

In conclusion, while pollen shares the haploid nature of fungal and fern spores, its role as a male gametophyte in sexual reproduction distinguishes it fundamentally. This comparison reveals not only the diversity of spore functions in the plant and fungal kingdoms but also the specialized adaptations that have driven the success of seed plants. Whether in the context of biology, agriculture, or ecology, recognizing these differences is essential for appreciating the intricate mechanisms that sustain life on Earth.

Mastering Spore: A Guide to Checking Badges in the Game

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, pollen is a haploid spore produced by the male part of seed plants, such as flowering plants (angiosperms) and conifers (gymnosperms).

Pollen is considered a haploid spore because it develops from a microspore mother cell that undergoes meiosis, reducing its chromosome number by half, resulting in a haploid (n) cell.

Pollen is a haploid spore (n), while diploid spores are formed from diploid cells (2n) and are not involved in the reproductive process of seed plants. Diploid spores are more commonly found in ferns and other non-seed plants.

Yes, pollen directly participates in fertilization. After landing on the stigma of a flower, the pollen grain germinates, producing a pollen tube that delivers the haploid male gamete to the ovule, where it fuses with the haploid female gamete to form a diploid zygote.